The Lost and the Saved

A photographic journey in search of an Israeli family she never knew she had

I woke as the airplane landed in Tel Aviv, where I was about to open a dark chapter of my own family history. It was a quest that began several years ago with an email from a stranger. In a warm introduction, this man, who called himself Nelli, wrote that he had been searching for me for years. We were, he said, not only both professional photographers, but cousins—related through our grandparents, who were brother and sister—and that his grandfather migrated to Mandate Palestine, while my grandmother found her way to America. He said his full name was Emmanuel—a tribute to our great uncle, the third sibling that our respective grandparents had left behind, and who eventually perished in the Holocaust.

I had no idea about any of it.

For all of my life, I was denied this information. I was told by my grandmother Becky, reluctant to speak her entire life about those early years in Horodenka, that her siblings went to Palestine by ship, some of them walking on foot part of the way from southwestern Ukraine. There was never a mention of her oldest brother Emmanuel. Very little was spoken even about her own father and mother.

Was my own grandmother to blame? Was it her reluctance to share with others, including her immediate family, the worst most painful memories of her past? Was the need to assimilate into the American way of life in part to blame? Any family members who could possibly know the truth were now all deceased. Would my own life have been different had I understood that my family, in fact, had lost members, in one of the most savage events in modern history? Or that we—that I—had a root in Israel?

