Paris is generally a great city for readers of comic strips, or what the French call bandes dessinées. But this spring, the City of Lights truly outdid itself, offering major museum retrospectives of the careers of two great American cartoonists: Art Spiegelman, at the Centre Georges Pompidou; and R. Crumb, at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Crammed into a maze of corridors in the first case, and sprawling through half a dozen high-ceilinged galleries in the second, these shows display comics as if they were sacred texts, with every page of Crumb’s Genesis and Spiegelman’s Maus arrayed sequentially on the walls like salvaged scraps of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

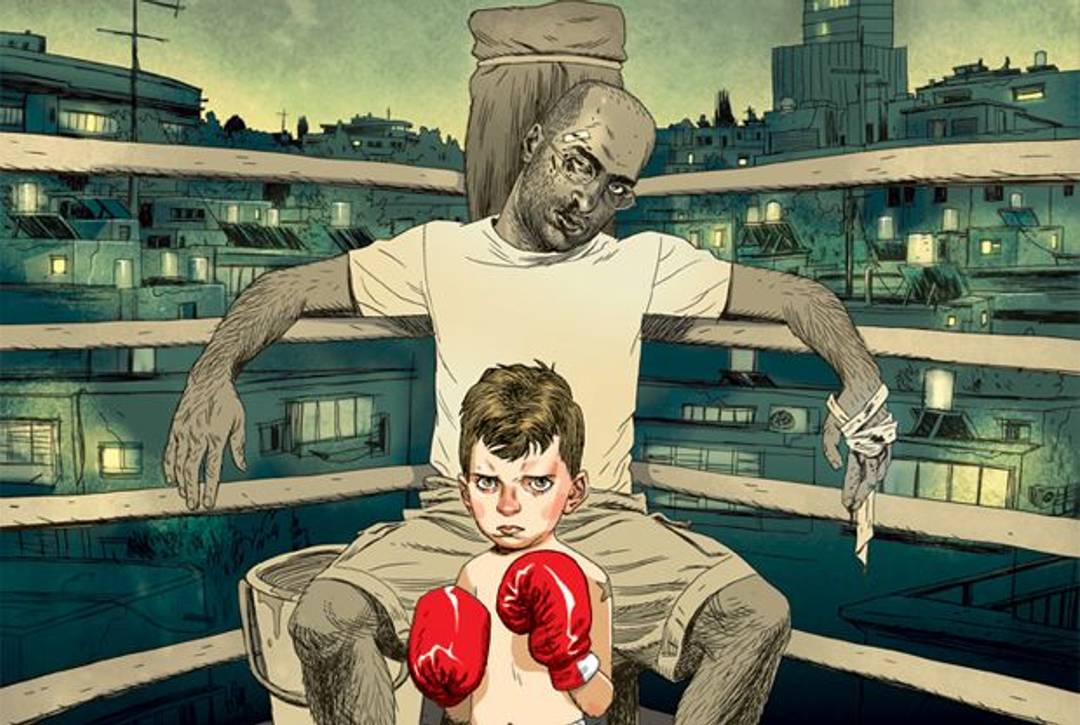

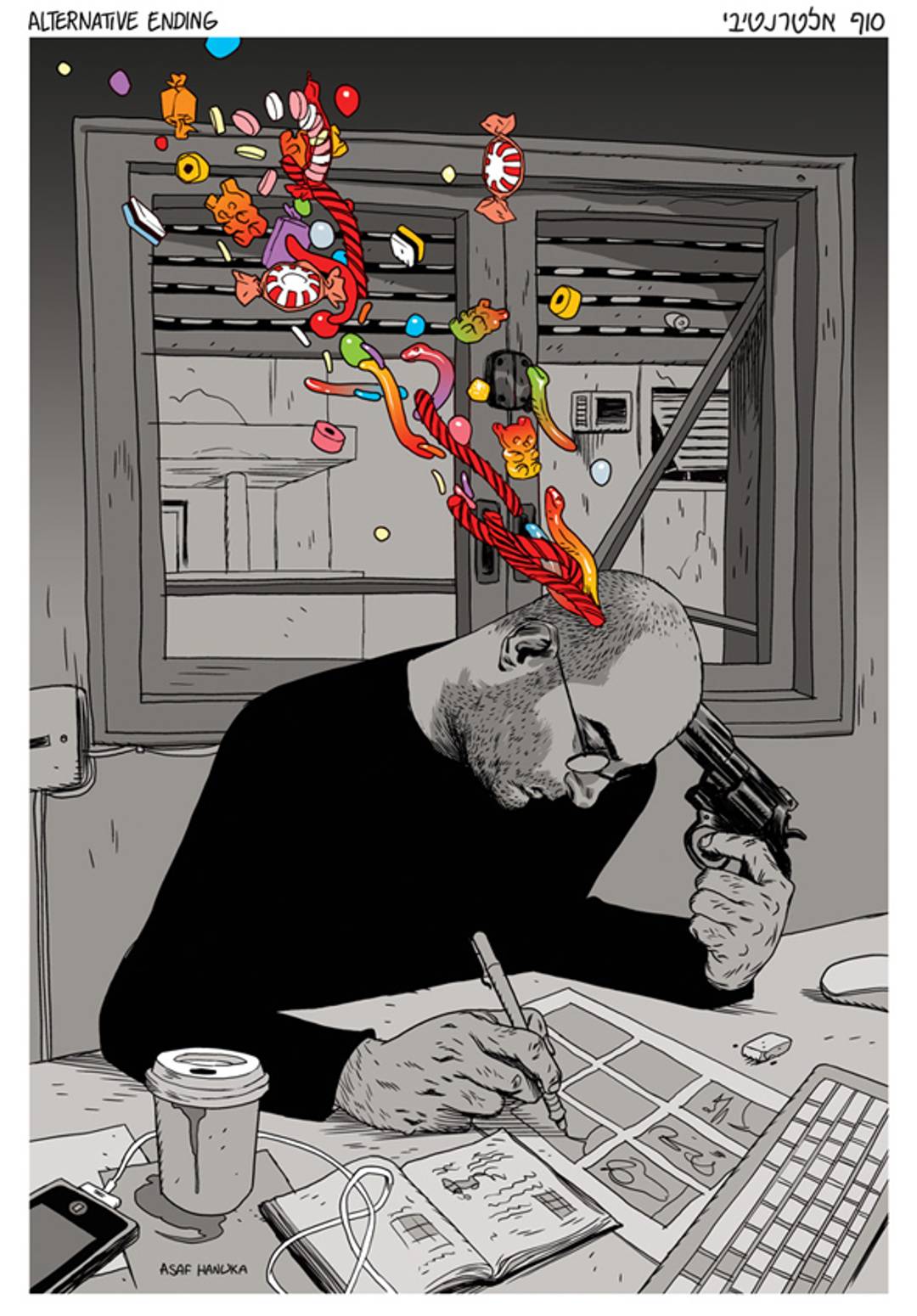

But another, much more modest—and more portable—retrospective has been on display on the shelves of Parisian comic-book shops since the beginning of June. It consists of a slim hardcover album that collects two years’ worth of Asaf Hanuka’s brilliant weekly comic strip, The Realist, which until now has been published in an Israeli newspaper and online in Hebrew and English. Now in French, it has been presented as a book for the first time, under the title K.O. à Tel Aviv, which is a more literal description of the strip’s contents than The Realist. “K.O.” of course means “knock-out”—and the cover of the book reprints one of Hanuka’s most striking images: a rendering of himself, bruised and bloodied, while his young son, outfitted in boxing gear, scowls in a fighting stance.

