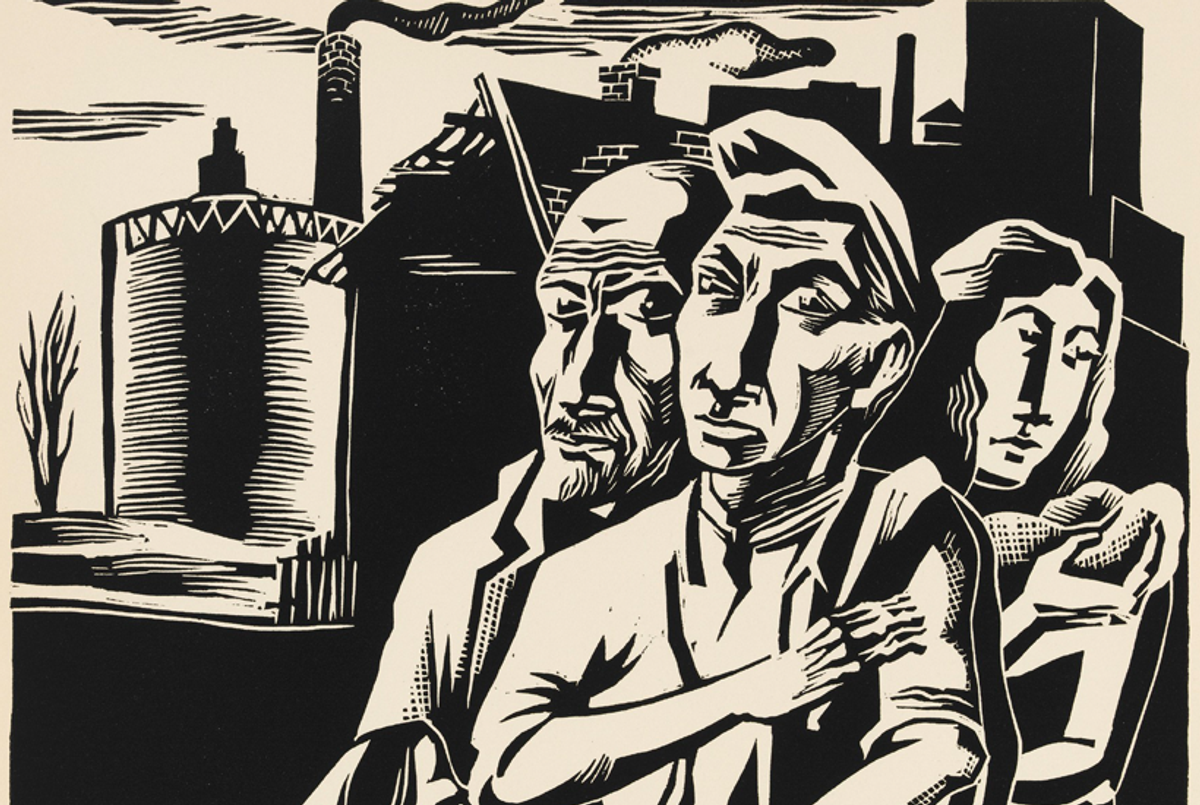

Entering “The Left Front,” the exhibition of political art from the 1930s, currently at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery through April 4, is to enter a foreign—but not completely unfamiliar—world populated by militant workers, capitalist fat cats, and impoverished slum dwellers. Breadlines alternate with demonstrations. Cities appear desolate, factories are monstrous. The French commune is the subject for a Marxist version of a Classics Illustrated comic book.

The prints and paintings on the gallery walls depict civil war in Spain and Jim Crow atrocities at home; there are continuous 16mm movies of May Day parades and rallies in New York’s Union Square as documented by John Albok, an amateur photographer and professional tailor born, like a significant number of the artists here, in the East European Jewish outback. Albok’s documentation of the 1937 parade is in color, but almost everything else is black and white—and not just because the lithograph is a favored medium.

