Yiddish Mumblecore

Rokhl’s Golden City: The ethnographic impulse in Joshua Z. Weinstein’s ‘must-see’ film, Menashe

Don’t call it a [Yiddish cinema] comeback/it’s been here for years. Director Joshua Z. Weinstein’s brilliant new Yiddish mumblecore heartbreaker Menashe opens this week, and it is an absolute must-see. And not because, as some will inevitably claim, it’s some kind of first. Actually, you should be suspicious when you see publicity claims of a first Yiddish this or that. Who cares if it’s a first? (It almost never is.) The more urgent question is, as always, is it any good? (Spoiler: Menashe is good. Very, very good.)

In the postwar period, there have been a number of North American feature films either in Yiddish or with significant Yiddish content: Hester Street (1975), A Gesheft (2005), Romeo and Juliet in Yiddish (2010), The Pin (2013). Probably the closest comparison with Menashe is the ultimately disappointing Felix and Meira (2014), also a story about a young person suffocating in the confines of a closed Hasidic community.

Being good is a lot harder than being first. And when it comes to Yiddish, there are so many tricky details to get right before you can get to the finish line of a successful artistic product, however defined. Who’s going to write your idiomatic Yiddish dialogue? And who’s going to perform it? And if the accuracy of your dialogue and its performance don’t matter, why even bother? But Weinstein, aided by a team of Hasidic Yiddish natives, OTD (off the derekh) translators, and non-Hasidic Yiddishists, pulls it off, astonishingly so.

Menashe tells a story inspired in many ways by the real-life trials of its star, Menashe Lustig. In the film, Menashe’s community leaders have ruled his home unfit for his son until the widowed Menashe remarries. But perhaps Menashe doesn’t want to remarry? And who is to say if his home is fit or not? Menashe is a rebel against the ritualized stringencies of the Hasidic world. But his rebellion is quiet and slow-simmering; he’s the rebel who won’t leave. He doesn’t want a revolution, he just wants the right to make his own mistakes without having to give up his family or community. This makes Menashe, and the sacrifices he must contemplate, deeply complicated and eminently relatable. The beautifully executed specificity of the language, as well as that of the entire mise en scene, only adds to the ultimate universality of the story.

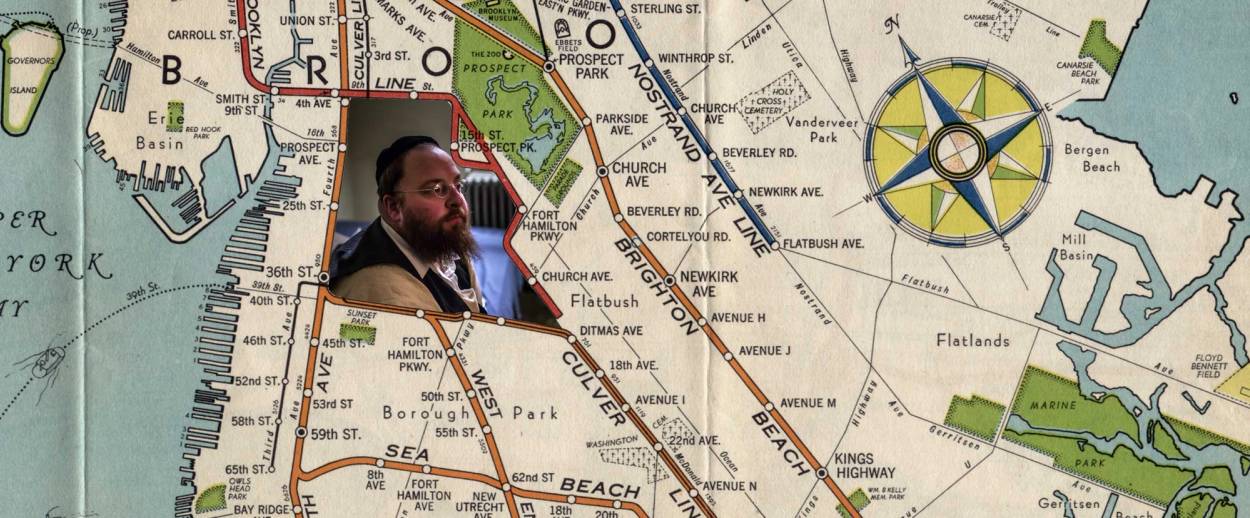

Weinstein himself says, “I decided to look at Borough Park from an ethnographic, sociological lens.” It’s that ethnographer’s eye which is key here. In her essay Objects of Ethnography, Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett writes that “those who construct the display constitute the subject. … They are thus exhibits of those who made them, no matter the ostensible subject.”