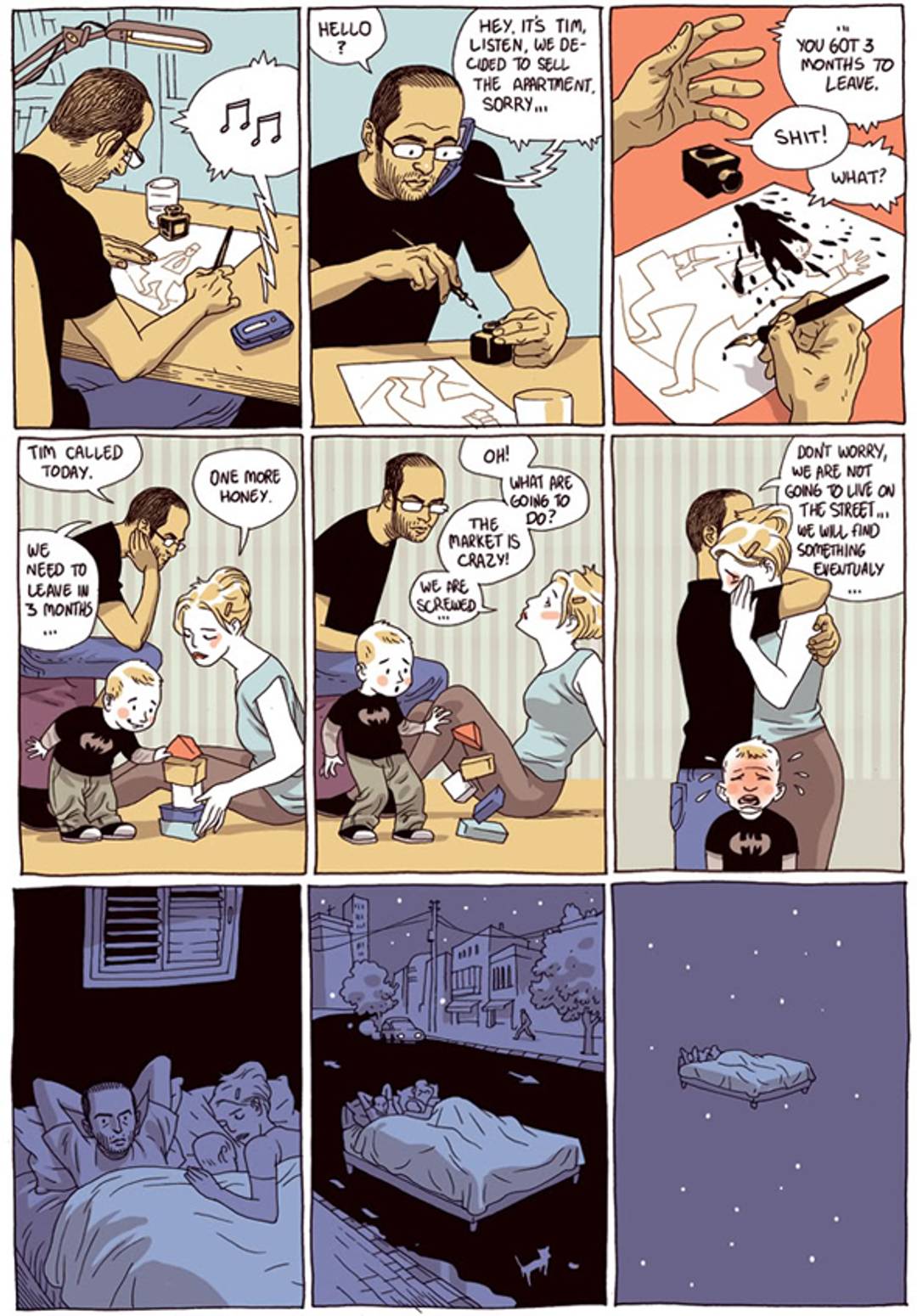

In French, aloud, K.O. also sounds like “chaos,” which is what the strip is about. It began in 2010 when the newspaper The Calcalist asked Hanuka, by then well known in Israel as a commercial illustrator and as a contributor to the animated film Waltz With Bashir, for a weekly back-page contribution. Since it was a business paper asking, Hanuka decided he might as well focus on his real-life real-estate woes. The first of the autobiographical strips, published on Feb. 1, 2010, has Hanuka discovering that he and his wife and their young son need to find a new place to live, immediately and in a “crazy” market, because the apartment they’ve been renting has been sold.

It’s clear from that first strip that Hanuka’s goal was not financial reportage—or, for that matter, simple realism of any sort. As a kid, he shared an “imaginary world” with his twin brother, Tomer, who is now an award-winning illustrator and comics artist living in New York. “We both drew all the time, we were completely into American comics, and we invented stories,” Asaf told Tablet recently, in an old-fashioned bistro in the 11th arrondissement. “It was the thing we did together.”

