Israel’s New Literary Currency

A pair of Hebrew-language poets get their likenesses on the shekel, but can they afford it?

“One day, I will grow up into a little-known, marginalized poet, writing in a half-formed language of uncertain future, but decades following my untimely death, my face will adorn the adopted motherland’s banknotes,” wrote, dreamily, no one ever. Then again, what does it even mean to be a “successful poet”? Earlier this year the Bank of Israel revealed that the portraits of two iconic Hebrew-language poets, Lea Goldberg and Rahel, will be gracing the state’s new banknotes. The announcement drew mixed reactions and spawned some interesting discussions about poetic legacy and how nations and their institutions get to determine that legacy. Some of the questions raised: Why these two poets rather than scores of others? Does being put on money qualify as adequate recognition of a poet’s contributions to language? Underlying all this, are, of course, the fundamental issues of politics, language, and the passing of time, and the way various forms of prejudice factor into these decisions.

One might recall Percy Shelley’s often-quoted line that poets are the “unacknowledged legislators of the world.” Indeed, poets may have something to do with ongoing metamorphoses of world’s mythology, ethics, philosophy, and thus, law—but would Shelley concede that poets are also the unacknowledged bankers of the world? People will buy potatoes and paper towels with these bills. They’ll torture one another and murder for them. They’ll pass them without a second thought. If this is how a poet is to be recognized, it is as counterfeit of a recognition as money can buy.

Then again, it is a commonplace that Israeli poets are revered by their readers—far more so than their American counterparts. For decades, the words of Lea Goldberg, Rahel, and numerous Hebrew poets have been adopted as lyrics for Israeli folk and pop music. To wit, Noa, Israel’s superstar and Eurovision representative, has set Rahel’s mournful poem “Barren One” to music. Can you imagine an American Top Hits radio station bouncing with covers of Emily Dickinson’s work? Walt Whitman in Justin Bieber’s mouth? It is inconceivable. In Israel, however, there’s a great deal of awareness of poets’ crucial contribution to the resurrection and formation of the modern Hebrew language. Elevated thoughts and meditations, elegance, melancholy, seduction—what hope for a national consciousness could there ever be with the purely utilitarian or political vocabulary in place? Perhaps, then, it is a gesture of recognition of the country’s real capital—imagination.

