Out of Focus

Curator Maya Benton discusses how the image of shtetl life we’ve gotten from Roman Vishniac is a distortion not only of life in the Old World but of the photographer’s own oeuvre

In this weekend’s New York Times Magazine, I profile the work of a young curator named Maya Benton, who has made an extraordinary discovery in the collection of legendary photographer Roman Vishniac, the man credited with creating the last photographic record of Eastern European Jewry before it was destroyed in the Holocaust. As Benton learned, Vishniac released for public consumption only a small selection of the images he took—primarily those that advanced a nostalgic impression of prewar Eastern European Jewish life as “abjectly poor in its material condition, and in its spiritual condition, exaltedly religious,” according to the flap copy of his first book. In this narrated slideshow, Benton walks us through a handful of her favorite Vishniac pictures, revealing how his curating job not only skewed our understanding of this lost world, but also limited the public recognition of Vishniac’s own vast talents.

Vishniac was, in fact, part of what might be characterized as the unwitting, well-intentioned nostalgia industry of the postwar decades—one including but not limited to Abraham Joshua Heschel, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Margaret Mead and her team, Leo Rosten, the editorial staff of Mad Magazine, countless museums, communal leaders, synagogue and organizational staffs, and generations of parents who exhorted their children to revere what has turned out to be a patronizingly provincial notion of prewar Jewish life. In the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust, this manufactured idea of the “shtetl” may have aided in the unavoidable, overwhelming grieving process. But 60 years later—with countless memorials, annual programs, school curricula, books, films, musicals, a federally mandated Holocaust museum in the nation’s capital, and more—do we still need to rely on a caricature in order to be able to commemorate? If anything, the victims of the lost world of Eastern European Jewry deserve to be remembered in the fullness of the life they led.

So, why won’t contemporary Jews give up the “shtetl” fantasy? Have we become nostalgia addicts?

“Many American Jews don’t want to change their perception of the shtetl,” Eddy Portnoy, who teaches Yiddish literature and culture at Rutgers, told me. “The distinction between them and their grandparents—naïve, uneducated, unsophisticated—is still what makes them feel modern.” Ah, the irony: By misrepresenting our ancestors as backward and unsophisticated, American Jews have managed to create communities that are less Jewishly diverse—and consequently, in some real ways, less sophisticated—than the fabled shtots and dorfs and shtetls of Eastern Europe. Indeed, many who have tried to engage creatively with Jewish tradition have found themselves strangled by the obsession with a misremembered past. “Often when I play in synagogues or Jewish Community Centers, or at functions like weddings, the music is there to act as a signifier of Shtetl Judaism,” said Ben Holmes, a trumpet player with several years of experience in the klezmer world. “There’s a huge temptation to take the easy path and go straight for nostalgia, and relatively little incentive to try to create something new.” In some ways, nostalgia has become an artificial opiate, one preventing the American Jewish body from naturally producing the kind of vital new culture necessary for its survival.

Given the robust organization of the Jewish philanthropic world, it is worth noting that the International Center of Photography, which is acquiring the collection, has struggled to fundraise for the Vishniac project. (The primary gift thus far has been from one of its own trustees, Andrew Lewin, who stepped up to the plate with a donation that he intended as an endowment; it has already been dipped into for operational costs.) As a result, it will be at least another year and a half before ICP has a publicly accessible archive, which is the necessary first step to putting together an exhibition and then book-length catalogue of Vishniac’s best published and unpublished work. This delay isn’t just a pity; it is an embarrassment—and a challenge. The Vishniac archive is indeed, as I wrote, a litmus test of the future of Jews in America: Are we ready to give up our shtetl nostalgia, in exchange for something more real?

Click here to view slideshow with audio commentary.

Click below for audio commentary by curator Maya Benton, as interviewed by Alana Newhouse.

[audio:https://www.tabletmag.com/wp-content/uploads/images/vishniac/Vishniac1.mp3]

Left: Jewish schoolchildren, Mukacevo, ca. 1935-38, cropped for cover of To Give Them Light. Right: Uncropped version.

CREDIT: Roman Vishniac.

© Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy the International Center of Photography

Click below for audio commentary by curator Maya Benton, as interviewed by Alana Newhouse.

