The country of Norway didn’t formally come into existence until 1905. But one has to go back a long way before that to get a full sense of the country and its history. What we now know as Norway was a Viking and a Norse power until the Black Death weakened it, and forced it into an unwelcome union with the Danish crown. If you look at the map and compare the two countries, you’ll see at once how dwarfed Denmark is by Norway. A good-sized population may be locked within the Danish landmass, but in geographic terms, the country is tiny. It was true that Norway continued to have its own institutions and laws, but power ultimately lay with the king of Denmark in Copenhagen. That state of affairs continued until 1814, when Denmark came out on the losing side in the Napoleonic wars and ceded Norway to Sweden. That momentous year marked the effective birth of the country of Norway, and what follows concerns that crucial year and those that followed.

In 1814, the Norwegian Constitution was put together, piece by piece, not far from what we know today as Oslo. The men who devised the constitution were inspired by the values of the French Revolution and by all that lay behind America’s Declaration of Independence. In Europe, there was little that compared with this new and brave document from Norway; it was remarkably forward-thinking and wise. Except with regard to one clause that at once rendered it racist, and distinctly out of step with more enlightened thinking in other European countries. No Jews were to be permitted to come and settle in the new and independent state of Norway.

In actual fact, the paragraph that banned Jews from Norway simply extended the powers of a law from 1687—when the then king had declared that no Jews could come to live in the country without royal approval. But those final three words were important: royal approval might be hard to win, but at least a flicker of hope existed that it could be a reality. Now even that hope was taken away.

There’s been plenty of debate over the years about where this anti-Semitic decree came from. For a long time, it was believed it simply reflected what was sadly to be found in the Norwegian people as a whole—namely, a deep-seated prejudice that was based almost entirely on ignorance, because the truth was that few if any Norwegians had encountered Jews. More recent thinking has centered on the group of men who worked on the creation of Norway’s revolutionary constitution. It’s now reckoned that their personal views had much to do with the crucial clause that banned Jews from coming to settle. Yet even here, things have to be nuanced: It’s far from the case that an overwhelming majority of these otherwise enlightened men were hell-bent on keeping and even strengthening a law that had been in their country for over 100 years. There was real division within the group, and without doubt it caused both debate and frustration. At the end of the day, the clause was adopted, but there were some who certainly saw it as decidedly illiberal and against the spirit of all they were seeking to create—not only for themselves but for generations to come.

One of the men behind the constitution was a preacher by the name of Wergeland. He had been appointed priest in the very community where the constitution was decided on and ratified in 1814. That meant his young family had the most extraordinary start in life. The volcanic lava of the new Norway was hot around their very feet: The principal characters in the story of Norway’s foundation would be in their father’s study and out in the yard beyond its windows. But it wasn’t just the important figures whose voices they would have heard on a daily basis, it was also those of the ordinary farming community. That became particularly important for the young Henrik Wergeland, a son of the vicarage 9 years old when the family moved there.

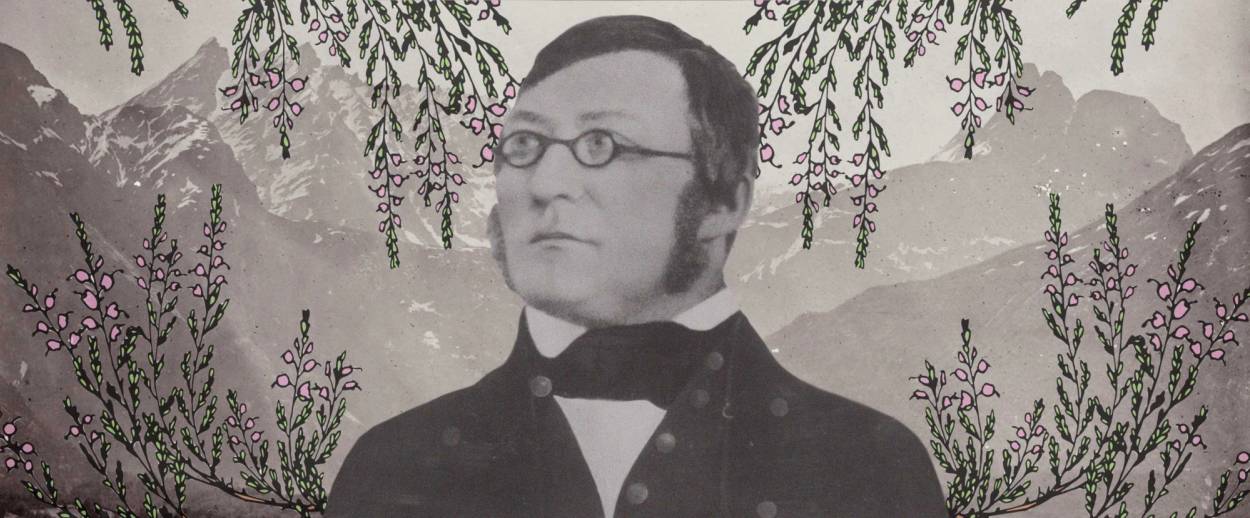

Henrik went on to study theology like his father, but he was destined to become a writer rather than a theologian. Nonetheless, that religious foundation was fundamentally important for his thinking in later life. And during the few decades that he lived, he did a great deal in the way of thinking; he became, in the end, a radical. And like all those who dare to think so controversially he won plenty of enemies: He was unafraid of making his views known, particularly in the plays and poetry that poured from his pen.