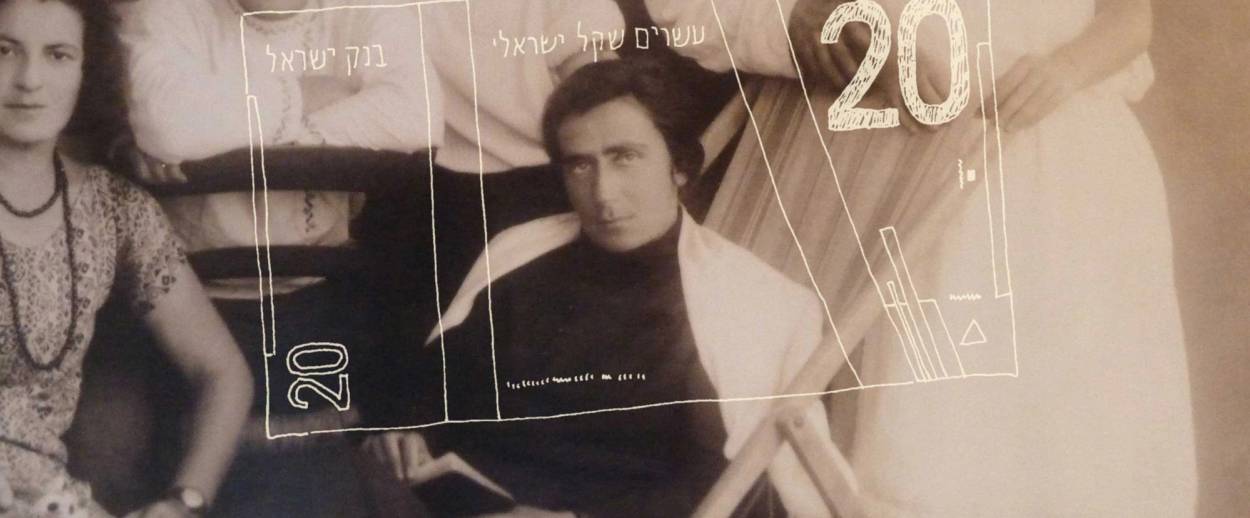

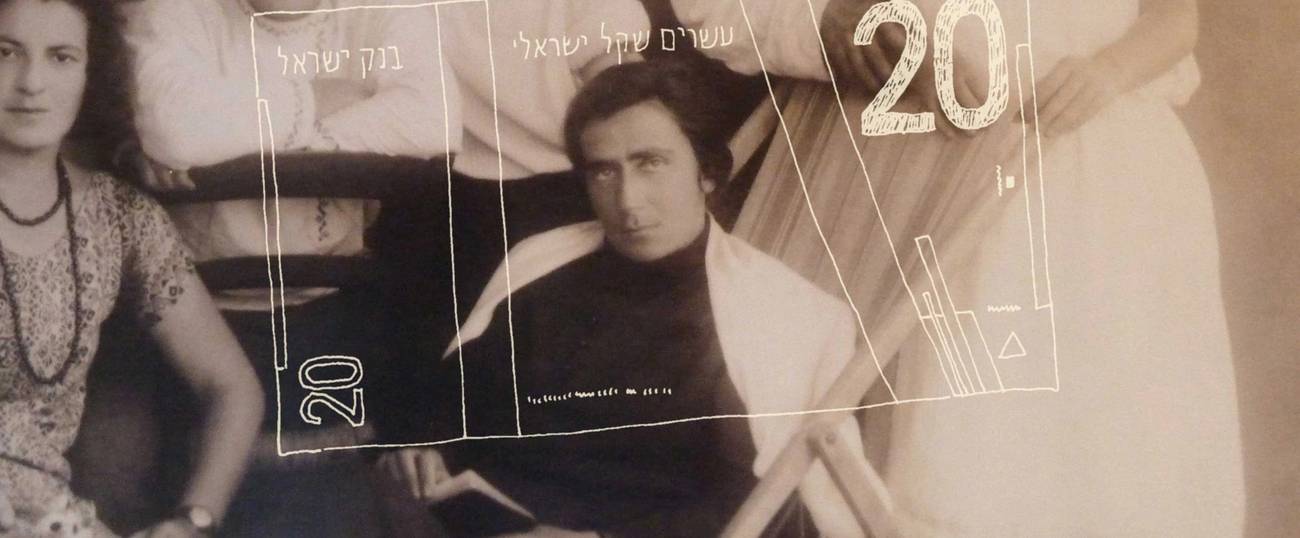

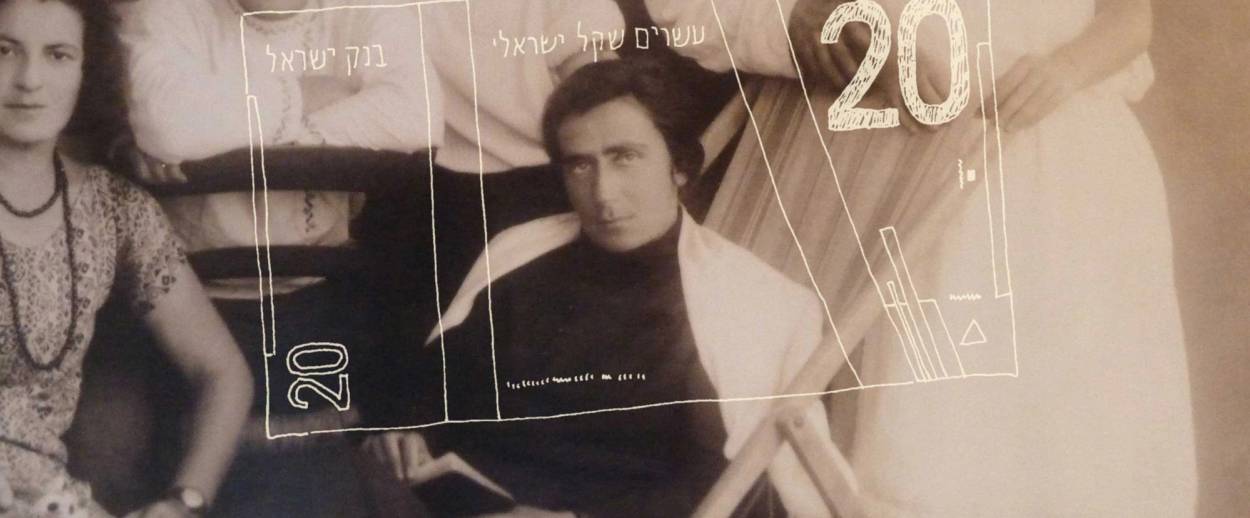

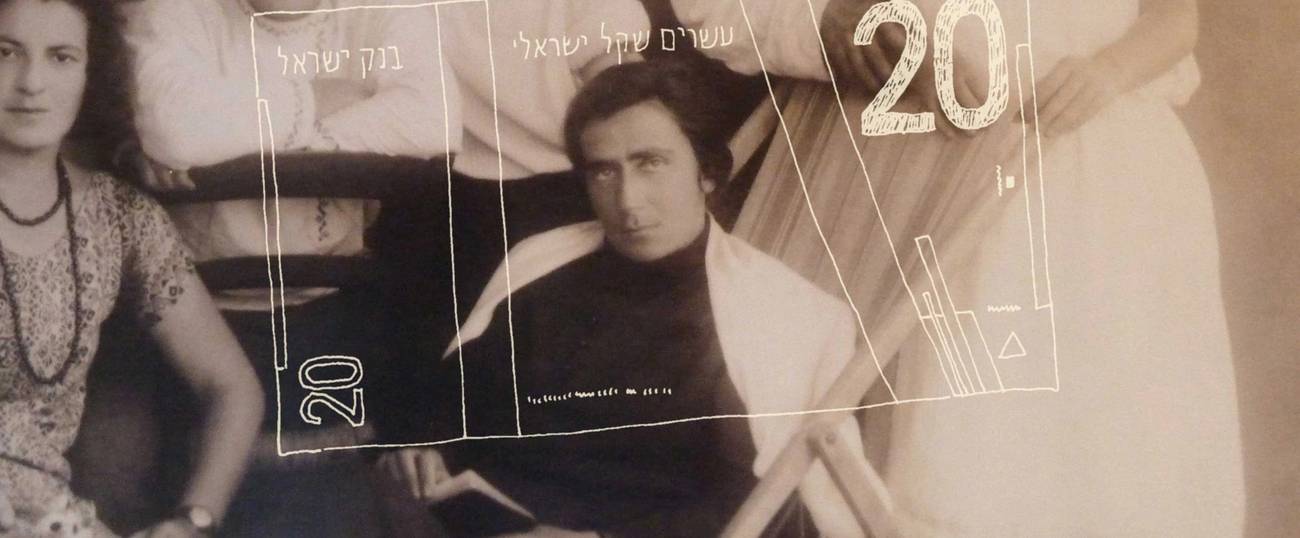

And yet, the gesture is fraught with pragmatic considerations that seem at odds with the very notion of poetry. Why is Rahel on a 20 NIS bill, while Lea Goldberg is on a 100 NIS? Is it because Lea Goldberg was far more prolific and renowned? Even if Goldberg produced about five times as many books as Rahel, would a purely quantitative calculation like this make any sense?

Significantly, the move was decried by some who contended that in recognizing only poets of Ashkenazi descent the bank was undermining and ignoring the contributions of Mizrahi poets. The bank previously selected Ashkenazi poets Saul Tchernikovsky and Nathan Alterman to appear on 50 and 200 NIS bills, respectively. The long-standing bias against those of Arab-Jewish or Sephardic descent is nothing new in Israel. Indeed, the awarding of the Israel Prize to Erez Bitton in 2015 marked the first time that the prestigious prize was given to a Mizrahi writer. This time the situation turned truly farcical when Sari Raz, a member of the selection committee, told the press that, in all earnestness, she wasn’t aware of any worthwhile 20th-century non-Ashkenazi poets. She pointed to the medieval Spanish-Hebrew poet Yehudah Halevi as a worthy contender, except for the lack of a photograph.

