‘Homeland’ and ‘24’ Creator Howard Gordon on Terror, Tyranny, and TV as Art

The man behind post-Sept. 11 TV opens up about his background, what goes on in writers rooms, and what he’s working on now

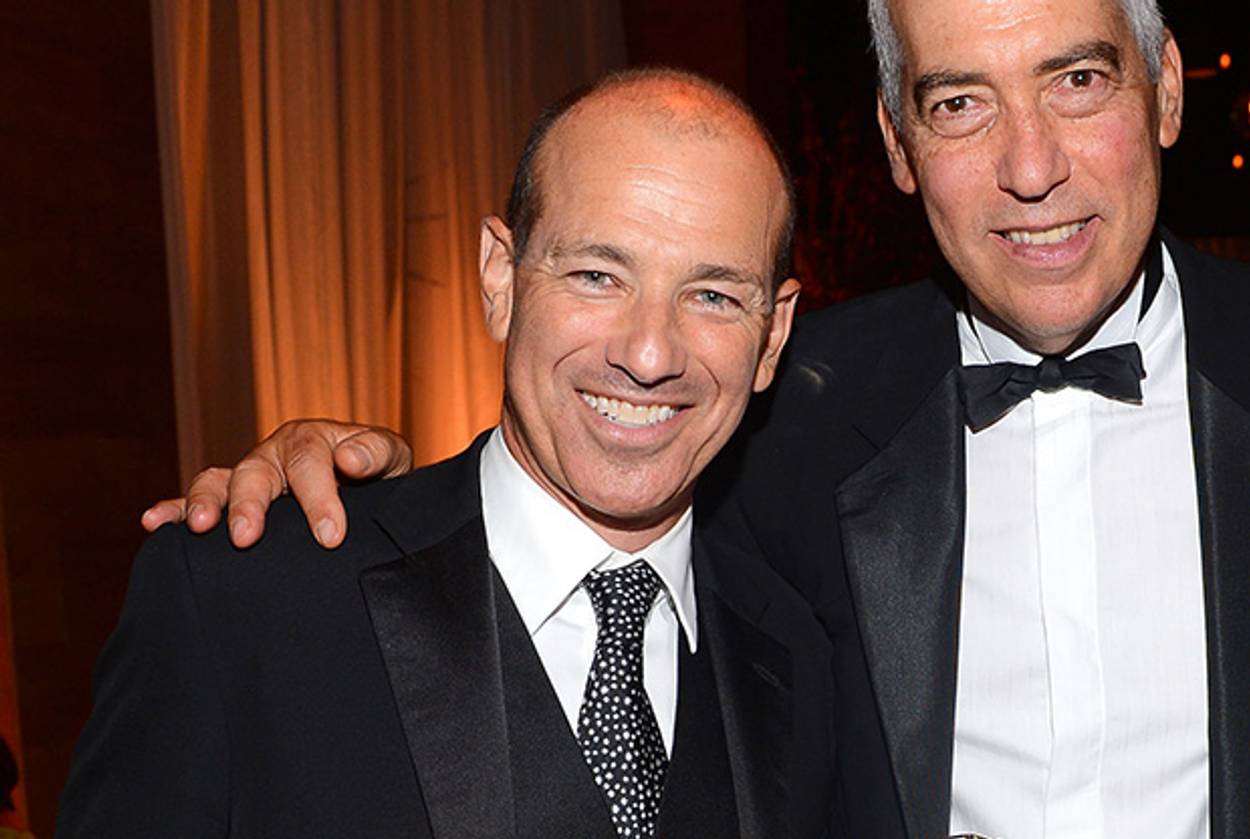

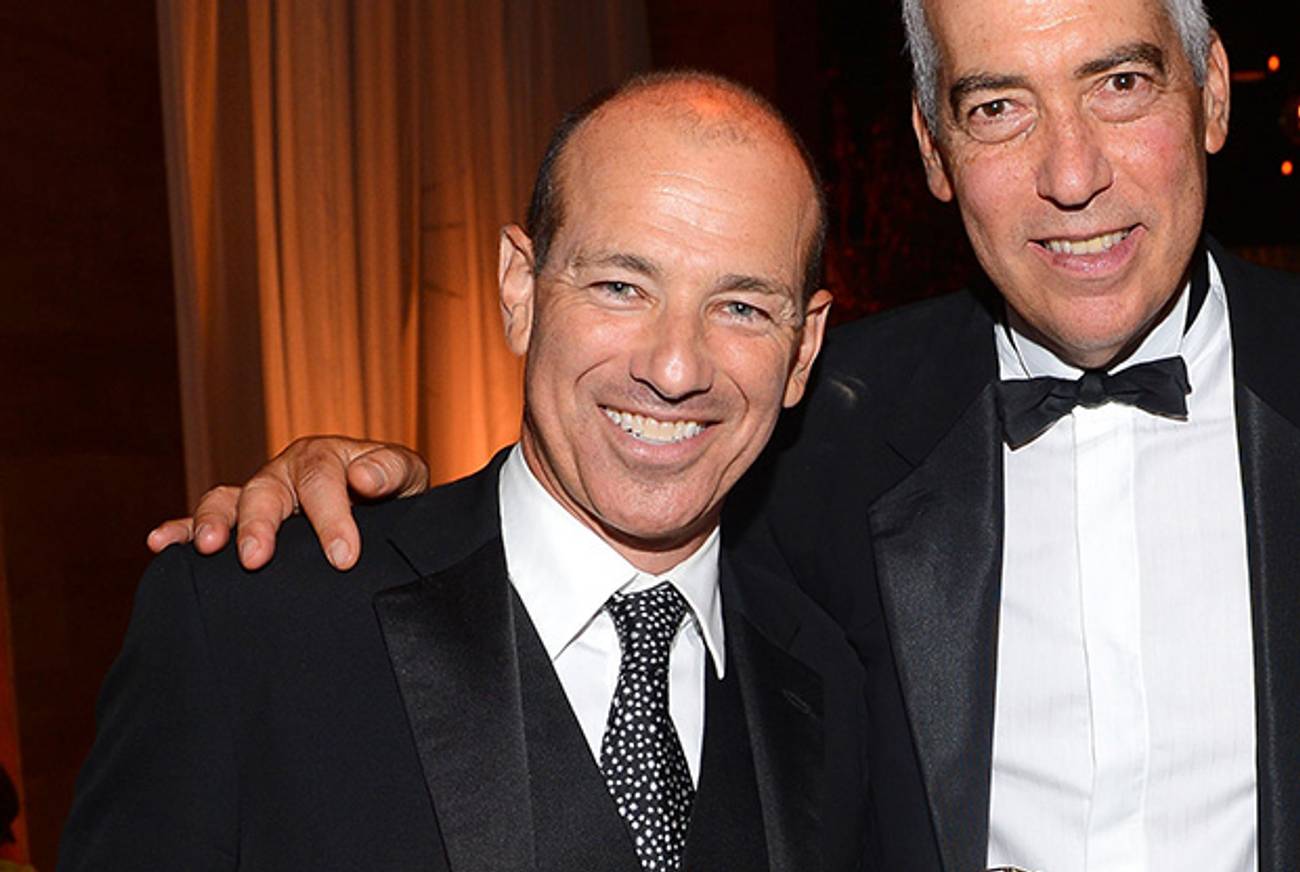

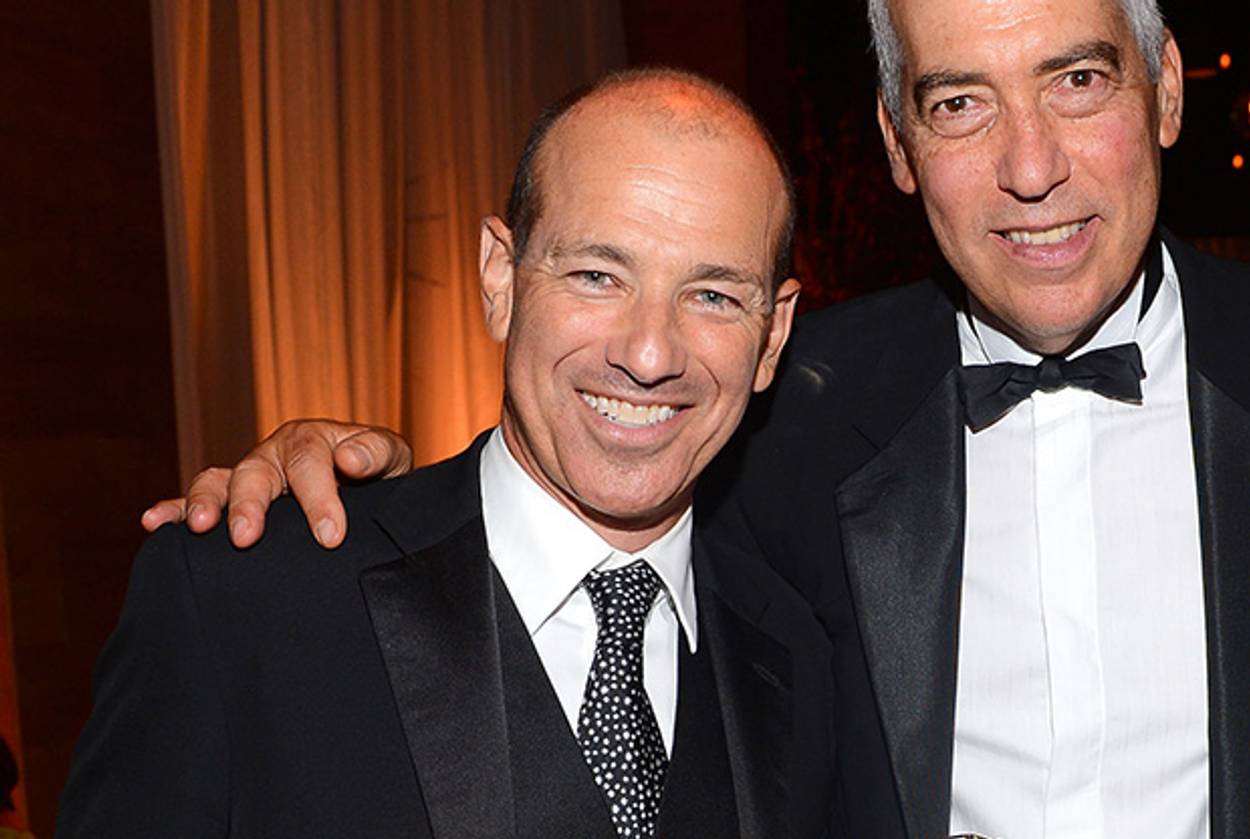

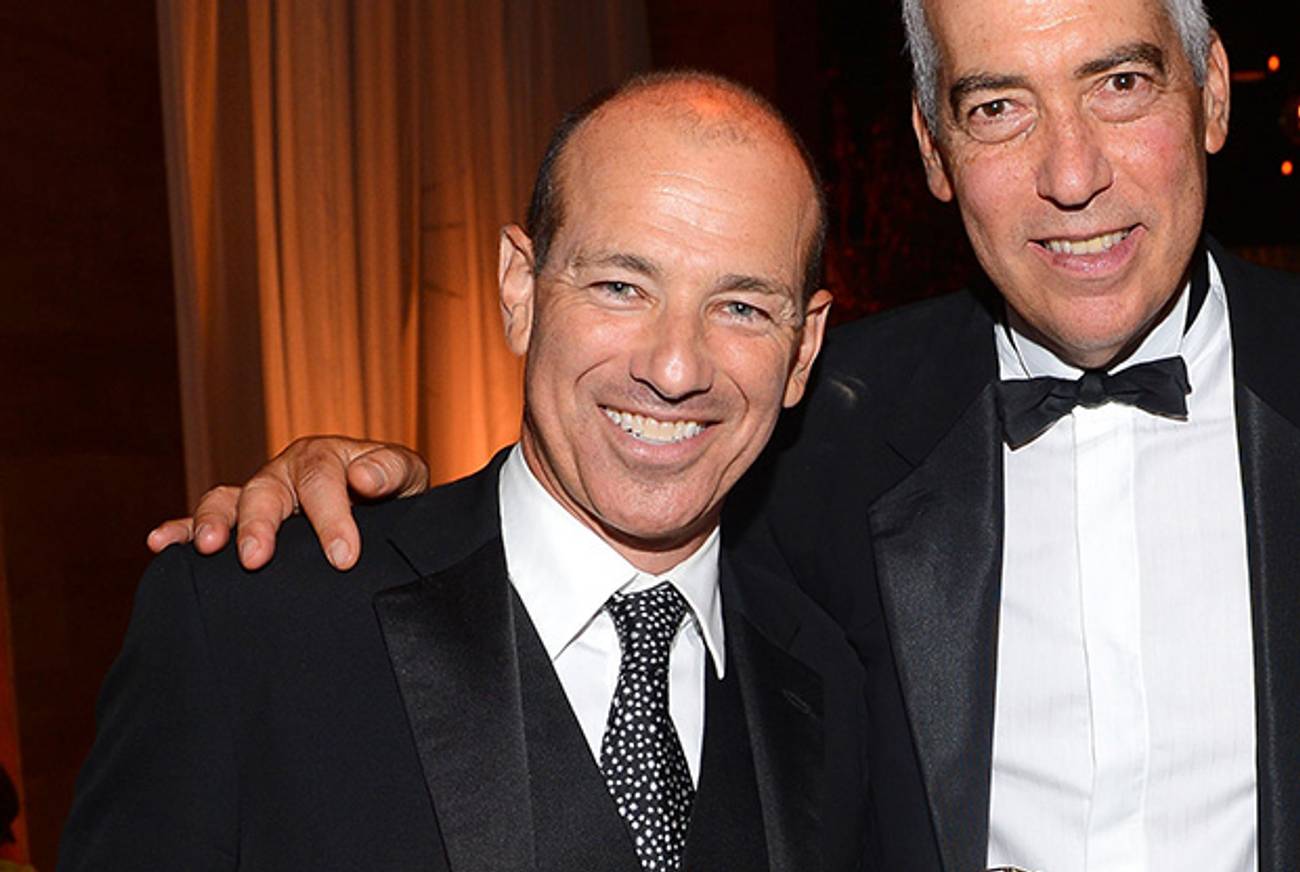

The most surprising thing about meeting Howard Gordon in person is how calm he is—you would expect the writer and producer behind such shows as 24 and Homeland to radiate just a touch