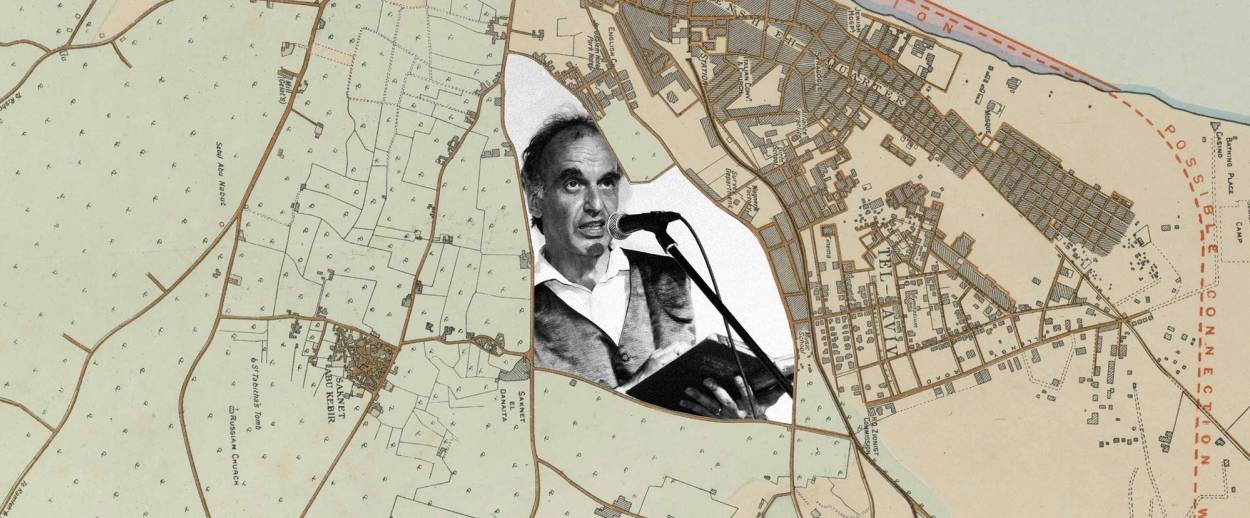

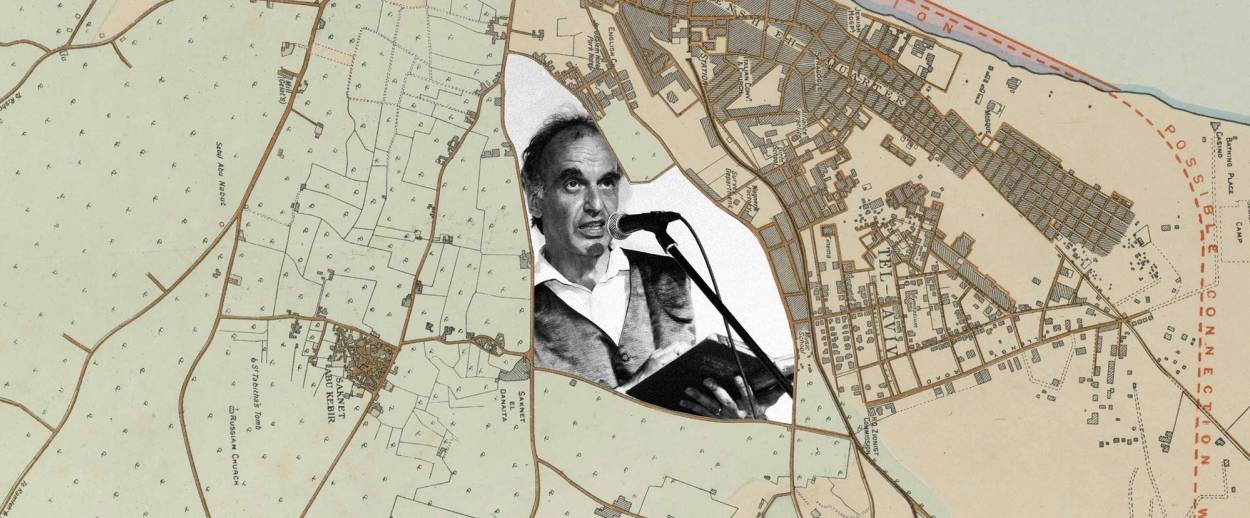

A Yiddish Purim Shpil in Tel Aviv

Rokhl’s Golden City: Eritrean detainees read Isaac Bashevis Singer, and the mother tongue meets the mother-land

One night, not too long ago, I found myself after hours and slightly bewildered, on the fifth floor of the infamous Tachana Merkazit, South Tel Aviv’s Central Bus Station. It’s the sprawling, half-empty New Brutalist folly that spawned a thousand metaphors. For a Yiddishist with a complicated relationship to the State of Israel, it seemed like a more than appropriate place to land.

Among the station’s endless levels of tattoo parlors, health clinics, shabby shops, and yes, an actual bat cave, sits Yung Yidish, the sexiest bus station Yiddish book-depot-cum–performance-space in Israel and, quite possibly, the world. After a Yung Yidish evening of lecture, song, and the best herring I’ve had in ages, we were reluctantly heading back to our temporary home at 33 Lilienblum.

Exiting the maze-like bus station, though, iz nisht keyn kleynikayt. Leaving turned into an informal tour led by David Serebryanik, a young Russian piano virtuoso with giant hands and a wild head of hair to make Beethoven himself yank out his ear horn and weep with envy. With an unlit cigarette hanging off his lip, Serebryanik, the house accompanist at Yung Yidish, smiled and gestured at what could easily be the setting for Night of the Living Dead: Aliyah. “Isn’t it fantastic?” Reader, it was indeed fantastic.

After a 24-year interlude, I was finally on my second visit to Israel. This time, with my according-to-the-laws-of-Joseph-Smith-and-Tahiti gay husband Shane Baker. Shane and I were that evening’s entertainment, welcomed warmly by legendary Yung Yidish balebos Mendy Cahan. My contribution to the program was a marginally