Bassler’s Letter: How Hollywood’s Man in Vienna Escaped the Nazis

A fascinating letter tells the gripping story of the fateful extraction of the influential film industry lawyer Paul Koretz

On the morning of March 12, 1938, Nazi troops barreled across the Austrian border, swallowing up their German-speaking neighbor in a territorial grab known as the Anschluss. Two days later the victorious forces marched through the streets of Vienna. From the balcony of the Hotel Imperial, Adolf Hitler addressed the delirious throngs who made up the fifth column that had helped doom the Austrian state. “German compatriots!” he shouted. “You all have a share in this vow, that whatever happens, the German Reich as it stands today shall never be broken by anyone again and shall never be torn apart.” Nazi-approved newsreels showed rapturous crowds waving swastikas and cheering on the goose-stepping invaders. In America, however, skeptical newsreel commentators cautioned moviegoers to remember that the pictures were taken by Nazi cameramen.

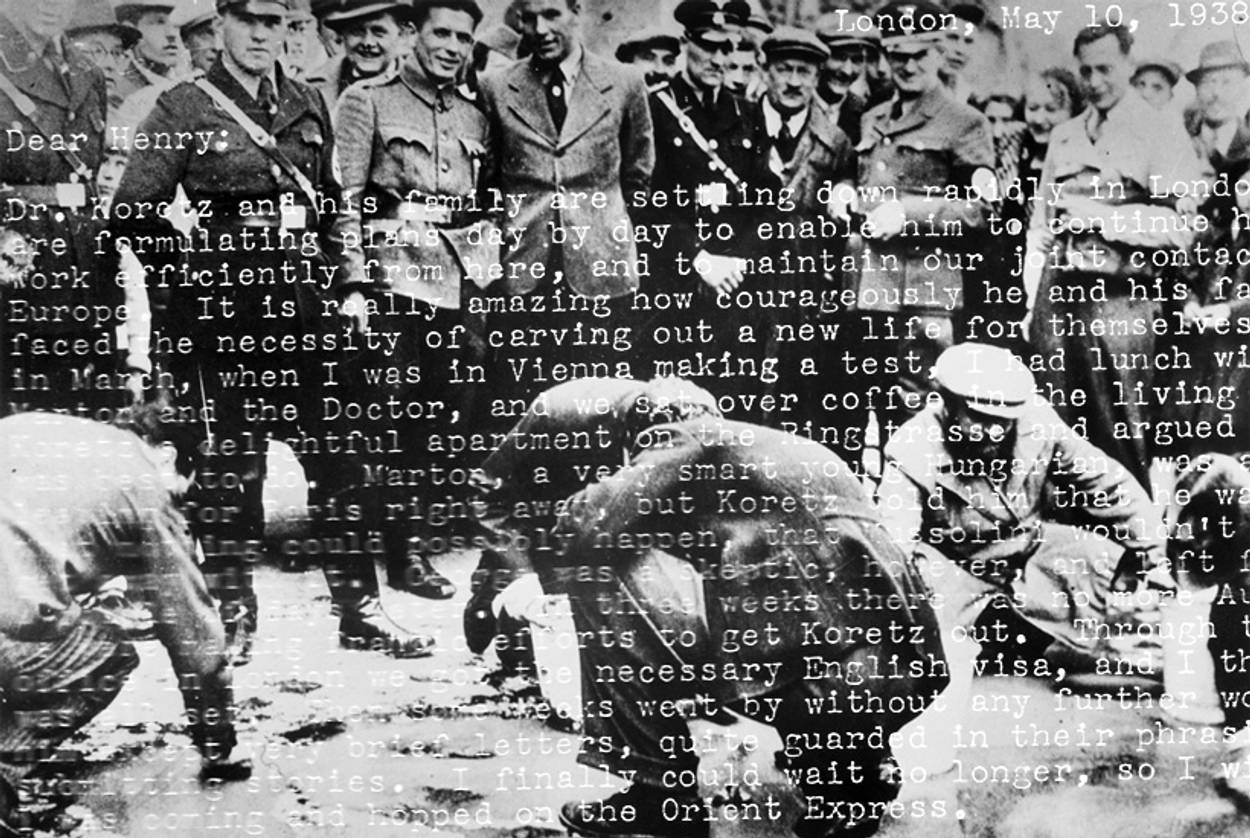

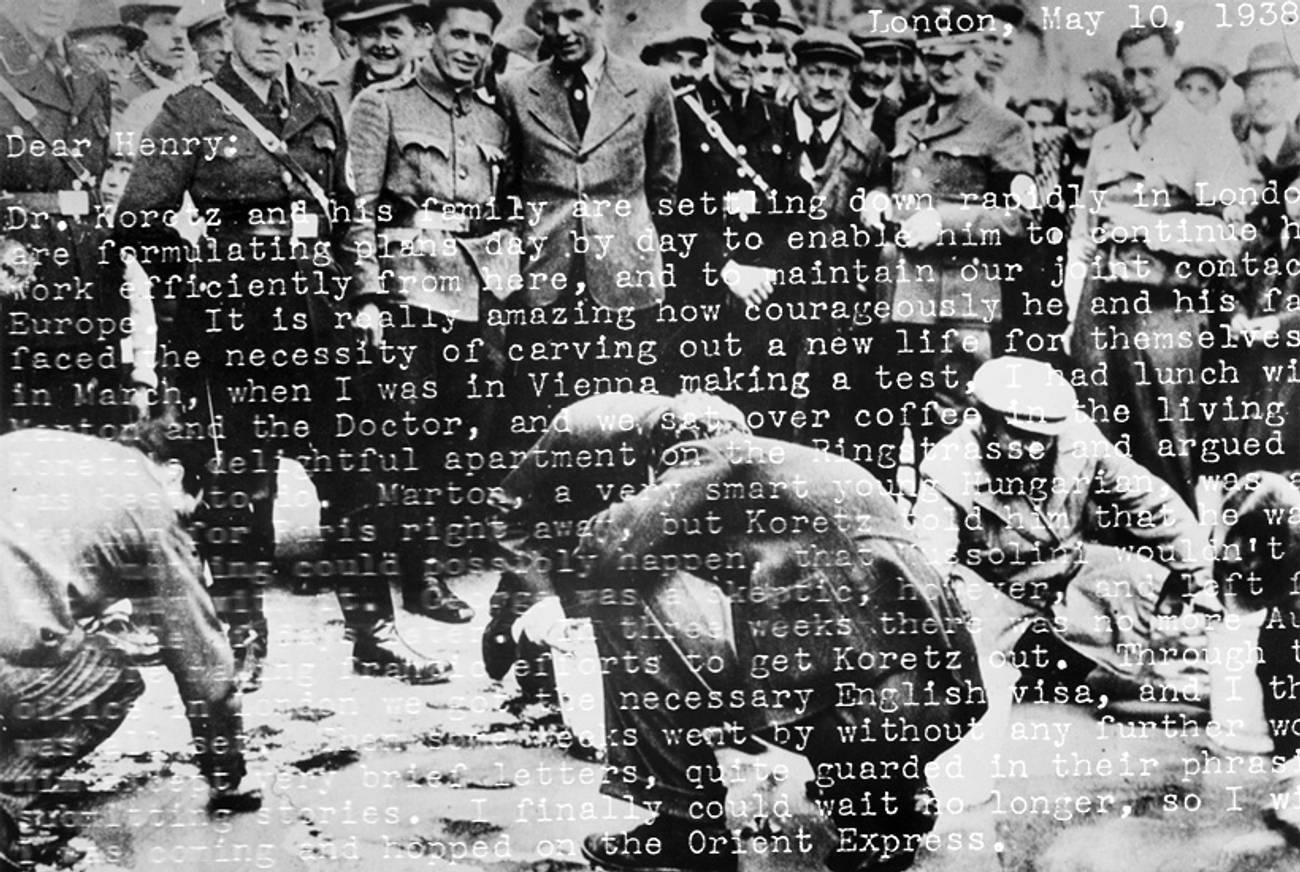

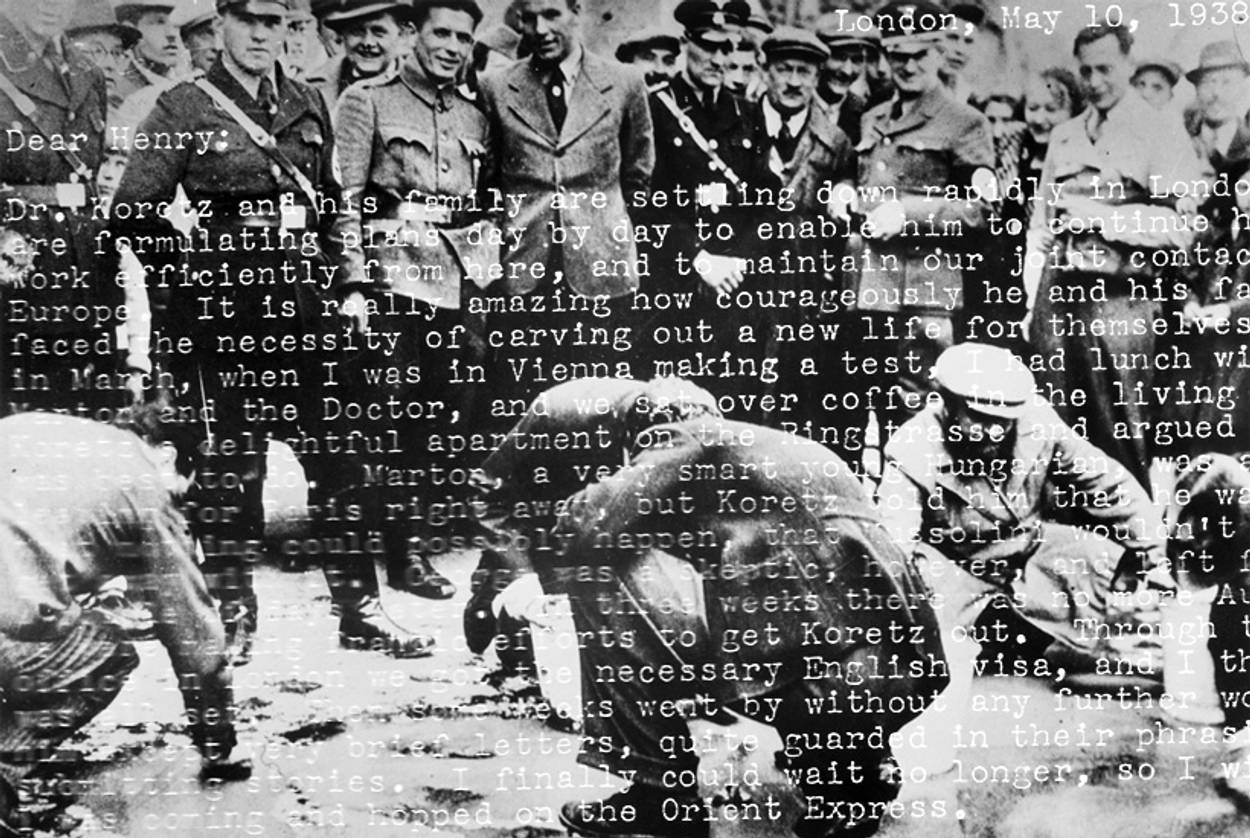

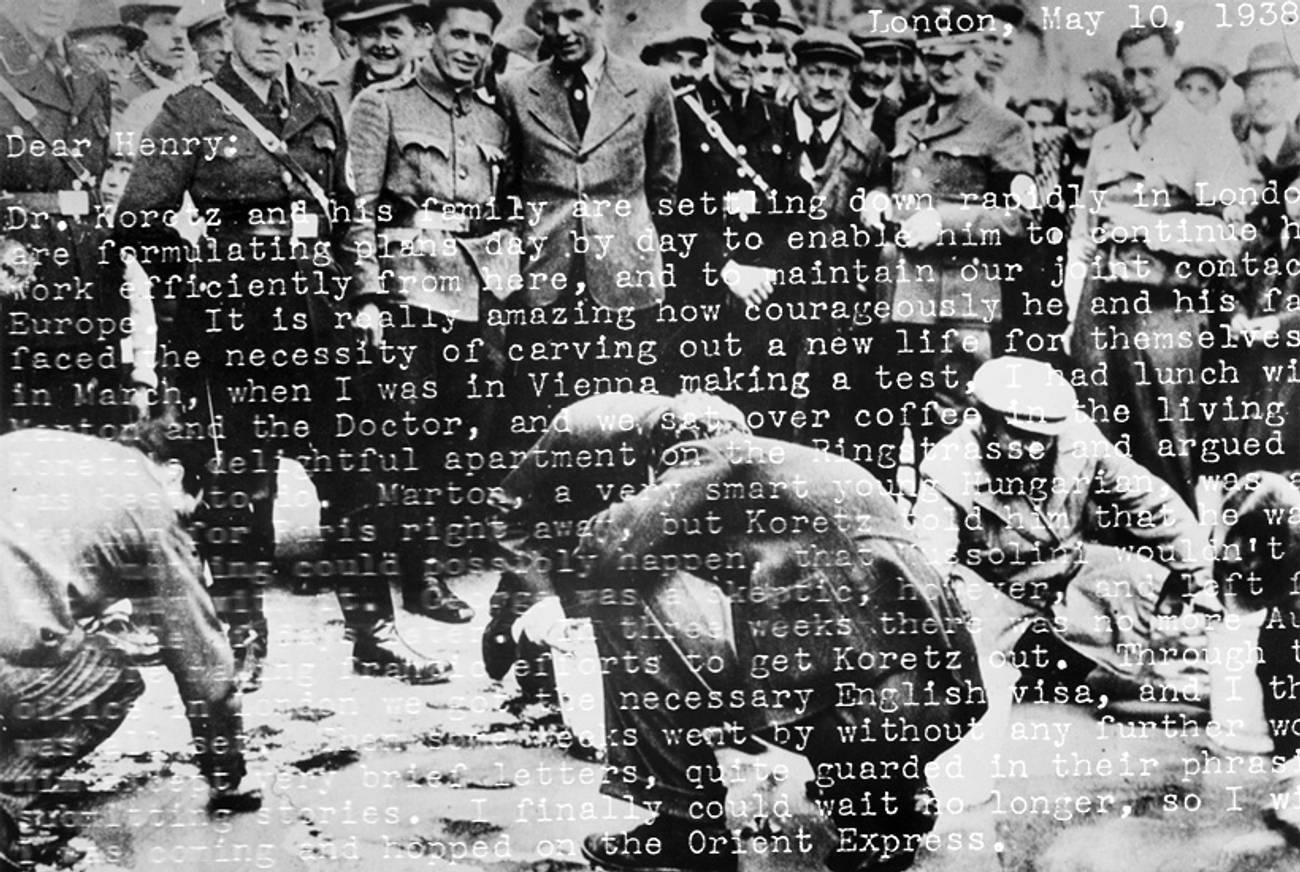

One segment of the Austrian population certainly had no reason to cheer: Jews were rounded up, beaten, humiliated. In the days to come, newspaper wire photos showed Viennese Jews on their hands and knees, forced to clean the streets under the eyes of gleeful brownshirts. “The Jewish district looked as though it had just been through a locust plague,” wrote correspondent Max Jordan, an eyewitness on the scene for NBC radio.

