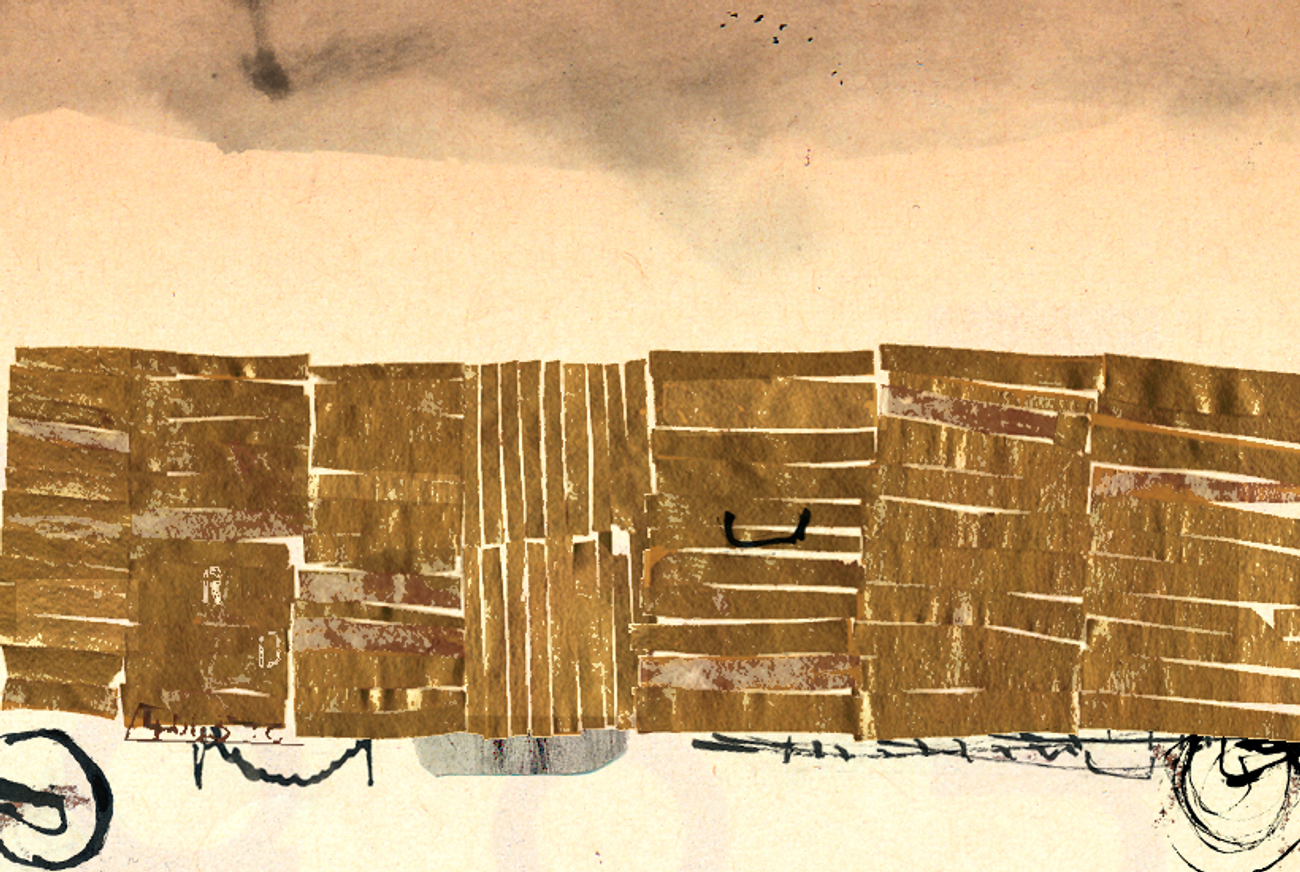

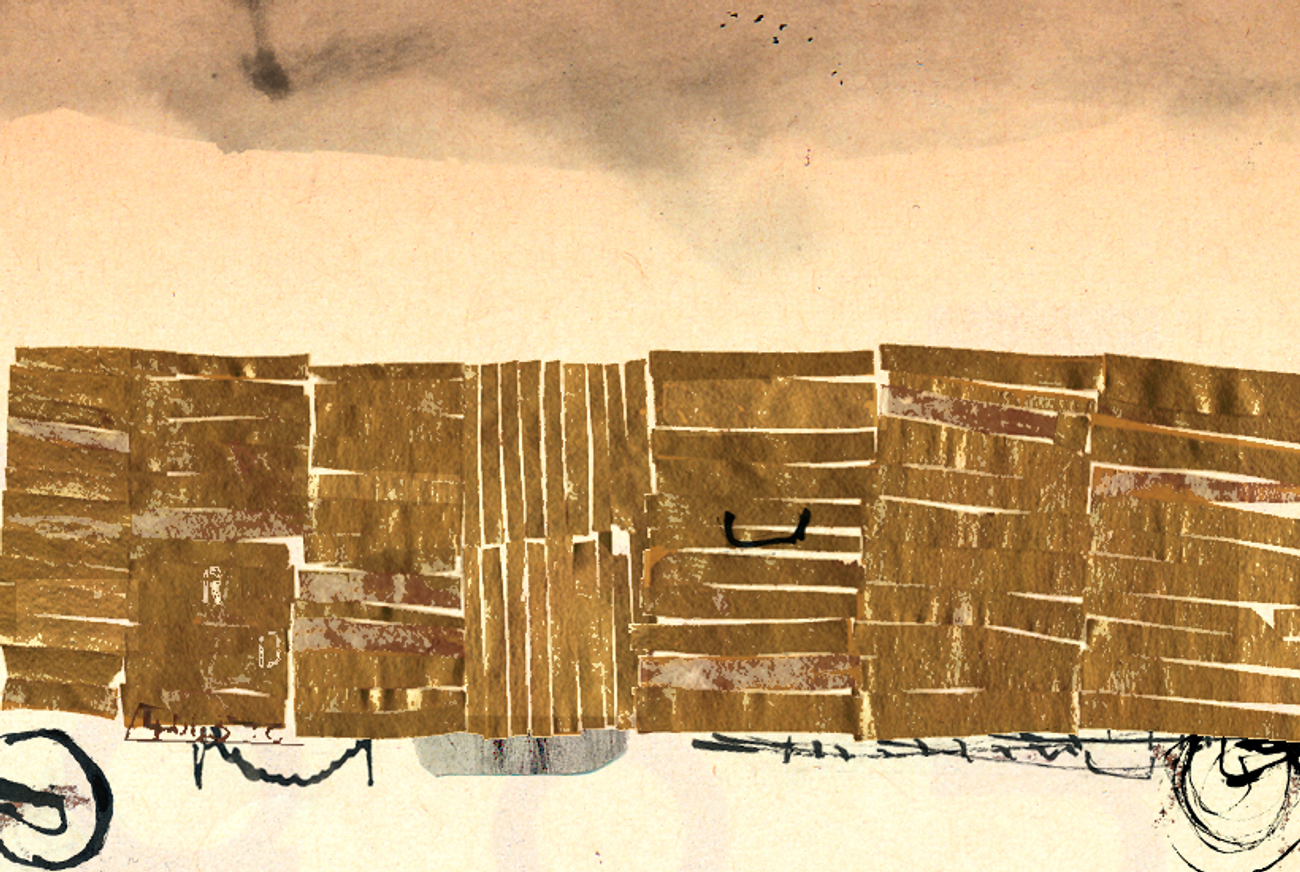

In the Boxcar

Seventy people, speeding into the unknown

We were about seventy people in the boxcar speeding into the unknown. I say “about” seventy, because none of us was able to come up with an exact number, although many had counted. This compulsive counting was a means of not counting the members of one’s own family, both those present in this boxcar and those who had already perished; or was it a way of escaping the thought of what was to come after we reached our destination; or perhaps it was merely a pastime?

The floor of the wagon shook. The people sitting there swayed to and fro like sheaves in the wind. There were children amongst us, there were babies miraculously saved from previous deportations—exhausted, tiny bundles of life, bathed in perspiration, wriggling and squirming in the protective arms of their mothers, crawling up their mothers’ shoulders. They wailed, gasping, trying to inhale with open mouths more air than was possible. How could a world without children continue to exist?

