Learning Judaism as a Native Language Requires More Than Synagogue Once a Year

Becoming fluent in your own religious tradition is like playing an instrument or a sport: It takes time, dedication, and practice.

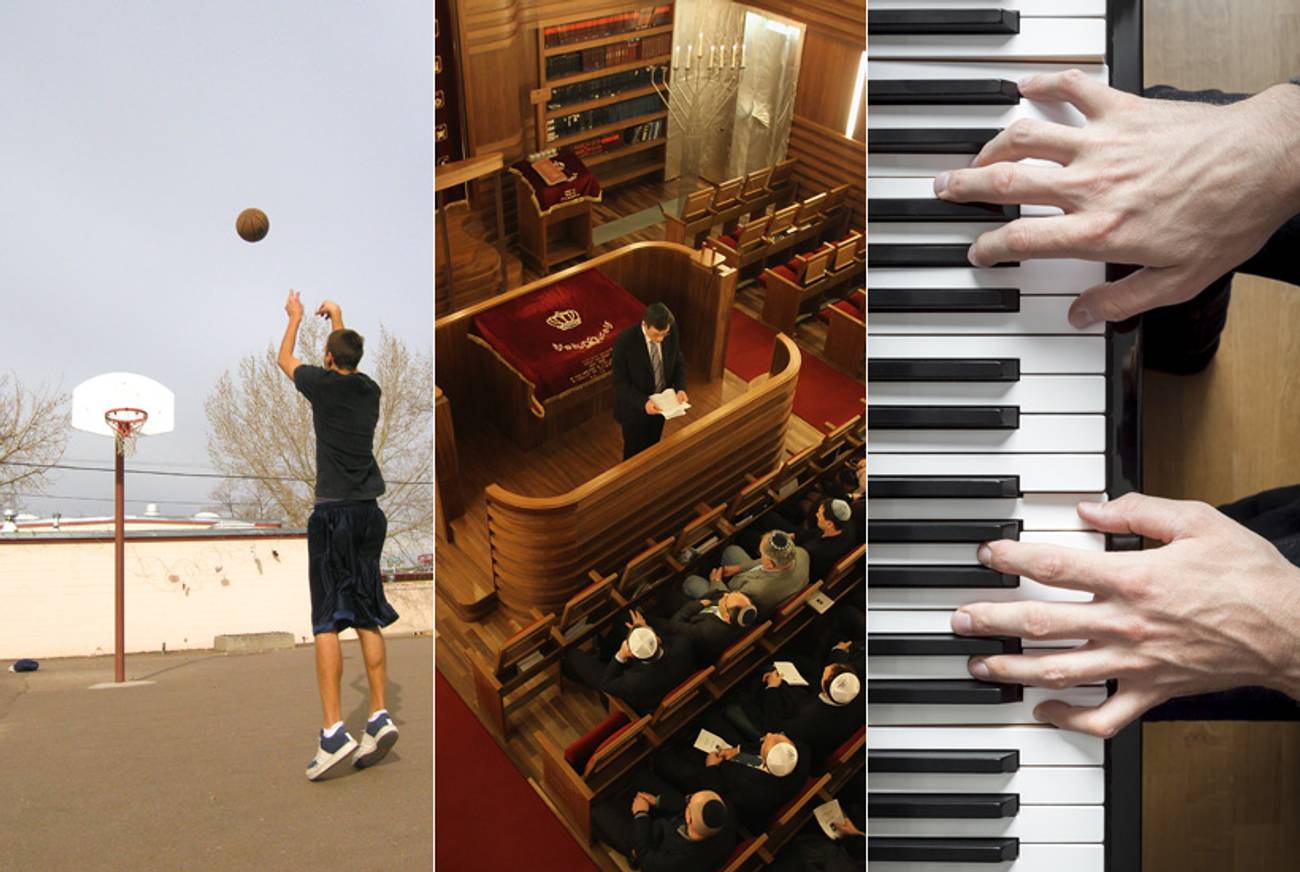

It’s the High Holiday season, the time of year when synagogues double or triple or quadruple in attendance, as barely affiliated Jews stream back through the sanctuary doors, looking for their yearly connection. Some are scared, others disdainful, many bored. And confused—lots of confusion. As someone who writes about religion for a living, I have conversations throughout the year with these “High Holiday Jews,” but also with other Jews, some of them regular worshippers, others infrequent, who are trying to figure out why Judaism is so hard for them. I’m not a rabbi and I don’t have any good answers, but I do have some reflections, which I hope will put some people’s minds at ease, maybe even help them.

The basic problem is that for many people, Judaism used to be a native language. For many of them, it was a second language—after Russian, or Polish, or English, or whatever. But it was still spoken in their home, in one way or another. What’s more, because Jews were forced together by anti-Semitism, laws, or mere custom, Jews knew plenty of other Jews. Often, they knew other Jews almost exclusively. So, even if one was not from a very learned family, one still felt that a Passover Seder, or even a Simchat Torah parade, was familiar, friendly, native. Your family might go to synagogue only a few times a year, but when you went you saw friends, neighbors, relatives. Even if you didn’t understand the prayers or connect with any of it spiritually, you still felt more or less at home.

That was Judaism as a native language.

These days, except for tiny Jewish minorities in gentile lands, or for the Orthodox who live among other Orthodox, Judaism is not native to anybody. Even many Israelis are now estranged from, and don’t understand, Jewish religious practice. So, for most of the Jewish world, Judaism the religion is now a learned practice. It can still give great joy and meaning to one’s life, but most of us can never practice Judaism in the easy, unearned way that, say, I can celebrate the rituals of being American: the Fourth of July, Thanksgiving, Super Bowl parties.

