The Brooklyn building where I live is populated mostly by big Yemeni Muslim families; on special occasions, celebratory ululating travels up the air shaft, and often you can hear the teenagers arguing with their parents in Arabic. But now and then I hear the chanting of prayers in Hebrew. When I moved in, my boyfriend, Jonathan, pointed out a couple that lived downstairs in an unusual arrangement: They have two apartments, one on top of the other, so you often see them heading up or downstairs. One of their apartments was the source of the Hebrew prayers.

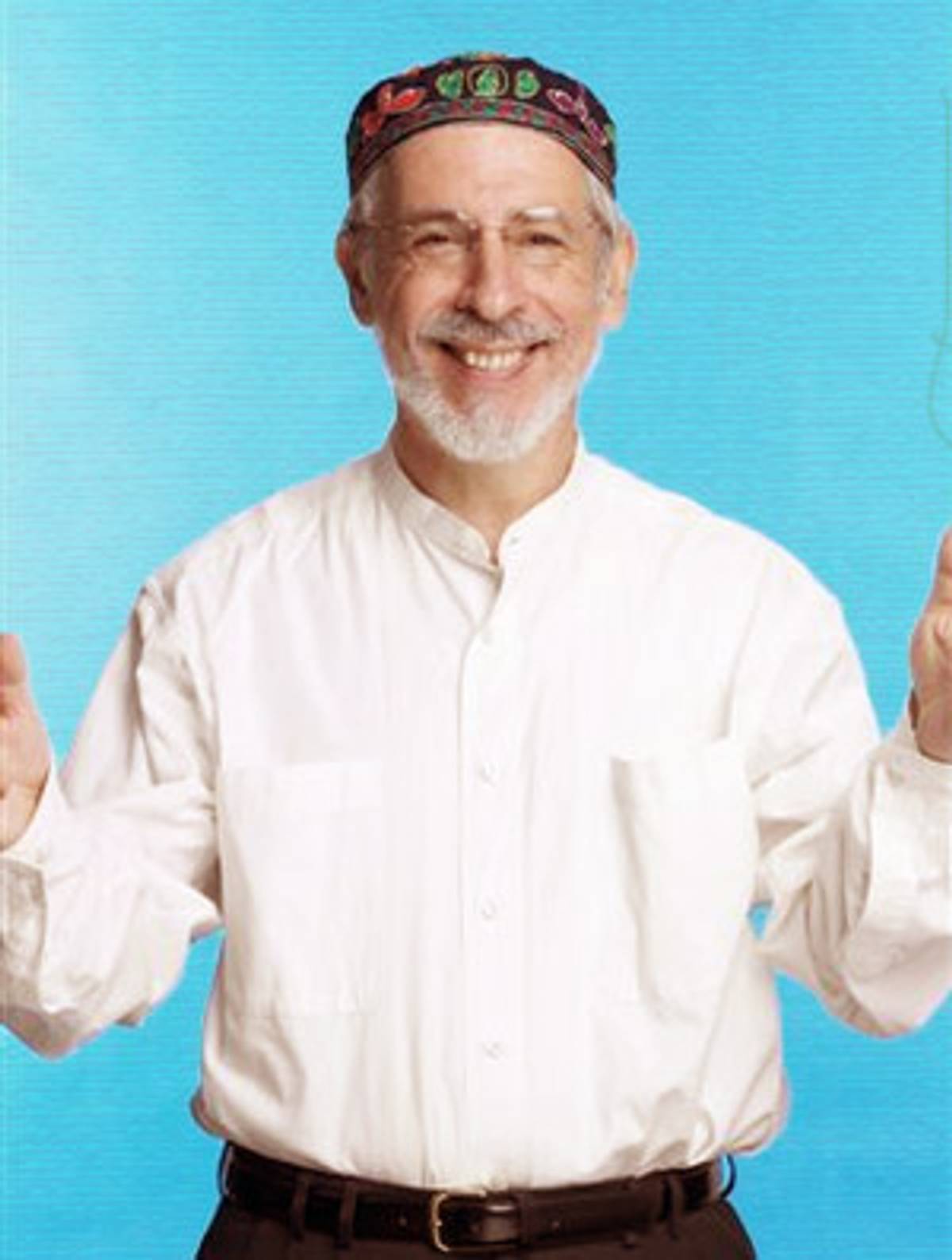

As happens in walk-ups, one day I passed the woman—petite, beautiful, black-haired—on the stairs four times. We finally introduced ourselves; Carole warmly welcomed me to the building. I met her husband shortly after that. Yitzhak Buxbaum is a small, wiry 63-year-old with a close-cropped beard. He usually wears a beret and jogging shoes, and has an odd air about him—at once intense and distracted. In our hallway chats, I learned that he had written several books about Judaism and spirituality (among them The Life and Teachings of Hillel, A Person Is Like a Tree, and The Light and Fire of the Baal Shem Tov), and that he has a commercial website—jewishspirit.com—that bills itself as a “gateway to spirituality, mysticism, and kabbalah.” Most interesting to me was the fact that he was a maggid, an ordained storyteller. I’d never met one before, and I was curious about how and why he came to be one. Luckily, Yitzhak loves to talk.

