Not a Chef, Not a Restaurateur, but an Expert on Jewish Culinary Literature

Meet Janice Bluestein Longone, the woman behind one of the most important collections of American culinary ephemera

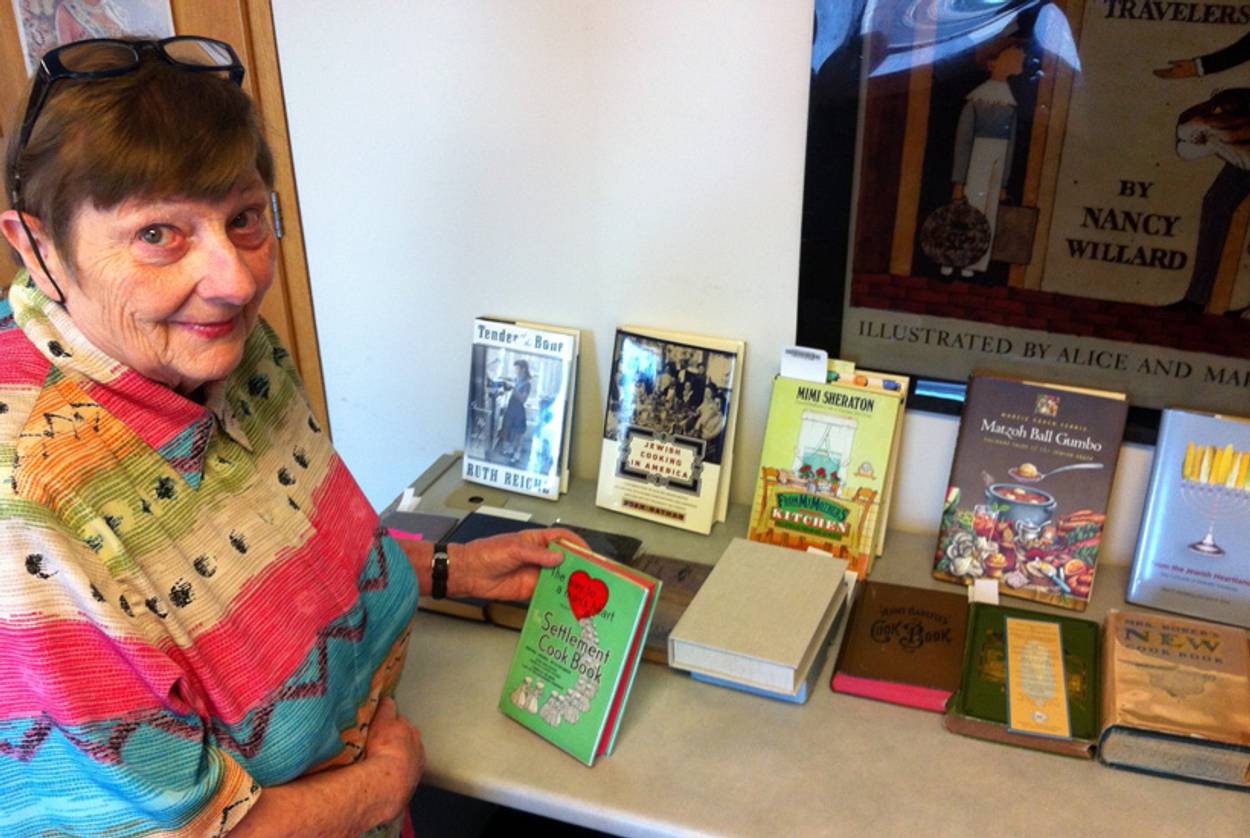

Janice Bluestein Longone cradles the slim, slightly tattered gray volume gingerly in her hands, endeared by its brittle, imperfect pages with water-damaged corners. The 1903 book probably raised only a few hundred dollars to help furnish the recently built Temple Beth El in Detroit, but its value to her is, at least in this moment, incalculable.