of the existential anxiety his work so potently explores. But on a recent afternoon in TriBeCa, New York, the poet of ticking time bombs and countdown clocks—who had just come from having pizza and a CitiBike ride with his wife, Cami—was thoughtful and laid back as he discussed his path from Long Island to Hollywood fame.

Which, on second thought, isn’t surprising at all: For all of their quivering, mad energy, Gordon’s shows are always much deeper than their surface suggests, concealing profound philosophical and moral questions beneath their suspenseful and fast-paced veneer. In 24, he explored the ever-shifting position of America in a post-Sept. 11 world, which meant looking at everything from torture to political corruption. Homeland went even further, with greater psychological nuance and with America’s foreign policy in the Middle East constantly serving as a bold, dramatic backdrop. And so, when Gordon talked to us about his love for Saul Bellow—that other great American chronicler of power and its limitations, mortality, lust, community, and redemption—it seemed only natural.

As Homeland returns for its third season, we talked to Gordon about mastering the structure of TV storytelling, taking and ignoring criticism, and what it means to be an American. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

***

Alana Newhouse: What is it you’re doing in New York tonight? Giving out some award?

Howard Gordon: I’m being honored by the Auschwitz Jewish Center Foundation, at the Museum of Jewish Heritage. My mother is a docent there.

AN: I didn’t know you were actively involved in Jewish causes. What’s your connection?