We met in the second-floor apartment, which is full of books and decorated with exquisite religious paintings—Hindu, Buddhist, and Christian as well as Jewish. This is where Yitzhak does his teaching and writing, and Carole gives yoga lessons.

On your website, you mention in passing that you used to be an atheist. That surprised me.

When I went away to college, that was the first time I was required to put religion on a form, and I put “none,” because like many people of my generation—maybe yours, too—after the bar mitzvah that was the end of it. I happily call myself at that period a fastidious atheist: philosophically hardcore and strict. My mother was an atheist. My father believed in God, but not in a very active way.

I was studying biology and zoology—that was my field of science. There is an inclination in science, of course, to be materialistic: not in a greedy sense, but in terms of spirituality, needing proof. I didn’t have any belief in a big person in the sky. That was my scientific attitude, coming through my rationalism.

But as far as I can tell, your life now is devoted to the religious and mystical. Something clearly changed. What happened, and when?

Because of the crisis of the Vietnam War I was depressed, like many people, and I had to decide what the meaning of life was. So I started to explore, just a little bit, religion, which was very strange for me. I was influenced by Tolstoy, who at the age of fifty became totally religious. His Confession is amazing. It’s a seventy-page book that explains how he came to believe in God. And I read Kierkegaard; his idea of the leap of faith was also influential for me. I had to figure out how one departs from rationalism.

I had been going to graduate school at the University of Michigan. Then, because of the war, and the turmoil connected to it, science seemed irrelevant. And my interest in animals seemed irrelevant. I learned about rich and poor, and the suffering in the world, and oppression. I dropped out. I was in my early twenties. I was this wild radical, with what I called a Hebro, the Hebrew version of the Afro.

If you weren’t a student, it was a matter of going to the Army, going to jail, going to Canada, or teaching. I followed a friend, a Harvard guy, back to Cambridge and I started teaching high school, but it meant nothing to me. I had to discover the meaning of life, or else I was going to lose myself. I spent weeks and months thinking. I’d sit in the Pamplona Café for hours. People thought I was doing nothing, but I was the most intensely focused I had ever been in my life.

Then one night I was walking down the street, and I realized that the deepest thing I knew was that I had to do good. If I felt obligated to do good, what was obligating me? It was not from my parents, it was not from the culture; it was something very, very deep. Half a year later I realized it was God.

Was your search for the meaning of life always tied up with Judaism?

At about the same time that I had that realization, I was also thinking about being Jewish, which had previously seemed of no interest or relevance. I reflected on my Jewishness along the lines of the “black is beautiful” and women’s movements, and recognized that I was ashamed of who I was due to an internalized anti-Semitism. I opened up to investigate Judaism. I read Martin Buber, and then went to see Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, my great rabbi.

The first time, I went with a friend to Brandeis, where Shlomo was appearing in the student union building. He spoke and sang so beautifully. Forty-five minutes into the event he jumped up, and all the people around us jumped up—and started to jump up and down to the music. I said to my friend, “Let’s get out of here. This is a worship service!” I wasn’t ready for worship. I was dipping my toe in, and someone shoved me in the pool—but I didn’t know how to swim. But after some months I was so attracted by the perfume of Shlomo’s holy presence that I just had to see more of him.

I started going to the Hillel at Boston University regularly. Shlomo was teaching there. After some time of attending, I came up with the correct question for him. I realized that God is not an object, so we can’t ask, “Does God exist?” the way we ask, “Does a table exist? Does the building exist?” A person from a rationalist perspective thinks they can just cogitate, “Is there a big person in the sky?” God is something different. So at a question-and-answer session, I said, “Shlomo, I’ve never met God.” And Shlomo said, “Brother, I would like to introduce you.”

What happened next?

Well, I left Cambridge, came to Brooklyn, and went to Lubavitch yeshiva. I studied with them for half a year. I grew payes and a beard. I always have to be a radical.

What did your mother and father think of all of this?