In Hollywood, the major studios knew what to expect—a ruthless purging of all Jews working in their branch offices and managing affiliated theaters throughout Austria. It had happened before, in Germany in 1933, soon after the Nazis assumed power. Spearheading the campaign to ensure that the art and culture of the Third Reich would henceforth be Judenfrei—free of Jews—was Joseph Goebbels, minister for Propaganda and Popular Enlightenment. Besides purging Jews from the Ufa, the motion picture production center that was the jewel of German cinema, the Reichsfilmkammer, the motion-picture arm of Goebbels’ ministry, ordered the immediate termination (at the time the word still meant only firing) of all Jews from the staffs of Hollywood’s offices in Germany, whether American citizens or German nationals. Of course, the regime was prepared to back up the ultimatum with acts of violence, official and ad hoc. Max Friedland, the nephew of Universal Pictures founder Carl Laemmle, was rousted out of bed and dragged into Gestapo headquarters for interrogation. British-born Phil Kauffman, head of Warner Bros.’ branch office, was set upon on the streets of Berlin and beaten up by brownshirts.

Neither the Hollywood studios nor the motion-picture industry’s official arm, the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, offered a united response to the Nazi actions. Warner Bros. and Universal pulled up stakes early and got out by 1934. MGM, Paramount, and Fox (after 1935, Twentieth Century-Fox) stuck it out, transferring their Jewish personnel to other countries, firing the local Jews, and substituting more racially suitable employees.

Thus, when the Nazis annexed Austria, the Hollywood studios braced for a recurrence of Berlin in 1933. “Expect usual number of anti-Semitic moves directed against motion picture business,” Variety told its readers, the matter-of-fact tone indicating that a policy once shocking had become utterly predictable. “Of course [the studios’] offices have reduced their staffs considerably and dismissed all Jewish executives,” the trade weekly Motion Picture Herald noted in an on-site dispatch filed by a brave stringer who, understandably, preferred to forgo his byline. “Within days of the annexation, nearly every Jewish exhibitor, particularly the owners of the first run theaters, was taken into custody on trumped-up charges of being in arrears on tax payments. The notice ‘Under Aryan Management’ or ‘Under the Commissariat of the Reichsfilmkammer’ is seen at the entrance of almost all cinemas owned by hitherto Jewish exhibitors.”

Among the motion-picture personnel caught in the vise of history was Dr. Paul Koretz, Twentieth Century-Fox’s man in Vienna. An especially valuable company asset, Koretz was a prominent attorney regarded as the leading expert on international copyright in the film industry. Since the 1920s, he had served as the personal representative of William Fox and an attorney for Fox Film, though he also freelanced his services to the other studios. It was Koretz who arranged for the German Expressionist genius F.W. Murnau to come to Hollywood to direct Sunrise (1927), who negotiated Hedy Lamarr’s MGM contract, and who convinced playwright George Bernard Shaw that Pygmalion had motion-picture potential (a grateful Shaw dedicated the screenplay to him). Famed for his air-tight contracts, Koretz established enduring guiding principles for the acquisition of literary properties and also the rights to broadcasting films. (Perhaps the best proof of Koretz’s canny farsightedness was that his contracts sewed up broadcasting rights for motion pictures 20 years before television was perfected.) Most significantly, Koretz was responsible for negotiating Fox’s acquisition of the German Tri-Ergon optical sound system, the sound-on-film system that became the industry standard.

Of course, international reputation and professional accomplishments were no protection for a Jew in a nation that was now part of the Greater Reich. So, Koretz’s employers at Fox—in some ways, more alert to the dangers than Koretz himself—moved with dispatch to facilitate his escape. The story of Koretz’s extraction from Vienna is chronicled in a remarkable letter, dated May 10, 1938, written by Robert Bassler, who headed up Twentieth Century-Fox’s story department in London. Bassler’s letter was graciously shared with me by Sharon Leib, great-granddaughter of the motion picture pioneer Sol M. Wurtzel, who worked at Fox from 1914 until 1949; it tells a tale more suspenseful and dramatic than any scenario that the executive reviewed in his London office.

