What the Dead Have To Say to Us

Yale’s pioneering archive of Shoah testimonies reshaped the way tragedies are remembered. But are we listening?

In the spring of 1979, Dori Laub, a Yale psychiatrist and child survivor of the Holocaust, and Laurel Vlock, a dynamic New Haven radio and TV interviewer, met with four survivors who had volunteered to answer questions about their experiences. The interviews were recorded on videotape, at a time when it was more common to record on audiotape; unexpectedly, the session lasted past midnight. The expressive clarity and power of the testimonies led to the founding of the Holocaust Survivors Film Project (HSFP), which, after little more than a year of taping, collected 183 testimonies. Recorded chiefly but not exclusively in New Haven, those tapes became the nucleus of Yale’s “Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies”—now the Fortunoff Archive—which was inaugurated on Nov. 15, 1982, thanks to a grant from the Charles Revson Foundation for the purpose of taping more such interviews and making the results nationally accessible. In the 30 years since, the Yale project—the archive itself, and the way the interviews were conducted and distributed—has reshaped the way that the Holocaust and other historical tragedies are remembered. When Steven Spielberg launched his Survivors of the Shoah Visual History project some 11 years later, he mainly followed Yale’s pattern of sympathetic interviewing and interview training, though on a much larger scale.

Most Holocaust research immediately after the liberation of the concentration camps centered on the perpetrators: to identify, find, and prosecute them; also to help historians trace the evolution of the Shoah. But the survivors who played an essential role in providing this evidence were seldom asked about their present lives or concerns relevant to rebuilding families and communities. The one major exception was David Boder, a psychology professor who interviewed in 1946 over 100 Jewish and non-Jewish survivors in European displaced-persons camps. His work, however, remained largely unknown because he published only eight translated excerpts of his interviews in 1949 with the title I Did Not Interview the Dead. In 1961, the Eichmann trial brought the personal experiences of survivors to the fore. Radio-broadcast in its entirety, with over 100 witnesses testifying, the interviews allow the survivors’ distinctive voices and personalities to break through. They were viewed as individuals again, rescued, as Haim Gouri remarked in his account of the trial, Facing the Glass Booth, “from the danger of … being perceived as all alike, all shrouded in the same immense anonymity.”

The Fortunoff Archive recast Holocaust survivor testimony as an extra-juridical genre—an oral and populist form of expression that opened the way for survivors or other eyewitnesses to tell what they knew. In doing so, the archive and its dedicated collaborators have done more than contribute to Holocaust studies. They also helped to expand the concept and appreciation of oral history, of memory and trauma studies, and what has recently been named “media witnessing.”

Many assumed that with the passing of the years the memory of the Holocaust would fade, and some even criticized giving so much emphasis to it, considering it an exploitative, political component of Jewish suffering as well as a displacement of true Jewish learning. I would argue that Holocaust studies as a whole have helped to create a cadre of thinkers and scholars who do more than detail Jewish suffering; they are memory activists who show how important it is to keep alive a many-sided culture of remembrance and preserve it against terrible political simplifications. We have realized, I think, that there is always enough human suffering and anguish to go around. Scapegoating, homophobia, racism, and a vicious state-supported propaganda can target any community; we know enough about Hitler’s postwar plans to surmise that these included, if not further exterminations of particular ethnic or faith communities, then their enslavement.

***

As the figure of the survivor moved deeper into the public consciousness, a remarkable multinational assemblage of scholars, young and old, was recruited to participate in Yale’s memory work. Setting up, with Yale’s help, pioneering affiliates, not only in the United States, but also in England, Israel, France, Belgium, Germany, Slovakia, and Yugoslavia, and testing the medium of videotape together with an interviewing protocol that cedes more of the initiative to the survivor, each Yale-affiliated group keeps a copy of the testimonies it records and sends another copy to Yale to be preserved and catalogued. Since 1984, bibliographic records for the Yale testimonies—which now number over 4,500—have been available online, providing intellectual access to the collection. But to view the testimonies themselves it was necessary to visit Yale. Because of the technical advance of digital formats and the obsolescence of analog broadcasting, Yale is also in the process of digitizing all its testimonies, a process that will be complete in 2014, at which point remote access to the Yale tapes will be available at other universities and institutions.