[audio:https://www.tabletmag.com/wp-content/uploads/images/vishniac/Vishniac2.mp3]

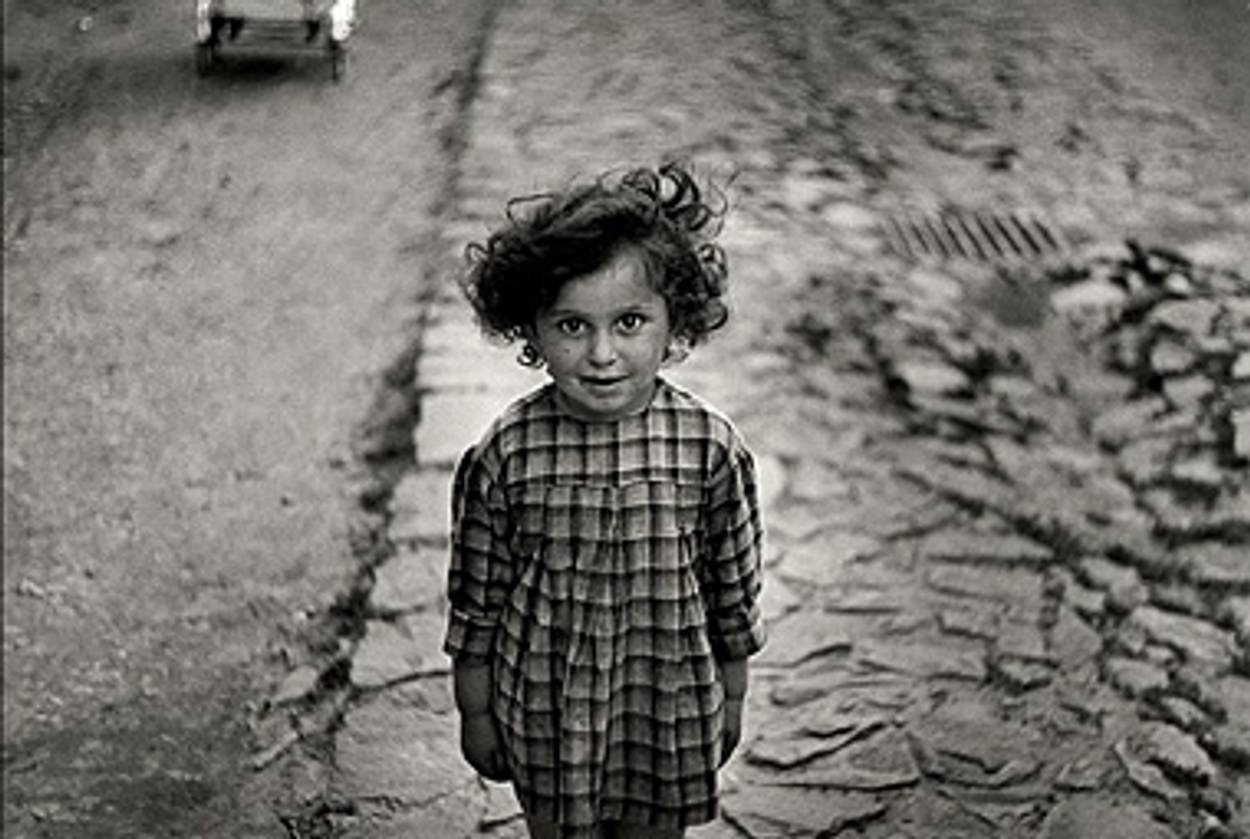

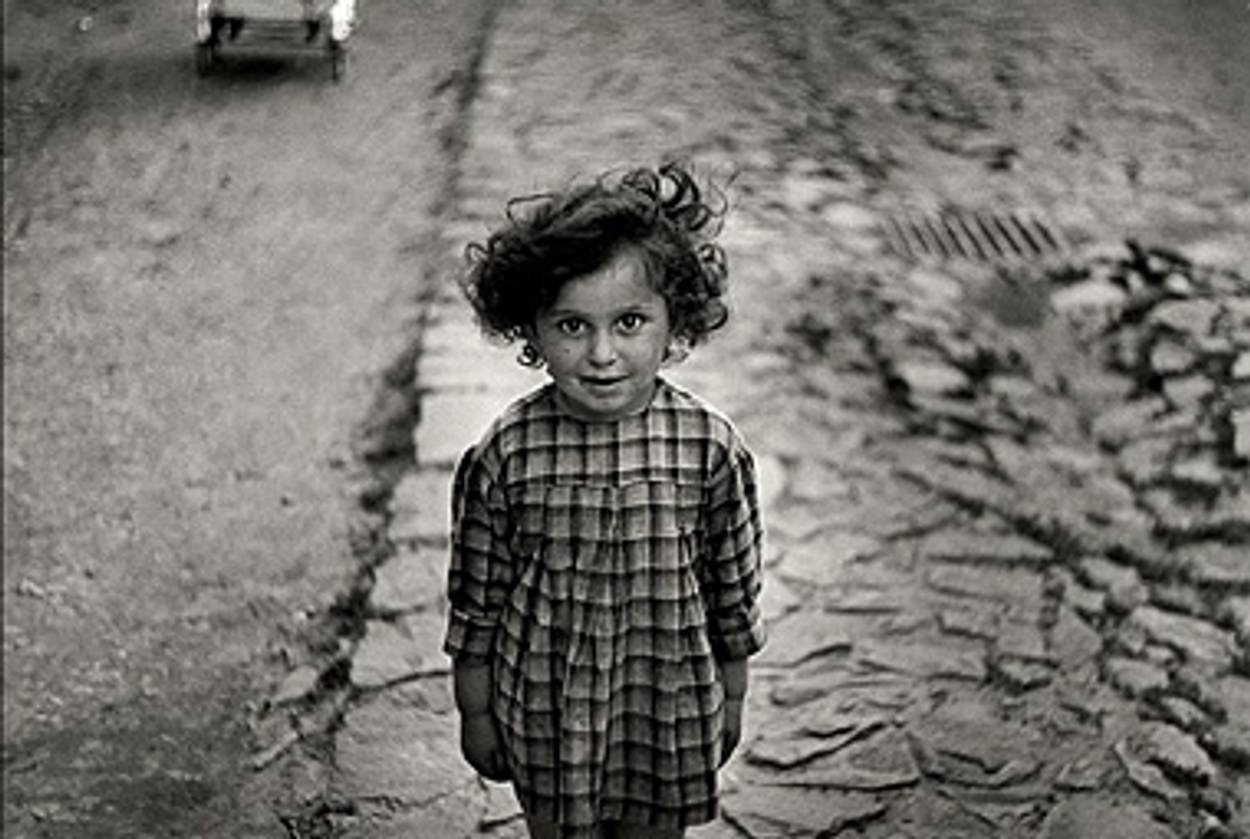

Exiles in limbo, Zbaszyn camp, Poland, November 1938. Unpublished.

CREDIT: Roman Vishniac.

© Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy the International Center of Photography

Click below for audio commentary by curator Maya Benton, as interviewed by Alana Newhouse.

[audio:https://www.tabletmag.com/wp-content/uploads/images/vishniac/Vishniac3.mp3]

American Joint Distribution Committee food distribution office in the Displaced Persons Camp, Germany, 1947.

CREDIT: Roman Vishniac.

© Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy the International Center of Photography

Click below for audio commentary by curator Maya Benton, as interviewed by Alana Newhouse.

[audio:https://www.tabletmag.com/wp-content/uploads/images/vishniac/Vishniac4.mp3]

Left: Egress from the cellar dwellings, Krochmalna Street, Warsaw, ca. 1935-38. Right: Children in a cellar dwelling, Krochmalna Street, Warsaw, ca. 1935-38. Both unpublished.

CREDIT: Roman Vishniac.

© Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy the International Center of Photography

Click below for audio commentary by curator Maya Benton, as interviewed by Alana Newhouse.

[audio:https://www.tabletmag.com/wp-content/uploads/images/vishniac/Vishniac5.mp3]

Left: Carrier of heavy loads, Lodz, ca. 1935-38. Right: Exhausted. A carrier of heavy loads. ca. 1935-38. Both unpublished.

CREDIT: Roman Vishniac.

© Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy the International Center of Photography

Click below for audio commentary by curator Maya Benton, as interviewed by Alana Newhouse.

[audio:https://www.tabletmag.com/wp-content/uploads/images/vishniac/Vishniac6.mp3]

Haberdashery in the open market, Warsaw, ca. 1935-38. Unpublished.