So, if Judaism is no longer a native language for many Jews, what is it? I believe that Judaism is best thought of now as an art, or maybe a sport. Put in even simpler terms, it’s like playing guitar, or playing tennis.

Consider that playing guitar is very, very hard when you start. Let’s say you take a beginner’s class. At the beginning, you will feel frustrated and embarrassed when you make mistakes. If you don’t even know how to read music, and if, what’s more, you lack a good ear, then you will be surrounded by people, even in that introductory class, who seem far ahead of you. You may go back for a few weeks in a row, and you may even practice every night, but after a month you won’t have made what seems like satisfactory progress. Meanwhile, if you bump into fellow students, or hang out at the music school, you will feel as if all of them are ahead of you, making more progress, and coalescing into a community of musicians that you will never be able to join. Some of them may start jamming together, or using lingo that you have yet to master. You will already be defeated. (This doesn’t have to be guitar, of course. It could be violin, cello, lute, whatever.)

And what if you only went to this music class once or twice a year? (You can see where I am going with this.)

But of course, to give up then would be absurd. You have only been at it a month. (Or, perhaps, only a couple times a year for the past 30 years.) The people who are even passably good have spent more hours immersed in it. Maybe they got their competency by spending 40 hours a week for a month or two—they crammed, intensively. Maybe they spent a few minutes a week, but for years on end. Whichever the case, they, too, were once clueless, but by spending time with the instrument, they began to get the hang of it.

And now, of course, playing their instrument no longer seems like work. It’s fun, it’s joyous, it’s spiritual, it connects them with a community of like-minded people; those people have kids and spouses who hang out together, they have annual rituals—jamborees, hootenannies, whatever. On occasion, when they want to learn a new style of playing, or work on a particularly difficult piece, they may get frustrated again—it will seem like work again. And of course some of the people in their musician clique are obnoxious or stupid or crass. It’s not a perfect community. But by and large their musical practice has moved from the realm of drudgery into the realm of joy.