In the meantime, literature written by Mizrahi writers has been thriving for years. The latest group, led by the young poet Adi Keissar, has drawn a great deal of public—if not the establishment’s—attention, which only goes to show that poetry’s greatest currency, its immediacy and impact, continues to thrive on the margins. It is on the margins, too, that poetic currency makes its bid for infinity—for that mysterious chance that a tangle of words will remain relevant and contemporary long after its composition.

***

There is no doubt that both poets, particularly Rahel, were indeed marginal characters in their time. Born into a wealthy Russian Jewish family, Rahel Bluwstein Sela, later known as Rahel the Poetess, or simply Rahel, came to Palestine as a tourist and fell in love with the land, as well as its inhabitants. A student of visual arts and literature, Rahel vowed to prioritize manual labor and “paint with the soil, play with the hoe.” In some of her most original, and moving poems, physical labor and poetry merge, nourishing one another. Thus, in “Our Garden,” dedicated to her mentor, early Zionist agronomist and feminist, Chana Meisel, Rahel writes:

Spring and early morning—

do you remember that spring, that day?—

our garden at the foot of Mount Carmel,

facing the blue of the bay?

You are standing under an olive

and I, like a bird on a spray,

am perched in the silvery tree-top.

We are cutting black branches away.

From below your saw’s rhythmic buzzing

reaches me in my tree,

and I rain down from above you

fragments of poetry.

Remember that morning, that gladness?

They were—and disappeared,

like the short spring of our country,

the short spring of our years.

It is clear that this “garden” has an Edenic resonance, and the images of the actual work—the saw’s buzz, the pruning—function metaphorically, as well. The silvery tree-top, perhaps an allusion to a flowering tree, becomes both the source of inspiration and the stage, while the “black branches,” which are being cut are reminiscent of all that is ready to be cast away—personal and communal past, history’s regretful turns, one’s never-ending doubts.

The ominous sadness permeating the poem alludes to the poet’s fate. On a visit to Russia, where she was volunteering at an orphanage, Rahel contracted tuberculosis—the cause of her untimely death at the age of 41. In a poem “To My Country,” she addresses the land she fell in love with:

Modest are the gifts I bring you.

I know this, mother.

Modest, I know, the offerings

of your daughter:

Only an outburst of a song

on a day when the light flares up,

only a silent tear

for your poverty.

Robert Friend’s translation does not quite capture the nuanced shifts between the biblical language and the vernacular Rahel was adopting. The word offering, in the original, connotes a sacrifice, or a prayer—minchah. Similarly, the “outburst of a song”—in the original, truah, shofar’s cry—seems to imply a primordial, prayerful pushing up against the wall of language. Friend’s translation, somewhat dated by now, of a small selection of poems is the only one available to English-speaking audiences at the moment.

In 2015, scholar Nurith Gertz published a book exploring one of Rahel’s key romantic entanglements. An Ocean Between Us has appeared on Israel’s best-seller lists, and has not yet been translated. To Tablet’s email query about commemoration of the poet, Gertz wrote: “A NIS 20 banknote has nothing to do with cultural memory. Rahel can be found in the places she lived in: the Sea of Galilee, the Degania kibbutz, and as part of our cultural memory. But there is no one banknote that can convey who Rahel was, or, for example, the meaning that the Sea of Galilee held for her. She is part of a cultural memory that is slowly fading, together with the first Aliyah movements and the early settlers. Banknotes, however, will not revive this memory.”

The scholar Giddon Ticotsky, an editor of Lea Goldberg’s work, however, is more optimistic. In an email, he noted: “I know that many people criticize this move as they consider mixing of arts and money improper, but I really like it. I think that the fact that every Israeli will soon have in his wallet or her purse something evoking poetry, and these dear figures, is simply fantastic. Think of the kids seeing these banknotes and asking their parents who was Lea Goldberg or Rahel (in case they haven’t known them earlier), and their parents explaining (and even exploring a little bit) … it’s really heartwarming. Also, I consider it a beautiful statement made by the State of Israel, that poets—not generals, politicians, etc.—are those who should be cultural heroes.”