interesting talk on the death of the klezmer revival. Shane, on the other hand, enchanted the audience in a lacy white dress and glittery silver lips, appearing as his new drag character, Miss Mitzi Manna from Manhattan. Though our trip was too short to make Purim in Tel Aviv—“the City of Purim”—Miss Mitzi Manna was an excellent forshpayz (appetizer).

Yung Yidish is just one of the hubs of Yiddish Tel Aviv. Where Yung Yidish is your nighttime haunt for theater, poetry, and endless dimly lit l’chaims (seriously, the lighting in there is amazing), 48 Kalisher Street, home of the Arbeter-ring (now officially part of the Beth Shalom Aleichem) is its more sober, but just as cozy, daytime address. New York-born director Bella Bryks-Klein keeps 48 Kalisher humming with a full schedule of activities. Bella sees her work in the Bundist tradition, melding heymish and high culture. Her bi-monthly kultur krayz (cultural circle) features academic lectures and music as well as badekte tishn.

The Arbeter-ring svive is a who’s who of the older Tel Aviv Yiddish literati. I sat a few seats away from poet Rivka Basman Ben-Hayim at the kultur krayz luncheon Shane and I attended. This particular session was in honor of Yiddish doctoral student Yaad Biran, celebrating the publication of his new book of short stories (in Hebrew, with a Yiddish tam), Lakhn mit Yashtsherkes.

Yaad is also the conductor of a number of Yiddish city tours. We took his Yiddish Tel Aviv tour Yidish af di gasn (Yiddish in the streets), a truly worthwhile experience in itself, but especially worthwhile for introducing me to the Migdal Shalom wax museum and the gruesome tableaux that terrorized a generation of young Zionists. (Seriously, if someone wants to pay me to move to Tel Aviv and write a book about the Migdal Shalom wax museum please contact me immediately.)