So it is with some kinds of Jewish practice. The first few, or even few dozen, times you try it, it’s not just hard work—it seems as if you’ll never get it. The prayers are in a foreign language, you don’t know when to stand or sit, and it seems as if everyone else has known these things forever. (Obviously, some Jewish services are in English and can be quite user-friendly; but even then, the newcomer will have some of these feelings of inadequacy.) What’s more, it seems as if all the people around you are old friends with each other, and you are the newbie. But if you keep coming, it’s amazing is how quickly you begin to feel a sense of mastery. The fifth time you try it? The 10th? All of a sudden you are part of the community, you know people, you know when to stand and sit. And you are teaching some newbie who arrived after you.

I should say that I can’t play an instrument. But when I see my friends who can, or watch my daughter with her Suzuki violin lessons, I always think it’s a good analogy to religious practice. But let’s try another analogy: sports. Most sports, when you first play them, are humiliating. How many years of basketball do you need behind you before you dare to join a pickup game in the park? How many years of tennis lessons before you aren’t constantly spraying nearby courts with your errant balls? But again: Once you get good, you have a joyous activity for a lifetime.

These analogies in a sense will be very unnerving for many American Jews, for two reasons.

First, a lot of us don’t want to spend five or 10 Saturdays a year, let alone 52, in synagogue. Or three minutes a day with a prayer book. Or two intensive weeks in the summer. However you divvy up the time, it sounds like too much. If that’s what it takes to really feel comfortable with the tradition, then to heck with it. To that I can say: OK, no problem. I’m not here to save you. Do whatever you want. I wrote this essay to comfort you, to reassure you that it’s not you, and it’s not Judaism. You are fine, and the religion is fine. But the religion is not native to you anymore, so if you do want a greater ease with it, it will take some time. Just as with guitar, or basketball. Or French or Swahili. If they aren’t native, they take a little work.

Second, some Jews will be unnerved because they don’t want to be told that their Judaism is no longer native. They feel Jewish, after all. Maybe they like lox, or Woody Allen, or Jonathan Safran Foer, or Yiddish expressions, or Adam Sandler’s “Hanukkah Song.” If they feel such comfort with aspects of Jewish culture, why should they feel so alienated from synagogue attendance? And who am I to tell them they are non-native Jews? My only response is that if you got this far in the essay, it’s probably because you want some connection with the religious tradition, not just with the cultural tradition. You want the Jewish religion to nurture you somehow—maybe at weddings or funerals, maybe when your child is born, maybe when you have questions about how to spend your brief time on earth. And for that kind of stuff, Blue Jasmine won’t do the same work (although I hear it’s one of his best in years).

Religious practice, like musical or athletic practice, is easier for some than for others. For some people, it is so difficult that they probably should not even bother. I have no ear for music, and if I wanted to learn guitar even reasonably well it would take so many hours, at the cost of so much frustration, that I should probably just skip it. For some people, religion is like that: They don’t get it, they don’t see why it is meaningful, their not-getting-it makes them angry or resentful or sad or bored, and they would always rather be doing something else. Such people should, I think, stop trying. Don’t worry that your bubbe is looking down from heaven ashamed of you; after all, you don’t believe in heaven anyway. On Yom Kippur this year, do something that brings you joy, that takes you out of yourself, that helps you reflect, but don’t come to synagogue.

For everyone else, however, those of you who feel that maybe religion holds something for you, some mystery you just haven’t unlocked yet, or connection to a tradition you value, think about those things you have mastered, maybe in arts or sports, that came in time, with some regular practice. Think how rewarding those things are now. Maybe religion is like that. And maybe the next time you go to synagogue, you should take a bucket of balls, and not worry if you double-fault.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Mark Oppenheimer is Tablet’s editor at large. He hosts the podcast Unorthodox.

Mark Oppenheimer is a Senior Editor at Tablet. He hosts the podcast Unorthodox. He has contributed to Slate and Mother Jones, among many other publications. He is the author, most recently, of Squirrel Hill: The Tree of Life Synagogue Shooting and the Soul of a Neighborhood. He will be hosting a discussion forum about this article on his newsletter, where you can subscribe for free and submit comments.