What’s the Point of Passover?

Do today’s Seders exist to remember the past, or did past events occur so that they could be remembered later?

Jews gather at Passover Seders to recall their foundational story with gratitude and awe: God extracted an oppressed people from under the yoke of their oppressors, making of them a vibrant nation. The Seder of today acts out the drama of the past in order to keep the memory fresh. But at the same time, the tradition hints at a powerful alternate understanding of the Seder: God took the Israelites out of Egypt so that they would tell the story later. In other words, the events of the past took place so that they could be recounted in the future.

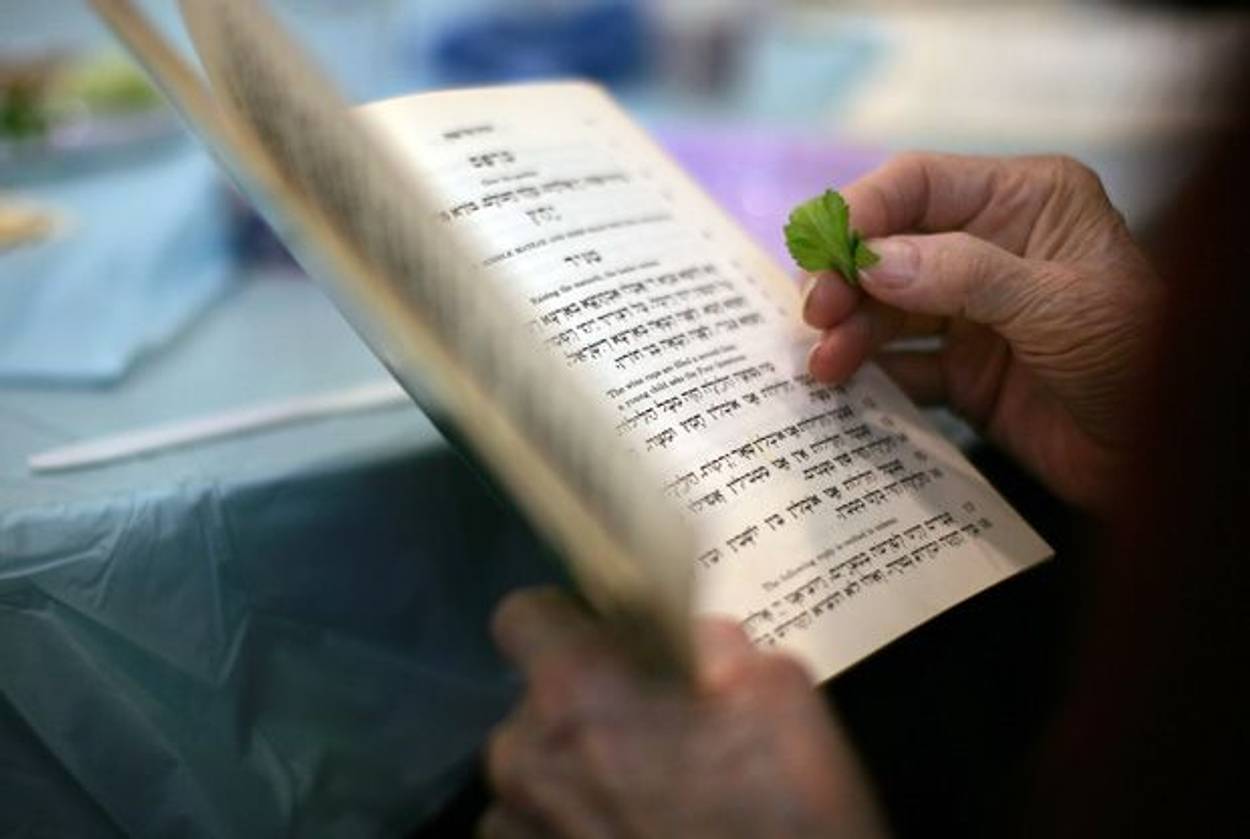

As the Passover Haggadah weaves its way through biblical and rabbinic texts, one verse from the Bible is quoted four times: Exodus 13:8. The verse instructs parents to teach their children about Passover. It is the kind of verse that the ancient rabbis adored; it can be read in two ways, one a straightforward reading that makes sense in context and the other an ultra-literal reading that reveals another perspective. The “sensible” contextual reading agrees with most translations of the Bible, as well as many English-language Haggadahs: “You shall tell your child on that day, ‘[I do it] on account of what the Lord did for me when I went out from Egypt.’ ”

Though it may very well capture the original intent of the passage, that translation is not really true to the slightly awkward grammar of the Hebrew. Literally, the verse says this: “You shall tell your child on that day, ‘On account of this, the Lord acted for me when I went out from Egypt.’ ”

Rashi reads it the second way. He asks, “On account of what?” What “this” is referred to here? For what purpose did God take the Israelites out from Egypt? Rashi concludes that the word “this” refers to commandments such as eating matzo and bitter herbs, which we now observe at the Passover Seder. He might gloss the verse like this: It was on account of future Seders that God acted in the past on behalf of the Israelites, liberating them from Egyptian bondage.

In two of the four places that the Haggadah quotes this verse—both of them in the passage about the four sons—it clearly means for Exodus 13:8 to be read in the first way. The wicked child and the simple child need to be told why the grown-ups are making such a big deal of the Seder. The answer, with a different emphasis for each child, is that “I do this (now) on account of what God did for me (in the past).”

