The Diary of Anne

The very private non-Holocaust-related life of Anne Frank: teenage manga girl, tampon-marketer, European traveler, and emblem of the twin evils of war and intolerance—and the Japanese ‘culture of apology’

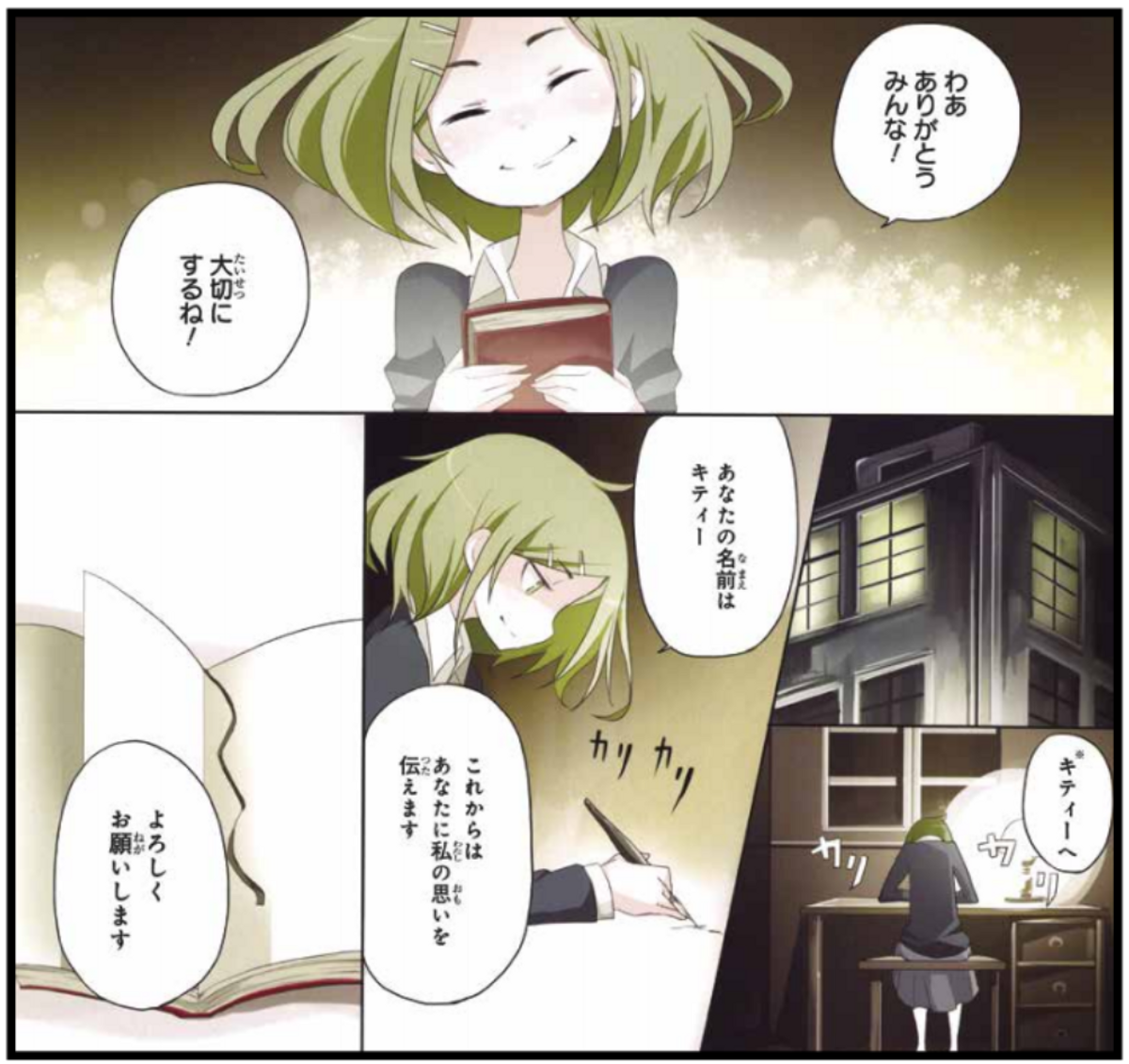

Erika Kobayashi, a young Japanese writer and manga artist, was at a ramen restaurant in midtown Manhattan eight years ago when, as she put it, “Anne Frank came out of nowhere.”

The encounter, which transpired over bowls of Nagasaki noodles, began when an elderly man seated nearby struck up a conversation. His name was Joel. He was 73. His hair was white, his bearing large, and his demeanor introspective. He took a liking to Kobayashi and, disarmed by the moment, revealed something he said he had never told anyone before.

“He was an American soldier in the Korean War,” Kobayashi recalled, “and he stayed in Japan sometimes because the army base was there. At that time he was really young, and he told me he played around with lots of women. Every night he slept with different Japanese girls.” It was 1953. The girls were prostitutes and they wanted out. Life in Japan was hard as the country tackled the arduous ongoing challenges of postwar recovery and reconciliation.