I thought of the twenty years of my life, unable to grasp them whole with my mind. I too felt like a baby in a diaper, miraculously saved—for this trip.

There were other sounds beside those coming from the mouths of the little ones. I could hear the indistinct mumbling of the adults and the groans of the sick, the sounds of prayer, and the anxious sighing of grandmothers, as well as the surreally ordinary conversations of the young. There was the strange sound of my own voice. And there was also the occasional sudden silence bombarding the eardrums, tolling in my head with a thousand bells. There was the near-darkness of dusk during the day, and the pitch black of the night.

Abrasha, my former teacher and present friend, sat beside me, trying to explain to me why no one was able to come up with the exact number of people present in the boxcar. “Counting heads is dangerous,” he said. “Counting an exact number of people is bad luck. That’s why superstitious Jews count, not one, not two, not three…”

The small boxcar window was covered with a grating of barbed wire, like the window in a prison cell. It was located at the upper corner of the wagon, to the right of the sealed door. A dozen hands held on to the knotted mesh of wire separating us from the outside world. Amid the entanglement of fingers and wire, open human mouths poked out like the beaks of abandoned baby birds, waiting in vain for their parents to rescue them.

Every once in a while those by the window noticed someone standing on the platform of a station as we sped by. They shouted through the mesh of wire, “You, brother! Say, where are they taking us?”

“Where are they taking me?” The question echoed inside my skull.

People were squabbling for a place at the window. Everyone wanted to be near it; we all considered ourselves entitled to at least a modicum of fresh air.

Our group of fifteen consisted of friends who had hidden together with my family during the liquidation of the ghetto. We occupied the left corner of the boxcar. Among the men in our group was Gabi, the leader of our youth movement in the ghetto. I was glad that we had him with us. There was an air of authority about him. By his side sat his wife Sonia with their baby girl in her arms. Beautiful, black-haired Sonia looked like an oriental Madonna, fully conscious of her child’s approaching Golgotha. Her face was almost as black as her hair.

As the squabbling by the window continued, Gabi jumped to his feet. “Listen, people, there must be order at the window!”

Reluctantly, they listened to him. It had been clear from the start that Gabi’s was the voice of a born leader, and the wish for a leader at such a time was great. Gabi decreed that from now on we must take turns at the window, so that everybody would have an opportunity to breath the fresh air.

But those standing near the window pretended not to have heard Gabi’s words. When they were pushed aside by the next group of people, they pushed back and held on stubbornly to the window grating with their fingers, their eyes locked on the sky, which, chopped into small slices, was visible between the meshes of wire. When Gabi approached them, they scowled at him. However they eventually moved away, allowing the next group to snatch at the grating with their hands and inhale deeply. When their time was up, they in turn forgot that the precious place at the window was not theirs for good, and they too were reluctant to step aside. Gabi was forced to intervene again.

Finally, our group’s turn came to stand near the window. Papa noticed a man standing on the road which ran alongside the tracks. He thrust his hand out through the window grating and shouted at the top of his voice: “Hey, mister! Where are they taking us?”

The man called back. I could hear his voice faintly, but the wind carried away the words. Where were we being taken?

After a while we scrambled back to our place and sat down, squeezed in among rucksacks, valises, bundles, parcels. The next time our turn came to stand at the window, we did not move from our corner, which had become our last refuge, our last home. We had no energy left to elbow our way through the piles of bodies and pieces of luggage. It was difficult enough just to make it to the slop pail in the opposite corner, when it was absolutely necessary to reach it. We had left behind such sentiments as embarrassment and shame concerning our bodily functions, just as we had left behind many other habits of a civilized race.

The train’s ceaseless clip-clop, far from lulling our anguish, expanded it. Time—so threatening and so sacred—ticked away to the beat of the wheels, a rhythmic swaying of the pendulum on the face of a gigantic clock without hands.

Fear hammered in my temples. I could hear it in the whistling of the locomotive through the night, in the pooh-pooh-breath of smoke and steam spewing from under its belly. I was overcome by an unbearable fatigue. A powerful emotion swept over me of tenderness for my parents, for my boyfriend Marek, for my sister Vierka, and my dear friend Abrasha. I felt a tenderness for our entire “family of fifteen” and for all those present in the boxcar—as well as for my own self. I felt a tenderness for the magnificence of the world which was receding, running backwards, rushing away from me, and sinking into the void beyond the horizon. A tenderness even for Him in the heavens, no matter whether He was there or not.