CREDIT: Roman Vishniac.

© Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy the International Center of Photography

Click below for audio commentary by curator Maya Benton, as interviewed by Alana Newhouse.

[audio:https://www.tabletmag.com/wp-content/uploads/images/vishniac/Vishniac7.mp3]

Students in a Jewish work-settlement, Werkdorp Wieringen, The Netherlands, 1939. Unpublished.

CREDIT: Roman Vishniac.

© Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy the International Center of Photography

Click below for audio commentary by curator Maya Benton, as interviewed by Alana Newhouse.

[audio:https://www.tabletmag.com/wp-content/uploads/images/vishniac/Vishniac8.mp3]

Boys in gymnasium, New York, ca. 1941-45.

CREDIT: Roman Vishniac.

© Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy the International Center of Photography

Click below for audio commentary by curator Maya Benton, as interviewed by Alana Newhouse.

[audio:https://www.tabletmag.com/wp-content/uploads/images/vishniac/Vishniac9.mp3]

Copulating Mexican bean beetles (virgin print), ca. 1940s.

CREDIT: Roman Vishniac.

© Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy the International Center of Photography

Click below for audio commentary by curator Maya Benton, as interviewed by Alana Newhouse.

[audio:https://www.tabletmag.com/wp-content/uploads/images/vishniac/Vishniac10.mp3]

Top: Fish is the favored food for the kosher table (boy with herring), ca. 1935–38. Bottom left: Weaver’s studio, Lask, Poland, ca. 1935-38. Bottom right: The general store, Poland ca. 1935-38. All unpublished.

CREDIT: Roman Vishniac.

© Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy the International Center of Photography

Alana Newhouse is the editor-in-chief of Tablet Magazine.

Alana Newhouse is the editor-in-chief of Tablet Magazine.