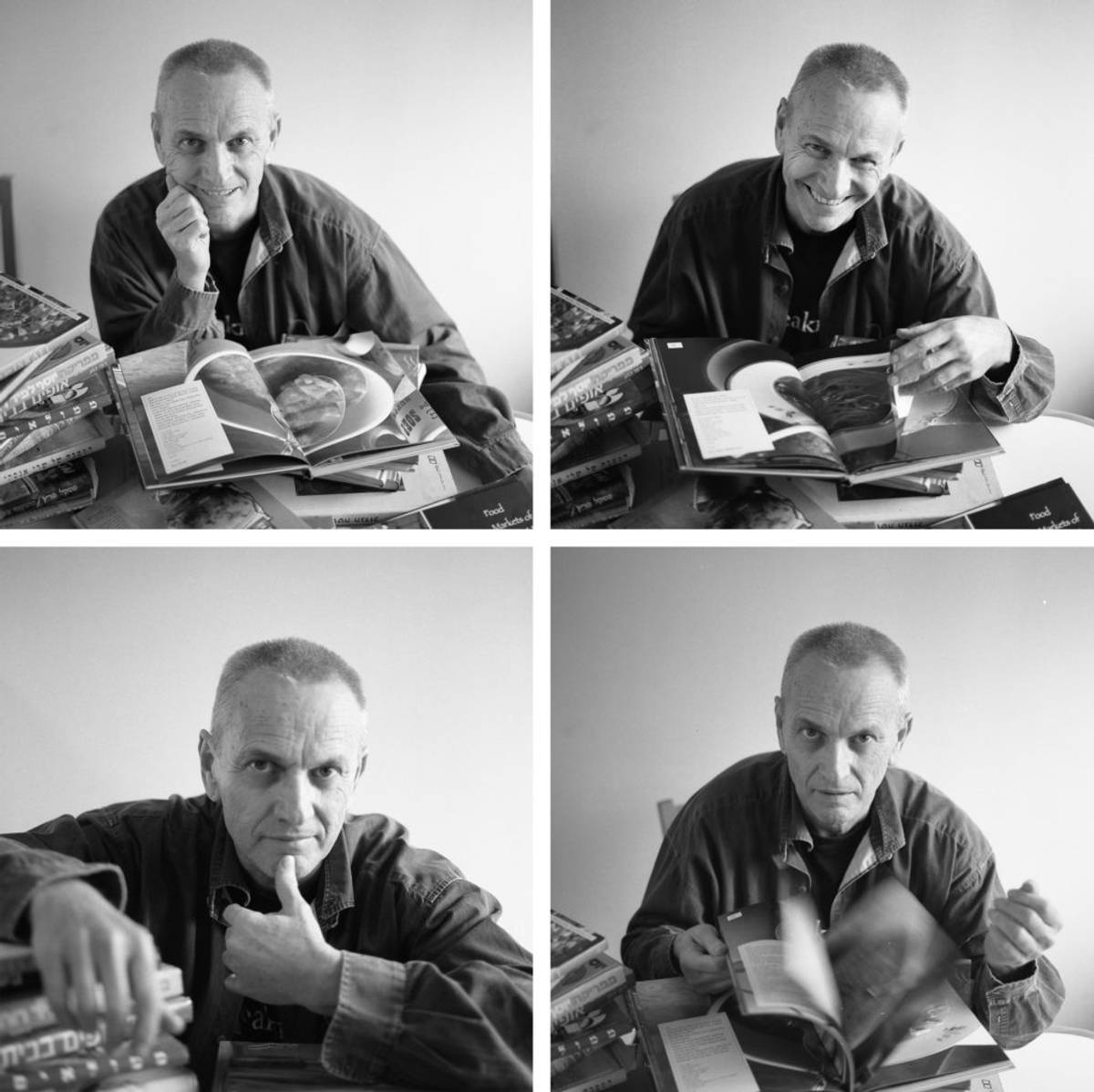

I obsessively consumed books and movies on this grim subject trying to get answers to impossible questions. I also began corresponding with Nelli, who gave me tidbits about the family I had never known. Most intriguing, he told me of the family elders that were still living, in particular, Nelli’s own mother, aunt, and uncle.

Very soon, it dawned on me that they might be able to help piece together what had happened to my grandmother’s closest relatives during the early years of World War II. Over the winter, I journeyed to Tel Aviv in search of answers—and I took my cameras with me.

***

The first of the elders that I met was Avigail, Nelli’s mother, who was turning 90 years of age. Avigail welcomed me at the door of her apartment with a warm smile. I was captivated by her piercing brown eyes and experienced an uncanny familiarity, as if I had known this person all of my life.

I noticed that among the stacks of reading material lining her apartment, were photography books authored by her son Nelli Sheffer. There were also rows of books on the topic of archaeology. I learned that in her prime, Avigail was a specialist in evaluating ancient Middle Eastern ceramics and textiles.

After several hours of getting acquainted and being joyously interrupted by a steady stream of neighbors, friends, and intermittent phone calls from other family members, we sat down to speak.

I had gathered some information beforehand: The family origins could be traced back to the town of Horodenka, in what is now southwestern Ukraine. For centuries, this territory, known as Galicia, was steeped in political controversy, and religious and cultural differences. Endless border disputes, particularly with Russia, inspired ethnic groups of the region: Ukranians, Poles, Romanians, Germans, and marauding Cossacks on a path of violence and racism. When the Bolsheviks seized power in Moscow, animosity was particularly focused on Jewish populations living in the small communities spotting the region. Jews, accused of sympathizing with Communists, were scapegoated, becoming victims of the relentless pogroms.

I asked Avigail my first question. Who was my great-grandfather (Avigail’s grandfather) Israel Menachem Wiesler? Did any photographs of him exist? Were there any photos of the children? Were there any photographs at all?

“There were none,” Avigail replied, and began instead to share what she knew.

At the turn of the 20th century, a young master carpenter, Israel Menachem Wiesler lived a life of relative subsistence in Horodenka. Their existence was meager at best, dire at worst. Jews, as second-class citizens, were not allowed to own land and were restricted to working in specific trades. In spite of this, Avigail explained, her grandfather’s reputation as a carpenter was well-known and widely respected.

Avigail remarked that Israel Menachem Wiesler, although still a young man, died tragically while his wife was pregnant with their sixth child. After the birth, Israel’s wife, frail and exhausted, was destitute without her husband. She died soon after. Avigail had no knowledge of how they died. To this day, their deaths remain a mystery.

