No Yortsayts, Please. We’re Yiddish.

Rokhl’s Golden City: Why reports of the death of Yiddish theater are greatly exaggerated

Fremde geter dint men, un yidishe yortsaytn pravet men. (We worship foreign gods and commemorate Jewish deaths.) Avrom Golomb, the still unheralded philosopher of the diaspora, wrote these words in the magazine Afn Shvel in 1945, a year that saw both the catastrophic end of the war as well as the celebration of the 30th yortsayt of I.L. Peretz. Yiddish writers in America were reckoning with a new communal configuration in which North America was suddenly at the center of global Yiddish life.

In her essay “Harbe Sugyes/Puzzling Questions: Yiddish and English Culture in America During the Holocaust,” scholar Anita Norich describes how writers like Golomb feared Yiddish would become a place of consolation rather than creation, a yortsayt kultur (in Golomb’s words) focused on death, not life. As Norich notes, Yiddish writers “were expected to lament the destruction and console the Jews” while “American writers were not expected to end their ongoing cultural life because of the times.” “Oys mit Peretz-yortsaytn” (an end to Peretz anniversaries) was the defiant title of Golomb’s 1945 essay. Of course, Golomb didn’t want to end Peretz anniversaries or any kind of yortsayt. Golomb sought to integrate the great need for commemoration with a drive forward to create anew. But how? It’s a thought I come back to often in my own work of 2018. As Chazal say, He who isn’t busy being born/is busy dying…

The Congress for Jewish Culture sponsors some of the most important yortsayt events on the Yiddish calendar. On Jan. 18, the Congress is presenting the 70th yortsayt tribute to Shloyme Mikhoels, the legendary director of GOSET [Moscow State Yiddish Theater] from 1929-1948. Mikhoels was an unparalleled figure of Jewish cultural and political activity, something for which he paid, like many others, with his life.

The first lady of the New York Yiddish stage, Yelena Shmulenson, will be taking part in the event. I asked Shmulenson what meaning Mikhoels has for us today. Shmulenson, who grew up in the FSU, emphasized how important Mikhoels was for Jews who had few permissible “Jewish” places in Stalin’s USSR. But more than that, Mikhoels and GOSET “showed the whole theatrical world what could be done in Yiddish. If we don’t talk about things like Mikhoels and GOSET, then everything will be forgotten, and we will be stuck with nothing but cloying musicals in Yiddish forever.” Indeed.

In a way, Mikhoels embodies the mesorah of high modern Yiddish theater. Mikhoels’ theatrical career started when he was recruited by Aleksandr Granovskii for his Jewish Chamber Theater, the forerunner of GOSET. Granovskii, a non-Yiddish speaker, began his artistic journey when he traveled to Germany where he was trained by another non-Yiddish speaking Jew, Austrian Max Reinhardt, “the man who invented modern theater direction.”