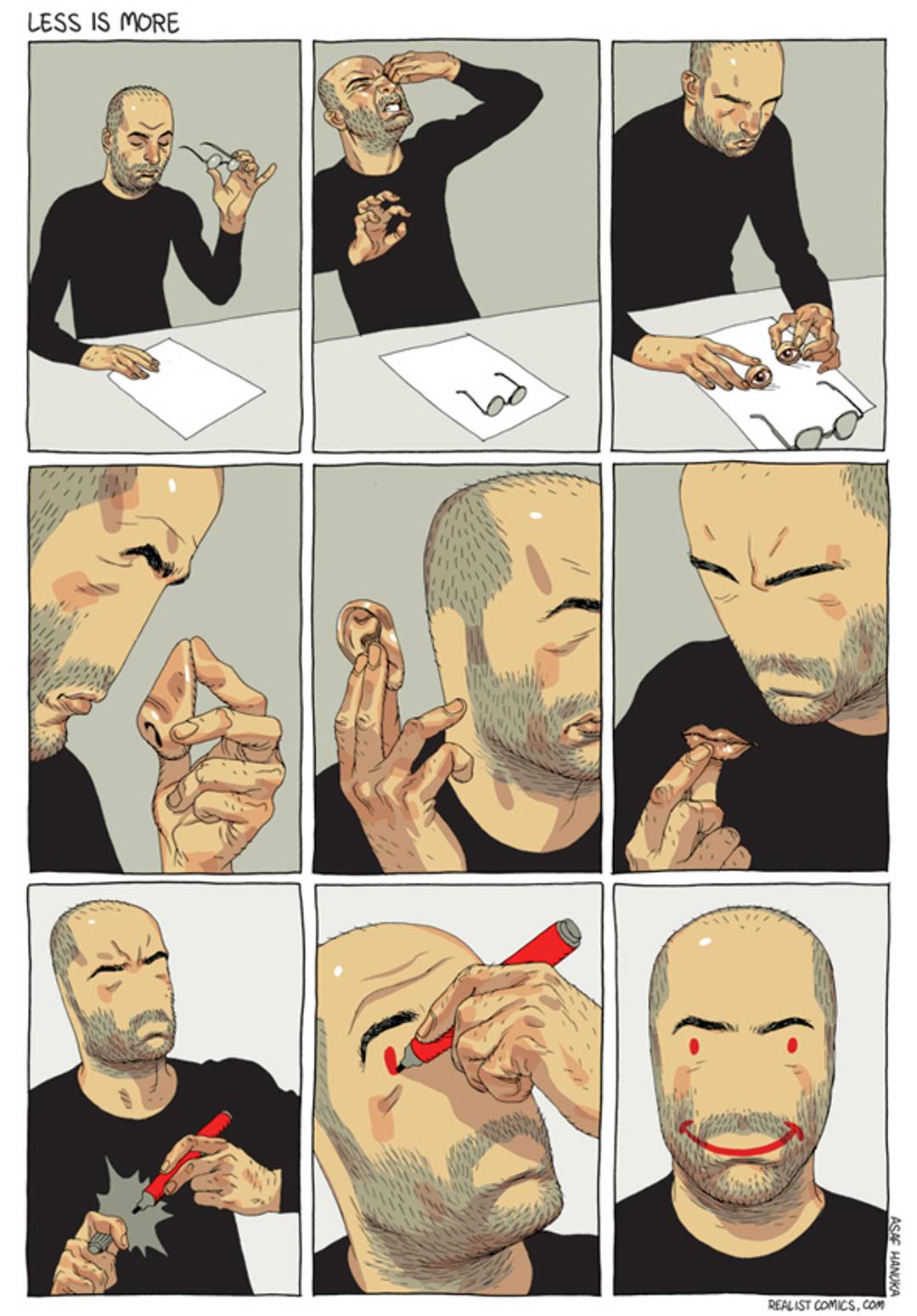

While on the staff of an Israeli army newspaper, Asaf began to create graphic adaptations of Etgar Keret’s stories, which led to the collaborative Keret/Hanuka graphic novel Pizzeria Kamikaze. The first Realist strip, about Hanuka’s housing worries, ends not with a punchline but with a dreamlike image, the kind of thing Etgar Keret specializes in: The family’s bed appears first in the street, and then in a starry sky. What he aims to producenow is not memoir, he says, but “emotional autobiography.” It’s a “weekly exercise,” as he calls it, in which he takes the most emotionally intense experience he’s had and uses the bag of tricks he’s developed in two decades as a commercial artist to create striking images: “The thing is never to lie, always do the thing that burns the most that week.”

The results can be amusing, at times bewildering, and also as emotionally resonant as the most brilliantly terse poetry. Sometimes he relies on archetypes of the genre: In one strip, he represents himself as each member of the Fantastic Four to reflect on the distinct emotional roles he plays in his son’s life; and in another, when a therapist draws out his anger, he transforms very briefly into the Incredible Hulk. One strip has Hanuka and his wife, in boxing gear, beating the living hell out of each other, until the final panel shows them, back in reality, going to sleep mad, on opposite sides of the bed. Hanuka recalls that when he published it, his mother phoned him to ask whether he would be getting a divorce. “You have to read next week,” he told her. “Keep following the blog and you’ll know. I don’t know. I don’t know the future. I’m just reporting the present.”