It seemed to me that not only were we experiencing the horror of these hours, but that the entire universe was experiencing them along with us, that everything that existed in this world was present with us in this boxcar. The ceaseless whistling of the locomotive through the night mingled with the lilt of the pious Jews reciting the psalms. Wrapped in their white prayer shawls, they swayed back and forth to the rhythm of the wheels and the rhythm of their prayers. Their tearful Shma-Isroel mixed with the harsh clanking sounds of the chains linking one boxcar to the other. It mixed with the huffs and puffs of the locomotive and with the howl of the wind outside, a howl that sounded like the ram’s horn when it is blown on Yom Kippur.

The pious Jews did not interrupt their recitation of the psalms, not even when Gabi, as if seized by a dybbuk, rose to his feet, climbed onto his rucksack so that everyone could see him, and holding on to the ceiling of the wagon with his hand, projected his loud resonant voice into every corner of the boxcar. “People, don’t give up hope!” he shouted. “The hour of liberation is approaching! The Germans have suffered defeat on all fronts!” Drawing on the information he had gleaned from the illegal radio he listened to in the ghetto prior to our deportation, he gave a detailed account of the situation on the battlefronts and of the intricate diplomatic negotiations, which proved that the end of the war was at hand, maybe as soon as the approaching day.

He seemed to have kindled a ray of hope in the hearts of his listeners. Someone called out an optimistic slogan. Others embarked on a philosophic discourse about the eternal values of Judaism, about the moral heritage of past generations, about feats of heroism in our history during the times of the Hasmoneans and the Maccabees, the proud acts of defiance during the Inquisition, the courage of Jewish martyrs dying for kiddush-hashem. Gabi awakened a sense of self-respect even among the cynics and skeptics in the cattle car. He kindled in us a sense of solidarity with all those trapped in the shackles of evil all over the world. His words expanded the walls of the stifling boxcar.

But Gabi’s words did not reach the ears of those reciting the psalms, nor of those holding children in their arms. Nor did his own Sonia listen to him. She was oblivious to what was going on around her. Leaning her back against the shaking wall of the boxcar, she bent over the baby in her lap and did not change her position.

And there were a few who mocked Gabi. A man with a crooked shoulder screwed his index finger into his temple and barked at Gabi sarcastically: “You are coocoo, young man!” he scoffed to the people sitting next to him. “Listen to this hummingbird, humming so sweetly! Just listen to him!” He cracked the knuckles on his bony hands, his wrinkled face expressing sardonic amusement.

A mousy little man, thin and hunched, accompanied Gabi’s speech with the slurping sound of crying. A long gray beard cascaded over his raised knees, so that nothing except the beard and his tiny wet eyes were visible. As Gabi talked the little man shook his body, mumbling, “From your mouth to God’s ears, woe is us! But the Almighty prefers silence to words, woe is us. That’s why He Himself keeps silent, woe is us. He is mute, woe is us. So please, young man, shut up and don’t be so smart.”

Papa turned his eyes to the weeping little Jew, then gave his sleeve a tug: “Mister, aren’t you by any chance a watchmaker? About twenty-three years ago, I bought two wedding rings from you…”

The little Jew shook Papa’s hand, and continued sobbing, “All the watches have stopped ticking, woe is us…”

We ate. Before our departure the charitable Nazis had allotted us half a loaf of bread each. The women spread white rags over their laps and busied themselves with the bread, thriftily cutting slices so thin from the half-loaves that they were almost transparent. Then they doled out the slices to the members of their families, saving the rest of the bread for a “black hour.” They had to be reasonable and prescient in order to outsmart the devilish machinations of fate.