Such technical progress, however, important as it is, does not help us meet a major testimonial challenge, by which I mean the willingness to listen, which requires moral engagement. For little in the tapes is comforting—mainly, the courage of the victims in telling, and so, to an extent, reliving their story. Arthur Frank writes in The Wounded Storyteller (1995): “One of the most difficult duties is to listen to the voices that suffer.” That suffering persists, since terrifying memories never entirely subside. Moreover, if to listen to the witness is to become a witness oneself, since the evidence, even at the distance of so many years, is overwhelming (consider only the recent discovery of mass graves in Ukraine), the empathic powers of those who were not there come under severe pressure.

Today survivor testimony is almost exclusively video testimony. Even if this change seems like a minor one (in sync with that from radio to TV and Internet), what matters is the act of witnessing in the communicative context of the electronic media: The visibility bestowed by video ensures the formal “audiencing” of the survivors and consolidates a larger move by them into the public consciousness. Yet testimony at this point also makes us more aware of the interviewer. By 1980 the survivor interviews are no longer standard debriefings, as in the immediate postwar years. They now serve principally both present and past: the present, by assisting the witnesses to retrieve and deal with memories that still burden, consciously or unconsciously, family life; the past, in that guarantees are needed, as the eyewitness generation passes from the scene, that what they endured will not be forgotten. “The mission that has devolved to testimony,” according to Annette Wieviorka (a major French historian who coordinated Yale’s taping in France ), “is no longer to bear witness to inadequately known events but rather to keep them before our eyes. Testimony is to be a means of transmission to future generations.”

This does not mean, of course, that this mission/transmission is without problems. Much has been written about secondary trauma: that is, how some of the effects of trauma suffered by the parents in the Holocaust were involuntarily transferred to the children of their new, post-Holocaust families. (To try and ignore this psychoanalytic issue is a bit like ignoring climate change.) But to give a more common and poignant example of what Wieviorka means by keeping the events, now mainly (if still not quite adequately) known, before our eyes, let me instance an episode from one of the earliest of the Yale tapes in which a survivor describes an incident in Poland during a deportation. When the survivor’s grandmother, an old woman with a broken leg not quite healed, tries to climb into a cart but is too weak to do it by herself, asks in Polish for help, a German soldier nearby says, “Yes, I’ll help you,” takes a gun from his holster, and kills her.