Joel said that many of the girls would cry in the middle of the night. “They would ask him, ‘Why won’t you become my boyfriend, why won’t you bring me back to America?’” Joel told Kobayashi.

Joel remembered one particular woman—a plain-looking girl with glasses whom he indelicately described as “the ugliest of all.” She cried in the middle of the night too. But Joel was fond of her.

“He didn’t understand why she was crying,” Kobayashi said. “And he suddenly realized that in the bed next to him she was reading Anne Frank’s diary. That was why.”

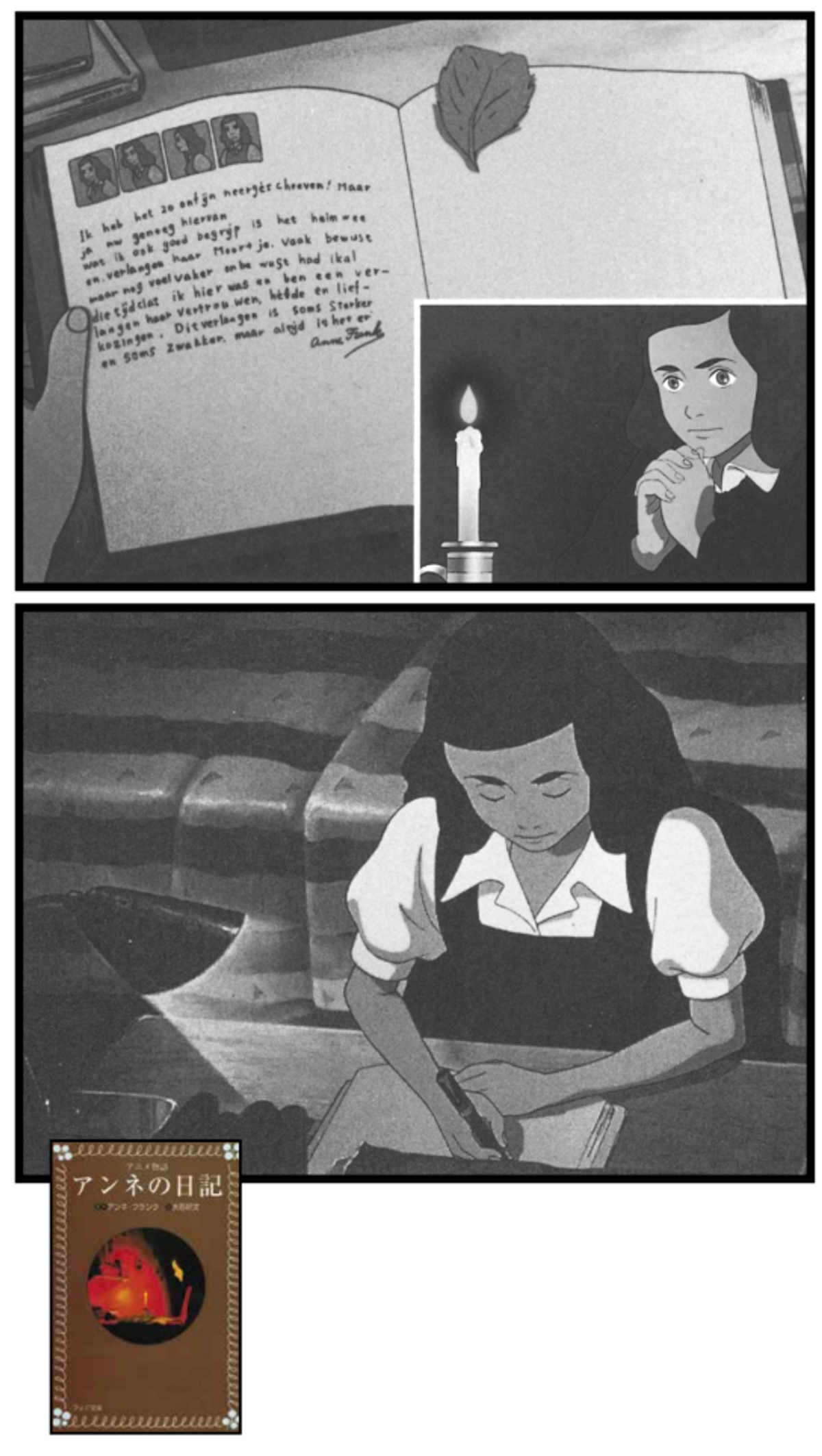

“It’s an example of how popular the diary was and also how moving the diary was to every woman in any situation,” said Kobayashi, who a few years after her encounter with Joel traveled to Europe to retrace the footsteps of Anne Frank’s life and wrote a well-received memoir about the experience. She’s not alone in her interest. Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl was translated and published in Japan in 1952. Within a year it became a best-seller, and it is still widely read there. Nearly 6 million copies of the book have been sold to date in Japan, where sales have been exceeded only by those in the United States.

