Rothschild’s Luck; or, A Tale of Two Patrons

Newly translated fiction—a timeless fable about wealth and humility—from the Nobel laureate S.Y. Agnon, in time for Shavuot

I have heard that Rothschild once went on a journey. Along the way the wheels of his carriage broke; repairmen were called, but before the work was done the Sabbath arrived.

Rothschild saw he could not reach his destination before the arrival of the Sabbath, so he left his driver to watch the carriage, took his belongings, and set off for the nearest town. I have not heard the name of that place—if you would like to know, go and check the communal ledgers of those towns.

He arrived in town and entered the inn. He rented a room, dressed himself for the Sabbath, took his own prayer book, and went to the main synagogue—for the Rothschilds pray according to Ashkenazic custom, and in those small town synagogues one never knows what prayer custom he’ll encounter, whether Ashkenazic or Sephardic. This was different in the large synagogues where they maintained the customs of their forefathers, that is, to pray according to the Ashkenazic practice as was done throughout the generations.

He went and sat—not up front, not in the back, but in the middle. Not in the back, so as not to display false modesty; not in the front, because in a place in which one is unknown he shouldn’t put on airs. Rather, he chose a seat with neither fake humility nor haughtiness.

They sat and recited the Song of Songs and prayed the afternoon service. Upon finishing the Friday afternoon service everyone waited, without opening a prayer book to recite the Sabbath prayers.

Rothschild saw that the sun had set yet no one had started reciting the prayers for welcoming the Sabbath. He looked at his watch, he looked at the window, and he looked at the schedule on the wall. Rothschild asked, “The time to welcome the Sabbath has arrived, why aren’t we reciting the prayers?” They responded, “We are waiting for the Patron to arrive in synagogue, for we do not pray until he arrives, but he’ll surely arrive soon, since the sexton has already gone to get him.”

As they were talking the door opened and in walked the sexton, who called out, “Sha-a-a…!” informing one and all that the Patron was about to enter. Everyone answered, “The Patron is coming! The Patron is coming!”

Rothschild raised his eyes and saw a corpulent man, as wide around the middle as he was tall, dressed in silks and sables, with his face set toward the east.

The Patron reached the eastern wall at the front of the synagogue and sat in his place, all the while puffing and panting from his walk.

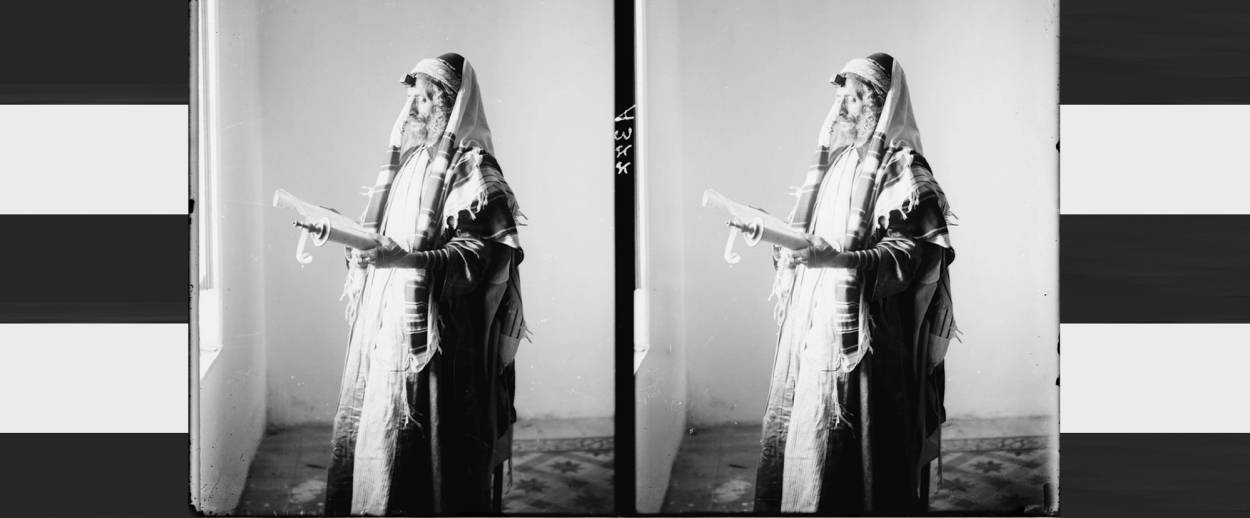

The prayer leader approached him, bowed, and asked, “What does your honor think? May we welcome the Sabbath?” The Patron nodded yes. The prayer leader retreated, with his face toward the Patron and his backside to the congregation, ascended the platform, wrapped himself in a tallit, and began the prayers.