***

A former editor for the Reader’s Digest, Bassler had been sent to London by Fox in 1936. It was a cushy assignment, requiring first-class travel to the studio’s branch offices across the continent. Bassler was soon known by name by porters and hotel managers in every major capital in Europe.

In early March of 1938, mere days before the Anschluss, when the newspapers and radio were full of ominous news and the tension throughout Europe could be cut with a knife, a concerned Bassler traveled to Vienna to size up the situation on the ground. He arranged to have lunch with Koretz in the doctor’s “delightful apartment on the Ringstrasse,” the grand boulevard encircling the inner city. Also in attendance was George Marton, a well-known literary agent in Vienna, whom Bassler described as “a very smart young Hungarian.” The three men “argued about what was best to do.” Reading the signs, the Sorbonne-educated Marton was determined to flee to Paris immediately. Koretz told Marton that “he was crazy, that nothing could possibly happen, that Mussolini wouldn’t let Hitler get away with” grabbing Austria, ostensibly an Italian sphere of influence. In retrospect, but perhaps only in retrospect, it seems amazing that Koretz—a sophisticated and well-traveled attorney in possession of one of the sharpest legal minds on either side of the Atlantic—could be so blind to geopolitical realities that he still hadn’t realized that Mussolini was very much the junior partner in the Axis alliance, and so oblivious to the menace lurking on the doorstep. (Marton was indeed smarter. He ignored Koretz’s advice and escaped to Paris.)

Looking back two months later, Bassler ruefully reflected on the missed opportunity. He also mourned for a nation that no longer existed. “In three weeks there was no more Austria, and we were making frantic efforts to get Koretz out,” he wrote to Harvey Klinger, in Fox’s New York office. At the Foreign Office in London, Bassler obtained the necessary visas for Koretz, his wife, and the couple’s two daughters. Everything seemed in order, but then all went silent from Vienna. The only communications Bassler received from Koretz were “very brief letters, quite guarded in their phrasing.” Anxious for Koretz’s safety, Bassler decided to act. “I finally could wait no longer, so I wired [Koretz] I was coming and hopped on the Orient Express.”

‘He is a Viennese to his fingertips, and something in his stubborn Jewish soul kept him from running away.’

Bassler traveled by the Arlberg section of the Orient Express, a first-class-only ticket via London-Paris-Zurich-Innsbruck-Vienna. The romance of the trip and the wonders of the landscape where not lost on Bassler as he sped over the Austrian Alps, still snow-covered despite the late season. Yet the picture-postcard scenery was blackened with grim portents. “Every station was draped with Nazi flags, cut-out Swastikas, and signs saying, ‘Ein Reich, Ein Volk, Ein Fuhrer’ [“One State, One People, One Leader”—the Nazi motto] and celebrating ‘99.75% JA’ ”—a reference to the April 10 plebiscite held throughout Germany, including Austria, in which voters were invited to answer the question: Are you in favor of the Anschluss? The announced result: 99.75% “Ja.”

Bassler was in for a greater shock when he arrived in one of his favorite cities. “Vienna was changed more than I would have thought possible,” he shuddered. “I arrived the day after Hitler’s birthday [April 21, 1938].”

Bassler checked into his usual digs, the plush Hotel Sacher (“my favorite hotel in all the world”), where he was relieved to be greeted by the usual staff, though their once-voluble gemütlichkeit seemed to have vanished. “Everyone seemed less smiling and more solemn than formerly, but I told myself that was only my imagination.” It wasn’t. After phoning Koretz and arranging for a meeting an hour hence, Bassler slipped into the hotel bar for a drink. “Then I knew it was not my imagination.” The amiable, bustling bar, once lively with smart Viennese women sipping coffee and young couples chatting happily, was nearly deserted. “I had a Martini and sandwich and departed hurriedly for Koretz’s.”