In the other two places, the Haggadah makes more sense if you read the verse Rashi’s way. First, just after the passage about the four sons, the Haggadah expands the phrase “on account of this” into “on account of matzo and bitter herbs,” that is, on account of the Seder. Then, in the section after “Dayenu” when we are explaining the meaning of the Seder symbols, Exodus 13:8 is brought in to support the idea that “in every generation a person is obligated see himself as though he personally had come out of Egypt.” In other words, “the Lord acted for me” in Egypt—that is, so that I, thousands of years later, would tell the story and experience the moment of stepping from slavery into freedom.

In some contexts the Haggadah sensibly assumes that the Seder commemorates the Exodus. In other contexts it hints at the opposite: The purpose of the Exodus was that the Israelites would later perform the Passover rituals—that they would one day become tellers of the Passover story.

In the Bible, the prototype Seder is organized around creating memories. It happens while the Israelites are still slaves. The ninth plague has ended, darkness has lifted over Egypt, Pharaoh has been warned about the killing of the firstborn, and everybody is in waiting mode. God tells Moses to instruct the Israelites to make a special meal, giving them 10 days to plan and four more to prepare:

Speak to the whole community of Israel and say that on the 10th of this month each of them shall take a lamb to a family, a lamb to a household. But if the household is too small for a lamb, let him share one with a neighbor who dwells nearby, in proportion to the number of persons: You shall contribute for the lamb according to what each household will eat. Your lamb shall be without blemish, a yearling male. You may take it from the sheep or from the goats. You shall keep watch over it until the fourteenth day of this month. Then the entire assembly of the congregation of Israel shall slaughter it at twilight. (Exodus 12:3-6)

A great deal of discussion will be required to organize the whole neighborhood into lamb-sized pods, taking into account appetites and preferences. Then the selected lambs must be guarded so they don’t sustain any injuries that might make them unkosher. So far, it sounds like the weeks before Thanksgiving: Invitations are flying, matches are being made for the lonely, and turkeys are being ordered. Then, a few days before the holiday, all the turkeys come out of the freezer to defrost at just the right speed—they mustn’t spoil, but they have to be ready for Thursday morning.

But there the similarity ends: On Thanksgiving, everybody will dress in their finery and sit down for a leisurely meal. At the first Seder, the instructions specifically call for a meal on the run:

They shall eat the flesh that same night; they shall eat it roasted over the fire, with unleavened bread and with bitter herbs. Do not eat any of it raw, or cooked in any way with water, but roasted— head, legs, and entrails—over the fire. (Exodus 12:8-9)

This is a recipe for street food: Take some flat bread—maybe a laffa—and smear it with spicy sauce. Grab some meat off the grill and wrap the whole thing up. This is a meal that can be eaten with one hand. There are to be no leftovers, no Tupperware containers to distribute, and the dress code is very specific:

You shall not leave any of it over until morning. If any of it is left until morning, you shall burn it. This is how you shall eat it: your loins girded, your sandals on your feet, and your staff in your hand. And you shall eat it in haste. It is a Passover offering to the Lord. (Exodus 12:10-11)

In biblical language, girded loins, sandals, and staff in hand signify traveling clothes. After 15 days of careful preparation, everything about this meal makes it sound like wolfing down a sandwich while waiting for the bus. It is this ritually hurried meal that will be the model for the long, slow Seders of the future.

The Israelites at the first Seder are in a state of instability. They stand on the threshold between slavery and freedom, with one thin doorway separating them from the death swirling around outside. They are commanded to intensify their unstable condition by acting it out with a ritual meal. Leaving Egypt, all the members of the community will have the same taste in their mouths, a powerful taste that will forever recall this moment. This will be the taste of the departure from Egypt.

In this story, the idea of remembering comes before the thing remembered. Before they slaughter and cook their lamb, before they eat the meal, before they escape from slavery, the Israelites are told three times that they are supposed to be creating memories. Exodus 13:8 is one example. Here is another:

When you enter the land that the Lord will give you as he has said, you shall observe this ritual. When your children say to you, “What is this service to you?” you shall say, “It is the Passover sacrifice to the Lord because he passed over the houses of the Israelites in Egypt when he smote the Egyptians, but saved our houses. (Exodus 12:25-27)

At the first taste of their traveling meal, the Israelites already know that year after year they are to put that same taste in their mouths, awakening the visceral memory of being about to leave Egypt, about to be free. They are to pass that taste down, along with the story, so that the memory is as real for the children as for the parents. Every generation will taste what it means to be poised on the brink of freedom.

The Haggadah is the product of the mishnaic period, after the fall of the Temple, when the rabbis were working out how to be Jewish without the sacrificial rites. Thus, it leaves out the main course of the original Seder meal: the paschal lamb. Instead, the Haggadah evokes the road from slavery to freedom with expansive words and with the evocative flavors of symbolic foods. Near the beginning of the telling it says:

Now we are slaves, next year may we be free.

A few lines later, it says:

We were slaves to Pharaoh in Egypt, but the Lord our God took us out from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm.

Which is it? Are we slaves on our way to freedom, or are we free people who were once slaves? At the Seder we taste both slavery and freedom. Through what goes into our mouths and what comes out of our mouths, we learn and re-learn every year that we are travelers out of Egypt. We are neither enslaved nor free. We occupy a world that is poised between slavery and redemption, and our challenge is to live a life infused with both realities.

The tool we have to meet this challenge is the story. It changes us by bringing a collective past into living memory, teaching us gratitude for redemption. From another angle, the value of the past is that it gets the story started. It is only by living inside this story that we can become people on the road to redemption.

Rabbi Helen Plotkin teaches at Swarthmore College and at Mekom Torah, a Philadelphia-area Jewish community learning project. She edited and annotated In This Hour, a collection of early writings by Abraham Joshua Heschel.