HG: I had a pretty standard Long Island Reform Jewish education, went through bar mitzvah and confirmation, and went to Israel a few times. I went on a teen tour as a kid, and I went again with my family for my brother’s bar mitzvah. I was sort of raised on the narrative of the land of milk and honey and found myself growing up very, very acutely aware of the Holocaust.

AN: Did you have Holocaust survivors in your family?

HG: I did. My mother’s side of the family has a number of people who perished in Auschwitz—first cousins and aunts and uncles. The survivors actually wound up resettling in Los Angeles, so as a kid I had this strange relationship with L.A. where I would go out there and see all these old people playing pinochle with tattoos. And I’ve always identified as part of this tribe, which I always wrestled with. I’m not terribly religious, but I do find comfort in the traditions. We don’t strictly observe Shabbat, but we certainly light the candles—and we appreciate the idea of it. As you get older, you appreciate the wisdom of those things. When my kids didn’t want to go to Hebrew school, I always likened it to a garden, a very thick old garden that has been around for 4,000 years. You can’t always see your way through it, you don’t always know which way is out, but you do not want that garden to die while you are in it. I like being in the garden. I like being a part of it. And it’s something I want them to wrestle their way through.

AN: How many kids do you have?

HG: Three: 20-year-old boy, 17-year-old girl, 8-year-old boy. Same wife.

Liel Leibovitz: The Hollywood disclaimer.

HG: Believe me—because everyone assumes not.

AN: Let me start with an easy question. If somebody were to do a profile of you that was actually accurate and it contained that one great New Yorker-esque line that summed up the big theme that runs through all of the stories that move you, what would it be?

HG: That’s interesting. I’m going to answer with a negative answer. I’ve often said my biggest fear was that my epitaph would say ‘he had a way with words and no point of view,’ but I think I’ve come to embrace that I’m kind of a journalist, a fly on the wall. I feel like a medium or passage of stories, a broker of stories, not necessarily as someone with such a strong voice but a channeler of other people’s voices and other stories. I’ve had a nose for stories. I would say that my reputation has been built in 24 and Homeland and hopefully now with Tyrant, so I think I have this obvious attraction to the center of gravity about them. In some ways, terrorism is just the tip of the iceberg of what I am interested in: It’s about power, it’s about politics, and it’s about people, and it’s about our world and how our world has changed since 9/11, which was a huge moment for me.

AN: Where were you?

HG: I was in L.A..

AN: Why was it a huge moment for you?

HG: Because it felt as though this thing that I had been dimly aware of had cracked open, and I felt like the world had tilted on its axis and wouldn’t right itself again. It was an earthquake of a kind. It was actually an aftershock: You realize that that story didn’t start on 9/11, it’s an old story, it moved forward in time and backward in time, and it opened up a whole thing that has been very interesting for me.

LL: When 9/11 happens, the very first moments, before we know anything and we are all scrambling to tell ourselves a story, to explain what had happened, to go back, what’s yours? What do you tell yourself? What just happened here? Emotionally, immediately …

HG: It’s a great question. It sounds like ‘how can this have happened? How could this be?’ Because it didn’t make any sense. It challenged all the parochial views that I had and my understanding of the world, which was admittedly a Pollyanna-ish, glossed over, pasteurized version of history and of our place in it, meaning our place as Americans and what’s our part in the world. So, it really made me ask what it is to be American. It made me wonder, it made me own being an American, in all its sort of American exceptionalism. I actually happen to be a big believer in this place and in its values, that America is this idea, that we are this country that still navigates multiple ethnic and tribal religious populations and makes it work somehow. The fact is that we negotiate our way and mediate against these very strong tribal impulses that people seem to have everywhere else but here. We have them here, but we seem to moderate them and sublimate them. That, to me, represented something worth getting in touch with and understanding more deeply. Including all the problems, all the bad things America has done and is capable of doing. I became very interested in what it means to be American.

LL: How do you get from that moment, from these tremors, to Jack Bauer?