The Temple Cook Book is not the most important piece she is prepping for the three-month exhibition of Jewish gastronomic literature that kicks off Sept. 4 at the University of Michigan’s Hatcher Graduate Library in Ann Arbor. Of the nearly 200 items to be shown, the centerpiece is undoubtedly an exceedingly rare copy of the first known Jewish cookbook published in America: Jewish Cookery Book, written in 1871 by the mysterious Mrs. Esther Levy. The school acquired it at auction in 1996 for $13,000.

But at this moment, the 80-year-old Longone is mischievously gleeful about how she guilted the folks at Temple Beth El, now located in Birmingham, Mich., into forking over a now-precious artifact that likely was hardly regarded with much significance in its own day. “I called them up, and I told them we have the first Jewish charity cookbooks from Oregon, Washington, California, and from other states, and I don’t have the first one from our own area, from Detroit? We need to have this for this exhibition, you know what I mean?” Longone recalled, her trembling voice rising and falling for emphasis. “Finally, I wore her down. The woman said, ‘OK, I’ll get the box.’ Box? They had this box of old documents! She came back and said, ‘We have a copy but I can’t give it to you, we have to ask the committee, I have to ask the rabbi, I’m going out of town for two weeks.’ And I said, ‘But we need it now.’ And we got it.”

For more than four decades, this has been Longone’s route to amassing one of the most acclaimed and important collections of American culinary literature and ephemera. Yard sale by yard sale, auction by auction, persistent cold call by persistent cold call, she’s created a 25,000-item assemblage now largely in the possession of the university’s special collections that is so significant that former Gourmet editor Ruth Reichl, the late New York Times food guru Craig Claiborne, and countless others have flocked to Ann Arbor for research.

Longone is an unlikely star of the culinary world—she’s never owned or operated a restaurant, never been paid to cook except as part of class demonstrations—but an undeniable one nonetheless. No less than James Beard, in fact, once credited her with having “codified American culinary history and created a benchmark.” In 2011, she received the Amelia Award honoring lifetime achievement in culinary literature from the New York Public Library and the Culinary Historians of New York. The award is named for Amelia Simmons, author in 1796 of the first known cookbook printed in America, which, Longone notes, is where the pairing of turkey and cranberry sauce was introduced. (The university, of course, has a first-edition copy.)

Raised in a secular Jewish home in Boston, Longone began her fascination with cooking when she and her husband were in graduate school at Cornell in the 1950s and frequently hosted foreign students for dinner. To understand the various cuisines, she sought books and became enchanted by what they told her about how people lived in other countries and what they ate.

Yet it was the students’ assignments to her—to make them “typical American meals”—that alerted her to how vague and circumstantial that term is. “I started looking for and finding and then collecting books, and unbeknownst to me I must have decided I was going to open an antiquarian cookbook shop because I had been buying every book I could find in rare book shops but I’d buy four copies,” she said. “I must have known I was going to sell them or try to sell them.”

Indeed, in 1971, by then ensconced in life as the wife of a University of Michigan chemistry professor, Longone debuted her mail-order antiquarian bookshop out of her basement, where it remains today. In the beginning her only advertisement was a couple of lines in the New York Times book review section, but within weeks the likes of Claiborne, Alice Waters, and Julia Child were calling her for intel. Ari Weinzweig, owner of Ann Arbor’s famed Zingerman’s Deli, developed one of his restaurant’s distinctive table breads, derived from an 18th-century recipe of rye, corn, and wheat, from resources in Longone’s “deeply helpful” collection.

The bulk of her collection moved to the university in the 1990s and later became the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive. From there, doctoral candidates have relied on it for research on everything from the importance of corn in American culture to the history of military food to the role of ice and refrigeration. Documents in the library change the understanding of what is traditional food in many cultures and help pinpoint the introduction to American society of such items as the kebab, the bagel, and the tuna casserole. Recent acquisitions include letters and published works by Sarah Tyson Rorer, a late-19th-century pioneer of “dietetics”; an advertisement tied to the 1892 World’s Fair in Chicago; and an 1888 book on temperance that has a large fold-out map of Manhattan showing the location of every saloon.