I watched Abrasha as we ate, then transferred my gaze to my own mother, whom I had until then avoided looking at. “Everything will be all right,” her eyes seemed to assure me, just as they had when as a child I had lain sick in bed. She belonged to that particular type of mother whose love poured from her heart without restraint. She was an over-protective mother, annoyingly so. This had been a bone of contention between us. In my childhood, she would run after me with my half-eaten food, begging me to finish eating. She was forever afraid that I might catch a cold. “Put on your scarf! Slip on your woolen underwear! Don’t run! Don’t sweat! Don’t walk around barefoot!” She never abandoned her worries, her fears, and anxieties, trembling constantly over our safety, our health, our lives. Any wonder? It had been such a long day of danger, a danger lasting for generations. A Jewish mother was there to protect, to sustain her progeny. She was there to ensure the continuity of the race by insisting on living through her children, by living their lives. Such was my Jewish mother Binele.

I must have dozed off after our sham of a meal. The night dragged on. The smell of the overflowing slop pail in the corner mixed with the rush of the wind piercing the grating, filling our nostrils with both the stench of excrement and the fragrance of ripe fruit, of hay, and wilting leaves. The nightmarish hours of wakefulness were punctuated by the incessant whistling of the locomotive and its steamy smoky panting. Then a woman’s scream pierced the darkness. She spat a torrent of curses into the night, “May the day of my birth be cursed! May the day be damned when I brought children into this world!” Her cry became the signal for the other mothers to explode with curses of their own.

Other women burst into spasmodic wailing. They wrung their hands, pressing their children closer to their bosoms. The men, the children’s fathers, dulled, bewildered, mumbled something helplessly, or clenched their fists, or yelled at their wives to shut up, resisting as much as possible the urge to join the women in their lamentation.

I wanted to flatten the creases on Papa’s wrinkled face. I wanted to plant a kiss on each of his warm, honey-brown eyes, the eyes of a dreamer. He caught me looking at him and said loudly in order to make himself heard, “Don’t worry about me.”

“Don’t you worry about me either!” I shouted back.

“Everything will be all right,” Mama interposed.

My parents were leaning against each other, their bodies swaying in unison to the rhythm of the wheels. They gazed at my sister Vierka with an expression of such pain in their eyes that it gripped my heart. I wanted to say something silly to them to make them smile, but my mouth would not obey me.

There was finally a lull in the screaming. Mama said to us softly, “Don’t be afraid. They won’t separate us. We are all healthy, able-bodied adults. To the Germans a child over ten years is also an adult.” She beckoned to my sister Vierka to approach, and leaned forward towards us. “Remember,” she said with an ominous tremor in her voice. “We hold on to each other’s hands and we do not let go, whatever happens.”

I felt Papa’s hand on my head. Papa’s beautiful hand. I felt as if a flood of invisible tears were washing down my face. Where did I get the strength to hold back such a deluge of tears? I buried my face in my arms in order to hide my despair. Mama took my hand into her soft palm and held it tight. Papa’s hand on my head. The healing touch of Mama’s palm. I wished that this trip would never end.

The women in the boxcar continued their intermittent wailing. A few times Gabi stood up and went over to calm them. Mama leaned down to me: “Crawl over to Sonia and tell her that I still have two spoonfuls of sugar left. She can have them for the baby.”

I wiped my face and crawled over to Sonia. I touched her arm, telling her what Mama had said. She stared at me with the rage of a tortured animal. I realized then why Gabi was unable to endure for too long the sting of those eyes.

“What do I need the sugar for?” She shrugged, pointing to the baby, “Hear her snoring? I drugged her with poppy-seed broth.”

“Take the sugar,” I insisted. “You might need it later on. You never know.”

“I do know,” she snapped back. Her lips were as black as her hair. She again gave me that terrible look and indicated the lamenting mothers. “They also know.”

“Don’t lose hope,” I implored her.

A fierce scowl distorted her face, “You’d better shut up. What do you know? Have you ever been a mother?”

I squirmed and moved away from her.

The train began to slow. The chains linking the boxcars grated against each other with increasing frequency. The locomotive puffed and heaved as though it were running out of steam. Then it emitted a prolonged sigh and grew silent. The boxcar jerked back and forth, throwing the people backwards and forward. The overflowing slop pail in the corner of the wagon swayed and turned over, spilling its content onto those sitting nearby. Then it all came to a stop.

