Harold, the birthday boy of Mart Crowley’s 1968 play The Boys in the Band, makes no apologies when he arrives late and stoned to his own party. “What I am,” he announces moments after entering, “is a 32-year-old, ugly, pock-marked Jew fairy, and if it takes me a while to pull myself together, and if I smoke a little grass before I get up the nerve to show my face to the world, it’s nobody’s goddamned business but my own.” In one fell swish, the character of Harold brought together decades of Jewish and gay anxieties around assimilation and acceptance, adding with a grin, “And how are you this evening?”

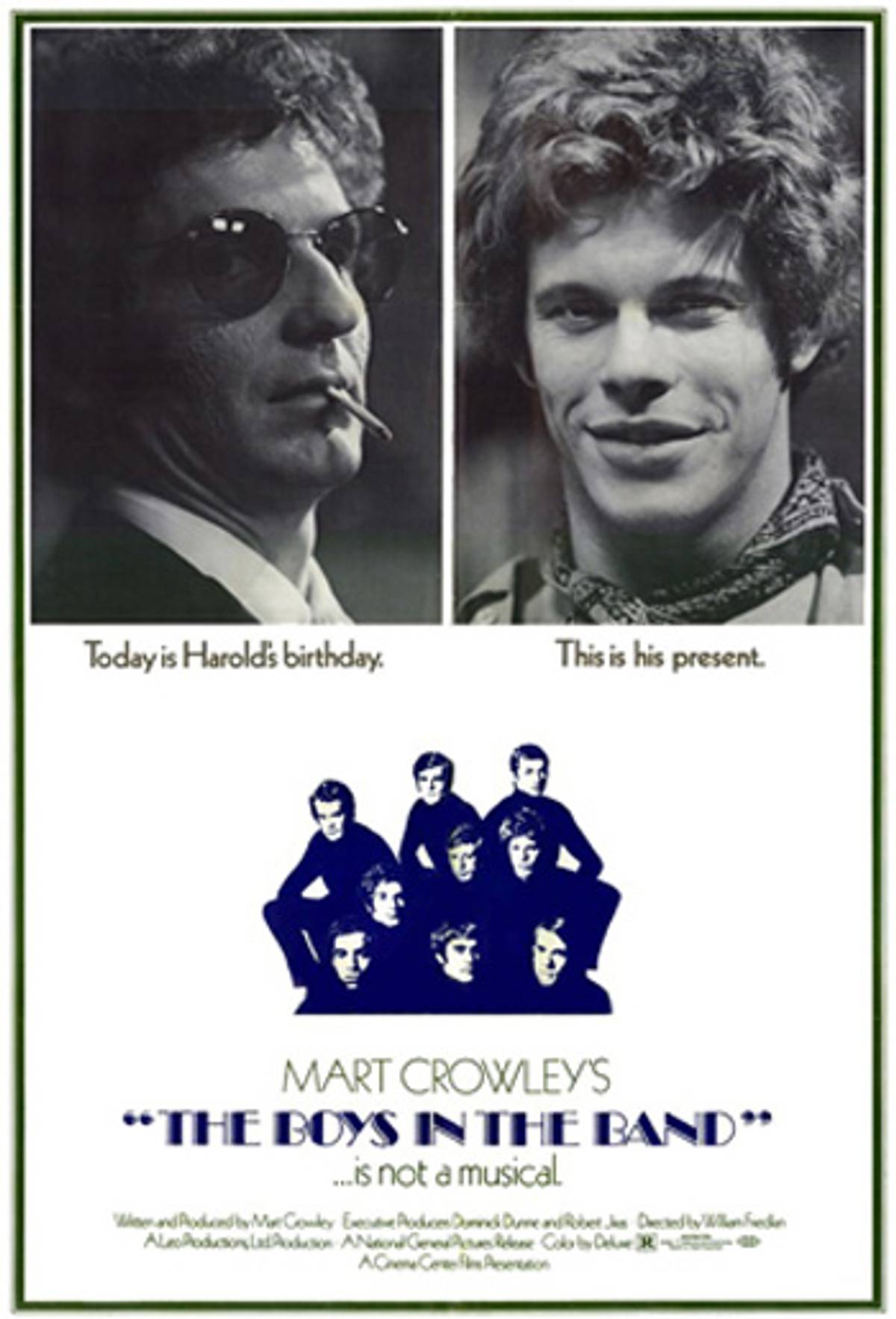

Audiences old and new can now welcome Harold, played with captivating precision and mystery by Leonard Frey, into their own living rooms, thanks to the bonus-laden DVD release of the 1970 film. The high-pitch-perfect cast remained intact from the 1968 off-Broadway production, which ran for 1,001 performances, and moved with apparent ease to the screen under the direction of a pre-French Connection William Friedkin. But the standout actor is still Frey, with a haircut to make Elliott Gould jealous and a fashion sense worthy of Oscar Wilde. He steals the scene even before he arrives: the film opens with a glimpse of Harold in his bathtub, listening to “Anything Goes,” yet the audience, like the partygoers, spends the first 45 minutes of the film anxiously awaiting his entrance.