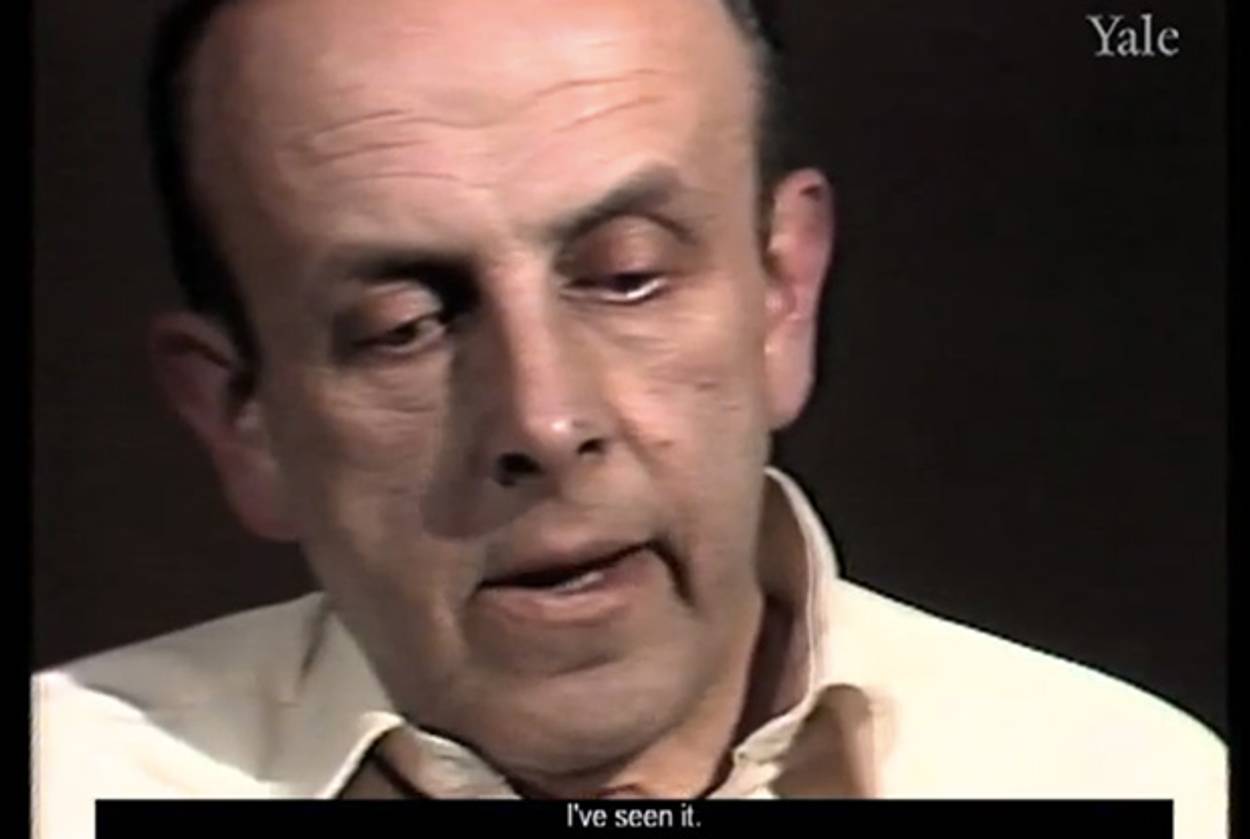

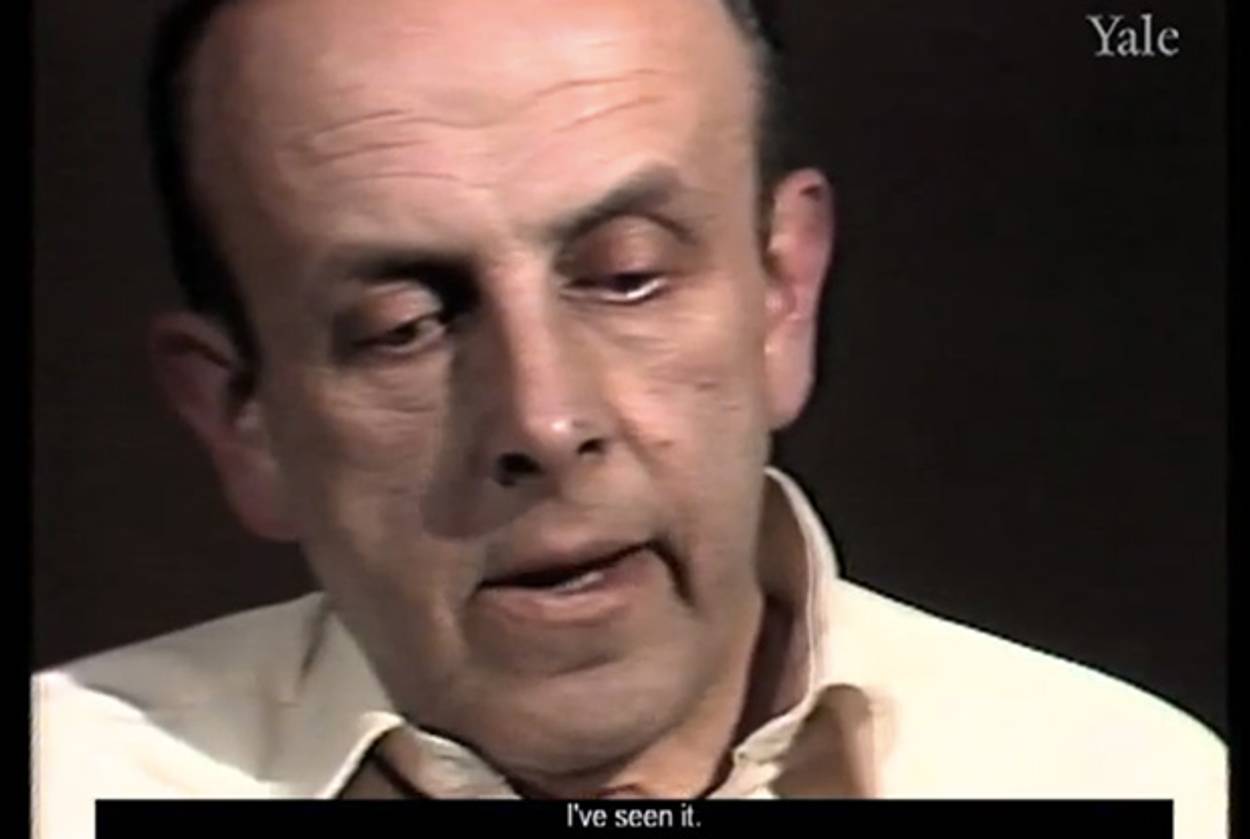

Her grandson, describing this episode, breaks down. He cries, or rather tries not to, contorting his face in a painful, gnawing motion that forces out the words “I’ve seen it.” When he is calm again, one of the interviewers asks him, very hesitantly, whether he could tell what moved him most (or what made him cry at this point in the interview) and whether he had also cried at the time it happened.

The two conjoined questions, though they seem intrusive at first, are, important. The answer to the second question is that he did not cry then, because he was “petrified.” The answer to the first is also simple but strikes me as wonderfully strong, because it comes so close to the agony that preceded it. He cried now because of “the inhumanity: someone asks for help, and that help is expressed as a killing action.”

Leon S. Edited Testimony (HVT-8025): The scene described runs from 3m20–7m20:

Yale’s interviewing protocol calls for not pressuring the survivor/witness and even for giving the initiative to the witness. This stance goes together with other practices, e.g., the testimonies do not show the interviewers on-screen, so that everything remains oriented toward the presence of the witness. All-in-all, survivor and interviewer enter a “testimonial alliance” in which the interlocutor becomes more a partner or exegete than a challenger. All this should go to restore the survivor’s self-image, so relentlessly and systematically debased by the perpetrators. In his near-Manichean poem “Testimony,” Dan Pagis writes that compared to the contemptuous stance of the Nazi Camp’s elegantly outfitted, all-powerful guards “I was a shade./ A different Creator made me.”

The testimonies expect the survivors to engage with an interlocutor, to reach deep into the past, but also to share memories of life after repatriation or resettlement. They contribute to the depiction not only of a macro-historical event but also of states of mind ranging from severe to lesser forms of post-traumatic stress. It is important to understand that what is being videotaped is also the survivor’s presence—a “Here I am” greater than the sum of the words exchanged or the impromptu back-and-forth within each testimony.