Weinstein isn’t just an American Jew, the grandson of a Brooklyn toy store owner, the one-time little boy fascinated by the “exotic” neighborhoods of Borough Park and Crown Heights. He’s also a film-school graduate, director, cinematographer, and recipient of NEA grants. He is a sophisticated artist and clearly aware that he is a non-Yiddish-speaking outsider with responsibilities that flow therefrom. His outsiderness, paradoxically, is what brings the audience that much closer to an otherwise-inaccessible world.

From one closed-off world to another. The Congress for Jewish Culture, in cooperation with YIVO, will be presenting a new Yiddish-language documentary this week, Chaim Beider: Poet, Editor, Essayist. The named subject is a quiet hero of the postwar Soviet (and beyond) Yiddish literary world. After the fall of the Soviet Union, Beider immigrated to New York City, where he worked with Boris Sandler, the director of the documentary, at the Forverts.

Over many years, Beider compiled the Biographical Dictionary of Soviet Yiddish Writers, a massive undertaking that was finally published by the Congress for Jewish Culture in 2011. The Biographical Dictionary was a landmark achievement, correcting and supplementing information that hadn’t been updated since the beginning of the Cold War. Beider knew many of the authors he profiled personally, and sadly died before its publication. However, the film and the Biographical Dictionary are both causes for celebration. The wheels of Yiddish culture and scholarship sometimes move slowly, but they move.

And speaking of celebration … who goes to a nightclub on a Monday night? As it turns out, I do. And Shane Baker. And a roomful of well-heeled international tourists. (Incidentally, did you know how much it costs to go to a nightclub? They never mention that in all the old movies where people seemed to spend most of their times being elegant and grown-up.)

Shane and I were at the swellegant Feinstein’s/54 Underground last week to see Eleanor Reissa bring the house down with some very sexy reimagined Yiddish classics. She was backed by Frank London and a scorching-hot band, sort of the klezmer equivalent of being backed by the Dap-Kings.

As a happy bonus, seated at our table was Michael Posnick, son-in-law of Usher Penn, author of the written-in-Yiddish, set-in-Cuba epic poem Hatuey: Memory of Fire. Over the last seven years, Hatuey was transformed by Frank into an opera and, miraculously, brought full circle to Cuba in March. It was Posnick who made the Cuba premiere possible, he and his wife having been key supporters of the project from the very beginning. It was a double pleasure to be out on the town as well as have the chance to celebrate the first (dare I say?) Yiddish-Taino jazz opera. Every Monday night should be so special.

***

Give: While the fictional Menashe finds a way to be himself and stay within the ultra-Orthodox community, many are unable or unwilling to stay. Footsteps is a wonderful outreach organization that supports those who have left. YAFFED is an advocacy group focused on improving educational standards within Hasidic schools.

Watch: Chaim Beider: Poet, Editor Essayist, (in Yiddish with English subtitles). Thursday, July 27, 6:30 p.m. at the Center for Jewish History. Free, though reservations are recommended.

More Yiddish Documentaries: I cannot overstate how good the League for Yiddish’s Worlds Within a World: Conversations With Yiddish Writers series is. I know, talking-head interviews aren’t necessarily the sexiest kind of documentary. But the combination of fascinating subjects (all subtitled in English) and skillful direction by Joshua Waletzky make these must-haves for students and Yiddish literature lovers.

ALSO: Even if you can’t be a student in the YIVO summer program you can take advantage of their superb summer events. Wednesday, Aug. 2 is the Summer Yiddish Song celebration featuring some of my favorite artists, like singer-songwriter Miryem-Khaye Seigel and Eleonore Biezunski. Way back in the day, when I ran supertitles for the Folksbiene, I had the pleasure of working on a show with the multitalented Steve Sterner. Aside from acting in the Yiddish theater, he is an in-demand silent-film accompanist. This Sunday, July 30, he’ll be at Film Forum providing music for Lois Weber’s THE BLOT. And while you’re at Film Forum: Snake Plissken is Jewish, right? I can’t be the only one who thinks that. In any case, there can’t be a more appropriate time to catch Escape from New York (Film Forum, July 28-Aug. 3) than during this officially designated summer of transit hell.

Rokhl Kafrissen is a New York-based cultural critic and playwright.