Today the plot reads like a pitch for a Logo reality show, but in 1970 it was truly groundbreaking for a mainstream film: eight gay men gather in a New York apartment for drinking, dancing, and bitching. Together the eight men look like a cross-section of New York’s gay community, each balancing a host of identities and desires, whether Harold’s best friend Michael, a recovering alcoholic beset by Catholic guilt and credit card debt; Bernard, an African-American bookseller; Emory, an antiques dealer who ends every other sentence with “Mary”; or Hank, a beer-drinker who’s left his wife for Larry, a fashion photographer. The twist comes when Michael’s old supposedly straight college buddy Alan arrives at the party: Michael’s never come out to Alan, and begs his friends to “cool it” for a few minutes—”no camping!” he tells Emory. But while the challenge throws the other characters into crisis, Harold lights another joint, eats a slice of lasagna, and deadpans, “Although I have never seen my soul, I understand from my mother’s rabbi that it’s a knockout. I, however, cannot seem to locate it for a gander.”

Frey knew a thing or two about rabbis. He made his Broadway debut playing Mendel, the rabbi’s son, in the original 1964 stage production of Fiddler on the Roof. A year later, he took over the role of Motel the tailor, a part he’d play again in the 1971 film version, earning an Oscar nod. Yet Frey’s move from Pale of Settlement to late-20th-century Manhattan and back again may not have been all that difficult: both Fiddler and Boys in the Band grapple with the assimilation anxieties and identity politics of the 1960s, ranging from gender roles to ethnicity to sexuality.

Tevye’s trials begin when he must decide whether to break with tradition and allow his daughter Tzeitel to marry Motel, the man of her choice. Yet while Tevye’s family moves, marriage by marriage, towards assimilation, the musical itself was a proud revival of Jewish heritage, that spoke to generations of American Jews seeking new ways to identify culturally and spiritually.

In the late 1960s, the gay community, too, found itself torn between struggling to “fit in”—acting “respectable” and accepting, in Michael’s words, that “some people do have different standards”—or being themselves and risking visibility. What was, and is still, canny about Harold, both in Crowley’s writing and Frey’s performance, is how he brings together all these old and new anxieties about identity, Jewish and gay, without providing a perfect solution to any of them.

Harold may not be entirely at ease with either his sexual or religious identity, but he refuses to downplay or mask either—that phrase “Jew fairy,” barely a pause between, acknowledges bigotry and persistent self-loathing at the same time it defies both. At the party’s end, Donald, another partygoer, says he hopes to see Harold again soon. “Yes,” Harold answers, “Maybe next Shavuous?”—not Passover, or Rosh Hashanah, but a reference that hints at Harold’s religious upbringing while leaving Donald (and many audience members) outside. However Harold might actually feel about himself, his humor provides a crucial mode of resistance and resilience—a way of accepting and performing identity while still holding it at a critical distance. One can see a similar strategy on display in Portnoy’s Complaint or the stand-up of Lenny Bruce, as well as the camp humor of later gay artists such as John Waters, Charles Ludlam, and even Tony Kushner. Reviewing the play in the New York Times, Clive Barnes went as far to call the “New York wit” “little more than a mixture of Jewish humor and homosexual humor seen through the bottom of a dry martini glass,” though he never considers what Jewish and gay humor might have in common—namely, a half-mocking performance of identity that cuts to the punchline before anyone else can.

The Boys in the Band was greeted with contempt by some gay critics as early as 1968, even as gay and straight theatergoers flocked to see it off-Broadway. The Advocate accepted Crowley’s right to depict unhappy gay characters, but worried that mainstream audiences would think homosexuals were all in all a miserable, tragic bunch. By the 1970s, when the gay liberation movement got under way, the prognosis for the play and film looked even worse: its portrayals of gay men were thought to be too negative and caustic for an age in desperate need of positive imagery. The responses echo some of those Philip Roth heard a decade earlier after the publication of Goodbye, Columbus from the Anti-Defamation League as well as others—why did he insist on portraying Jews in a “negative” way? Roth replied in Commentary, “If there are Jews who have begun to find the stories the novelists tell more provocative and pertinent than the sermons of some of the rabbis, perhaps it is because there are regions of feeling and consciousness in them which cannot be reached by the oratory of self-congratulation and self-pity.”

I am too young to have seen Boys in the Band when it premiered on stage or on screen. Yet I find its portrayal of gay life more familiar than I would have expected. Some viewers then and now deny what’s fun, even redemptive, about the film, and dismiss it as mere confirmation of the depressing state of queer community before Stonewall—or, in the words of one current Advocate critic, an exhibit from “Mary’s Natural History Museum.” But while much has changed since Boys in the Band was written, it portrays anxieties about acceptance and assimilation that we all continue to grapple with. Until that changes, if it ever does (or should), I’m sticking with Harold—a queer Jew who defiantly struggles to be himself, no matter what his mother’s rabbi has to say about it.