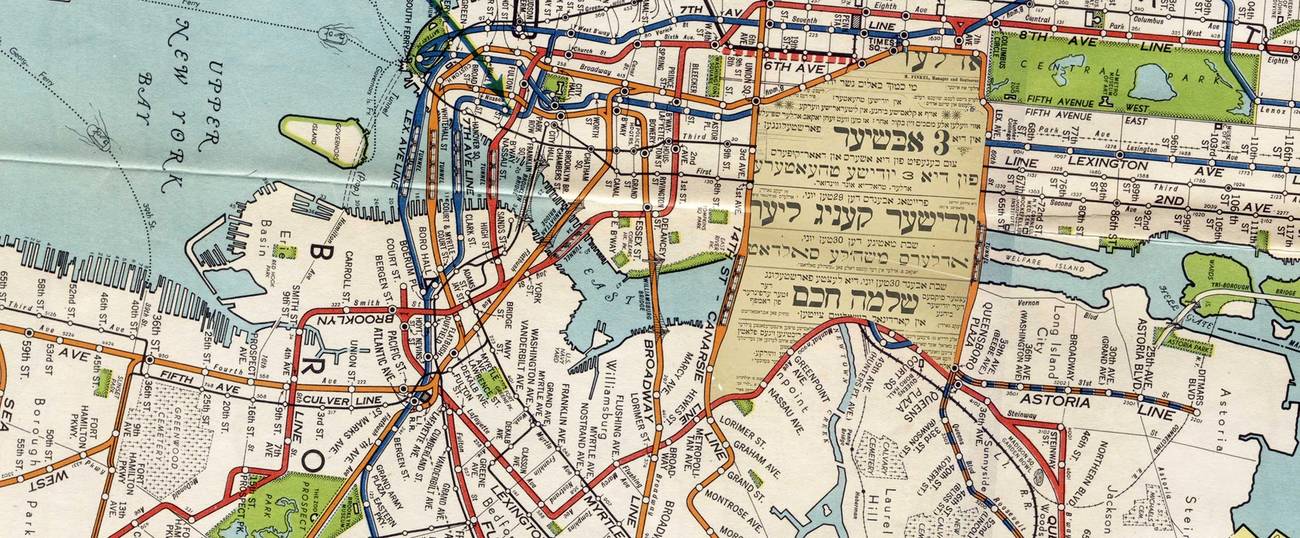

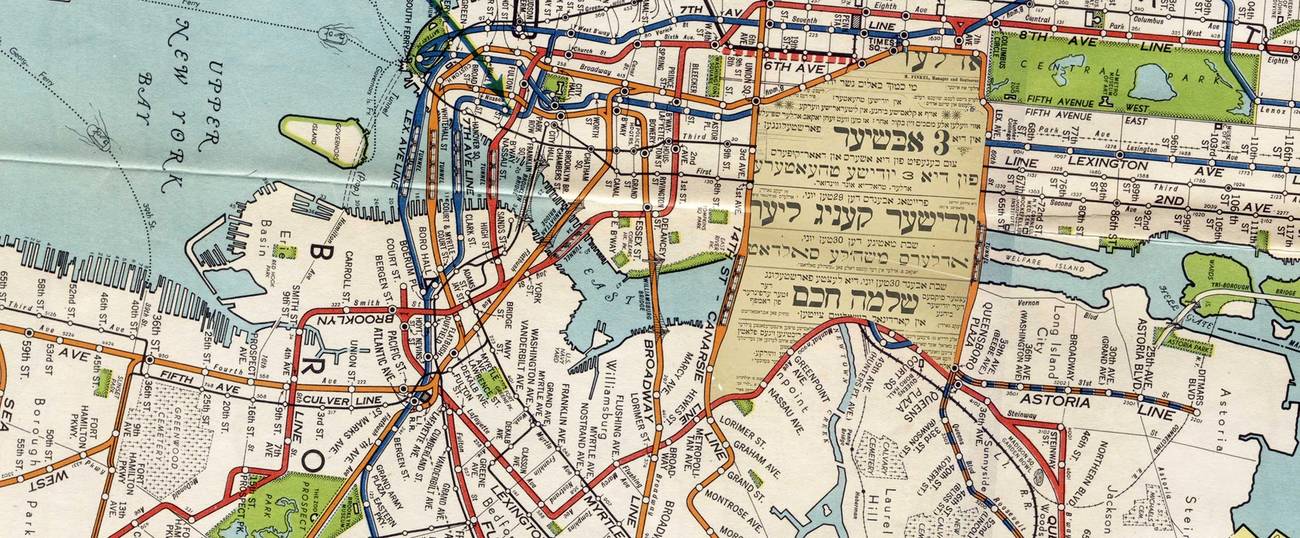

Yiddish theater has always been in tension with the larger artistic world around it. There was no native Jewish tradition of theater aside from things like Purim shpils. It’s no surprise to learn that, for example, GOSET was founded by a non-Yiddish-speaking theater artist. And as Yiddish theater paradoxically flourishes in a largely non-Yiddish-speaking world, that tension between cultures continues to bear fruit. I just got a communiqué from Theater J in Washington, D.C., Their new(-ish) director, Adam Immerwahr has launched something called Yiddish Theater Lab. Over the year the Lab will “uncover and reinterpret nearly forgotten Yiddish classics in new English language readings, workshops, commissions, and eventually productions.” The lineup looks really great, with two from Jacob Gordin, The Jewish King Lear (Jan. 8) and God, Man, and Devil (April 18) as well as one of my favorites, Ossip Dymov’s surreal New York subway fantasia, Bronx Express (June 18).

I’d quibble with Theater J’s characterization of these works as “nearly forgotten.” These are not obscure texts. Something like God, Man, and Devil is only “nearly forgotten” in the sense that American Jews have excelled in nearly forgetting nearly everything if it came from earlier than, say, last week. Still, a vibrant Yiddish theater scene in America will necessarily include English translations and reinterpretations alongside Yiddish language productions. And the opposite, too. Harking back to the tradition of Second Avenue’s “farshenert un farbesert” Yiddish translations of Shakespeare, I was thrilled to see the Folksbiene announce they’ll be mounting Shraga Friedman’s brilliant Yiddish translation of Fiddler on the Roof. I have a lot more to say about the significance of Fidler oyfn dakh, but perhaps that will wait until we’re closer to opening.

