For Judaism at Its Best, Look to the Muppets

More than just felt and googly eyes, the beloved creatures, returning to TV this week, are the perfect embodiment of our virtues

This coming Tuesday is a momentous day on the Jewish calendar, a day of awe, a day for all of us to congregate and communally ponder the ancient rituals and quiet beliefs that bind us to each other and to our faith. That’s because this Tuesday, a short while after Kol Nidre ends, the new era of the Muppets will dawn with a brand new show on ABC.

Call me shallow, but I’m more likely to tremble before Gonzo than I am to feel the holy spirit howling through my bones as I stand, besuited and weary, reciting ancient prayers. That’s because the Muppets aren’t just another fabricated bit of entertainment; they’re the googly-eyed embodiment of the best our bedraggled faith has delivered to the world and struggled so mightily to maintain for millennia. The Muppets, to put it crudely, represent the very essence of what it means to be Jewish.

I don’t mean this in the noxious, chauvinistic way that seeks the thick veins of bloodlines in every meaningful achievement. Jim Henson, the Muppets’ father, wasn’t Jewish, and none of his creations have anything overtly Semitic about them. But to see the Muppets interact is to come as close as we can to a world in which Judaism’s purest virtues are stripped of all their human imperfections and put to ideal practice, with hilarious and heart-warming results.