HG: We were actually shooting the fifth or sixth episode [of 24] when 9/11 happened. Suddenly we had this show, one that hadn’t even aired yet, and it was the zeitgeist. That suddenly became the prism through which so many people viewed the world, and I joined on the bandwagon. Jack Bauer became this guy that who was adept at navigating the failure of bureaucracy that we had suffered, that we couldn’t be protected by our intelligence agencies, that they didn’t see this coming, this massively plotted attack. Jack became the guy who cut through the bureaucracy and went after the bad guy in a very American way. And he did it in a day! I mean, talk about fast service. That was in some ways the most binary narrative.

The other side of it was that I was accused of promoting Islamophobia, promoting torture. Jack did nothing that Arnold Schwarzenegger or Bruce Willis or Clint Eastwood in Dirty Harry didn’t do. And by the way, no one mentioned a thing until Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo, which shows you the dance between television and current events. Jack Bauer in the first few years after 9/11 was a total hero. Suddenly, after Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo, Jack Bauer is a little darker. Suddenly, what Jack does isn’t so kosher anymore. So, a character now has to account for his own existence in the real world.

AN: You can’t control current events.

HG: Jack became a dark, conflicted character, and he even had to confront a new reality. How do you do that without denouncing the essence of the series itself? And saying that Jack is a torture-mongering Islamophobe?

LL: So, here you are finding yourself accused of all sorts of things that I imagine were very new and jarring for you to hear, to learn that you’re that guy. So, do you … What does one do?

HG: You have to listen. You have to ask questions and not have the answers. You really have to stay fluid enough to say, “I may not believe Jane Mayer’s article in The New Yorker entirely, but there’s something here I can’t ignore.” Jack has to account, as a character in the fictional world of 24, for the way that our country had to answer for Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib. He had to acknowledge that it’s not that easy. That if he’s going to do this, if he’s going to be a tough guy, and he’s going to shoot first and ask questions later, that there’s a price to be paid and he’s going to have to pay for it, he’s going to have to feel guilty at the very least, he’s going to have to at least understand that it’s not that simple. That he’s made mistakes.

LL: Is this the post-Sept. 11 theory of television? That we should all be less interested in answers and more interested in questions?

HG: Yep. And I think that it’s a good philosophy in life, too: People with too many answers are people to be worried about.

LL: We’ve seen ironically little of that before.

HG: When I grew up, my early television mentors told me something very didactic: Your heroes can’t make mistakes. I’m amazed that was even ever true.

LL: Speaking of early mentors, let’s pull back for a minute. How did you get into television?

HG: I assumed I would be a doctor or a lawyer. There was no other path for people in my world. My father was a dentist, my mother was a school teacher and a guidance counselor, and there weren’t that many paths for someone who wanted to make his living making things up. But I had a really acute failure of imagination—I realized after I graduated that I hadn’t taken any science classes, so I wasn’t going to be a doctor, and then I overslept for the LSATs. But I’d always loved television. I was a poet, actually. I wrote poetry and I wrote short stories, but I loved television. It wasn’t ever movies—I never aspired to write movies. I just grew up on television in my house, but I knew no one and had no connections and didn’t even know what a script looked like.

LL: Wait, so you’re 8, 9. What are you watching?

HG: Star Trek, That Girl, Room 222, Brady Bunch, I Love Lucy, Batman.

AN: When you say you loved television …

HG: Roots! It made me think about my life, what it was to be alive. Roots was seminal. TV movies like That Certain Summer or Brian’s Song, this was a golden age of television back then that was so immersive.

AN: Did you see TV as an art?

HG: I did. I had none of the sort of parochial view of television, that it was an idiot box. I took it very seriously. I was aware of the level of wit and cleverness and also immersiveness. A movie is a two-hour event. Somebody can work on a movie for years and years, the lights go down and they go up and you go home. But these TV characters that you live with from week to week and year to year was something that was very powerful.

LL: Having kind of been in this position myself as a kid, and having a lot of friends who did this, when you start understanding that you’re very serious about TV, you start to think about it a lot. You analyze. What were you noticing that you liked about particular shows you followed?