Koretz lived in an ornate building at Stubenring 6, directly across from the Ministry, prime real estate in the center of town. Formerly a sleepy administrative building, the Ministry was now buzzing with activity. Military motorcycles sped in and out and brown-shirted storm troopers were everywhere. “Temporary cloth signs were hung over doorways indicating various new departments of the German government.” The Koretz family had only to look out the window to see their beloved city transformed into an outpost of the Third Reich.

“To say that I found the Koretz household in an anxious state is understating it,” Bassler wrote. “In order to avoid being forced by Storm Troopers to wash the sidewalks or perform other humiliating menial tasks, none of the family was appearing on the street any more than was absolutely necessary to obtain food and the general necessities of life, and even mild Mrs. Koretz had been prevented by a Storm Trooper from buying meat at a Jewish shop.”

Despite the Nazis in the streets and the terror in the air, Koretz still failed to understand that his world had fallen apart around him. “I learned that the Doctor had delayed their departure so long because he still had hopes of getting a visa which would permit him to return as well as to leave,” reported Bassler. “He is a Viennese to his fingertips, and something in his stubborn Jewish soul kept him from running away.”

In the apartment with Koretz was C.A. Steinhaeusser, a noted banker. Steinhauesser’s partner, the 78-year-old Viktor von Ephrussi, patriarch of the most famous banking family in Austria, “had just been put into a concentration camp because of some suspected relationship with the hated Rothschilds.” [Von Ephrussi was in fact related to the Rothschilds by marriage; he managed to escape to England in 1939.] Von Ephrussi’s disappearance was not unusual. “Every hour new stories are told of the fate of friends you haven’t heard of for a few days, and don’t dare visit.” More as a diversion than anything else, Bassler complained of a carbuncle on his foot that had developed on the train during his trip. “Characteristically, in the midst of all their troubles, nothing would do but a doctor for me, and a little guy with Van Dyke whiskers and a black bag appeared forthwith and treated my ailment much more skillfully than my English physician.”

With the family “worn and frazzled,” Bassler left early and walked back to his hotel along the Ringstrasse. It was an eerie stroll with “military cars zipping about, steel-hatted guards goose-stepping before the Bristol and Grand Hotels, red-and-black bunting flapping everywhere and more soldiers than I have since Washington in 1918,” when festive parades marked the end of the Great War. The militarization of Vienna was complete. “Brown uniforms, black uniforms, all sorts of different uniforms, some striding arrogantly on business, other[s], boys practically, sheepishly eying the pretty prostitutes on Kärtnerstrasse.”

Back at the Hotel Sachar, Bassler spent a fretful night trying to shut out the din outside his window:

All night the quiet was broken by shouted orders of marching troops, popping of motorcycles, and clop-clop of cavalry. About 1:30 I heard someone, undoubtedly a Jew, repeating a phrase after someone else who gave it to him in rasping tones. I craned as far as I could out of my window but I couldn’t see them, though the scene was all too easy to visualize: some poor Jew, hurrying home through the dark streets, stopped by a blustering, perhaps drunken Storm Trooper, forced to say, again and again. “I am a lousy Jew, I am a lousy Jew.”

The next morning—April 22—Bassler arrived at Koretz’s building just as Koretz was stepping out of a cab. In his hands, he clutched the family’s passports. “I’ve got it!” he exclaimed, meaning the precious exit visas. Up in Koretz’s office, he shared the good news with the family. The doctor also told Bassler one of those odd, counterintuitive anecdotes about life under Nazi rule:

[Koretz] has been for many years a close friend of a German who is a Nazi and is now Commissioner of Police in Vienna [Gestapo chieftain Franz Joseph Huber, who survived the war, avoided conviction for war crimes, and died peacefully in Munich in 1975]. Through him, the doctor has got a visa permitting him to return [to Austria], the only such visa which had been granted up to that time to a Jew.