***

By now, Anne Frank’s story has been told in Japan on many platforms—in manga and animated film, on television and on stage in both dramatic and musical forms. The diary has inspired a steady flow of Japanese tourists to Amsterdam, where more than 30,000 of them visit the Anne Frank House each year. But why?

The popularity has little to do with interest in Judaism, let alone with the Holocaust. It is Anne’s personal story that draws most readers in, particularly young female readers. The diary’s rich description of teenage emotions resonates unusually strongly with 13-, 14-, and 15-year-olds in Tokyo, Osaka, and Hiroshima—despite the wholly dissimilar circumstances of their lives.

“More than being Anne Frank the Holocaust victim she’s Anne Frank the teenager here,” said Makiko Takemoto, a Japanese scholar who specializes in modern German history. “The fact that Anne was killed as a result of the Holocaust is rather forgotten.”

“Anne Frank is not even Anne Frank for most people,” said Ran Zwigenberg, an Asian-studies specialist at Penn State University who has written about Japanese perceptions of the Holocaust. “She’s just ‘Anne,’ a figure of femininity and an early teenager, and everybody learns about her very private non-Holocaust-related life.”

Zwigenberg pointed out that the diary was one of the first books in Japan to talk openly about menstruation. “Drawing on this image, a Japanese feminine-hygiene company actually made a tampon called Anne Tampon, and ‘Anne’s day’ became a euphemism for a woman’s period.”

I met with Zwigenberg this summer at Hiroshima City University’s Peace Institute, where he was a visiting scholar and where Takemoto is based. It was July, just a few weeks before Japan would mark the 70th anniversaries of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings and its surrender in World War II. These were hugely important events in Japan, where wartime misdeeds, suffering, guilt, and blame continue to affect government policy.

For months a planned anniversary statement by Prime Minister Shinzō Abe preoccupied the Japanese media. At issue was whether and how Abe would ask forgiveness for his country’s wartime aggression.

Zwigenberg, an Israeli who speaks Japanese fluently, said there is “a culture of apology” in Japan where expressions of remorse have real significance. Japan’s relations with its Asian neighbors, particularly China and South Korea, would warm or chill on the strength of Abe’s syntax. Would he say “deep remorse” and “heartfelt apology”? Would he acknowledge Japan’s wartime “aggression” and “colonial rule”?

As it turned out, Abe used all those words, but he also suggested that, after 70 years, enough is enough. “We must not let our children, grandchildren, and even further generations to come, who have nothing to do with that war, be predestined to apologize,” Abe said.

Accepting responsibility for wartime behavior, articulating guilt and remorse—these are essentially ethical questions, and they have long nettled Japan’s leaders. This also helps to explain the appeal of Anne Frank there.

“The Jews as a whole everywhere are usually a foil to talk about something else—especially in a place like Japan, where there are no actual Jews,” Zwigenberg told me. He and others have argued that by embracing Anne Frank, Japan—consciously or not—is soft-pedaling history. “It has … helped the Japanese reconceive themselves as victims of the war,” according to scholars David G. Goodman and Masanori Miyazawa. In their book Jews in the Japanese Mind, they write that “the popularity of Anne Frank’s Diary in Japan has not necessarily translated into an understanding of the Jewish experience.” Rather, it “has contributed to the tendency to generalize the war experience and avoid coming to terms with the specific problems of wartime responsibility and guilt.”

In other words: Japan reads Anne Frank, some say, to feel better about itself.

***

Sayaka Hanamura is a Japanese actress who has portrayed Anne Frank on stage. She is a thoughtful woman who by vocation has reflected a lot about Anne Frank and Japan.

“It’s complicated,” she said, when I asked her about equating Jews and Japan as victims of World War II. “Japan was a victim of the atomic bomb, but Japan was also an ally of Germany. So, when it comes to the topic of Jewish victims, it’s very difficult.”

Hanamura said most Japanese understand Anne Frank’s diary as a message of peace. “We do share a common awareness with Jewish people that we don’t want to repeat the war,” she said. “But I do feel there are issues of Japan turning a blind eye to the war. So, when I perform Anne Frank, I don’t want to do so irresponsibly. Although Japan is the only country that experienced the A-bomb, that does not offset what the Japanese army did in World War II.”

There are several organizations and even a church in Japan that honor Anne Frank and interpret her diary as a manifesto against the twin evils of war and intolerance. Akio Yoshida is deputy director of the largest of them, the Holocaust Education Center, located in Fukuyama City, not far from Hiroshima.