HG: I don’t think I grew up articulating this or being conscious of it, actually. I just really did not know what else to do. I had nothing else to do. I actually had applied to graduate school in creative writing and found myself more interested in trying at a television career. Again, I didn’t know how one even went about it. I didn’t know anybody who did it. But I was young enough to go out to L.A. with my partner Alex Gansa—who, like me, was an English major who also had no plans—and so I convinced him that I had this great idea for a miniseries on the life of Lord Byron. We got out there, and as it turned out no one was interested in Lord Byron. And I couldn’t even get my hands on a script, to learn what it looked like. So, we literally transcribed scripts of television shows we had taped by hand and broke them down on index cards. That was our crash course the summer after graduating.

AN: You autopsied them.

HG: Pretty much. We deconstructed television episodes of shows we liked—St. Elsewhere, Hill Street Blues. I was more of the TV fan, Alex was not. He and I had forged a love of Saul Bellow. We were both huge Saul Bellow fans.

AN: Favorite Bellow story?

HG: Humboldt’s Gift. Herzog is great, but Humboldt’s Gift. I was fascinated with Delmore Schwartz. Anyway, we went out there and we became SAT tutors. I started an SAT preparation company, and we were very successful. Had I stayed doing it, I might be publicly traded now. … Instead, one of my students was the daughter of a producer who offered to read our St. Elsewhere spec script. He read it and invited us to pitch stories. In those days you could be a freelance writer. That doesn’t exist so much anymore. There was actually a time when there was an executive producer and one or two story editors, and the rest were freelanced out. Those were the days you could actually schlep your story ideas and pitch them, sell it like Willy Loman and then go to the next show. That’s what we did. Within a year, by 1984, six months after getting out there, we landed our first script. I have not stopped working since. If you graphed my career it has almost been at 45 degrees. It’s had some zigzags but I’ve been mostly employed since 1985.

LL: What do you learn when you make the transition from a kid who’s sitting and listening and transcribing to, say, your third gig in?

HG: Here’s the amazing thing about writing: I am humbled by it every single time. You’d think at this point you could reverse-engineer a hit, but you really can’t. It’s not like building a box or a house. It’s just not schematic. It’s new every single time. When you face a page you don’t know what the tone is, you don’t know who the characters are, and it beats the hell out of you. I fail a lot. There are many scripts and many ideas that fall apart because the DNA is messed up. There’s no falsehood or modesty to this; it’s a punishing process and you need to maintain that humility and that openness to the realization that it is really hard and that you need to get lucky at every step along the way because so many things can go wrong—you write a bad script; it’s good but you cast it wrong; you give it to the wrong director. It only takes one thing to go wrong to mess up the whole enterprise. It’s humbling. And horrifying.

AN: One of the things that interests me is that TV—and a specific kind of TV—has become clearly more sophisticated as Freudian psychoanalysis has gone out of favor. But you are obviously driven by the idea that characters are motivated by certain drives and impulses. And yet it’s almost as if people still can’t handle that idea …

HG: They outsourced it.

AN: Yes. There’s a lot more of this thinking—about who those characters are, what their backgrounds are, and so forth that goes on but that we never see. How much filigreeing do you guys do?

HG: More than you think. I was actually one of the last analysands in Beverly Hills. I was on the couch for many years. The analytic process is one that’s very personal to me. I think you’re exactly right; every character is deeply imagined and deeply considered and the history so much more known than what’s shown. And what’s really fascinating about it is that unlike a novel, the writers room is filled with people imagining this character together. These characters live in the ether in the writer’s room, in our collective psyches.

AN: Which means those characters are inevitably reflections of all of you.

HG: Very much so.

AN: Let me ask you about another show: Homeland. My feeling about it is weirdly related to my feeling about Rescue Me, which felt to me almost like Shiva for New Yorkers. I think for some viewers—myself included—it was very hard for it to end because it was like “And now we’re not going to mourn anymore. Get back to your life.” In a funny way I feel that about Homeland, too. How do you end a show when the circumstances around it haven’t ended?

HG: Did it pick up the torch where Rescue Me left off in your mind?