Koretz had other friends in official police circles who also remained loyal: “In telling how simple policemen came in of their own volition and testified that the Doc was a good guy, he gave way to emotion for the only time in the whole business and wept.”

The departure date was slated for Sunday, April 24. Bassler’s train ticket back to London took him through Paris, but since the Koretzes had no French visa, the family had to travel through Germany. Bassler changed his ticket so he might accompany the Koretzes. Dr. Koretz “seemed to want me to go with them,” he said, “although all I could really contribute was moral support.” Though Bassler diminishes the gallantry of his decision, it showed real bravery, as not even American citizens were immune from the whims of Nazi thugs.

The family spent Saturday packing up the possessions of a lifetime, making the anguishing decisions of what to take with them and what to leave behind. Bizarrely, again, a member of the Gestapo performed an important service for the Koretzes:

Another friend of the family is now a member of the Gestapo, and after Mrs. K. and the girls had packed every trunk in sight, he told them it would not be safe for them to take so much, and limited them to two bags per person.

The next morning when Bassler arrived at the apartment to go with the family to the train station he found “that Mrs. K. and the girls had multiplied four by two and got 15.” Koretz, furious, left the apartment to fume in the lobby, leaving Bassler “sort of holding the bag,” he joshed. Bassler did his best to help with the unpacking and repacking. “Hats, underwear, etc., were flying about there for a while, but finally we had eight bags ready to go.”

It turned out the lack of a French visa was a stroke of good luck. “The journey through Germany was twenty four hours of suspense, because so many stories are told of the difficulties of Jews crossing the border,” Bassler wrote. “But going via Germany was a good gag—most refugees try to get directly out into Switzerland and get caught. They never even looked at us at the border.” Not that there was any elation on board the train to freedom. “The toughest part of the trip was the beginning, when they had their last glimpse of the Schönbrunn [Palace] as the train passed through the outskirts of Vienna.”

A few weeks later, safe in London, the family was adjusting to a new life. “Dr. Koretz and his family are settling down rapidly in London, and we are formulating plans day by day to enable him to continue his legal work efficiently from here, and to maintain our joint contacts in Europe,” wrote Bassler at the end of the ordeal. “It is really amazing how courageously he and his family have faced the necessity of carving out a new life for themselves.”

By 1940, Koretz and his family had made the move to Hollywood, where he continued to work for Fox, and later for MGM, where he represented Louis B. Mayer for some 25 years. But even in Hollywood the Koretz family could not totally escape the nightmare of the Third Reich. Son Frank, a graduate of Oxford and Columbia, who planned a career in law, like his father, was killed in action in France in 1944.

For their parts, both Bassler and Harvey Klinger went on to long and successful careers in the motion picture industry. Klinger worked for Fox in the story department for decades, securing the studio such properties as Planet of the Apes (1968) and The French Connection (1971); he was also a popular novelist in his own right, specializing in mystery and detective stories. Bassler returned to Hollywood when the war in Europe broke out and moved up the studio hierarchy to become a prolific producer at Fox, wrangling a varied slate that included His Gal Sal (1941), The Black Swan (1942), and The Snake Pit (1948). He ended his career in the medium Koretz had anticipated, producing episodes for television’s M Squad (1957-60) and Route 66 (1960-1964).

After the decline of the studio system in the 1960s, Paul Koretz retired and lived quietly—“in relative obscurity,” as his obituary in the Los Angeles Times put it. He died in Hollywood in 1980 at age 94.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Thomas Doherty, a professor of American Studies at Brandeis University, is the author of Hollywood and Hitler, 1933-1939 and Show Trial: Hollywood, HUAC, and the Birth of the Blacklist.

Thomas Doherty, a professor of American Studies at Brandeis University, is the author of Hollywood and Hitler, 1933-1939 and Little Lindy Is Kidnapped: How the Media Covered the Crime of the Century.