Bound for Glory

Harry Houdini exhibited two very different public faces—master of escape and anti-mystical firebrand—that were united by his Jewishness

At the heart of “Houdini: Art and Magic,” an ambitious new exhibit that opened last week at New York’s Jewish Museum, is a disappearing act: a piece of the great escapologist’s Jewishness is missing.

This is not entirely surprising. Since his death in 1926, Houdini has attracted many explainers, but few have grappled well with what can be seen as the two sides of the escape artist’s Jewish identity. The first is well-known: his popular death-defying theatrical acts, which represented freedom from his father’s financial failure as well as a more general liberation from the limitations immigrant Jewish life. But there is also Houdini’s less-known second act as a debunker of a mystical group known as the Spiritualists, a crusade that shared much with Emma Goldman’s fiery political tirades and that proved the boundaries of Jewish entertainers in the face of American anti-Semitism.

The first several chapters of Houdini’s life fit easily into the familiar coming-to-America immigrant story. Born in Budapest, Houdini (né Erich Weiss) arrived in Appleton, Wisconsin, with his mother and four brothers in 1878, at age 4; his father, a rabbi, had secured a job. By 1882, the congregation decided it wanted a more modern, English-speaking leader, and the Weisses (by now there were six children) moved, first to Milwaukee, and, in 1887, to New York.

Houdini worked as a newsboy and in a tie factory alongside his father, who died of cancer of the tongue in 1892. “Such hardships and hunger became our lot … the less said on the subject the better,” he later said.

He and his brother performed as The Houdini Brothers—the name an homage to the French conjurer Jean Eugene Robert-Houdin, whose act he would later debunk. The Houdinis polished their act at dime museums and possibly at the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition. By 1899, Houdini was a solo star in vaudeville. He began a five-year tour in Europe, where he became an international celebrity.

The eminent authors of the essays in the gorgeous exhibit catalog published by Yale University Press make a good case for seeing Houdini’s escape acts as aspirational, for Jews and for all Americans of the era. The historian Alan Brinkley writes that Houdini was “a symbol of escape … physical power … success and upward mobility.” Kenneth Silverman, Houdini’s most respected biographer, notes that the escape artist’s Jewishness made him “a symbol of freedom.”

But a casual look at the props Houdini used makes it difficult to explain his escapes as only representing power and success; they also hint at what was at times an adversarial—even hostile—relationship with his audiences. In much the same way that white performers parodied African Americans by wearing blackface, Houdini parodied criminals, freaks, and the mentally insane by wearing their costumes and using their artifacts. Houdini sometimes went to great lengths to prove himself as an almost real criminal, allowing himself to be strip-searched by the police. But the fact that audiences were ultimately able to root for him turned on the distance between him—a celebrity—and those nameless deviants. The hero always escaped from his escapes, albeit sometimes breathless, and other times injured.