AN: In a way I think it did, though they’re obviously such different shows. But my question is: Do you get anxious about what a show is doing to viewers not just as entertainment or as art but what it’s actually doing emotionally for people?

HG: I’m stepping back from the show a lot this year. The emotional responsibility it has now rests far more squarely on Alex’s shoulders than on mine. But I know that feeling, and I know the crushing, punishing, debilitating effect that it has. You do feel a tremendous responsibility to the audience and to your actors and to yourself and to the story as some sort of entity that’s out there and needs to be told right and you need to honor that. And part of it is stubbornness and part of it is pride but part of it is just honoring something that you take very seriously. We didn’t set out to create a national anthem or to create an allegiance of addicted fans, but the more people like it, the more worried we get that we are going to let them down.

LL: Do you ever get enraged by the reactions? Do you ever see certain elements that viewers take and think, “This is what you’re focusing on?!”?

HG: I’m self-loathing enough and self-doubting enough that it just tends to corroborate some deep doubt that I have. And a lot of these people take pot shots at what’s clearly the Achilles heel of an episode. I always want to reach into the computer and say the opposite of the Nike thing: YOU just do it! So, yes it is enraging occasionally. But that’s why I don’t look at it anymore. Critics included.

AN: You don’t read anything?

HG. Alex really reads these things carefully, and there really is some astounding criticism. The level of criticism has risen with the level of television. It is positively Talmudic. And it’s also become a legitimate area of study in academia. My son is writing papers on Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Larry David. These are my friends! I say “I’ll call Joss, I’ll call Larry.” It’s very funny that this stuff is being taken so seriously.

AN: There’s a Talmudic story in which two rabbis are fighting about the meaning of a particular law—what God intended it to be. Rabbi A finally says, “You know what? Let’s just ask God.” And God says “It’s what Rabbi A says.” But then Rabbi B is says “Well, too bad. You gave it to us and now it’s for us to figure out.” Larry David’s opinion about what he’s trying to do doesn’t matter.

HG: Wouldn’t it be funny if Larry David wrote like a paper on his own stuff and got, like, a B?

AN: Exactly. So, what are you focusing on now? Are you actively seeking other projects, and if so, how do you find them?

HG: It’s simple. If I feel excited by an idea, if I feel that stirring excitement, if I want to see it, then I assume someone else will want to see it as well. I’m working now on a show called Tyrant, which is about an ophthalmologist living in Orlando, he’s the son of an Arab dictator who turned his back on his family his autocratic father and his crazy Uday Hussein-like brother and moved to Florida and married a woman, an all-American woman, and has two kids. He goes back for a wedding to this unnamed country and his father dies of a stroke in the middle of this wedding, and so he winds up staying with his family in the midst of this Arab Spring-like-affected country. The country is somewhere between Syria a year and a half ago and Jordan today—and kind of every other country. I felt like this was a family drama that was really able to tell what I think is the story of our time. I think what’s happening in the Middle East and the reshaping of the Middle East is one of the most scary, exciting, dynamic stories, and being able to tell that story from the point of view of an American family was exciting to me.

AN: Do you know about Waller Newell? He’s a political scientist who studies tyrants. He’s argued, to put it roughly, that before the enlightenment tyranny was actually the norm—it was just a form of government—and that Assad, for example, would be perfectly recognizable to Plato because he is a form of tyrant that has always existed.

HG: And it’s not just tyranny of a country—it’s tyranny over your family, tyranny over yourself. And there’s a deep psychoanalysis of all our characters in this particular story.

AN: So, when do you go back to L.A.?

HG: Tomorrow morning.

AN: Well, at least you got your pizza and your CitiBike ride.

HG: It’s a great New York day. I’m so excited to be here. I miss it here.

AN: You should move back.

LL: Yeah, you can make TV from here.

HG: I plan to. I think I am going to take a sabbatical in two years.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Alana Newhouse is the editor-in-chief of Tablet Magazine. Liel Leibovitz is a senior writer for Tablet Magazine.

Alana Newhouse is the editor-in-chief of Tablet Magazine. Liel Leibovitz is a senior writer for Tablet Magazine.