“Our center’s main hope is for the Japanese people to know the story of the Holocaust,” Yoshida told me when I visited several years ago. “We try to tell it to them through Anne Frank, the story of a girl who suffered so much just because she was born a Jew.”

Yoshida said the center takes care not to equate the Holocaust with the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. “The two are different. The Jews were not fighting. They were discriminated against because they were Jewish. It’s not the same, and Japanese should know about the Holocaust so they can differentiate it from the Hiroshima event.”

The center is affiliated with a Christian church that is situated along a winding road on the heights overlooking Osaka. Both center and church were founded by Makoto Otsuka, a clergyman who took up the mantle of Anne after a chance meeting with Otto Frank during a 1971 visit to Israel. The church, which features a statue of Anne as well as a stained-glass Star of David, is called “Anne’s Rose Church.” A flower donated by Otto Frank grows in the facility’s garden.

I went there recently with Karen Kanazawa and her mother, Mie. Both are Japanese—the family lives in the nearby city of Kobe—and both had heard about Anne Frank in school. They read The Diary of a Young Girl together a few weeks before the visit. “I researched about Anne Frank and found out that she passed away when she was 15 years and 8 months old, which is exactly how old I am right now,” Karen said.

Seiji Sakamoto, the church reverend, showed us around the sanctuary, which displayed a miniature mock-up of Anne Frank’s Amsterdam hideout, a silver baby spoon used by Anne that was contributed by her father, and a glass-enclosed first edition of the 1952 Japanese translation of the diary.

“When I read the diary I feel like I’m reading the Bible,” Sakamoto said.

After the tour, Karen and Mie sat down with Sakamoto and shared their thoughts about Anne and her diary. For Mie, the diary was about “the growth of a bright teenage girl with a shining heart.” She told Sakamoto she was particularly struck by diary passages about Anne’s sometimes contentious relationship with her mother. “I wonder if Karen might have the same negative feelings about me,” she said.

“No, no never,” Karen assured her, “although I was curious about Anne’s anger against her mother and her rebelliousness.”

Karen said she admired the strength of Anne’s personality. “Where did the confidence come from? Anne said she was never jealous of her sister, Margot, even though Margot was treated so well by the adults. If it was me, I would have felt jealous.”

I was struck by the absence of questions or comments from Karen and Mie concerning the Holocaust. The psychology of Anne the teenage girl is what fascinated them, her emotions and angst and intelligence and strength of mind.

That kind of thinking bothered Machiyo Kurokawa, a survivor of the Hiroshima bombing who wrote three books about Anne Frank. I spoke with Kurokawa a year before her death from leukemia in 2011. She died at 81, the same age Anne Frank would have been had she, like Kurokawa, survived the war.

Kurokawa’s passion for Anne Frank began in the early 1950s when she first read the diary. She would go on to visit the Anne Frank House and attend Anne Frank symposia. She also traveled to Bergen-Belsen, where Anne Frank died, and to Auschwitz. “I’ve been to Auschwitz many, many times,” she once told me.

“I feel the Japanese people need to know about the Holocaust,” she continued. “I think the sufferings of the Jewish people cannot be compared to what the Japanese people went through. Yes, we experienced the atomic bomb. But this was one event. The Jews have a long history of suffering.”

Fumiko Ishioka, director of a Holocaust education center in Tokyo, was a good friend of Machiyo Kurokawa. Ishioka delivered the eulogy at Kurokawa’s funeral.

“Machiyo’s work was important for letting people know why Anne Frank died,” she told me. Machiyo Kurokawa, she said, rejected sentimental readings of the diary. “She was critical of the way some Japanese almost ‘beautified’ Anne’s death. Machiyo made sure young people understood Anne didn’t die ‘pretty’.”

Machiyo Kurokawa’s books were among 300 or so Anne Frank-related volumes, including the diary, that were vandalized in Tokyo libraries in early 2014. The incident made international news and raised concerns that the nationalist policies of Prime Minister Abe had fostered prejudice and anti-Semitism. Police arrested a 36-year-old unemployed man who was described as mentally unstable. The Japanese press reported that in a confession the man said he was motivated by the belief that Anne Frank’s diary was a hoax.

The affair embarrassed the Abe government, and in March 2014, during a previously scheduled trip to The Hague, Abe visited the Anne Frank House to express his regrets.

In January of this year, during a trip to Jerusalem, Abe visited Yad Vashem, Israel’s memorial to victims of the Holocaust.

“Today I have learned how merciless humans can become when they single out a group of people and make that group the object of discrimination and hatred,” Abe said. “In March, last year, I visited the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam. Today I find myself fully determined. Ha-sho’a le’olam lo od. The Holocaust, never again.”

Robert Rand is the author of several books, including My Suburban Shtetl: A Novel about Life in a Twentieth-Century Jewish American Village. His reporting in Japan was supported in part by the Fulbright Program and the Asian Cultural Council.