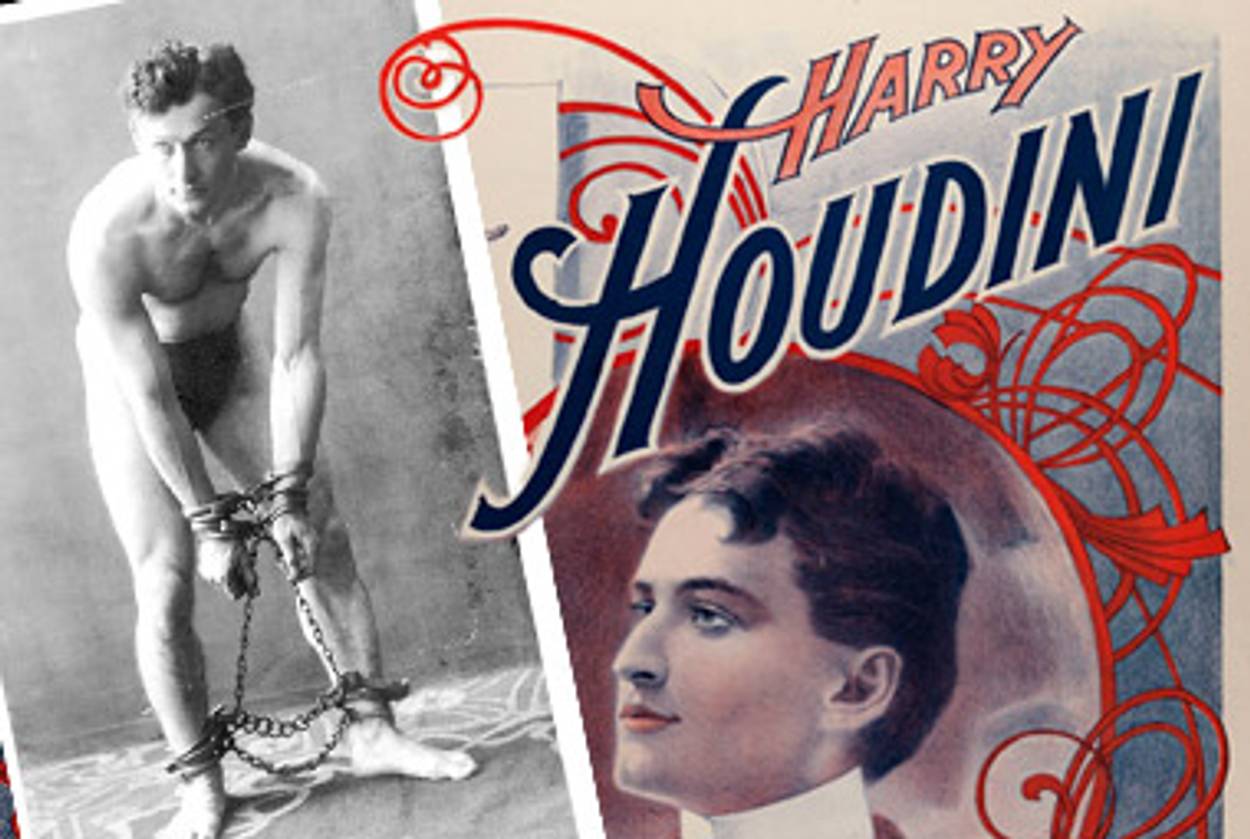

Houdini was aware of the blood-lust in his audience, whom he referred to at least once as a mob. They were always trying to expose him, to tell how he did it, to sue him or to imitate him. Houdini mostly won on stage. Besides the exotic costumes—thick, long ropes, shackles, or leather straitjackets he wore onstage as proof of his imprisonment—Houdini performed either nearly nude, like a strong man, or in a tuxedo, like a male Marlene Dietrich. Some of the photos of him brim with barely contained violence, such as the one where the escape artist in a loincloth and chains is poised to dive off Harvard Bridge surrounded by dark-suited, hatted policemen with billy clubs in their belts.

As Houdini reached middle-age, he began to feel confined by his escape acts. Every time he writhed free from one container, he had to design a more confining one: locked handcuffs, straitjackets suspended high above city streets, glass boxes underwater, milk-cans sealed shut, buried coffins, piano cases, jail cells of murderous criminals, even a Siberian prison. Around the time of World War I, which also coincided with his mother’s death, Houdini began to explore escapes besides the ones he had pursued on stage. He became the first man to fly an airplane in Australia. He starred in silent films, and he founded his own film production company.

Houdini’s mid-life crisis appeared to arise at least in part from an unresolved tension in his Jewish past. The man whose father was a rabbi and a poet seemed to long for a more erudite legacy than the one that had made him a celebrity and was based on derring-do. Thus during this period, he wrote (or at least oversaw) books exposing the failures of earlier generations of magicians. He amassed an enormous theater archive, which he donated to Harvard. “I come from a race of students. I am not entirely illiterate and I do read and study,” he once said.

And then in 1920, Houdini found a satisfying second act: demystifying Spiritualism, a cult many Americans turned to after losing their loved ones in World War I. From being an escape artist, Houdini became an exposer of psychics whom he considered charlatans because they used trickery to pretend to commune with the dead—as opposed to merely pretending to escape. This was not just Houdini’s competitive spirit. What he did was entertainment. Spiritualism was magic in supernatural clothing.

Like many Jews of his generation, Houdini had until this moment seemed to stave off anti-Semitism by becoming an entertainer and by intermarrying—his wife, Bess, was Catholic. Houdini lived a mostly secular life. He was as likely to express his own brand of anti-Semitism as he was to brag about his Jewishness. But he did write about anti-Semitism in Europe and in Russia, which he visited while a pogrom was decimating the town of Kishinev.

And yet, once Houdini traded the stage for the pulpit, anti-Semitism rose up to haunt him and to urge him on. It was as if once he stopped playing at his stage escapes, he could no longer be tolerated. He intuited that many Spiritualists belonged to an elite WASP class from which he would always be excluded. In 1922, Arthur Conan Doyle invited his old friend to a séance hosted by his second wife, who supposedly made contact with Houdini’s beloved late mother, Cecilia. While communicating with Cecilia, Lady Doyle drew a cross; then, she transcribed an emotional letter to Houdini. Instead of convincing Houdini, the séance outraged him. He would later point out in public the unlikeliness of his mother, a Jew and a rabbi’s wife, drawing a cross—or communicating in English since she never spoke it in real life. Conan Doyle explained that his wife drew a cross whenever she channeled any spirit and that in the beyond, “Hebrew” was translated into English. The fact that Houdini’s mother spoke not Hebrew but German ended the men’s friendship.

The more ferociously Houdini pursued the Spiritualists, the uglier the anti-Semitic jibes became. Doyle called Houdini “our Disraeli.” When Houdini testified in front of Congress to promote a bill requiring fortune tellers to have licenses, one Spiritualist referred to him as Judas.

Not content with just tracing Houdini’s fascinating biography, the Jewish Museum exhibit also links the “mystifier,” as he liked to call himself, to 20th-century writers and artists. The most famous fictional Houdini, that of E.L. Doctorow in Ragtime, captures best the beleaguered escape artist ignored by the very American aristocracy that pays him money for his dog-and-pony show. But many of the post-modern artists represented in the exhibit catalog are less interested in Houdini’s Jewishness than in amplifying the escape artist’s particular historical meaning into a universal metaphor for S & M-style bondage: Typical is a still from Matthew Barney’s film, Cremaster 5, showing the naked artist manacled by plastic handcuffs to a stump in the snowy woods, a large mushroom sprouting from his thigh.

None of this work is anywhere near as enticing as Houdini himself. Captured in the 1920 gelatin print on the front flyleaf of the catalog and made visible on the front cover through a keyhole, Houdini gazes directly at the camera. Several strands of white hair frame his face, which is feline. His pupils are dilated, and his eyes are hooded with kohl. Houdini looks not unlike Al Jolson, another iconic Jewish performer in flight, another showy enigmatic son of a rabbi and mother-lover. Houdini died a year before Jolson starred in The Jazz Singer. Perhaps he had to die for Jolson to sing.

Rachel Shteir, a professor at the Theatre School of DePaul University, is the author of Striptease: the Untold History of the Girlie Show and Gypsy: the Art of the Tease.

Rachel Shteir, a professor at the Theatre School of DePaul University, is the author of three books, including, most recently, The Steal: A Cultural History of Shoplifting. She is working on a biography of Betty Friedan for Yale Jewish Lives.