Exegesis

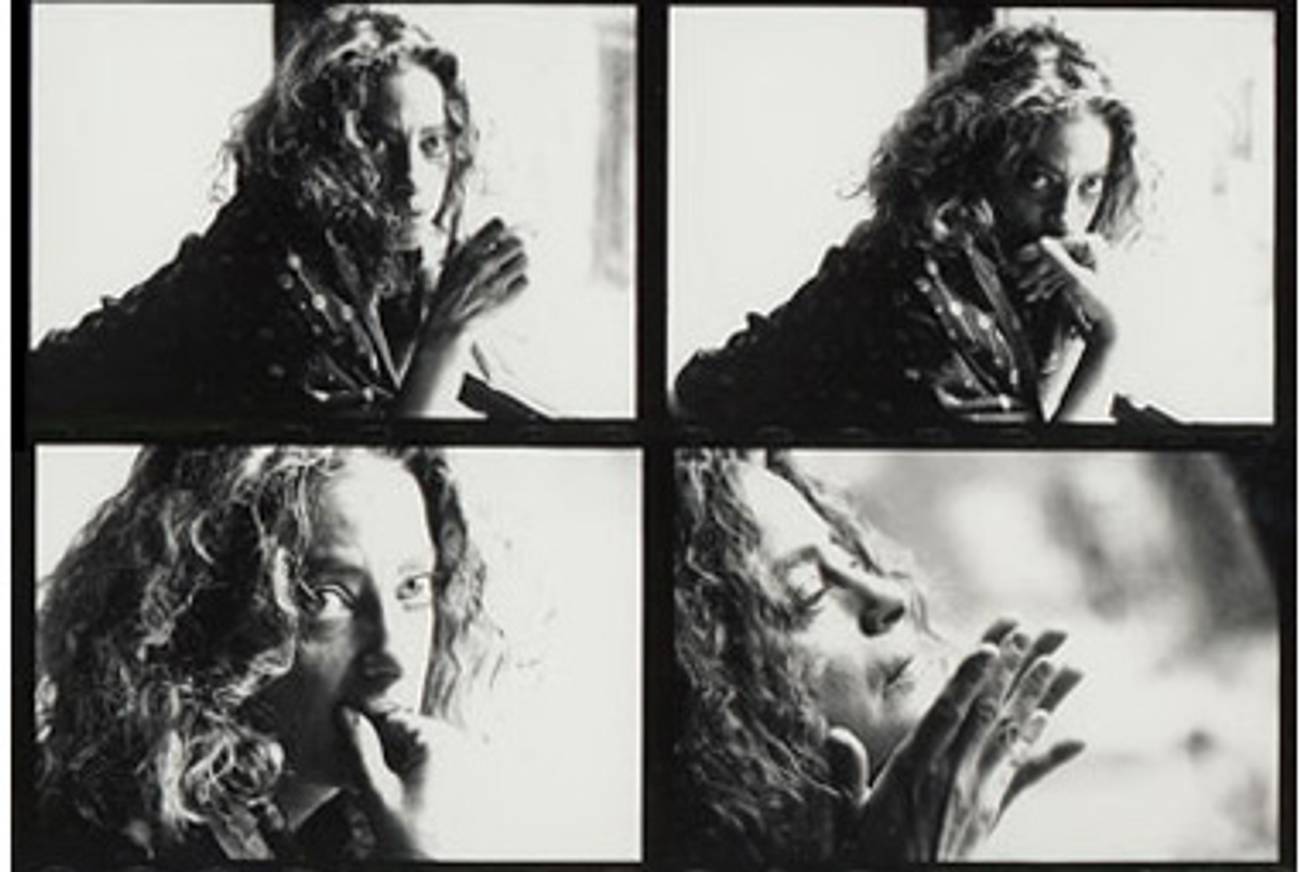

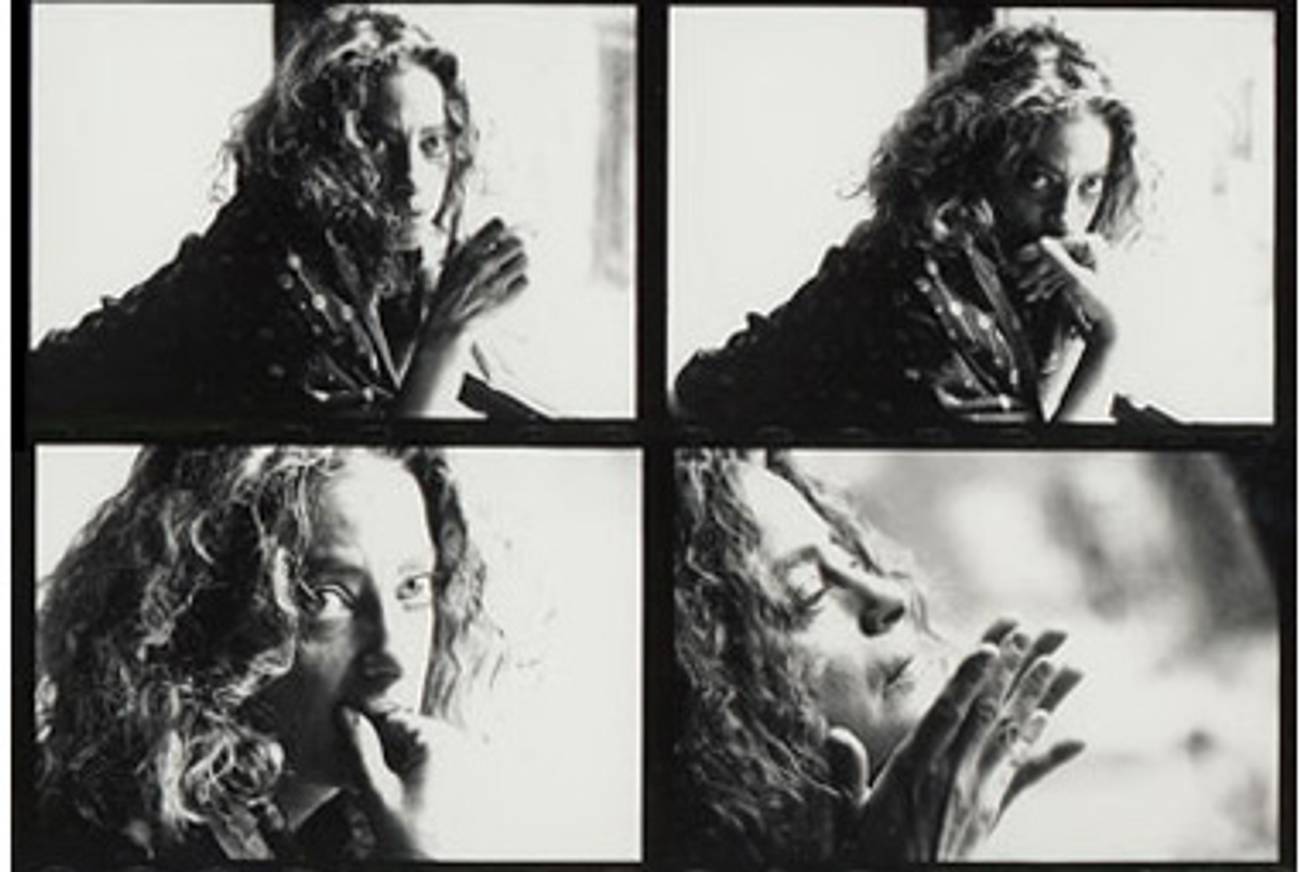

Jeanette Ingberman—the co-founder of New York’s Exit Art gallery, who died last week—brought a Talmudic sensibility to avant-garde art

Here’s a very partial list of things I have seen during a decade of frequently visiting Exit Art, a celebrated nonprofit gallery of alternative art in New York: a conical tower made of dirty, empty water bottles; a screen that displayed cryptic messages, such as “sex is chauvinistic” and “war makes freedom happen”; graffiti drawn with lipstick; 21 eggs in a pile, each painted to look like a skull; a woman tied to a column and inviting audience members to whisper secrets in her ear; and a man sweeping a sand-covered floor, daring viewers to kick at his neatly ordered dirt piles so that he may begin sweeping again.

For the most part, I would leave Exit Art’s stark, hollow exhibition space with the same cry on my lips that unites so many uninformed visitors of contemporary galleries: This is art? Even I can do that. I was often outraged, but I was never bored. And I returned, year after year, strangely drawn to the highly conceptual spectacles on display. I didn’t understand much about the art at Exit Art, but I was strangely drawn to it.

When I read Jeanette Ingberman’s obituary this weekend, my fascination became a bit clearer. The co-founder of Exit Art—together with her partner, the artist Papo Colo—died of leukemia at 59 last week. The obituary in the New York Times touched on all the expected milestones: doyenne of the avant-garde, champion of artists, believer in socially and politically conscious art. But the most curious revelation came somewhere toward the bottom, along with other dutiful bits of biography: Ingberman, the obituary said, attended Yeshiva of Flatbush, the renowned modern Orthodox day school in Brooklyn.

Suddenly, all those spirited, odd installations made perfect sense. They were conceived by a woman trained in forms, or, more accurately, trained to wander down all possible avenues of one particular form, the Talmud. While Judaism’s prohibition on idols might have made for a poor aesthetic tradition, its proclivity toward concepts, toward translating grand and ethereal notions into daily practices, made it stellar training for anyone interested in the heady world of idea-driven modern art.