The sealed wagon door was unbolted and thrown open. The rush of frigid air struck us in the face. My head swam. Dazzling daylight blinded my eyes. “Aussteigen! Disembark!” Deafening bellows filled our ears. Dogs barked. The sound of many whistles. The whistling, once it started, never stopped.

We jumped out of the boxcar, just as the other wagons disgorged their human freight. Suddenly we found ourselves in a throng of thousands. Odd-looking men wearing odd-looking striped pajamas busied themselves among us, jumping into the open wagons. A nauseating smell hovered in the air.

As soon as our group gathered together on the crowded platform, Gabi grabbed the arm of one of the striped men. “Where are we?” he shouted, as though the other man were deaf.

“Auschwitz!” the other shot back. He shook off Gabi’s hand and climbed into our wagon, from which a number of sick people had not yet managed to disembark.

Gabi gaped at us in bewilderment. “Auschwitz! It can’t be… Impossible!” he gasped.

“Where is Auschwitz?” a frightened boy asked, raising questioning eyes to his father. The father shrugged, a stupid expression painted all over his face.

“Tell me, Mister,” someone from the crowd asked another of the striped men. “Is this still Poland, or are we in Germany already?”

“Neither Poland, nor Germany.” The sweaty man pointed to the heavens. “This is Himmelland! Put down your luggage, all of you! Put all your bundles and valises on the ground to your right!” He and the other striped men started snatching suitcases and sacks from people’s hands and piling them up at the edge of the platform.

Gabi mumbled something. We stared at him. His lips trembled. His face was chalk white. His small gray eyes had acquired a reddish cast, as if the rising sun were reflected in them. He threw his arm around Sonia and the baby.

All the boxcars had spat out their contents at last. The open wagon doors looked like the countless gaping mouths of a monster again waiting to be fed.

A brigade of SS men, whips in hand, marched towards us, dogs on leashes at their side. The whips swished through the air above our heads. To the accompaniment of the barking dogs, the SS men spat out their commands and made order among the chaotic mass of people that stretched alongside the tracks. The men in the funny-looking stripes continued to plunge into our midst, grabbing packs, rucksacks, and valises from the hands of those who still clung to their belongings.

“You’ll get it back later!” one of the striped fellows promised a crippled young man who desperately pressed a small briefcase to his chest.

“But how?” The crippled young man wrestled with the striped man for his briefcase.

“Ask for the Himmelkommando, idiot!” The man in stripes finally tore the briefcase from the other’s arms, nearly toppling him over.

We had already discarded our hand luggage and before I could even look around, the rucksack was torn from my back, as were the rucksacks of the others in my group. Handbags full of family photos were pulled from the arms of the three mothers among us and flung onto a separate heap of papers, letters, photographs, and prayer books.

We were left with nothing but the remainder of the half-loaf of bread we had saved for a black hour. We tucked the bread under our arms, while clinging with convulsed fingers to the hands of our loved ones.

“Women and children remain here! Men move to the other side!” The order thundered once, and then again.

A sudden hush. The enormous open sky overhead looked as hollow as the inside of an empty bell. The rustle of loose papers scattered on the ground, the whisper of pages from the small psalm books fingered by the breeze. These sounds, so very faint, reached our deafened ears. But all we could really hear were the chilling words of the command, and the sound of the whistles.

The members of our group clung tightly to one another. We were like dots entangled in a knot, woven into a dense web of other knots, which all together made up the three thousand heads of the crowd. How could these knots of blood-relatedness, of devotion, of love be torn asunder? Mama held us frantically in the embrace of her arms, which seemed to have grown in length. Only Abrasha, attached to no one, hovered around us all, in a kind of dancing step, as if preparing to protect us, or, as if he were seeking our protection by trying to be included in our midst, even though we had not excluded him. Or perhaps he was just busy counting our heads? We were exactly fifteen! Did the Jews believe fifteen to be a lucky number?

“Men! All the men to the other side! Quickly! Women and children stay where you are!”