Ticotsky’s perspective is extraordinarily poetic: He seems to imply that, in a hopeful reversal of our current world order, the banknotes will become a form of advertising of poetry, and the poetic capital. Perhaps the poets will draw more customers this way! Indeed, whatever the motivation of the decision-makers, poetry’s stock has suddenly soared—and the discussions around the dedication may elicit useful questions that otherwise would not have been addressed.

***

In addition to being a poet, Lea Goldberg was a renowned translator from various languages (including Russian, German, and English among others), an academic scholar and lecturer, a playwright, and a children’s book author. Her work has been available to English-speaking audiences through the efforts of a terrific American-born Israeli poet, Rachel Tzvia Back. In addition to the Selected Poetry and Drama collection from a decade ago, Back has recently translated a selection of Goldberg’s later poems—Goldberg’s most complex, experimental material. The new collection will be published this May. In the memorable opening piece, the poet observes:

A young poet suddenly falls silent

in fear of telling the truth.

An old poet falls silent fearing

the best in a poem

is its lie.

As Back explains in her illuminating introduction to the book, the poem references Moses Ibn Ezra, Medieval Jewish poet, who noted that the “the best in a poem is its lie.” The poem is far from skeptical—it is about the gradual movement of a poetic consciousness. Early poetic experiments with self-discovery culminate in a stunned, ominous silence; an experienced poet arrives at the recognition of the poetic artifice—the so-called lie, the imagination—as the ultimate source of self-understanding.

In terse, abrupt fragments, some of Goldberg’s lines—slanted, mysterious, self-referential—are reminiscent of those of Emily Dickinson. In one fragment, she writes:

The face of the waters

and the lesser light

and the spoken word was with God—

And why do we stand

before this strange house

with its blinds drawn?

The poem clearly echoes the biblical account of creation—the divine utterances, the moon, the primordial flow. Here, however, the images are loosely joined, and somewhat altered—the “spoken word” appears to be held back, restrained, or silenced by the creator. The epic images of the first stanza clash with those of the second—in particular, the “blinds.” There isn’t a narrative or a story here, but the mere shreds culminating with the question. What sort of a house is Goldberg describing here—language in general, or Hebrew in particular? Is this poem about creation of the world, or the poetic creation? Is the creator God or a human being?

The poem that best addresses the question underlying this article, however, is the one below:

Answer

To the exam question “For what purpose

are lyric poems written in our era?”

And what would we do with the horses in the 20th century?

And with the does?

And with the large stones

in the Jerusalem hills?

The well-known tendency to answer the question with a barrage of questions is reversed in this poem. The three final questions are more than a pose, or a comeback, or even a philosophical stance. These questions, indeed, address the examiner’s query. Poetry’s value, and its place, argues the poet, is inseparable from the world that engendered this poetry. Inasmuch as one can’t put a price on the stones of Jerusalem, on the myths and dreams associated with the ancient, biblical city, inasmuch as one can’t affix a price tag to the whole species of horses—so, too, poetry cannot be assigned a value. If anything, judging prevalent attitudes toward poetry within a given society, one can begin to surmise the society’s attitude to the self, and the world around.

There’s no doubt that both Rahel and Lea Goldberg deserve the dubious honor that has been thrust upon them, and the new wave of attention that will, hopefully, accompany it. Perhaps, in some ironic Ponzi-scheme moment, more of the new 20 and 100 NIS bills will be used for purchases of poetry books, and not only those written by poets of the past, but also the books of those still present—the living poets, who carry just as many questions, and just as many holes in their pockets.

***

Read more of Jake Marmer’s Tablet magazine essays on poetry during April, National Poetry Month, here.

Jake Marmer is Tablet’s poetry critic. He is the author of Cosmic Diaspora (2020), The Neighbor Out of Sound (2018) and Jazz Talmud (2012). He has also released two jazz-klezmer-poetry records: Purple Tentacles of Thought and Desire (2020, with Cosmic Diaspora Trio), and Hermeneutic Stomp (2013).