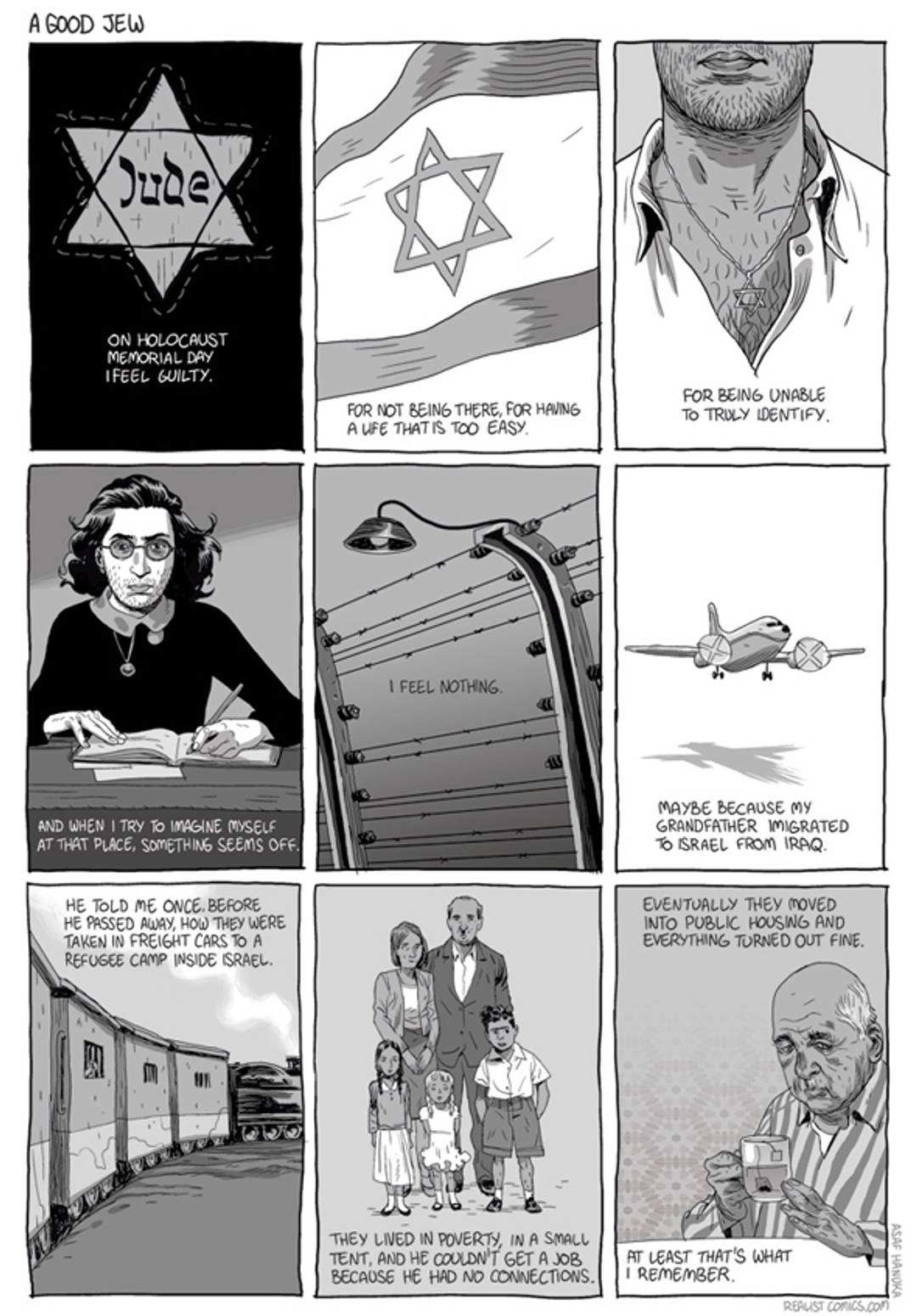

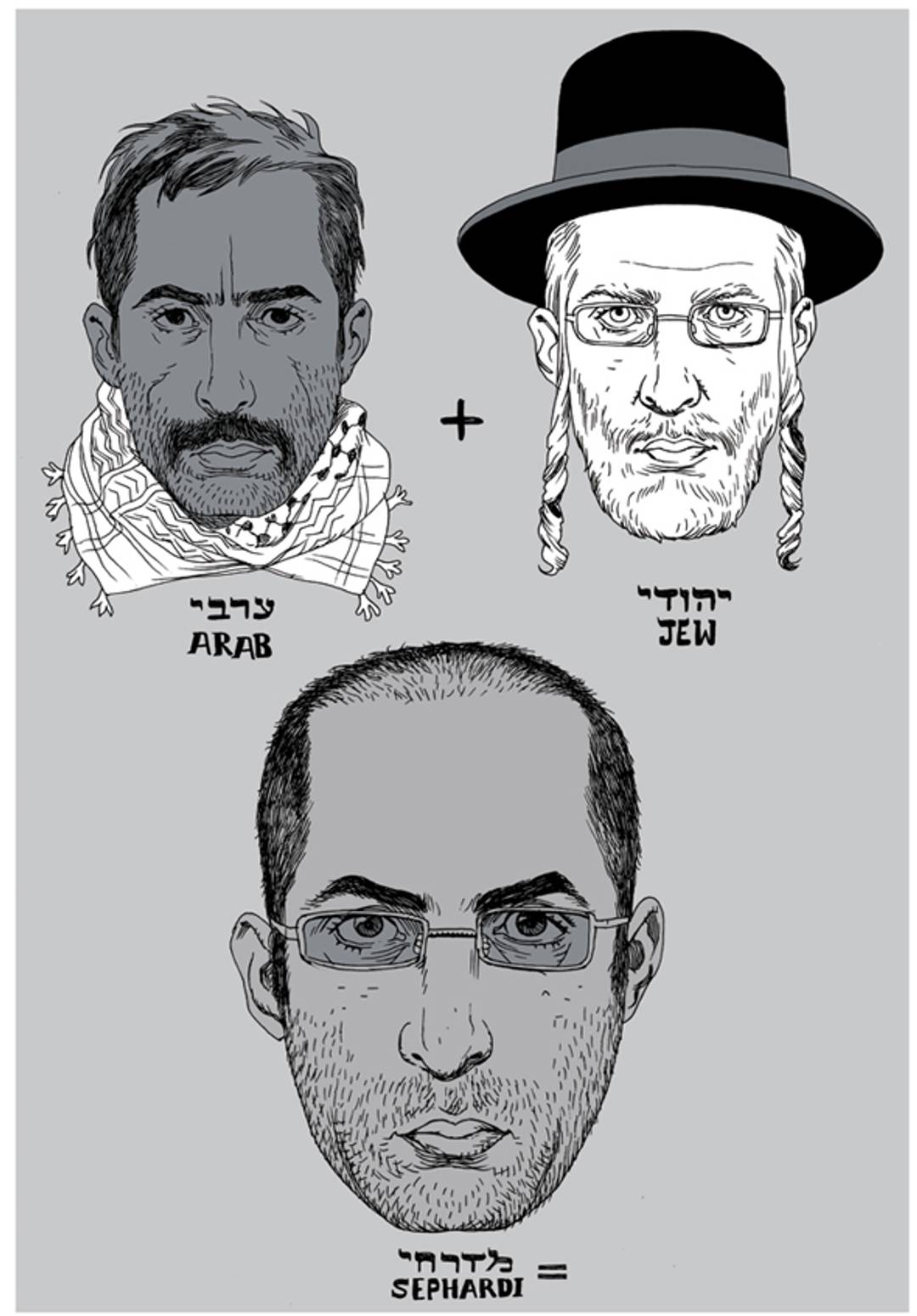

Hanuka can be equally unsparing in his musings on Jewish identity, which are often informed by his experience as a Mizrahi Israeli. In explaining why Holocaust Memorial Day doesn’t move him, he draws himself, in one panel, as a bestubbled Anne Frank, emphasizing how little he has in common with the Dutch teenager; he also explains that when his grandfather arrived in Israel from his native Iraq, he was “taken in freight cars to a refugee camp.” That’s why, Hanuka implies, he’s “unable to truly identify” with the tragedy being memorialized. In another strip, he draws three pseudo-self-portraits—the captions read, simply, “Arab + Jew = Mizrahi”—in a style reminiscent of old racist caricatures such as those that used to appear in Punch.