This fall’s exhibition of Jewish material from Longone’s collection emerged from the prodding of Judaic-studies master’s student Avery Robinson, whose thesis focuses on the largely untold history of the lowly kugel. The Jewish focus is near and dear to Longone, of course, because of her own heritage, but in many ways the displays reflect many standard themes of the broader field of study.

In particular, the heart of it will be charity cookbooks from synagogues and Jewish groups in all 50 states, a feat that Roberta Saltzman, the NYPL’s Jewish-collection curator, regards as “a significant achievement” because “charity cookbooks are almost by definition ephemeral. They are published, after all, to raise money for a specific cause. Very few charity cookbooks stay in print for many years.” Longone has long been especially intrigued by charity cookbooks, which began popping up in the 1860s and for decades were a critical means for women to collaborate, raise money, and record their cultural and familial food histories. The Longone collection is not the largest or most important of the nation’s Jewish culinary collections—those of the NYPL, Harvard, and Hebrew Union College lead that list—but its emphasis on charity cookbooks does make it stand out, Saltzman said.

The Jewish charity books reflect geography, religiosity, and the level of desired or perceived assimilation. Books from places like Nebraska, for example, avoid references to Judaism or synagogues with titles like Our Sisters’ Recipes and by dubbing what are obviously kugels as “Easter pudding.” Older ones offer recipes for dishes that are far from kosher—“they took more as far as I can see to the shellfish than pork, but eventually they had pork and they had ham and other things,” Longone said of colonies of German Jews in places like Seattle—while more recent cookbooks from even Reform groups show an increased interest in kosher foods.

Robinson’s own research exemplifies the history and context provided by these texts and what they say about how people ate, where they were from and what, from one moment to another and one region to another, they felt about their Jewishness. Consider, for instance, the implications of something as seemingly minor as whether a kugel recipe has raisins in it as indicative of which side of Europe’s so-called “Gefilte Line” a group of Jews might hail from.

“North and east of this line, which runs along eastern Poland and dumps down southeast into the Ukraine, you tended to eat savory foods,” Robinson said. “Your gefilte fish did not have sugar, and you would never put raisins or any more than a scant teaspoon of sugar in your kugel or other foods. If you lived west or south of this line, you would have sweet kugels, you would have lots of raisins.”

Beyond the exhibit’s charity cookbook collection, Longone and Robinson plan to show how Jewish foods affected the broader culture as well. In The Virginia Housewife, published in 1846, author Mary Randolph advises readers to seek out meats from kosher markets because she trusts “none but the Jewish butchers, who are paid exclusively” to know how to avoid the “flesh of diseased animals.”

Longone, who says she’s put in more than 60,000 volunteer hours curating her collection for the library, is still formulating the lecture she is scheduled to give on Sept. 24 to officially kick off the exhibition. She is likely, she says, to explain that as much as she has learned about Jewish life in the United States from the books that she has, she remains vexed by the limited information available about the life of Jewish Cookery Book author Esther Levy. Part of her enthusiasm for her avocation has been a sense that she can reclaim the stories of and provide credit to female pioneers, and to that end she and her husband have traveled the nation trying to learn more about women like Levy, Simmons, and Malinda Russell, author of the 1866 pamphlet believed to be the first cookbook written by an African-American.

The quest, Longone says, continues and with it more revelations even for her. “What I’m learning through this exhibition is that many of the things that I could attribute to what I’m finding among the Jewish cookbooks are exactly the same thing as the Protestants were doing but early on,” she said. “I mean, it’s really very interesting.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Steve Friess is a former senior writer for Politico who lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Steve Friess is a former senior writer for Politico who lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan.