Wearing My Father’s Tallit at the Western Wall for Me, and for My Daughter

An American explains why she’s flying halfway around the world to join Women of the Wall for their 25th anniversary Kotel prayer group

My brother smiles shyly in the photo. He glances downward, just to the right of a velvet-wrapped Torah on a table. It is a moment of benediction. The rabbi’s hand rests on my father’s forearm. My father touches my brother’s curly hair. Around this semi-circle of blessing, men gather and marvel that an American boy has read Hebrew aloud so well.

I took this photo of my brother’s bar mitzvah at the Western Wall in 1982. We held the service at the mechitza, the divider between men and women. It was low and easy to see over. I felt part of the ceremony, even if I wasn’t really. The women’s section seemed light and spacious. I loved seeing Israeli women toss candies at my brother and trill ya-ya-yas in celebration.

Today, rather than an even 50-50 split, women now have access to only a fifth of the space the men enjoy. Men chant and sing freely on their side. Women, crammed into a corner, pray silently or mouth the words on theirs. I didn’t consider this inequity my problem until the morning last summer when I visited the Kotel for the first time in 31 years, before my son’s bar mitzvah. Like my brother, he was to become bar mitzvah in Israel, just not at the Kotel: We weren’t welcome because my rabbi, a woman, wasn’t allowed to read from the Torah at the Wall.

On Monday, I’ll be back at the Wall with 150 other American women and men joining the group Women of the Wall for their 25th anniversary prayer service. We are going because the future of the Wall represents the crux of Jewish identity. “Israel is the one place where Jewish values play out,” says Anat Hoffman, the group’s chairman, co-founder, and public face. “The question is what are Jewish values? Are they tolerance, pluralism, and social justice?”

For some, like me, the journey is their first involvement with the group. For others, it’s their first foray into any kind of activism. “I’ve never done anything like this in my life,” says Sandee Holleb, a substitute teacher in Wheeling, Ill. Though Holleb once lived in Israel and has long supported her synagogue, she’s never put herself physically on the line this way. “As an American, I was brought up with the inalienable right to worship as I choose,” she says. “It’s a message that we as Americans take for granted.”

***

It wasn’t always like this at the Western Wall. One historic photo shows women and men praying there, without a barrier, in 1929. The first divider popped up in 1967, after the Wall returned to Jewish hands following the Six Day War. Reform Jews planned to hold a mass thanksgiving prayer there at the end of the International Reform Conference in Jerusalem. A group of ultra-Orthodox rabbis got wind of the plan for men and women to pray together, protested to the prime minister and—presto!—the barrier appeared.

The government then appointed Rabbi Yehuda Meir Getz, a soldier and the scion of a Tunisian rabbinic family, to oversee the site. Though some considered Getz moderate compared to other Orthodox leaders, Getz’s decisions included forbidding an army ceremony at the Wall because men and women would be standing together.

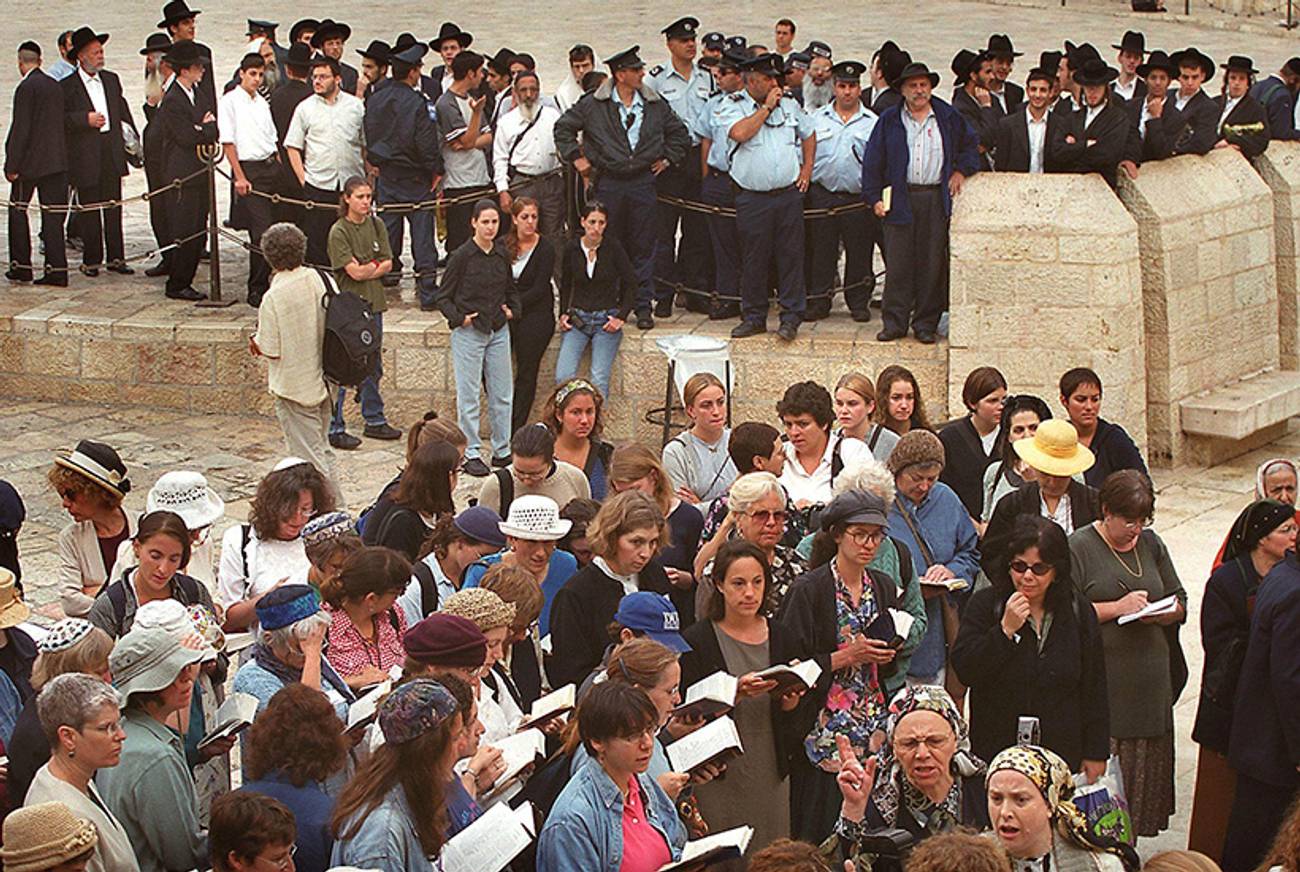

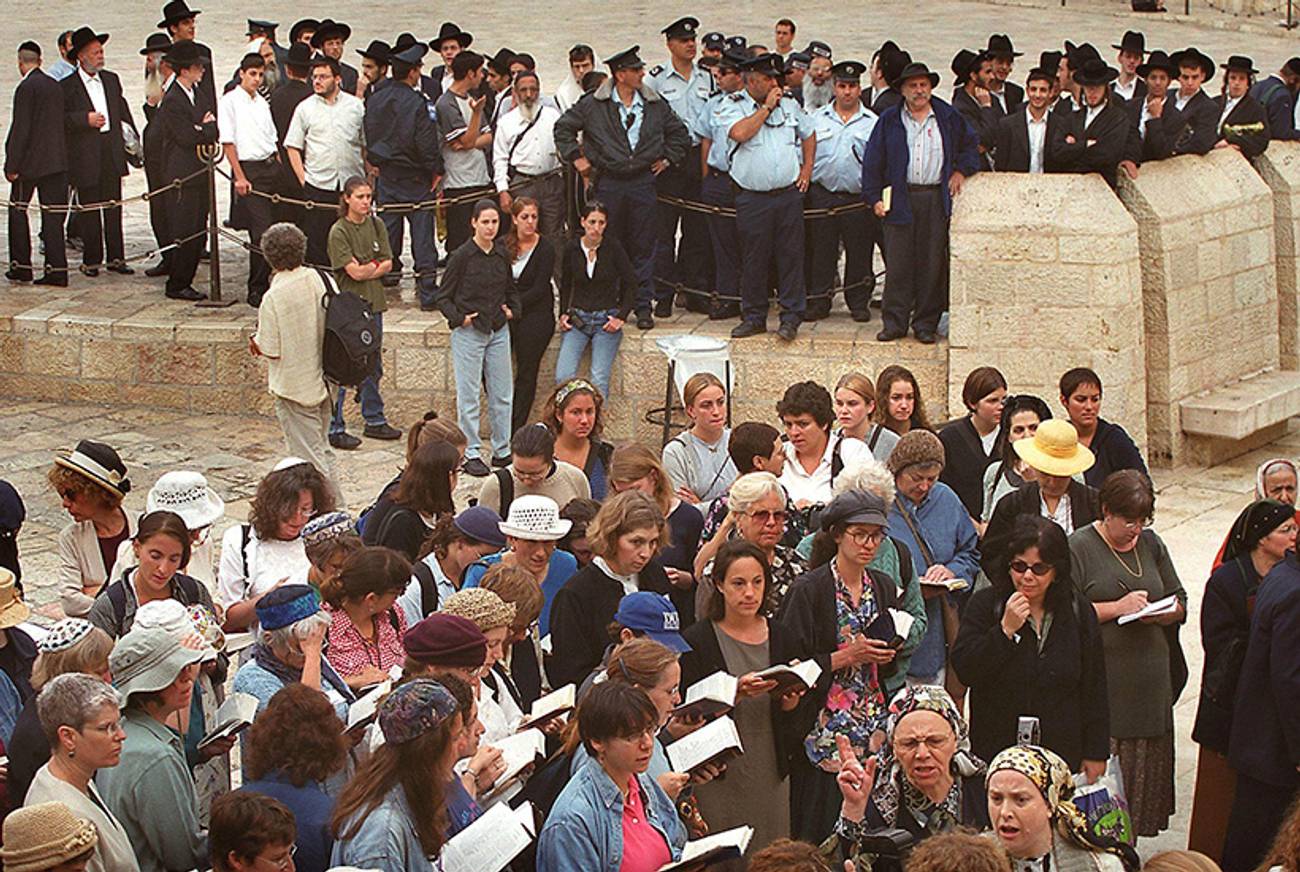

The situation at the Wall wasn’t politically charged when I visited in 1982. By 1988, that had changed. The American Orthodox feminist activist Rivka Haut organized a gathering of women to pray at the Wall during “The Empowerment of Women,” the first international Jewish feminist conference, sponsored by the American Jewish Congress. Participants included Anat Hoffman and the late feminist politician Bella Abzug. Though Women of the Wall’s official history recounts that the group was received with screams, curses, and threats from some women and men at the Wall, the prayer was still a success to the women who were there, says Bonna Devora Haberman, a Jerusalem-based educator, theater artist, and author of Israeli Feminism Liberating Judaism: Blood and Ink. “We did finish reading from the Torah,” Haberman said. “I wore my tallit.” The group felt a spiritual high, being able to pray together and read from a Torah scroll at that holy place.

Haberman decided to create an ongoing women’s prayer service at the Kotel on Rosh Chodesh—a time traditionally associated with women. The goal, she says, was to inaugurate the Kotel “for women’s full public leadership and participation at the core of Jewish sacred space.” Haberman brought about 25 women. This time, things didn’t go as well. Haredi men and women burst through the mechitza and poured in through the back entrance to the women’s section. Haberman was nine months pregnant. She grabbed the Torah just before the protesters overturned the table where the Torah had been placed. Prayer books spilled on the ground. The women encircled each other and the Torah and eased out of plaza, surrounded by people cursing them.

Women of the Wall launched its first lawsuit against the government the following year, in 1989, after a group of women attempted to pray together at the Kotel but was prevented from doing so. “Our attorney told us up to that point there were no laws regulating conduct at the Kotel,” Haut says, but soon afterward the state enacted a resolution banning most of Women of the Wall’s practices. Various legal challenges and decrees followed about what could and couldn’t happen at the Wall, with North American supporters providing critical funding to continue the fight.

A key Israeli Supreme Court ruling in 2003 held that Women of the Wall had a legal right to pray at the Western Wall—with boundaries. The court determined the group could pray at Robinson’s Arch—an archaeological site located adjacent to the main plaza—as long as the area was improved within one year to accommodate women’s worship. If the government didn’t make those improvements, it would have to come up with another solution to accommodate the group.

The state didn’t make those improvements. Women of the Wall kept praying each Rosh Chodesh, holding most of the service in the women’s section but reading from the Torah at Robinson’s Arch. They were occasionally asked to set up their service in other spots, including once near the toilets serving the Kotel.

In November 2009, following six years of relative quiet and 21 years of activism, a medical student was arrested for praying at the Kotel while wearing a tallit. The prayer service began uneventfully. “The davening was beautiful,” recalls Rabbi Jacqueline Koch Ellenson, director of the Women’s Rabbinic Network, who was visiting from her home in New York City. “Nobody was paying any attention to us.” When the group of about 30 decided to read from a Torah they had brought in a duffel bag, the police arrested the student, who was taken away “with the Torah scroll all wrapped up in her arms,” Ellenson recalls. The women decamped to the police station inside the Jaffa Gate to wait for the student, who was detained for three hours.

“I was devastated and furious, just stunned,” Ellenson says. “I came home and I didn’t know what to do.” She quickly figured out a plan. She reached out to several modern Orthodox women, including Haut, and drafted a letter asking people around the United States to hold special prayer services, teach, or acknowledge on Shabbat their support for Women of the Wall. Suddenly there was a broader American support network mobilizing on behalf of Women of the Wall. (American Reform and Conservative Jews would have more to get furious about six months later, when a bill was introduced placing state authority to determine the legitimacy of conversions, and therefore to determine who qualified as Jewish, in the hands of ultra-Orthodox rabbis who reject Reform and Conservative standards as too lax.)

Anat Hoffman’s arrest in October 2012 was a landmark that provoked outrage among the group’s North American allies. The prayer group was large that day—including 250 women from the American Jewish group Hadassah who were there celebrating the organization’s centennial—when Hoffman was arrested for “disturbing the peace and endangering the public good,” she wrote supporters shortly afterward. She described being pulled along the ground by her wrists, strip-searched, shackled by the hands and feet, and left to sleep on the floor of a jail cell with nothing to keep her warm but her tallit.

By December, when the New York Times published an article on Women of the Wall, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu realized he had a full-blown public relations problem with American Jews. Three days after the first story, the Times reported that Netanyahu had asked Jewish Agency Chairman Natan Sharansky to devise alternatives to make the Wall more open to all. American Jews’ concerns apparently caught the attention of the Israeli government in a way that 20 years of protests by Israeli women had failed to do.

***

Like movements from the Arab Spring to Occupy Wall Street, the American delegation to Jerusalem this week is happening in part because of social media. In May, my rabbi, Judy Schindler—the daughter of Rabbi Alexander Schindler, one of the great leaders of American Reform Judaism—began thinking about a trip in support of Women of the Wall’s 25th anniversary. It turned out rabbis in suburban Chicago and Dallas had similar plans, and they decided to band together on Facebook. “This mission awakened people’s passion,” Schindler says. “Those coming knew immediately that this was the trip for them. We just had to put it out there and people instantly said they were coming.”