My mother was a very tolerant, nonjudgmental person. She wondered why I did this, but she was okay with anything that I did. My father was thrilled, because he had been trying to tell me for years and years and years how Judaism is the meaning of life. He was a businessman, and he hadn’t been very articulate, but he was sincere. But he couldn’t bear the fact that I had long payes, these sidelocks. I learned in Lubavitch that you can make a deal—a business deal—about religious things, which, from a secular point of view, seems totally bizarre. I said, “Dad, if you’ll put on tefillin, I’ll cut the payes.” So he put on tefillin every morning and I cut the payes. And it had an amazing effect, because he came back to religion.

Well, from the beginning, it was the center of my life. Once I decided what the meaning of life is, I didn’t go back to a relaxed attitude. In fact, Abraham Joshua Heschel, the famous rabbi, said, “If God is not the most important thing, He is nothing.”

When you decided to make God the center of your life, did you go through any emotional or psychological changes?

In one sense your personality changes. In another sense, it doesn’t; I am the very same person I was when I was an atheist. One thing that happened was I ceased being interested in music other than religious music. I am not proud of it, or think this is the correct way to be. I just lost an interest in secular music, because music speaks emotionally—and emotionally I am tuning into God all the time.

How did you figure out how to combine your religious life with a way to exist in the material world? You didn’t want to be in academia anymore, you weren’t a businessman like your father.

Martin Buber’s Tales of the Hasidism showed me the kind of lifestyle that I admired: people who were tremendously devout and religious, but had friends and family. So as I started to read more and more the Jewish stories, I started a little group. I would read a story and we would discuss it. And that evolved into my becoming a maggid, meaning an inspirational speaker and storyteller. I received s’micha, the ordination to be a maggid, from Shlomo.

And then I started writing books. I was constantly reading all these texts that presented high ideals, religiously and spiritually, in Judaism. I said, “Yeah, I’d like to do that.” But I didn’t know how. So when I encountered nitty-gritty, practical ways to attain something spiritually I would note them down. And then I realized, “Gee, this stuff is not available.” And that’s when I produced my first book, my gigantic book, Jewish Spiritual Practices.

What happened after you published this gigantic book?

I became a teacher of Judaism. I taught for many years at the New School. I taught Jewish mysticism, and also ecumenical courses, like “Spiritual Stories from Around the World.” I taught at Makor for a number of years. I have taught at, like, five hundred synagogues.

After I had been doing this for about twenty-five years I decided it was time to train other people. I started a program to train people to be maggids. Twice a year people come for an intensive. I have ordained ten people already over the last two years.

How do you decide whether they are ready to be ordained?

I am not trying to put impediments in people’s way if someone wants to spread God’s light. If they go through it with some attention I generally give s’micha. My wife, Carole, went through the program, and she had no aspirations to become a maggid. But I gave her ordination as a baal misapair ruchani, a master spiritual storyteller.

If God is the center of your life at every moment, how do you also have a marriage?

One of the things about Judaism is that it is nothing crazy, you know? Camus said that he didn’t want to be more godly, he wanted to be more human. And I think that’s the Jewish attitude. Carole is religious, but not as “fanatical” as me. I think it has become more central to her, but my secular interests are limited. It sounds bad, but it isn’t, I hope. She’s a big outdoors person. She has more interest in the world and seeing things. I go along and have a great time, but I am less motivated. It’s like Rabi’a, this great Muslim mystic in the early days. Her assistant told her to come outside and see the wonders of God, and Rabi’a told her to come in and see God Himself.

Why do you feel it’s your job to teach people about God and Judaism and mysticism?

You know that Muslim group called Tablighi Jamaat? They are worldwide, but they are more based in Pakistan. They are proselytizers, and the Western intelligence services feel they are providing a pool for the Jihadists. But ten or twenty men go out to another country or a remote area of their own country, and proselytize for a month. The Mormons do something similar. And Lubavitch has it built in, too. But I feel that the other branches of Judaism have to come up with some radical way to institutionalize proselytizing among the Jews. Nobody is ashamed to stand out on Court Street and pass out literature about environmentalism or politics. So why should people be ashamed to pass out spiritual literature?

The idea of proselytizing rubs many people the wrong way.

I feel that the Jews have to get over this. So many of our people are unconnected religiously.

Have you had any doubts since all this started? Any dark or confused days?

I don’t have any doubts. For my intellectual integrity, I have to allow that there is, like, a one percent chance there is no God. But I don’t operate that way. And if there wasn’t a God, it would be some kind of glorious mistake, just about the noblest mistake possible. I am not a seeker; I am a finder. People too much glorify this questioning in Judaism.