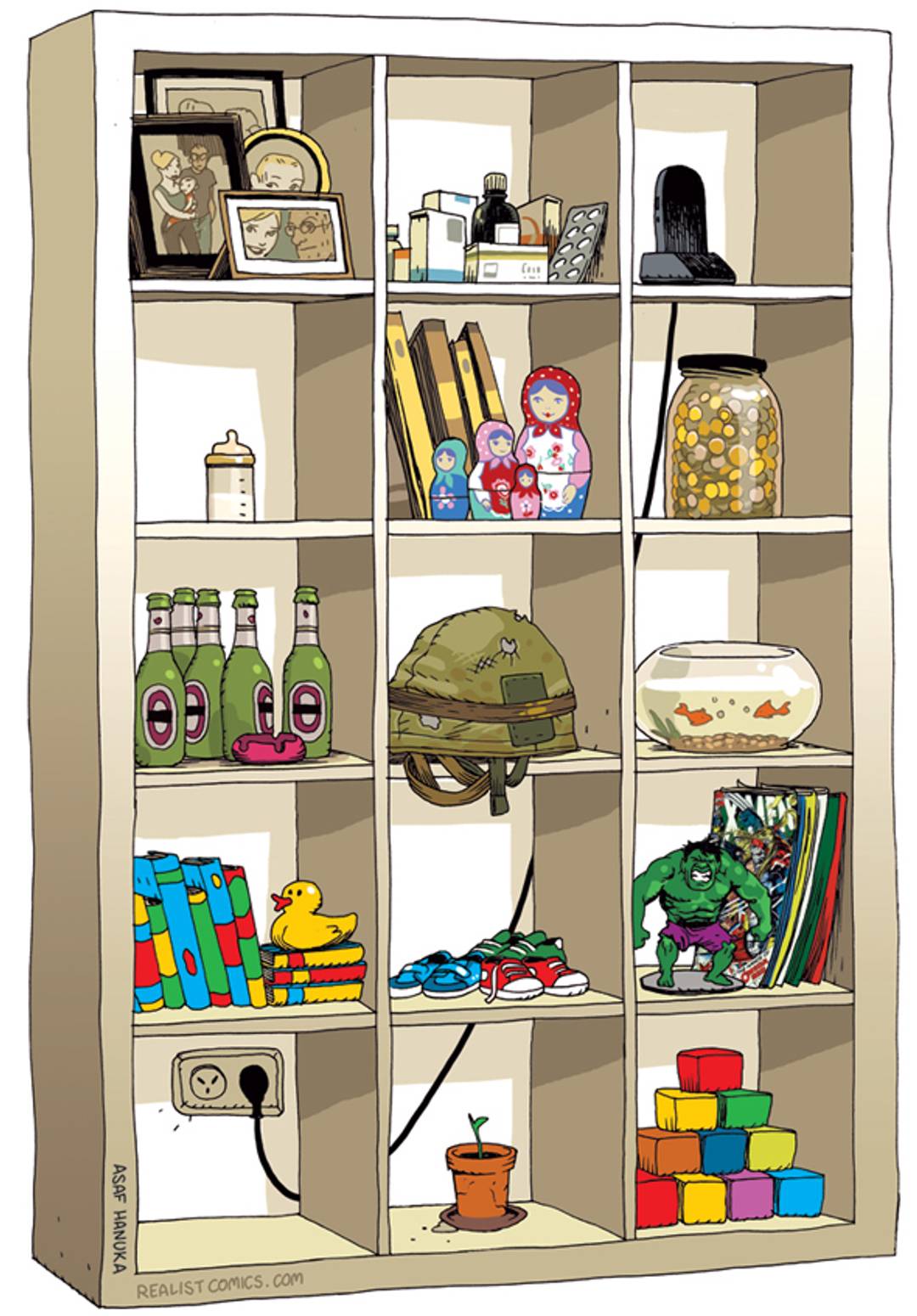

The goal of all this is, of course, to provoke—just as in Crumb’s and Spiegelman’s finest work—and also to give form to the artist’s intense, if inchoate, ideas and feelings. Indeed, one way of understanding The Realist is as Hanuka’s aestheticized version of the talking cure—a weekly attempt to impose order onto the mess of his life by rendering it into words and pictures and constraining it into a set of little boxes. (Sometimes he does this literally, as in the single-panel strip where he shoehorns his major life experiences into the 15 frames of an IKEA Expedit bookshelf.) Hanuka says he’s been