The anniversary comes at a critical time for the group. Women of the Wall achieved a historic victory in April when Jerusalem District Court Judge Moshe Sobel ruled that the women’s prayer was not “contrary to local custom” and that women do not disturb the public order when they pray out loud wearing tallitot at the Wall. The police agreed to follow the ruling, and arrests at the Wall stopped. Yet today, post-Sobel, it remains difficult for women to read from the Torah at the Wall. Rabbi Shmuel Rabinowitz, rabbi of the Western Wall, has issued instructions forbidding visitors from bringing a Torah there. The men’s section has plenty of Torahs already provided; the women’s has none. Rabinowitz has denied Women of the Wall’s requests to donate a Torah to the women’s section or use one from the men’s side, according to several Women of the Wall officials.

Now Hoffman has agreed for the first time to negotiate with the Israeli government to create a third, equal section of the Wall at Robinson’s Arch, along the southern end of the main Western Wall. If their demands are met, the group would relinquish the right to pray in the women’s section. Among their specific demands, issued earlier this week: The space will be accessible from the main plaza, open 24 hours a day, and run by an administrative body that supports pluralistic prayer. There will be enough room for 500 people and access so visitors can touch the Kotel. Women of the Wall officials envision families praying together in the new space, women praying in groups aloud in tallit and tefillin if they choose, and girls celebrating their bat mitzvahs. The space would incorporate a removable mechitza, allowing Orthodox women and women’s prayer groups such as Women of the Wall to pray separately from men. While purportedly this can already happen in the women’s section, there’s a significant difference, Women of the Wall argues: Violence and protests against women’s prayers will not be tolerated in the new section.

The negotiations have sparked discord among longtime members of the group. Twenty women, including Rivka Haut, Bonna Devora Haberman, and Phyllis Chesler, who co-founded the International Committee for Women of the Wall, have publicly called for the board to withdraw its agreement to negotiate for a third section, arguing that such negotiations would be tantamount to abandoning the goal of full prayer rights for women at the Wall. “Women of the Wall stands for a desire to pray at the Kotel and only at the Kotel,” says Chesler, “and not at some place that you trickily say, ‘Well, it’s the Wall. It’s like the Wall. It’s close enough to the Wall. It might as well be the Wall.’ ” She sees the new spot as simply a place for those in charge of the Kotel to stick Jews whose prayer practices they don’t tolerate.

A third egalitarian section may not meet the needs of modern Orthodox women, even with a mechitza that could be added as needed. As Haut puts it, “It is not the site of our ancestors’ dreams and hopes, not the site sanctified by Jewish hearts and prayers for many centuries.”

But Hoffman argues that, after a quarter century, conditions are as favorable as they are likely to be within the Israeli government for change, and it’s time to reach a resolution. “When we started, we were just married,” Hoffman says. “Now we’re grandmothers. We thought at the time our babies would have their bat mitzvahs at the Wall.”

I understand both sides of the debate. I want women to be able to pray together and read Torah in the women’s section. But I can imagine the new section as beautiful and holy, too, a place where I would linger and feel at home. Perhaps I’ll feel differently once I’m there. But as for now, I’m planning to fly halfway around the world to support all of Women of the Wall, irrespective of the final outcome.

On Monday at 8 a.m., we will let our voices ring in prayer with hundreds of Israeli women and likely individuals from other countries as well. I’ll be there, with the simple blue-and-white prayer shawl my great-grandfather gave my father for his bar mitzvah in 1945. My brother wore it at the Wall in 1982, my son wore it in Jerusalem last summer, and now, the shoulders it rests upon will be mine. My goal is to remind the Israeli government that the Kotel belongs to every Jew—as a symbol of faith and peoplehood, a place of meaning and pilgrimage, and a setting where each Jew should have the opportunity to feel connected, not alienated. I long for a Kotel where Israel’s female soldiers are free to sing Hatikvah during their swearing-in ceremonies, and where my daughter might pray in the same way as my son.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Andrea Cooper is a writer based in North Carolina. She has written for Time, Salon.com, Utne Reader, Pacific Standard, National Geographic Traveler, and Vogue, and has contributed to NPR’s All Things Considered.

Andrea Cooper is a writer based in North Carolina. She has written for Time, Salon.com, Utne Reader, Pacific Standard, National Geographic Traveler, and Vogue, and has contributed to NPR’s All Things Considered.