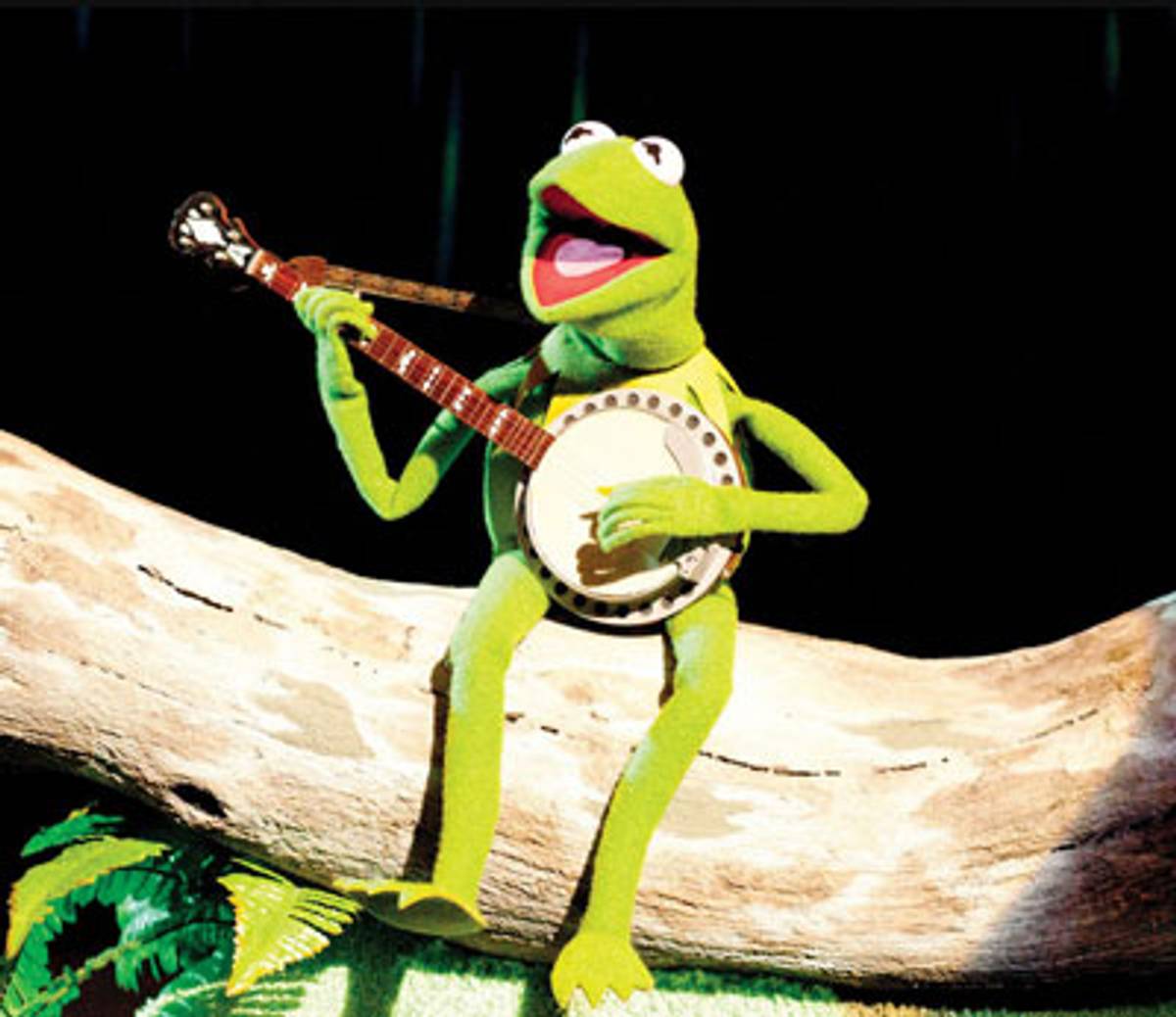

It begins at the top, with Kermit. Not since Moses was a leader burdened with the weight of shepherding such a stiff-necked flock: Just as the prophet had only to retire to the mountain for a few days for his people to fashion themselves a golden calf, so, too, does the wise amphibian find that a moment of distraction is all his charges need to unleash mayhem—the frog turns his back for a moment, and fish are tossed around, friends shot out of cannons, and certain egotistical pigs attempt to steal the limelight.

Others would’ve quit in despair, but not Kermit. Instead, he has the same dialogue with himself that Moses had with the Israelites. “The Lord,” Moses reminded the tribes huddled at the foot of Mount Sinai, “did not set his love upon you, nor choose you, because ye were more in number than any people; for ye were the fewest of all people.” Kermit came to a similar conclusion in “Bein’ Green,” his anthem about rising not despite one’s humble origins but because of them.

Like Moses, Kermit realizes the key bit of theology that sets him apart from Muppets and people alike: Nothing in life, he knows, is granted from above; if you want the divine promise to come true, if you want a land flowing with milk and honey or a killer variety show with very special guest stars, you’re going to have to work hard and earn it yourself. This is why Moses killed the spies who came back from Canaan and reported that the promised land was nothing but a hostile wilderness; they failed to see that the promise was in the people about to occupy the land, not in the land itself. Without faith and hard work, Canaan was just another Egypt. And without faith and hard work, the Muppets are just, well, lifeless puppets. This is why Kermit continues to insist on getting the gang back together for one more night on stage, even when the odds of success seem grim.

Which, of course, the odds often do: Like Jews, the Muppets are rarely without a nemesis, always shadowed by some villain questioning their right to exist. They are frequently canceled, but, somehow, they always return. This is curious not only because it defies the odds—you’d be hard-pressed to name another pop culture phenomenon that had managed to stay so relevant for so long—but also because once you settle down to watch the Muppets, you quickly realize that you are watching anything but a cohesive group. What, after all, do Bunsen Honeydew, the melon-headed and aloof scientist, and his assistant Beaker share with Pepe the King Prawn or the Swedish Chef? They have neither language nor ethnicity in common. They’re separated not only by the color of their felt but also by the content of their characters. But get them on stage, and somehow they all instinctively know how to play their roles in the big, collective play.

In part, that’s because the play has been going on for a very long time. Muppets, like Jews, are a traditional sort. No matter how deep their reservations, no matter how committed they seem to breaking out of the fold, all it takes is one tug at the heartstrings from the mishpocha and they’re right back where they belong. Virtually every Muppet movie begins with the gang all broken up, each swearing that they’ve outgrown their fuzzy days. Apply a bit of guilt, an appeal to tradition, and, like hardened atheists suddenly recalling their roots, they’re ready to sing the old songs and speak the old language anew.

The Muppets being both figuratively and literally unreal, they’re plagued by none of the inanities that consume so much of our time and vitality. While we bleed each other dry trying to decide precisely who’s a Jew, who’s a Muppet—a central point of the 2011 movie The Muppets—is almost a moot point: If you feel like it’s time to play the music, and it’s time to light the lights, if you’re willing to join the gang and share its fate for better or worse, you’re in. The Muppets have no institutions devoted to division. They’ve no federations, and no one jockeying for positions of power and influence. They’re chaotically committed to their vision, fiercely devoted to one another, and the closest thing we’ve got to a light unto the nations. Their new show may be terrible, but it will hardly matter; they’re not a product, but the better angels of our nature. They’re a way of life, our way of life, uncorrupted. Let’s pray we never abandon it.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.