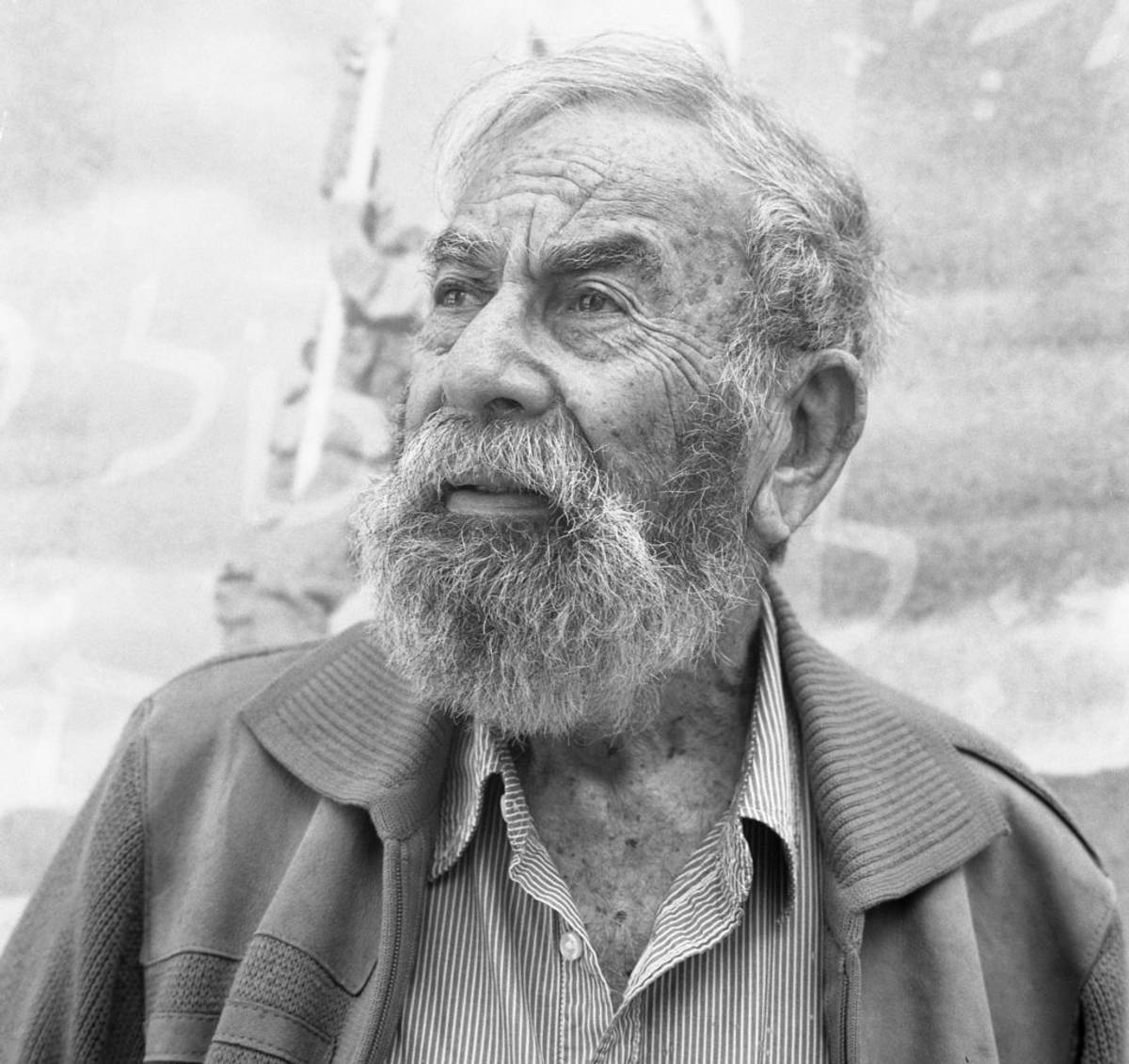

Left alone to fend for themselves and each other, the children looked to Emmanuel, their oldest brother, who they lovingly called “Manis,” to become the family’s new patriarch. Thankfully, Manis had learned well the skills of his father.

Avigail was clearly emotional as she looked down and fidgeted with her handkerchief. She continued: Not only did Manis absorb his father’s carpentry skills, she recounted, but he encouraged his younger brother Leibish, (Avigail’s father), to learn from him, so that one day in the future, he too, could be a family provider.

Avigail looked up, her big brown eyes filled with wisdom, directly locked with mine.

“Manis fell in love at a very young age and married a girl from the town of Sniatyn. His new wife convinced Manis to move from Horodenka, leave his brothers and sisters and resettle in her village.

“No one will ever know the grief that went into that decision,” Avigail remarked.

Manis’ three brothers and two sisters, with their lives at risk, fell into a desperate situation.

One by one, following their better instincts, the siblings left Horodenka, venturing into the unknown in an attempt to escape an uncertain fate.

“Your grandmother, by her own wits, found her way to America while still in her teens, while her other siblings followed Leibish, my father, and journeyed to Palestine.”

Once again we locked eyes. There was silence, and in that moment I realized something remarkable. Why did my grandmother make that fateful decision to separate from her siblings? By what means did she make it all the way to Bremen, the seaport to the north, and board a ship making the long voyage to America? Was she alone? Was she terrified? How did she get the money for passage ? I was deeply saddened as I asked myself why I had never asked her those questions while she was alive.

Avigail continued with her story: Recently married, Leibish and his bride, Adel departed in 1918 from Istanbul and boarded a ship headed toward Palestine. As the ancient seaport of Jaffa came into view, Leibish looked on as he saw men in small boats rowing out to meet the ship. For a small fee, the local Arab fishermen would bring the exhausted passengers to shore. Avigail told me that her father gave up his only pocket watch to secure their entry. Once on land, her parents were processed as new immigrants by the British authorities.

Leibish’s wife, Adel, emerged as a force of will and determination. She encouraged her husband to aspire to great heights and to follow in the footsteps of his older brother, Manis. Using his skills as a carpenter, Leibish worked around the clock to underbid his competition and economize in every which way. Little by little, individual carpentry jobs evolved into larger construction projects, as Tel Aviv began its expansion. Indeed, the business thrived, and in the meantime, Adel bore him three children: Aviva, Israel, and the oldest, Avigail.