In this light, I revised my view of the installations I had seen at Exit Art. Taken at face value, the works still seemed banal. The painted eggs, for example, represented fragility; piled up, they were meant to evoke the aftermath of a massacre. And the sweeping man was Sisyphus with a broom, here to remind us of the repetitiveness and the futility of our existence. For both works, and many more like them, the meaning is immediately clear, the experience not particularly interesting. But when you see the same works through a different lens, sharper and more Talmudic, a hidden layer appears. Suddenly, the sweeping man is inviting you to meditate not only on the futility of life but also on the futility of the acts of creating art and, perhaps, of consuming it. All art, after all, is transient: Even a great painting exists for us, godlike, only during the rare and brief moments in which we interact with it. When we leave the museum and go home, we’re left with a memory, an idea. Art is terribly ephemeral that way, and to understand it, to enjoy it, we build systems of looking and recalling.

The art Ingberman promoted challenged those systems repeatedly. In a 2000 interview with the Times, she explained her philosophy bluntly. “We’re constantly asking ourselves: ‘What is an exhibition, anyway?’ ” She knew, of course, that there was no answer. A yeshiva graduate, she was no stranger to the thankless and endless and intoxicating task of dedicating one’s life to interpreting something that is by definition fleeting and ultimately unknowable. But she never stopped trying, and it’s why I, and so many others, kept coming back even if the immediate reaction was bafflement or dislike; we, too, understood that our mission as spectators was to follow Ingberman’s lead and wonder with her, wonder about what art is and how we are to make sense of it in our own lives. Ingberman is gone, but her work, like that of the best Talmudic scholars, lives on, inviting us to argue.

Liel Leibovitz is a senior writer for Tablet Magazine and a host of the Unorthodox podcast.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.