Nokh a yortsayt (yet another memorial) … I hope some of you got to participate in this year’s Yiddish New York festival. Every moment was its own sort of miraculous mini-highlight, but the true highest highlight for me was the Sixth Annual Adrienne Cooper Legacy Concert and Award Ceremony. In addition to a phenomenal musical program (this year, a reimagining of Every Mother’s Son, the antiwar song cycle she co-created with pianist Marilyn Lerner), each year an artist is chosen for the Dreaming in Yiddish award. It comes with a hefty (for the Yiddish world) check, acknowledging a unique contribution to the world of Yiddish art, activism, and education.

Michael Wex, a previous Dreaming in Yiddish recipient, opened the evening with a tribute to Adrienne, drawing on their many years of friendship and collaboration. I found Wex’s speech so moving I asked him if I could excerpt a bit of it for you. Here he’s speaking about Adrienne’s signature song, Peace in the Streets/Volt Ikh Gehat Koyekh, a Hasidic song she transformed into a song of peace and radical inclusion, not to spite contemporary Hasidic life, but as a rebuke to those who speak of peace but bring none:

that’s kinda what Adrienne was about. I don’t think there’s one of us who’d be here tonight if they accepted the values of the culture around us. Depending on our backgrounds we stayed with Yiddish or we came to Yiddish not only because Yiddish expresses who we are, but because it positively screams who we are not; as varied and multifaceted as Yiddish language and culture might be, it’s all founded on the idea of active opposition, of refusal to adopt beliefs that we know to be false and to take actions that we know to be wrong, me’ zol undz afile brenen un brotn, regardless of the pressures that are brought to bear. … And that refusal, that saying No to lies, is one of the things that Adrienne was best at.

In a time when “Orwellian” is in danger of losing all meaning from overuse, the loss of a spirit like Adrienne’s has never felt keener. zol zi hobn a likhtikn gan eydn…

***

Listen: Adrienne Cooper’s final CD Enchanted features Peace in the Streets as well as The Ballad of How the Jews Got to Europe, the wickedly funny song Michael Wex wrote for Adrienne’s show The Memoirs of Glikl of Hameln. Enchanted is essential listening for anyone seeking an insight into modern Yiddish song.

Learn: Professor Anita Norich will be making a rare New York appearance, talking on the Art of Translation at the Sholem Aleichem Cultural Center in the Bronx. (In Yiddish, followed by a musical program.) Sunday, Jan. 21, 1:30 p.m.

Commemorate: 70th yortsayt of Shloyme Mikhoels program at the JCC on the Upper West Side. Thursday, Jan. 18, 7 p.m. Free, but reservations are a must.

ALSO: 2018 is starting off with a bang in the Yiddish world. The Theater J Yiddish Lab series opens this month as well as a brand new initiative from cultural mover and shaker Josh Waletzky. His newly formed Yiddish Singing Society launched on Tuesday, Jan. 9 with a follow-up meeting on Jan. 16. The Singing Society seeks to “grow a new idiom of group singing” (hoo vah!) and focus on post-war Yiddish repertoire. (Jan. 16, 7 pm, 50 Rugby Road, Brooklyn) … If you’d rather be in the audience, you’re in luck, with a ridiculous slew of shows coming up: Thursday Jan. 11, the New York Klezmer Series marches into 2018 with the slightly ominous Klezmer Anschluss! (the name is iffy, the musicians are Rokhl-approved) … Jan. 13, 7 p.m. your last chance to see my new fave Goyfriend (a special collaboration between Sasha Lurje and Litvakus) at Golden Fest … or Jewlia Eisenberg and Jeremiah Lockwood’s eclectic Book of J (at the intersection of psalmody, Americana, and Yiddish songs of ghosts and police violence) 8 p.m. Barbes, Park Slope, Brooklyn. … And finally, the World Music Institute is presenting a three-show series this winter celebrating Jewish Contemporary Music. It’s a parve name for a history-making lineup featuring the music that changed my life: The Klezmatics, Hasidic New Wave, and John Zorn’s Masada. First up, the Klezmatics, Saturday, Jan. 20 at Town Hall. Special guests Fred Hersch, Holly Near, and that 10,000th maniac, Natalie Merchant.

Rokhl Kafrissen is a New York-based cultural critic and playwright.