After the prayers everyone pushed and shoved to approach the Patron, bow to him with awe and reverence, and wish him a Shabbat Shalom, while he nodded his head in affirmation as if to say the same.

Back at the inn, between the main course and the Sabbath songs, Rothschild asked the innkeeper about the man they had all waited for to begin the prayer service. The innkeeper looked with shock and surprise at his guest and said, “Well, he’s our Patron, of course! Haven’t you heard about our Patron, mister? He’s world renowned. I’m astounded that you haven’t heard of him.”

Rothschild asked what business this Patron is in. “What business is he in?!” replied the innkeeper. “That’s a tough question to answer. Were we to have all night I wouldn’t be able to list all of his dealings. In his right hand he holds the entire city, in his left lies life and death. If a person hasn’t bought his grave in full before he dies, then his children must purchase it—to say nothing of the headstone—from the Patron. From his little pinky hangs the business of the Great Synagogue and all its furnishings, to say nothing of all the pledges and donations that are made to it, as well as the communal estates and unclaimed inheritances, the charitable funds, etc., etc.”

The innkeeper grew agitated at his guest, who heard all this yet displayed no awe. But being a forgiving man he went on. “Even in his youth he was a great businessman, especially when it came to matters of charity. Before he was 9 years old he had established a welfare fund. Every week the other boys would bring him coins, and he would dispense them to the needy. He set up another charity—it didn’t have a name but its purpose was clear. As we know there are poor folks who never get a sip of wine. On Friday night they recite Kiddush over a loaf of bread, in the morning on two or three drops of schnapps, and Havdalah on a glass of tea. For the Four Cups at the Passover Seder they soak some raisins in water. The Patron’s good heart was aroused, and he asked, ‘Just because they are poor should they not drink wine? If not for Kiddush and Havdalah, then at least for the Four Cups of Passover.’ What did he do? He told his friends to get money from their fathers—some got, others didn’t. He wrote down in a ledger the amounts each brought every week, up until the time they’d each go off to get married. As for the wine, well, for an important poor person he’d measure out for the Four Cups, for an average beggar he’d pour just for the Cup of Elijah. And there were other charitable organizations he started in his youth, which he still manages, even though they cost more than they bring in. But let’s stop talking of money and focus on that which we are permitted to discuss on the Sabbath, as we sing in the hymn, ‘Your business concerns are forbidden; so too financial calculations./ Reflections are permitted and arranging matches for young girls…’ Well, when it comes to arranging marriages, shidduchim, for one’s children, not everyone is as lucky as our Patron!”

He poured a glass for his guest and one for himself, drank, and shouted LeChaim! LeChaim! “What was I saying? Oh yes, the marriages of the Patron’s sons and daughters. Five daughters and four sons, and he’s managed to marry off each of them. I’ll make do with telling you of the eldest daughters—for really, there’s no difference between the older and younger except the pedigrees of each son-in-law, certainly no difference in the dowries paid. As he gave to the older so he gave to the younger. Similarly with his sons, except of course the way of the world is to give larger dowries to the daughters, but he certainly gave many times more to his sons than their wives brought to the marriage—for he sought good pedigrees in their brides, and not mere wealth. I see the guest isn’t touching his glass? We manage with the schnapps the Patron doles out for us. Actually, the son-in-law of his second daughter’s husband holds the liquor franchise, not the Patron himself. But let’s get back to talking about the husband of the eldest daughter. LeChaim!”

“So, for his eldest daughter the Patron selected the son of a renowned family, whose forefathers had served in the rabbinate around the world, and the Patron arranged for this son-in-law to be appointed the rabbi of our own town. Some say he paid 10,000 silver guldens to the town to have the son-in-law appointed rabbi, aside from what he had to pay the matchmakers. Matchmakers for marriage, and matchmakers between rabbis and towns! Even the communal leaders benefited a bit from the Patron’s gifts. He would send them wine in silver bottles; the clever among them wouldn’t return the bottles, and yet the boy had not yet secured the rabbinic post. Suddenly all types of rumors and accusations were making their way to the authorities about our local rabbinate. What do such rumors have to do with anything? Well, just as we might ask about one Jew ‘informing’ on another, we might question the whole act of having the boy appointed—if a community needs a rabbi in the first place, why should it need to be bought off and bribed? Both questions can be resolved with one answer: When Moses ascended Mount Sinai to receive the tablets of stone, the Israelites made the Golden Calf, and when he descended he heard the sounds of war in the camp.