The following night at the Beth Shalom Aleichem (the gorgeously un-heymish new Yiddish cultural center on Berkovitch) one of Yaad’s texts was presented as part of their most excellent Purim Shpil. Yaad’s contribution was Haman’s a mesire (Haman’s Denunciation). As Yaad explained it, in traditional Purim shpils, this was a text where authors could use the voice of Haman to satirize hot-button issues of the day. In this case, Yaad quite cleverly uses the text to portray Haman as a crusader against Yiddish and Yiddishists:

,ס’איז פֿאַראַן אַ שפּראַך

,הער מלך, בין איך אײַך מגלה

צעזייט און צעשפּרייט איז זי

.צווישן די שפּראַכן אַלע

(There is a language, my king, spread out among all the languages…)

Haman urges the king to call for the death of Yiddish and in a final twist, thinks better of it, proclaiming the language already dead. Yiddish, of course, lived to see another day.

Just as Haman was unable to fulfill his wicked plan against the Jews, so the many who sought to bury Yiddish have seen their wishes thwarted. It was quite an experience to see the Purim Shpil (mostly in Yiddish) play to a beyond-capacity house at Beth Shalom Aleichem. The position of Yiddish in Israel is complicated in ways we don’t have to confront here in New York, something I knew going in, and yet… I felt a stealthy hopefulness in Tel Aviv that I don’t often feel at home.

At the beginning of the week, I had coffee with my friend Anshel Pfeffer to celebrate the imminent publication of his terrific new Netanyahu bio. Anshel is famously brutally blunt when it comes to Israel-Diaspora relations as he sees them. So I was naturally intrigued when he told me there was one area where he felt Diaspora activists were making an impact on Israeli policy and energizing Israeli activists. Did I, a famously brutally bleeding heart mushy pro-Diaspora, anti-Bibi liberal want to come with him and see for myself? I sure did. And so I ended my week in Israel speeding away from the cramped bustle of shtetl Tel Aviv into the pocket desert that is the Negev, destination Holot detention center.

What I saw in Holot was both hopeful and heartbreaking. Heartbreaking to talk to men whose lives are being used as props by a flailing regime. (You can read Anshel’s reportage here.) But hopeful, to see that these men had not been forgotten. We were surprised to find an afternoon barbecue for the detainees in progress, organized by volunteers from an Israeli group called Tikve b’Holot. Little kids wandered around and dogs chased happily after Frisbees.

As we surveyed the unlikely party, a lone sagging bookcase caught my eye, stuffed as it was full of books whose relevance seemed only to be that no one else wanted them anymore. Among the mishmosh of battered titles was a Hebrew language book about the Slonim partisans and an English language edition of Bashevis’s Gimpl the Fool.

I can’t fault whatever well-meaning volunteer thought an Eritrean detainee might be interested in Bashevis, and hey, you never know. But seeing that sad heap of books nudged something to the front of my mind. More than any other moment in time, the Jewish people are drowning in old books, in all languages, and no one knows what to do with all of them. (Well, at least one person has figured it out—wander into a chic spot on Montefiore Street called Notbook, and you can find all kinds of Jewish books that have been repurposed into artisanal journals and notebooks. Interestingly, the only kind of book you can’t find being repurposed in Notbook is Yiddish.)

Both 48 Kalisher and Yung Yidish are stuffed with Yiddish books that needed a new home, a circumstance not unlike that in the United States. Here, though, the National Yiddish Book Center has made its mission to collect, house, scan and sell old Yiddish books and has fulfilled that mission to an almost-superhuman T.