A cohort of SS men began mechanically tearing the reluctant men from their women and children. They did it in rhythm. “Los! Los!” Staccato-like. As though they were ripping up sacks and dividing them into strips; sacks, not people; not body from body, flesh from flesh, life from life; not like tearing limbs apart, but like cutting ropes that had become entangled. The faces of the SS men reflected no awareness that they were inflicting pain, not the slightest hint that this scene touched their humanity. Nothing. They were robots with stony faces. And yet these robots, so elegantly dressed in dazzling uniforms, with spotless white gloves on their hands, looked so shamelessly human. Did they belong to a new race, or were they the scum of the old one? What were they? Who were they? If they had hearts and minds, then what was going on inside them at this moment? It was of enormous importance to find this out. The fate of the entire world depended on it—although this was no longer any of our concern.

“Hold on to each other! Don’t let go!” My sister Vierka pleaded, trembling like a leaf. Her small face was so pale, so transparent, that the locks on her forehead looked black.

An SS man clamped his hand like a vise around Abrasha’s arm. He hurled him in the direction of the column of men which was forming at a distance across from us. Abrasha had a silly smile on his face as he waved goodbye, calling out something that we were too deaf to hear.

Gabi had already been torn from Sonia and the baby. Papa escaped the SS men’s notice and we held him for a little longer in our arms. When was he discovered and dragged away? I looked on. I saw. But I no longer knew how it happened. Consciousness stopped registering. Memory was obliterated. I stared at the column of men across from us and with blind eyes searched in vain for Papa and Abrasha amid the river of fathers, brothers, sons, and lovers.

Here, in the river of women and children, there was not a sound; no sighs, no sobs. The women had forgotten how to shed tears. Tears did not belong here.

“Forward march!” the SS men thundered, commanding the column of women to move. The silence grew so heavy, so loaded with tension that it seemed about to explode and shatter the entire universe. We shuffled ahead. In front of me Sonia stumbled along with the baby in her arms. Malka and Balcha supported her, while two women I didn’t know, a mother and her daughter, made up their row of five. Urine trickled down Sonia’s legs.

Mama and Vierka were on my left side, as were Hanka and Sarah. The morning breeze held back its breath. My heart pulsated on the tip of my tongue. It pulsated within the emptiness of the hollow sky. The 28th of August 1944 was a dazzling, sun-drenched day.

A tall barbed-wire fence appeared to our left. Beyond it, on the other side, we could see shadows in the shape of women. We could make out the sound of distant voices shouting at us, “Throw your bread over to us, you won’t need it anymore!”

“Don’t listen to them, they’re crazy.” A man in stripes waved his hand as he ran past us.

On our right, in the distance, stood the column of men. It had been stirring a short while ago, but now that the column of women had started to move, the men’s column froze as if paralyzed.

A group of extremely elegant SS men of superior rank, apparently wearing brand-new uniforms in honor of this festive occasion stood in front of a wide-open gate. Above the gate was a large wrought-iron sign in beautifully shaped letters which read, “Arbeit macht frei! Work makes you free.” And—was it possible?—we could hear an orchestra playing! Tangos. Jazz. Had it only now started to play, or had it been playing all along but we had failed to hear it? And this entire carnival, had it just started, or had it been going on for eternities? Had the SS men only now embarked on the selection—or had that too been going on since the day of creation? Massive chimneys popped into view in the distance ahead of us. Were they part of our hallucination, seen through eyes blurred by anguish?

We were moving ahead, five abreast. Sarah, her face covered with fever splotches, chattered to Hanka. “Hold me tight. Straighten your back and smile. Yes, smile. You must smile. I will also smile.”

Her red lips worked themselves into a grimace that resembled a smile. She thrust her head forward, intent on showing us her trick. During all this time Mama, Vierka and I had not exchanged a single word, nor did we dare to look at one other. Clasping each other so tightly that it hurt, we now faithfully copied Sarah’s smiling grimace.

Hanka scolded Sarah, “Don’t you realize that your back is bent? Lean on me as much as you like, but straighten up and don’t drag your feet.”

I fixed my eyes on Hanka and Sarah, because I could not bring myself to look at Mama and Vierka during those precious minutes. I was afraid that if I did, I might collapse. Mama held me so tight, that I could feel each of her fingers clawing into the flesh of my arm. She seemed so much taller than I, so much taller and stronger.