“But better than the rabbinic son-in-law was the husband of the second daughter, who had nothing to do with religious business and focused on this-worldly commerce. At first we thought he might be a secular, ‘enlightened’ maskil, since he wore his yarmulke tilted slightly to the left, but soon we saw he’s a real man and his head tilts only for the sake of money. His father-in-law leased the liquor tax-collecting post for him, and soon enough he was master of every drop in town. At first anyone who was able would bring liquor from elsewhere, for they said the Patron’s liquor is diluted with water. They put guards in the four corners of town, and anyone caught with imported liquor would be forced to buy an equal measure of our own brew, and he’d be made to drink it down on the spot. Fortunately our town’s liquor isn’t intoxicating! I see the guest isn’t listening?” “Oh, I’m listening,” replied Rothschild.

The innkeeper’s wife told her husband, “Tell the guest about the great feast.” He replied, “If you mean the dairy feast, I was about to tell it, but it seems to me the guest isn’t interested in hearing.” Rothschild asked, “What was the story?”

The innkeeper said, “The Patron secured a position as tax collector on meat for a different son-in-law. When his son was born, they arranged a huge feast for the day of the brit. The son-in-law’s father came, but he would not eat meat slaughtered out of town. So, they took all the meat that had been prepared for the feast and gave it away—a third to the priest, a third to the mayor, and the final third was split, half to the judge and half to the constable. They then arranged a new meal with only dairy foods. Such a meal may have been eaten on the very first holiday of Shavuot after the Torah was given on Sinai. Since then, no such dairy feast has been seen of this magnitude. For the three days before and three after not a drop of milk could be found in town—not even for pregnant and nursing women, nor for the infirm.”

In the morning Rothschild arose and went to the synagogue. After they recited the first introductory prayers, everyone sat and waited. Rothschild asked, “Why aren’t we continuing with the service?” They replied, “Your question indicates you’re an out-of-towner, for if not you’d never ask such a question.” They wished him well, and asked where he was from, and where he was going, and the like. What did Rothschild reply? Not every questioner is necessarily interested in hearing answers, and they were certainly of this sort. In terms of his question itself, they answered, “We were awaiting the Patron’s arrival. And it’s almost certain that he’ll arrive soon, since the sexton has already gone to call him. If so, why has he delayed until now? Either he’s drinking his tea, or his wife is looking for a clean handkerchief in honor of the Sabbath.”

While they were explaining these things to the guest, in walked the Patron, wearing sable, matching the shtreimel on his head, except that this was made of tail furs and velvet, while that is made of silk and skins. The sexton followed close behind, carrying the Patron’s tallit, prayer book, and Bible, while all stood in place until he reached his place and sat. The prayer leader approached him, bowed, and inquired if the time to start the prayers had arrived. The Patron nodded yes.

When it came time to remove the Torah scroll from the ark, they came to ask the Patron who should be honored with being called to the Torah for an aliyah. They also told him of the guest who was present and that he appears to be a man of stable means. The Patron glanced at the guest and replied, “If he’s neither a Cohen nor a Levi, you can call him for the seventh aliyah.”

When the Patron was honored with the third aliyah the congregation rose to its feet. The crowd parted as the Patron passed amongst them on his way to the Torah, his heavy tallit crowned with a silver sash and seam, with its tzitzit fringes trailing behind him, carried like a veil train by the sexton who was following. He ascended the platform and recited the blessings, to which the crowd answered with a hearty Amen! As he had gone up to the platform, so too he returned to his place, with the crowd at attention, parting the way as he passed back to his seat.

The guest was called for the seventh aliyah. In the prayer for his welfare following the aliyah, the deputy sexton leaned in to hear how much the guest would pledge. Said the guest, “Eighteen guldens times 18 times the net wealth of your Patron.”

