In the Long History of Picture Postcards, a Long History of Anti-Semitic Hate

A newly published collection reminds that grotesque images of Jews were routinely mailed by ordinary people around the world

Click on the link to the left to see a slideshow from Hatemail.

The first anti-Semitic postcards were issued in the 1890s at the same time that postcards in general were becoming popular. In fact, there was a convergence between the start of the Golden Era and the Dreyfus Affair. In this famous incident that began in 1894, Alfred Dreyfus, a patriotic French army captain, was falsely accused of passing military secrets to the German military attaché in Paris. Even though there was no visible motive and all the evidence was circumstantial, the blame was laid on Dreyfus for one reason: his Jewish heritage. Dreyfus was convicted in 1895 in a sham trial that featured “secret” evidence that Dreyfus’ lawyer was not allowed to examine; the army invoked national security as a reason to keep the documents hidden. Even after the army became aware of the real spy and of the fact that some of the evidence against Dreyfus had been forged, Dreyfus was reconvicted in a second trial held in 1899 (after he had spent four years in harsh prison conditions on Devil’s Island). Fortunately, Dreyfus was pardoned by the French president 10 days after his second conviction, but he was still not exonerated. Only in 1906 did the court declare him completely innocent.

The Dreyfus Affair reached deep into French politics and society, splitting the nation between those who supported nationalism, the church, and a military that spared no effort to continue the cover-up; and intellectuals, progressives, and a small handful of brave politicians and army officials who wanted to learn the truth and promote an equal society. Underneath the drama was the unmistakable anti-Semitic nature of the affair and its influence on the fate of the entire nation. The Dreyfus Affair was also important as one of the factors that influenced Theodor Herzl, the founder of the Zionist movement, to determine that anti-Semitism could not be eliminated and that the Jews needed their own homeland. The affair still resonates, with new books written each year about the incident and its relevance to current events. The Dreyfus Affair was the perfect subject for postcards at the time, since it included all types of sensational events, such as political scandals, forgeries, a suicide, arrests, and, of course, anti-Semitism.