And one of the things that came to haunt him most was the clause banning the Jews from settling in Norway. It may be that a meeting in Paris with two Moroccan Jews in 1831 had a crucial impact on him. What’s certainly true is that he must have had many a bitter debate on the subject with his father: the latter was one of the signatories to the constitution who for long enough believed wholeheartedly in the rightness of the presence of that clause. Like many others in Norway, he saw this with the religious eyes of the day: Banning Jews from Norway was nothing less than a Christian necessity. His son believed the opposite: How could a so-called Christian society behave in such an unloving and discriminatory manner? Had Jews not been created also by the hand of a loving God? How could it be that we cast them from our midst and condemned them to vilification?

Of all the many works that Wergeland created, his poem “Christmas Eve” is perhaps the most important—and for good reason. Because he devoted the last 15 years of his short life to battering at this oaken door: He was determined the clause should be repealed.

It has to be remembered that Wergeland was a romantic poet writing at a time when such writing was the order of the day; as a result, our eyes simply struggle to read his work easily today. All the more important, then, to see it within the context of his time, and to get some sense of the impact it had in that time.

Who cannot call to mind a storm, a tempest

so fierce he thinks that Heaven no worse can send?

So begins Wergeland’s epic poem.

In “Christmas Eve” a Jew by the name of Old Jacob is wandering from place to place selling a variety of things in order to do little more than survive. It’s Christmas Eve and the weather deteriorates to such an extent that a full blizzard is raging about the old man.

In such a storm—it was the eve of Christmas—

when the tall night o’erstrode the cowering day—

thro’ Sweden’s wilderness, the Tived forest,

an old Jew heavily was plodding onward

It was by no means accidental that he is crossing from Sweden into Norway, for Sweden’s borders were far more open to such a traveler. But once on the other side, in Norway, he hammers at the door of a house, and those inside wave him away, tell him in no uncertain terms that he will not find shelter from them.

‘Jew!’ thereat cried terror-stricken

together a man’s and a woman’s voice.

‘Then keep outside! We have nothing to pay with.

Misfortune shouldst thou bring into our house,

this night when He was born thou slewest!’

When Old Jacob goes back out into the storm he finds a young child, a little girl. She is one of the daughters of the family that has just sent him on his way. But the poem states that the old man is more affected by the cold and the hard-heartedness they have shown him than by the bitter chill of the wind and the snowflakes. He hugs the young girl close to him as the storm worsens and the dark envelops them, but in the morning the family finds both frozen to death.

This is their response when they go out into the new day:

‘Oh, God has punished us! The storm has not, but our own cruelty has killed our child!’

When the Norwegian people read this poem the message was hardly difficult to discern. It was they who had banished Old Jacob from their homes—perhaps not literally, but figuratively speaking. It was they who had refused him shelter. Wergeland pulls no punches—it has been because of the so-called Christian views of the family on whose door the old man hammers that they do not let him in.

Highly romantic though it was, and designed to make Christmas eyes weep, Wergeland’s purpose was clear, which was to awaken his people to the reality of the asp in the heart of their newfound and hard-won constitution. They had to see that the clause went against the whole spirit of the constitution, and the very character of the Norwegian people.

Henrik Wergeland did not live to see the day when the Oslo parliament finally decided that the ban would be repealed. He died while still a young man, writing as fast as the paper and the pen would carry his words. He was not always a man loved by his own people; they were all too aware of his rather wild living and unconventional thinking, and a young and politically conservative country like Norway was not ready to endorse his eccentricities. Yet when he did die, they came in droves to his home; they came to honor his goodness and courage, the bravery that was bigger than all his mistakes.

One of the most important things he did was to campaign for a Norwegian national day—the 17th of May. That was the day the constitution had been signed when he was just a 9-year-old boy, barely yards from the house where he grew up with his siblings.

How ironic that when Menachem Begin collected his Nobel Prize for Peace in December of 1978, the ceremony took place not, as it had until that time, at Oslo University, but rather at Akershus Castle—where Henrik Wergeland wrote with such passion about the so-called Jewish clause he so yearned to see deleted from the constitution. And to this day, the Jewish community in Norway honor Henrik Wergeland by laying roses at his grave each May 17. They do so to pay homage to his determination to see the Jewish people accepted as citizens of his country, to see an end to the racism and the sheer ridiculousness of a clause that kept them shut out for so long, and whose echoes continue to reverberate in the public statements and thoughts of some of Norway’s leading politicians. Yet there is no doubt that a simple poem made a difference.

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.