By the time Avigail had finished primary school, it was the late 1930s. As tensions mounted in Europe and Hitler’s National Socialist Party was gaining in number and popularity, the family in Palestine beckoned Manis to join them. In this time period, the British severely restricted Jewish immigration to Palestine, but Leibish’s wits, intelligence, and professional status enabled him to secure work visas: legal documents to bring his closest brother, his wife, and children back into the fold and save them from being trapped in an inevitable war. It was a noteworthy act of devotion.

Leibish reasoned that he could not trust to send the documents by post. Visas were too precious and valuable. Instead, his wife would be “dispatched” to Sniatyn, inexplicably taking Avigail as part of the plan to persuade Manis and his family to leave.

Adel and Avigail would make the long journey by freighter across the Mediterranean to Istanbul, boarding a train north, and would arrive in Sniatyn after several days, where Adel would safely hand Manis the papers.

Upon their arrival in Sniatyn, it dawned on Adel that her efforts might not be successful. Emmanuel’s wife would not leave her elderly parents, who as it turned out, had no work or travel visas, and Manis would not leave without his wife and children.

Adel began her unrelenting efforts to persuade them otherwise. It was 1939. Did they not know about Hitler claiming the Sudentenland or annexing Austria? Did they not know about his sworn hatred of the Jews? Did they not hear about the Kristallnacht and the destruction of many synagogues in Germany? Did they not know that the winds of war were about to shift in their direction, and Poland would be next? Manis and his wife balked.

To them, it was unthinkable that their lives would be seriously imperiled. In the town of Sniatyn, they interacted with their non-Jewish neighbors. They attended the same celebrations, sporting and political events, and even shopped in the same marketplace! Besides, the Ukrainians, the Poles, and the Romanians all hated the Germans … so they believed.

I was in a spell as Avigail continued with her story.

“My mother was in a panic.” News of impending war did not stir the anxiety of the villagers, and her sister-in-law seemed intractable in her views, as Avigail recalled. Adel’s instincts guided her to a local priest to get a sense of the political and social temperature. Taking Avigail by the hand, they entered the church, which was “pin-drop quiet” and the air “filled with musk.” The priest looked up from his paperwork, as Adel took a seat and began asking questions. Cleaning his spectacles and looking uncomfortable, the priest beseeched her to “take your family and leave … now!” Avigail explained that the priest’s response was short and abrupt, hoping that his message could save them all.

It was getting late and maybe she was getting tired. Avigail was struggling to remember a painful part of her story, which involved the local train station.

I kept pushing her to remember what happened next.

Adel was hoping that Manis would be able to persuade his family to leave, especially after hearing what the priest had said. She instructed them “to wait for us at the railway station.” In the meantime, Adel hurriedly gathered enough food and clothing to sustain the family on the long trip. She brought Avigail to a local bath house where they carefully packed all these goods (including Avigail’s favorite blouse) into their single suitcase.

At the station, Avigail watched as the iron locomotive ground to a halt, its billowing smoke rings swirling through the crisp air of the September afternoon. As Avigail and her mother waited and waited, the anticipation was mounting. Reluctantly, Adel’s face turned white as she boarded the train holding Avigail’s hand. At the last moment, Manis appeared with the look of a defeated man. There was no family at his side.

Adel remained silent, her sad eyes following the suitcase as she passed it through the window into the large rugged hands of Manis. Avigail remembered that she pushed her head out the window as Manis, frozen in time, motionless, was left holding the suitcase. As the train departed, Avigail watched as Manis became smaller on the horizon until he disappeared into the distance. This memory, she said, was as vivid today as it was more than 75 years ago.

Adel and her daughter Avigail headed to Istanbul, boarding a freighter to Palestine. It was during their voyage home that they learned theirs was the last ship to depart before the Nazi blitzkrieg of Poland. They, too, could have been trapped. Instead, they headed to Palestine to build a new life and a new country.

Manis, his wife, his wife’s parents, and their children would disappear. History records that by 1942, the entire Jewish population of Sniatyn was brutally murdered in the nearby forest, or sent to their death in Belzec concentration camp.

***

I met many family members when we gathered together for a party a few days later. One by one, the family arrived at Avigail’s home. My Israeli cousins varied in shapes, sizes, ages, and points of view. I was struck by their colorful personalities and varied occupations, which included artists, music composers, military figures, retired university administrators, authors, teachers, and architects. Some were young mothers and fathers.

There was strength and joy in discovering my new family, although for them the circle felt complete. They were tightly knit, and family gatherings held a special importance.

“Distances,” my cousin Nelli remarked in a recent email, “are minor.” I hope so.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Barbara Mensch is a photographer living in Manhattan. Her work is in the collections of the Museum of the City of New York, The Brooklyn Museum of Art, Fundacion Televisa of Mexico City, the Biblioteque Nationale, and the Museum Of Fine Arts, Houston, among others.