We were at the gate. Now we could see the orchestra inside, near the gate. The musicians wore striped pajamas. Were they men or women? This circus band seemed to be swimming towards us, coming ever closer, aiming at the head of our column. Our column—a snake sticking out a double-forked tongue, one of its tips turned to the left, the other to the right, one pointing towards the Gate to Life, the other. . .This particular snake with its line of shuffling women and children was a tongue stuck out at the lie that man was created in God’s image—unless God was the devil himself.

I could see women and children stumbling away from the head of the column. Then, suddenly, a green arm with a red swastika armband on it flashed before my eyes. A hand ever so carefully, ever so gently, pulled the baby from Sonia’s arms. The hand did it with such a light touch, almost affectionately, as if it were removing a soft pillow from Sonia’s hands. The baby girl, drugged by the poppy-seed potion that Sonia had given her in the train was sleeping with her tiny mouth open.

“Was? Wa-as?” Sonia stammered in German, forming screaming question marks with her empty arms. She stretched her hands out to the SS man, as if to a good uncle who had taken the baby for a moment to play with, to smack his lips at, to tickle under the chin and then would restore her to her mother’s arms. In fact, the SS man grew thoughtful, and made a movement as if he were indeed about to return the baby to Sonia.

The dashing, dark-haired SS man standing beside him inquired, “Was istden los?”

“Nothing at all, Herr Doctor,” the young SS man grinned. “But she’s very pretty, so let’s allow her to go with the baby.”

“By all means. But not today. The baby goes today. She will follow tomorrow.” The Herr Doctor smiled a jovial decisive smile.

In the blink of an eye, the baby vanished from sight. Sonia, unaware of what was happening, took a step backward, hitting against our row with the entire weight of her body. The young SS man caught hold of her and with an energetic thrust of his arm hurled her towards the open gate of the fence—towards life.

“We have nothing to be afraid of.” I felt Mama clutching my arm, as the green sleeve with the swastika armband flashed again before my eyes.

Every sound I heard during the second that followed, no matter how faint, every crease on the faces above the green uniforms in front of us, no matter how slight, every nuance of light and shadow was chiseled onto the blank screen of my brain, until it all came to a stop.

What happened to my sister Vierka? Why had the handsome young SS man pushed middle-aged Balcha towards the Gate of Life, while he shoved magnificent Vierka in the opposite direction? Twenty-two-year-old Vierka! Mama, of course, had to see to it that the mistake be immediately rectified. I could see her running after Vierka, calling her back. She raced towards the two SS men to explain it all to them. She was stopped by arms with swastika armbands. She yelled for Papa, “Yacov, Help!”

“Binele!” I seemed to hear Papa calling back.

Binele. Mama. She ran after Vierka. She ran after Vierka. She ran after Vierka. She ran away from me. She had always loved Vierka more than she loved me.

And so I lost Mama and Vierka. They dropped out of my sight, although the pressure of Mama’s fingers on my arm still burned into my skin. I saw myself staggering along with the other dazed women through the Gate of Life to the accompaniment of the orchestra. I came up right behind Balcha and Malka. Sonia, doubled over, her knees sinking, stumbled ahead as if at any moment she might collapse. She held onto her belly as though about to give birth, while her head was turned backwards towards the gate. From there came Sarah, pulling Hanka along in a kind of dancing step. So musical had we all become. Oh, how Mama and Vierka seemed to come dancing towards me, although I had lost them from sight. The imprint of Mama’s hand on my arm was flaming red. She was still holding me tight. I looked back at the gate, waiting for Mama and Vierka to join me.

We walked on and on through the Gate of Life. Such a long deep gate. It led from the wonderland of my childhood, from the Sabbath river Sambation at whose shores lived the happy little red Jews who had never known the Diaspora—to the land of the truest horror, where the river of blood of the little red Jews flowed on and on and on.

This excerpt from Chava Rosenfarb’s novel Letters to Abrasha is translated from the Yiddish by Goldie Morgentaler. It originally appeared in “At Home in Translation: Canadians Translate the World,” in the Autumn 2014 issue of The Malahat Review, and is reprinted with permission.

Chava Rosenfarb (1923-2011) is the author of the novels The Tree of Life: A Trilogy of Life in the Lodz Ghetto, Bociany, and Of Lodz and Love, and the short story collection Survivors. She was a frequent contributor to the Yiddish literary journal Di goldene keyt.