At the time Yale was establishing its archive, Claude Lanzmann was close to finishing his masterful film Shoah, not released until 1985. It too depends primarily on survivor interviews. But Lanzmann is not at all concerned with offering psychological support to the survivors. His overriding aim is evidentiality. He interviews even some perpetrators to expose the machinery of the extermination, using a hidden camera as well as canny questioning. But mainly he persuades the film’s survivor-witnesses to testify on the very ground, the site where thousands of their companions were murdered—sometimes twice over, as when corpses were dug up again to be burnt in a hellish effort to cover up what was not incinerated before. This is Lanzmann’s way of making heard the victims’ blood crying from the ground (Genesis 4:10). He is putting a truth, that the Shoah existed, irrefutably on record, sometimes even forcing the survivor to reenact the traumatic scene of their own deepest anguish.

The Yale video testimonies work very differently. Not only are the interviewers trained to be the opposite of overbearing, but what is elicited by them from the survivors is, as historical, factual information, quite limited, especially when it reflects the lowly position of Jewish prisoners in the Nazi camp’s hierarchical system. By 1980, moreover, both the parent-survivors and their present family, the second generation—the latter perhaps expecting children of their own—are in search of a “legacy” that is more than a mysterious wounding that dominated the past and sealed it off.

The testimonies, then, may have the strength to convey into the future what we can bear to remember. They grip rather than freeze our emotions in that we do not have to see and try to absorb animated photos or cinematic recreations of the atrocities themselves; we see and hear those who suffered them, and who still deal with them, as memory returns. The pedagogical and humanizing value of this oral literature includes expressive moments that may not be sustained or sustainable yet often match in their intensity those from our literary and cinematic canons.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Geoffrey Hartman, Emeritus Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Yale, is Project Director of the Fortunoff Video Archive. His latest book is The Third Pillar: Essays in Judaic Studies.

Geoffrey Hartman, Emeritus Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Yale, is Project Director of the Fortunoff Video Archive. His latest book isThe Third Pillar: Essays in Judaic Studies.