Pandemonium broke out in the synagogue, whose members had never heard of such a sum. In truth, the world isn’t lacking rich Jews, as the Talmud relates about the three rich men of Jerusalem at the time of the Temple’s destruction, who had enough provisions in store to keep Jerusalem fed for 21 years during the siege. Even in latter generations, we’ve heard of wealthy Jews like Reb Mordechai Meisel in Prague, who did many charitable acts in his city and with his own money built the Great Synagogue, and a bathhouse, and paved Jews’ Street with stone, and paid for the weddings of many indigent brides, in addition to many other good deeds. Similarly Reb Izaak bar Yeklish, who found a treasure of gold hidden in his stove and built a large synagogue that was named in his honor. Even in our generation there are fabulously wealthy Jews, like Reb Moses Montefiore in London, and like Rothschild, and some say a new rich man named Baron Hirsch has been discovered, although it’s unclear if his name is Hirsch or if it’s Baron, or if Baron is his family name, as we’ve seen Jews with royal names like Koenig, Duchas, Herzog, Feurst, Graff, and even Kaiser. To say nothing of our own Patron—when suddenly along comes a guest and pledges 18 guldens times 18 times the net wealth of our Patron. This was particularly puzzling to the innkeeper, who liked to think of himself as a good judge of a guest’s worth, based on what he eats and drinks, how he conducts himself, etc., but this guest didn’t request any special meals, nor did he ask for more than his share of meat and fish and tzimmes. He behaved like a perfectly regular fellow, except for requesting a private room. In fact he saw the inn was empty of any other guests, and he could have had the big room with seven beds, or the smaller four-person room, alone to himself, without having to pay extra for a private room.

After the Sabbath ended the whole town came to the inn. I don’t mean to imply they rushed the concluding services, or skipped any passages of the prayers, but they abbreviated the extra hymns and hurried along to get to the inn.

So, immediately following Havdalah the whole town assembled at the inn. This one came with a pitcher, that one with a barrel, another carrying a vat or a sack or a pillowcase or a quilt emptied of its down. No one absented himself, and everyone came holding some receptacle, for our Patron is inestimably wealthy, so imagine how much money would be 18 times 18 that amount? As for the poor man, who has no pillowcase, he removed his yarmulke from his head and held it upturned before the guest. As the Talmud says, “Poverty follows the poor.” Every townsman will fill his pot with wealth, while this pauper will have to suffice with one small yarmulke full of gold. Yet still, we shouldn’t turn our noses up at a yarmulke full of gold.

While the town came to take its fill from Rothschild’s pledge, he was calmly circling his room reciting all of the songs and hymns for the departure of the Sabbath. They informed him that the whole town was waiting. He took a scrap of paper to mark his place in the prayer book and exited his room.

He saw the whole population with pots in their hands. He wished them a good week, and said, “I hear you’ve been waiting for me? To what do I owe this great honor?” They replied, “We’ve come to collect on your pledge made at the time of Torah reading.”

He told them, “That which I pledged I will pay, and my promises I shall keep. Be certain I won’t change my vow, not by a hair’s breadth, but I have a tradition from my fathers not to enter a deal without inspecting it first. So, please wait until I return home and I will send one of my men to check exactly how much is 18 times 18 times the worth of your Patron. In case you don’t believe me, here is my card”—printed with the name Rothschild on it. The townsfolk left and returned to their homes in peace, for they knew Rothschild was good for the money.

The town was split into vying groups, and each group was split into disagreeing factions, each debating what should be done with the wealth soon to pour into town. Even were they to make weddings for each orphan, clothe and shoe each schoolchild, purchase crutches for each cripple, bread for the hungry, a new fence for the cemetery, and grease the palm of each police officer, judge, and regional official, make wigs for each wife of the assimilationists so they shouldn’t go out to the market with uncovered heads—still there would be no end to the balance of funds left from Rothschild’s pledge!

While they stood debating what to do first and what to do before that, a new face arrived in town. No one knew who he was or why he’d arrived, but they guessed it must be Rothschild’s man.

How did they guess it was Rothschild’s man? For when the innkeeper boasted that just last week Rothschild himself had been a guest under his roof, the man didn’t seem surprised. And when the innkeeper told him news of Rothschild’s pledge, the man asked about the worth of the patron. When the innkeeper saw his words interested the man, he spun his tale of the Patron’s worth, to his own amazement and that of his guest. He was amazed at how much he had to tell about the Patron’s affairs; the guest was amazed at how much the Patron had.

Initially he felt that the guest’s questions were merely superficial. As he went on he saw the guest took note of each and every detail, asking him to repeat many points.