After seeing how much room these books take up in spaces that were never meant to house giant, aging libraries an #UnpopularOpinion (meant with no disrespect to the work being done by my book rescuing friends) began scratching at my brain. What if we didn’t worry so much about the books? What if we recognized the urgent need to fund and house the people doing the work? What if… what if we cared more about making new Yiddish readers than about saving old books that have already been effectively saved? Maybe I’ve been infected by the KonMari madness, but as much as I love and respect books (and the people who lovingly take them in), I also believe our books must serve us, not the other way around. And the media’s focus on “saving” Yiddish books—instead of investing in literacy, and the people doing the hard work of cultural transmission—troubles me.

It’s tempting to read Yung Yidish’s location in the Tachana as lying “hintern ployt”—the remotest part of a Jewish cemetery reserved for the disreputable dead. Indeed, that’s the angle journalists usually take when writing stories about Mendy and Yung Yidish, emphasizing his work single-handedly, futilely “reviving” the language and guarding the corpses of a dead culture. But, I’d suggest that YY’s location in the bus station is a sign of lively, connected resistance, rather than noble decay. Those piles of books, while important and, let’s admit, photogenic, do precious little of the ceaseless work of teaching, scheduling, crooning, welcoming, and fundraising taking place at Yung Yidish (and the Arbeter-ring). At the end of the day, no amount of books, or virtual resources, can ever replace the warmth and fellowship of the face to face encounter. And I can’t wait to go back.

Yiddish in Tel Aviv (and Beyond)

Subscribe: Bella Bryks-Klein’s email list, Vos Ven Vu is an essential key to Yiddish Tel Aviv (and beyond). Send an email to Bella asking to subscribe: [email protected]

Watch: Gimpl the Fool is popping up everywhere. On March 13 Yung Yidish hosts the Nefesh Theatre production of Gimpl Tam (in Yiddish). You can also contribute to Yung Yidish and its multifarious projects here.

Donate: There are a few names in Israel synonymous with Yiddish: Avrom Sutzkever, revered poet of the Vilne Ghetto, is one them. Right now a group of filmmakers, including Sutzkever’s granddaughter, Hadas Kalderon, is fundraising to complete a documentary about his amazing life.

Parade: I’d give my left arm to be in Israel for Purim this year. But if you’re lucky enough to be there, go check out the historic Adloyada Purim Parade in Holon. Originally a Tel Aviv tradition, the parade celebrates the commandment to drink until you can’t tell the difference between Mordecai and Haman. Interestingly, the name Adloyada is relatively new and was coined by none other than Y.D. Berkowitz, son-in-law of Yiddish writer Sholem Aleykhem (and namesake of the street on which the new Beth Sholem Aleichem now sits.)

ALSO: Please note that the omission of any Israeli Yiddish group or organization should be read only as a function of my too short time in the land. For even more information about Yiddish in Israel take a look at the official website of the National Authority for Yiddish Culture. … One of the most personally heart-wrenching moments of my trip to Israel was meeting up with my dear friend Magda Kozlowska at 48 Kalisher. Magda is a non-Jewish scholar of Yiddish in Poland and speaks a more beautiful Yiddish than I can ever dream of. She’s also from Kalisz, which made our encounter even more poignant. Magda embodies the forward-thinking young generation in Poland which seeks connection to Jews and history. She reminded me why, in charged moments like these, it’s important for American Jews to travel to Poland and meet Poles who care about the same things we do. More here in Jonathan Ornstein’s excellent New York Times opinion piece. … If you can’t be in Israel for Purim, you can catch Miss Mitzi Manna (Shane Baker) at the (belated) Purim Simkhe at the Sholem Aleichem Cultural Center, Sunday, March 4, 1:30 pm, with music by fiddlers extraordinaire, Deborah Strauss and Jake Shulman-Ment, 3301 Bainbridge Avenue, Bronx. … And if you’re really, really lucky, you’re in Miami for the first ever YI Yiddishfest, March 1-4… .hot a freylikhn!

Rokhl Kafrissen is a New York-based cultural critic and playwright.