to therapy alone and with his wife—his mother is a marriage counselor herself—but that drawing the Realist is, for him, “much better than therapy. Much better.”

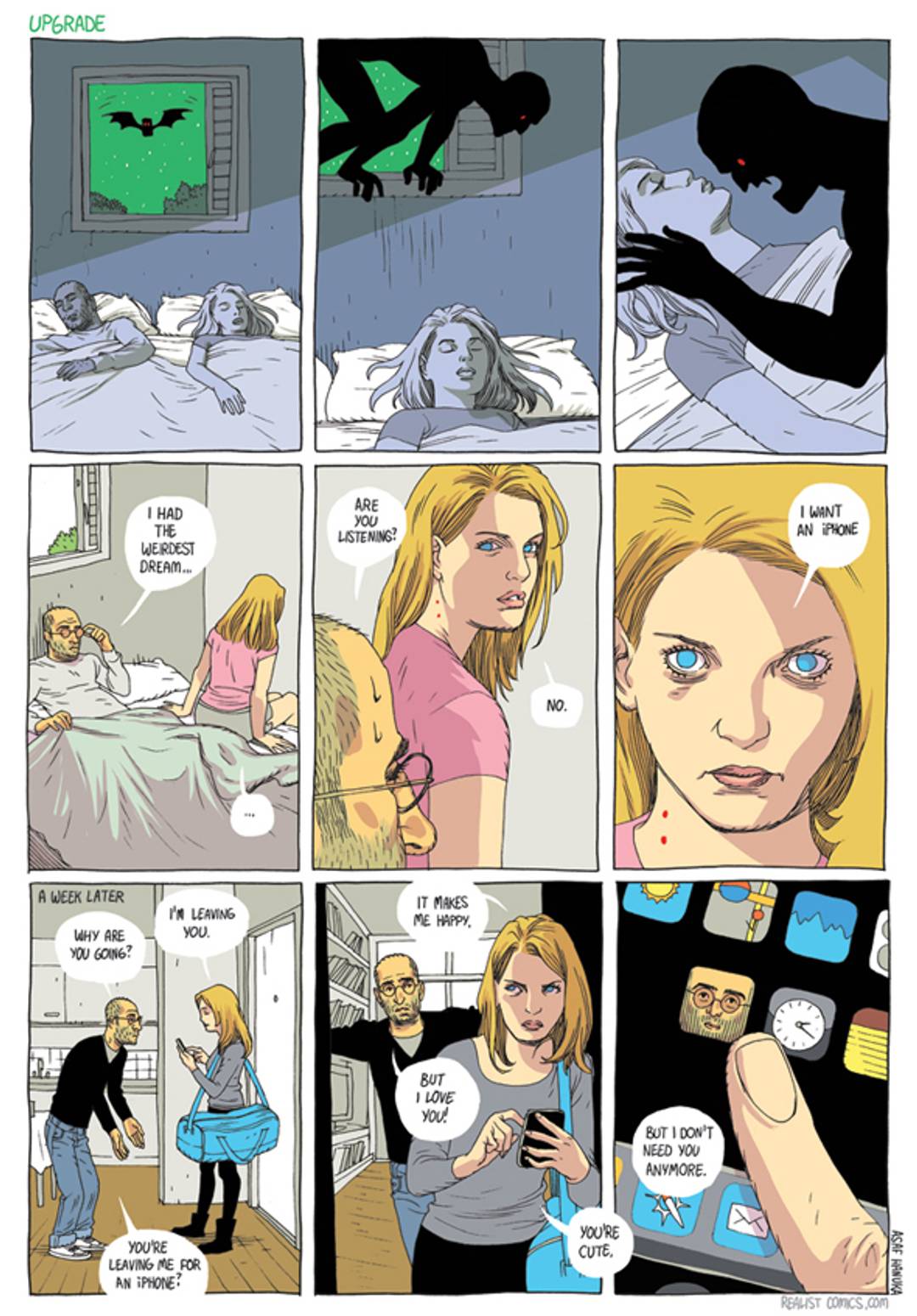

Hanuka’s subjects change unpredictably from week to week. He captures what it feels like to be living with someone who just got her first iPhone, or to obsess about one’s self-presentation on Facebook. He offers brilliant, wordless emotional abstractions, too. In his reflections on the Tel Aviv tent protests, the flotilla fiasco, and the imprisonment of Gilad Shalit, he responds to news events not as politics but as part of his daily life.