Just as the guest interrogated the innkeeper, so too with each person he met in town. Just as the innkeeper regaled him, so too did each townsman. At first they thought he wasn’t paying attention, but then from his questions they saw he didn’t forget a single word they said. Yet he inquired if there was any evidence for the tales they told, or if they were just gossiping, as is the habit of folk from small towns. Clearly he must be Rothschild’s agent, for if not, why ask about all the details? Obviously he was sent to assess the worth of the Patron, so as to determine what 18 times 18 times that amount would equal. For the Rothschilds keep their word, and if they pledge, then they pay—but just as they guard their promises so too they guard their pocketbooks. Not just from deals do the rich grow wealthy, but from watching that each penny should not be spent for naught. This is why Rothschild sent a special agent to assess the value of the Patron. Yet it’s still a bit difficult, for if he’s Rothschild’s employee why was his clothing nicer than that worn by Rothschild himself? If you’d like, I can answer with a quote from the Talmud, “The wealthy are cheap”—Rothschild, the richest of the rich, is frugal. Clearly this is so, for while at the inn he didn’t ask for extra food. If you prefer, it should be obvious: Rothschild is “clothed” by his good name, whereas his employee, who is after all merely one of his servants, needs fancy clothing, so none should disparage him. As the saying goes, “Where one is unknown, the clothing makes the man.” An important person needs to be distinguished in his dress, so if he comes to a place where none know him, he will be recognized and honored as an important man.

And so, Rothschild’s agent arrived and rented two rooms at the inn, the room Rothschild had taken, plus a spare room to hold all of the ledgers. Even though the inn was not large, it had five rooms, three downstairs, and two above. The upstairs rooms were rented by Rothschild’s man.

He sat and listened, and inspected, and examined the affairs of the Patron, those in town and those in other places, those from which he profited and those from which he derived other benefits—whether in cash or in gifts. Nothing escaped the eye of the guest. Even the communal and charitable affairs that the Patron stood at the head of. Even though he was busy going over the accounts, he warmly received each visitor, sat and talked over a glass of tea and bit of cake, showing respect for all, even those who came merely to chit-chat. Occasionally he would look suspicious, and sometimes he would ask, “Aren’t you exaggerating a bit?”

Thus he sat and listened, and inspected, and examined the affairs of the Patron—those that formed his main income, and those that were just “icing on the cake,” as well as those he was merely a figurehead for, such as the charities and communal funds and the like. There was no aspect of the Patron’s affairs that the agent didn’t inspect. Certain things didn’t require chasing after, for one fact would naturally reveal another. Other details made their way to his ear on their own, for if you listen carefully to a person’s conversation, you learn things you didn’t even think to ask about.

How long did Rothschild’s agent spend in town? A month, two months, or three or more? In all cases, Rothschild didn’t suffer any loss, for in the end he was exempt from paying the town even one penny. Ah, but he’d pledged 18 guldens times 18 times the net wealth of the Patron? It turned out that Rothschild’s accountant determined that the Patron didn’t even have one penny of his own, never had, and all his days he ate and drank at the community’s expense. His clothes and house were paid for with communal funds. Everything! Him, his wife the Patroness, their sons, daughters, sons-in-law, daughters-in-law, grandchildren, the nursemaids and manservants! Similarly the fancy feasts he would make, whether of meat or dairy. So too the bribes and gifts for the non-Jewish officials. All the money was brought from public funds, belonging both to the living and the dead. The living? These were monies from taxes the Patron had imposed. The dead? The costs of burial plots and headstones paid in full by anyone who needed one. The living? Pledges and vows, charity boxes and communal estates and unclaimed inheritances. The dead? Their children in America sent money to the patron to distribute to the poor in their memory. And even vacations at the spa that he and his wife and children took each year were paid for with public funds.

We see that wealth brings benefit to the rich, for merely being thought of as rich is a good omen for making a living. This fellow, who was merely presumed to be rich, ate and drank, growing a proper double chin, living the good life all his days—how much more so a truly wealthy man like Rothschild, whose luck is steadfast in each and every business deal, including in our story of this Patron? For he pledged 18 guldens times 18 times the net wealth of the Patron, yet in the end he didn’t need to pay up even one penny.

From this we learn that a person shouldn’t rely on what others think, even should the whole world say such-and-such about So-and-So; one must examine things for himself. Rothschild, who checked it out, was off the hook to pay. What would you have done in Rothschild’s place? You would have relied on what others said, and you would have lost.

Translated from Hebrew by Jeffrey Saks. For more on this story click here. Saks is the founding director of ATID. This original translation is forthcoming in a new anthology of Agnon’s short stories, Forevermore: Stories of the Old World and the New, edited by Jeffrey Saks, to be published by the Toby Press as part of its S.Y. Agnon Library, featuring the writing of the Nobel laureate in new and revised English translations. Saks’ courses given at the Agnon House in Jerusalem are broadcast at WebYeshiva.org/Agnon.

Shmuel Yosef Agnon shared the 1966 Nobel Prize in literature.