The often painfully earnest art is skewed toward protest. Although there are no paeans to the Soviet Union or bouquets tossed at Comrade Stalin, radical politics trump radical aesthetics. Propaganda would hardly have been a dirty word for these artists, but modernist impulses are nonetheless present—if not, with the exception of the muscular precisionist Louis Lozowick, one reflecting the cubo-futurist Soviet modernism of the 1920s. Polish-born artist Henry Simon’s 1932 graphite drawings of the “Industrial Frankenstein” look forward to Allen Ginsberg’s vision of Moloch; another of his drawings, the smudgy, smoky 1937 “Bombing of Guernica” anticipates Picasso’s masterpiece, clearly a touchstone for politically minded American painters.

Only a few of the artists have secure spots in the modernist pantheon. There are two jazzy urban scene lithographs by Stuart Davis, a tireless organizer and blithe modernist, probably the best painter in the exhibit. The three great Mexican muralists—José Clemente Orozco, David Alfonso Siqueiros, and Diego Rivera—get token representation with lithographs or sketches. Significant art historical footnotes include Lozowick and the robust ashcan impressionist Reginald Marsh—the former represented by an image of industrial construction and a domestic still life, the latter by an etching of a breadline and a drab Chicago street scene.

It would have been possible to make a more artistically convincing exhibit of socially conscious, politically committed Depression-era American art, but “The Left Front” is more concerned with a particular sensibility than individual masters or masterpieces. Son of Bialystok, survivor of pogroms, Morris Topchevsky (the most represented artist in the show) does not appear to have many pieces in major American museums outside of the Block Museum of Art at Northwestern University, where “The Left Front” originated. Despite the delicacy of his water colors, the images are as blunt as their Titles: “Unemployed,” “Relief Shelter,” “Strike Against Wage Cuts,” “Company Violence,” “Down with Capitalism.”

***

“The Left Front” is heavy on Chicago artists. Some were employed by the New Deal’s signature program, the Work Projects Administration; many others, like Topchevsky, passed through the John Reed Club, an association of artists and writers devoted to the goals of the Russian Revolution and a culture of class struggle, supported by the CP until 1936.

The exhibit is underscored by the utopian sense art had a social-use value and should be available to everyone (prints being the most collectible form). In addition to lithographers, the key figures are largely makers of woodcuts and engravings, illustrators and cartoonists: party-liners Hugo Gellert (who boldly created a 60-print portfolio called Karl Marx’s “Capital” in Lithographs) and William Gropper; Carl Hoeckner and Rockwell Kent, two practitioners of the weird allegorical style that the show’s curators call “social mysticism”; Lynd Ward, the father of the graphic novel (recently escorted by Art Spiegelman into the Library of America), and the old-time Socialist Art Young. Prints are the high end. In addition to Ward’s 1932 novel Wild Pilgrimage, with its grim factory towns and graphic lynching, and the short biography of John Reed, One of Us, written by Granville Hicks, that Ward published with 30 full-page lithographs, there are copies of The Story of the Scottsboro [Boys] in Pictures” (1932), which originally cost two cents, and The Paris Commune: A Story in Pictures (1931), a pamphlet illustrated by William Siegel and sponsored by the John Reed Club, which went for a nickel.

Many of the pieces can best be understood as political cartoons to hang on your wall—if that’s the kind of décor you favor. Mabel Dwight’s skillfully rendered 1934 lithograph “Danse Macabre” has the personification of Death entertained by a Fascist puppet show with Hitler and Mussolini marionettes. Henry Sternberg’s 1937 “Steel Town” merges a hilltop factory with a church. Rivka Helfond’s 1937 lithograph “Miner and Wife” is a sort of unfunny parody of Grant Wood’s “American Gothic.” All of Boris Gorelick’s lithographs have a cartoony feel (he later became a background animator at Warner Bros.), but only a few works on display are overtly satirical. Elizabeth Olds’ 1940 silk-screen “Picasso Study Club,” which shows Picasso’s fans as Picasso creatures, is one; her “I Make Steel” with its outsized, glumly befuddled worker staring at fruits of his labor, would seem to be parodic as well.