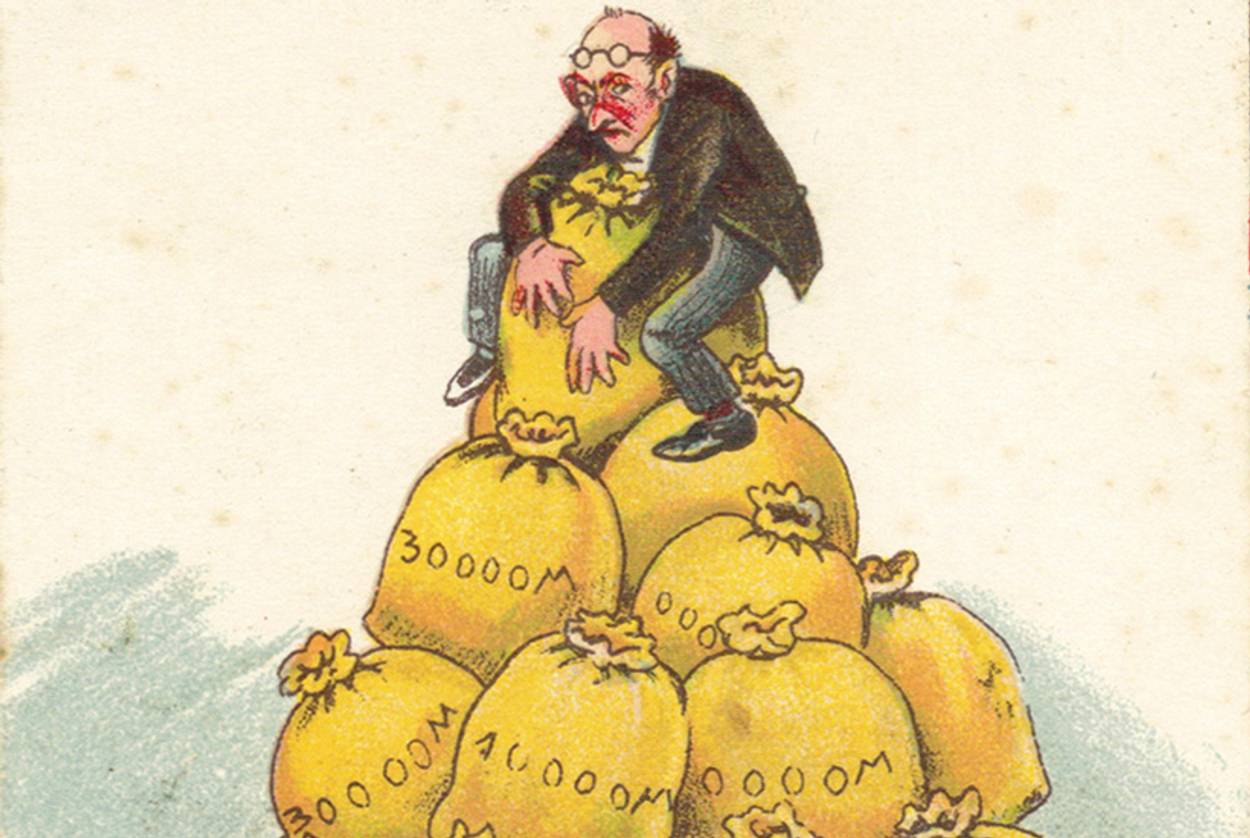

The postcards shown in Hatemail cover multiple nations, every stereotype, and every form of hatred. They depict Jewish men, women, and children with large noses, grotesque feet, deformed bodies, ugly faces, and poor hygiene; money-hungry Jews; rich, crafty, cheap, and cunning Jews; Jews in control of the world; Jews as animals and demons; and Jews as cheaters. They show Jews being ridiculed, mocked, attacked, excluded, and expelled. The reader will not be spared the full extent of the hatred; I believe many will be shocked at what is shown in this book. Even readers who have previously studied anti-Semitism and its messages might be surprised to realize the evil that could be placed on a simple postcard and widely used around the world by “regular” people living in what were considered to be enlightened democracies. Germany, France (including its North African territories that had significant Jewish populations), Great Britain, and the United States were the leaders. Austria, Hungary, and Poland were also key participants. Fewer examples are found in other nations, not necessarily because anti-Semitism was weaker, but because postcards were published in much fewer numbers in these locations. Each country’s postcards had a distinct style of anti-Semitism.

As mentioned, Germany ranked first in anti-Semitic postcards, producing images that immediately cut to the heart of the matter: Jews are filthy animals that deserve to be persecuted, expelled, and excluded from society. French postcards were a close second in their vileness. Images of Jews in control of the world or as evil or ugly money grabbers are the main motifs in French anti-Semitic postcards. Those from other nations, especially Great Britain and the United States, were sold almost exclusively as “humorous” souvenirs—but the anti-Semitism was still palpable. British anti-Semitic postcards generally avoided the worst forms of imagery, instead focusing on large nosed Jews as conniving and money-hungry. American anti-Semitic postcards are the least virulent, focusing almost entirely on images of Jews being greedy. American postcards also ridiculed the physical features of Jews, drawing not only large noses, but also large hands and awkward mannerisms. The postcards in this book all come from my personal collection, which I have been amassing for the last 10 years. The more than 250 examples depicted here are only a small sample of the many thousands of different types that were printed, but they will take the reader through the many permutations of hatred for Jews and help us to better understand a phenomenon that still exists throughout the world today.

Excerpted from Hatemail: Anti-Semitism on Picture Postcards by Salo Aizenberg and Michael Berenbaum. Copyright © 2013 by The Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska. Published by University of Nebraska Press as a Jewish Publication Society book. All rights reserved.

Salo Aizenberg is the author of Postcards from the Holy Land: A Pictorial History of the Ottoman Era, 1880–1918.

Salo Aizenberg is the author of Postcards from the Holy Land: A Pictorial History of the Ottoman Era, 1880–1918.