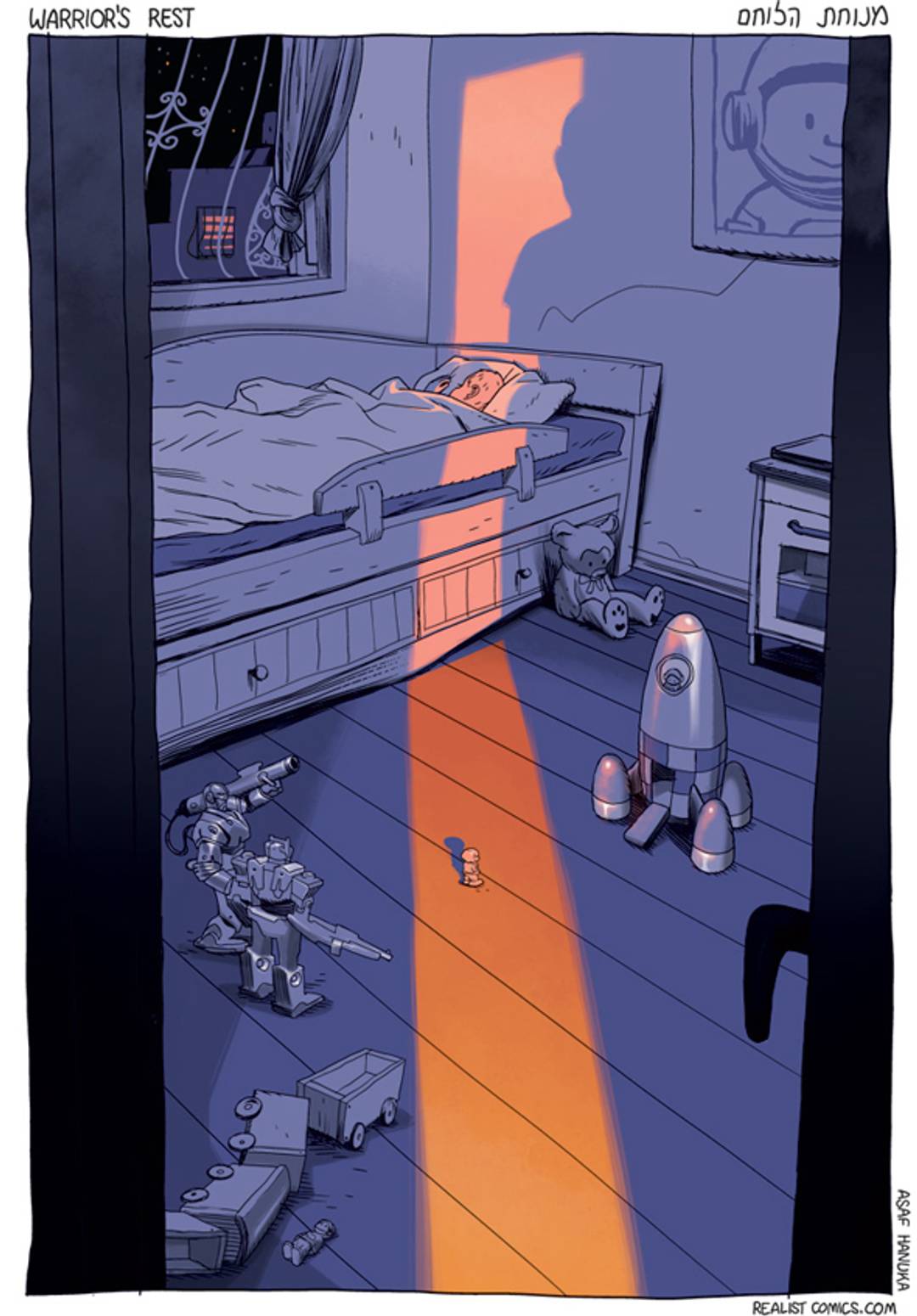

In fact, because the strip occasionally comments on current headlines, a newspaper or blog seems a better venue for it than a book. The French editors didn’t seem to know what to explain and what to leave implicit; they provide Wikipediaesque marginal glosses on “Purim” and “Kiddush,” but most French readers would have no way of knowing that the strip depicting Hanuka’s son, peaceful in his bed, was a heartbreaking reflection on Gilad Shalit’s release. So, as welcome as the French album is—it presents Hanuka’s work gorgeously and stakes a claim for him in one of the world’s most supportive markets for storytelling in this medium—the crucial experience of The Realist remains the serial one. Whereas wandering around the Crumb and Spiegelman retrospectives gives one a sense of the vast possibilities of the comic strip, reading Hanuka each week one can glimpse the vitality of the form in real time.

Josh Lambert (@joshnlambert), a Tablet Magazine contributing editor and comedy columnist, is the academic director of the Yiddish Book Center, Visiting Assistant Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and author most recently ofUnclean Lips: Obscenity, Jews, and American Culture.