Bernarda Bryson Shahn’s 1933 color lithograph “The Lovestonite” is laugh out-loud funny but only if you are a regular CP-history maven. Two conspiratorial men seated at a cafeteria table studiously ignore a blithely innocent third, as he waltzes by with his tray. The title tells us that they are Communists enraged to see an apostate follower of former CP secretary and heretical Bukharin-supporter Jay Lovestone dining at Stewart’s, the Sheridan Square cafeteria that would be characterized by Sherwood Anderson in The New Yorker as “the centre of proletarian high life.”

High life, sh-migh life: It cannot escape attention that, like Lovestone, many, if not most, of the artists in “The Left Front” are Jewish immigrants or their children. In an essay “On the ‘Jewishness’ of American Jewish Radical Artists,” included in the handsomely designed free broadsheet available at the show, historian Ezra Mendelsohn suggests that the most “Jewish” thing about these artists was “their commitment to universalism”—whether a revolt against parochial tradition or a prophetic vision of a new world. Both of these come together in the show’s most Jewish component—the 14 woodcuts by Chicago artists that were packaged together in 1937 as “A Gift to Biro-Bidjan,” a fundraiser for the Soviet Union’s official “Jewish homeland” opened to settlers in 1928.

Located in a remote, sparsely populated region of the Russian Far East, Birobidzhan was a Communist counter-Zionism (and in some cases crypto-Zionism) that had Stalin’s blessing. Jews constituted less than 20 percent of the total population when the region was declared a Jewish autonomous oblast (subdivision of a republic) with Yiddish its official language. In the mid 1930s, Birobidzhan was a crucial component of the Popular Front and thus the binding of American Jews to the Communist Party—although, as Lucy Dawidowicz recalled in her memoirs, the idea of Birobidzhan was attractive even to Yiddish-speaking non-Communists and, indeed, was supported by many progressive American Jews.

Some of the prints are undistinguished, if heartfelt, like Edward Millman’s blocky “Shoemaker” or Morris Topchevsky’s “To a New Life,” an image of a sturdy Jewish couple, books, blueprints, and a long-handled hammer in hand, leaving their ghetto forebears behind. Others are more striking: Raymond Katz’s “Moses and the Burning Bush” is an expressionistic composition based on sinuous flame-like forms. Bernece Berkman’s crazily cubistic “Towards a Newer Life” might have been titled in answer to Topchevsky’s print. (Berkman, who died in 1988 after a long career, impoverished, a squatter in her New York loft, is a figure worth rehabilitating.)

A number of the prints are frankly miserablist, like Louis Weiner’s gloomy “No Business,” Aaron Bohrod’s slum study “West Side,” or Mitchell Siporin’s grotesque “Workers Family.” Several are cautionary like William Jacobs’ Goya-gloss “Persecution” and Alex Topchevsky’s “Exodus from Germany,” but a few like Todros Geller’s ribbon of decorative vignettes “Raisins and Almonds” or Fritzi Brod’s “In the Workshop,” an unaccountably cheerful picture of sewing-work brought home, are almost celebratory.

The portfolio was completed in 1937, the same year that American Jews organized a selection of artworks to donate to a planned Birobidzhan museum. That was also the year when Birobidzhan’s leadership was rocked by the political terror that accompanied Stalin’s purge trials. Although shipped to the Soviet Union, the artwork never reached its destination—nor, presumably, did the portfolio. But I can easily imagine them hanging up in the Bronx living rooms of my 1950s childhood. The more positive ones might even be representations of the achieved Jewish homeland in Israel. The others are artifacts of the secular-minded, left-oriented Jewishness that may itself become a historical artifact.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

J. Hoberman, the former longtime Village Voice film critic, is a monthly film columnist for Tablet Magazine. He is the author, co-author or editor of 12 books, including Bridge of Light: Yiddish Film Between Two Worlds and, with Jeffrey Shandler, Entertaining America: Jews, Movies, and Broadcasting.

J. Hoberman was the longtime Village Voice film critic. He is the author, co-author, or editor of 12 books, including Bridge of Light: Yiddish Film Between Two Worlds and, with Jeffrey Shandler, Entertaining America: Jews, Movies, and Broadcasting.