Do Jewish Children’s Books Have a Problem With Gender?

Girls and women have long been relegated to domestic roles—when they’re included at all. But that may finally be changing.

The Longest Night: A Passover Story, written by Laurel Snyder and illustrated with beautiful watercolors by Catia Chien, retells the Passover story through the eyes of a young slave girl. On Tuesday, The Longest Night won the 2014 gold medal in the Sydney Taylor Book Award’s young readers category. Presented annually since 1968 by the Association for Jewish Libraries and named in memory of the beloved author of the widely read classic All-of-a-Kind Family series, the award honors books that have made a distinguished contribution to Jewish children’s literature.

This year’s award also seems to signal a new trend in young Jewish children’s literature that highlights the experiences and stories of Jewish girls. In 2011, Hannah’s Way received the same award, and together these two books mark an important shift in the gender politics of Jewish children’s literature, which has tended to disproportionately feature stories of Jewish boys.

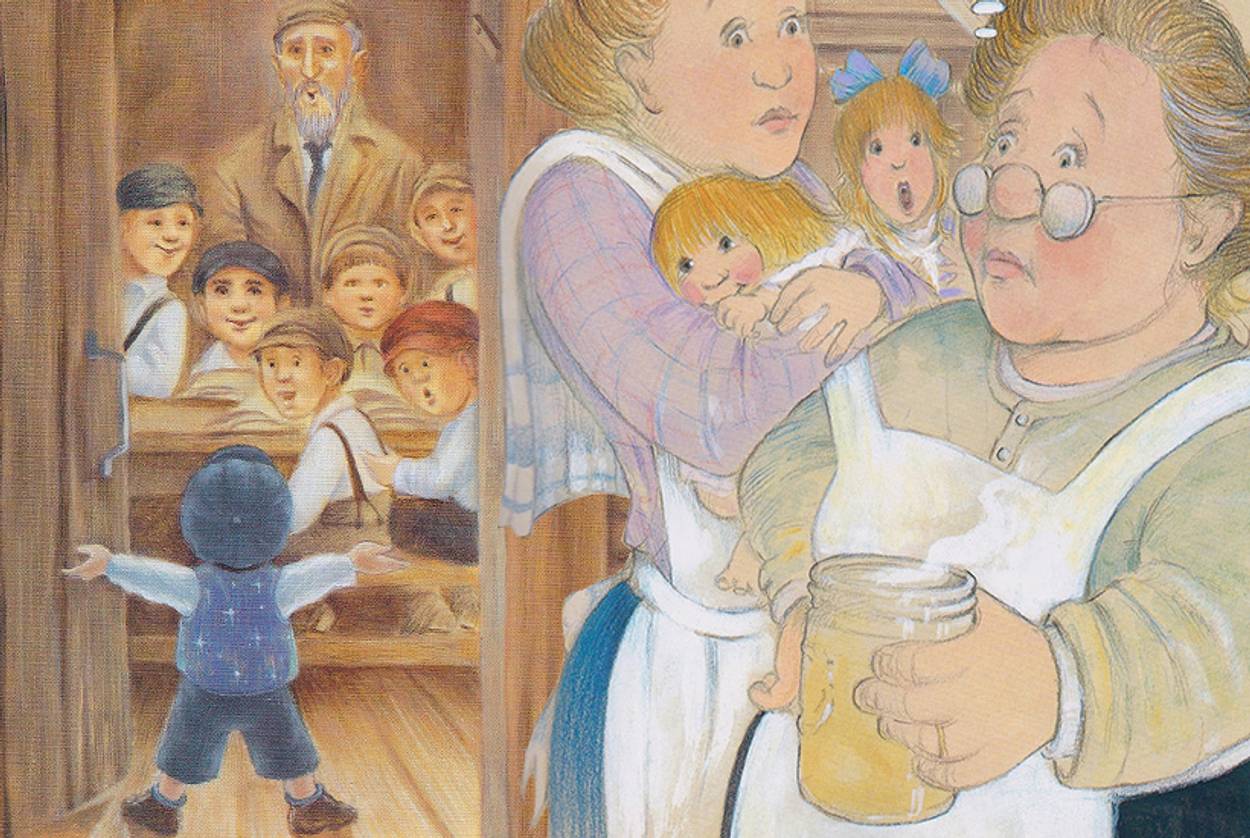

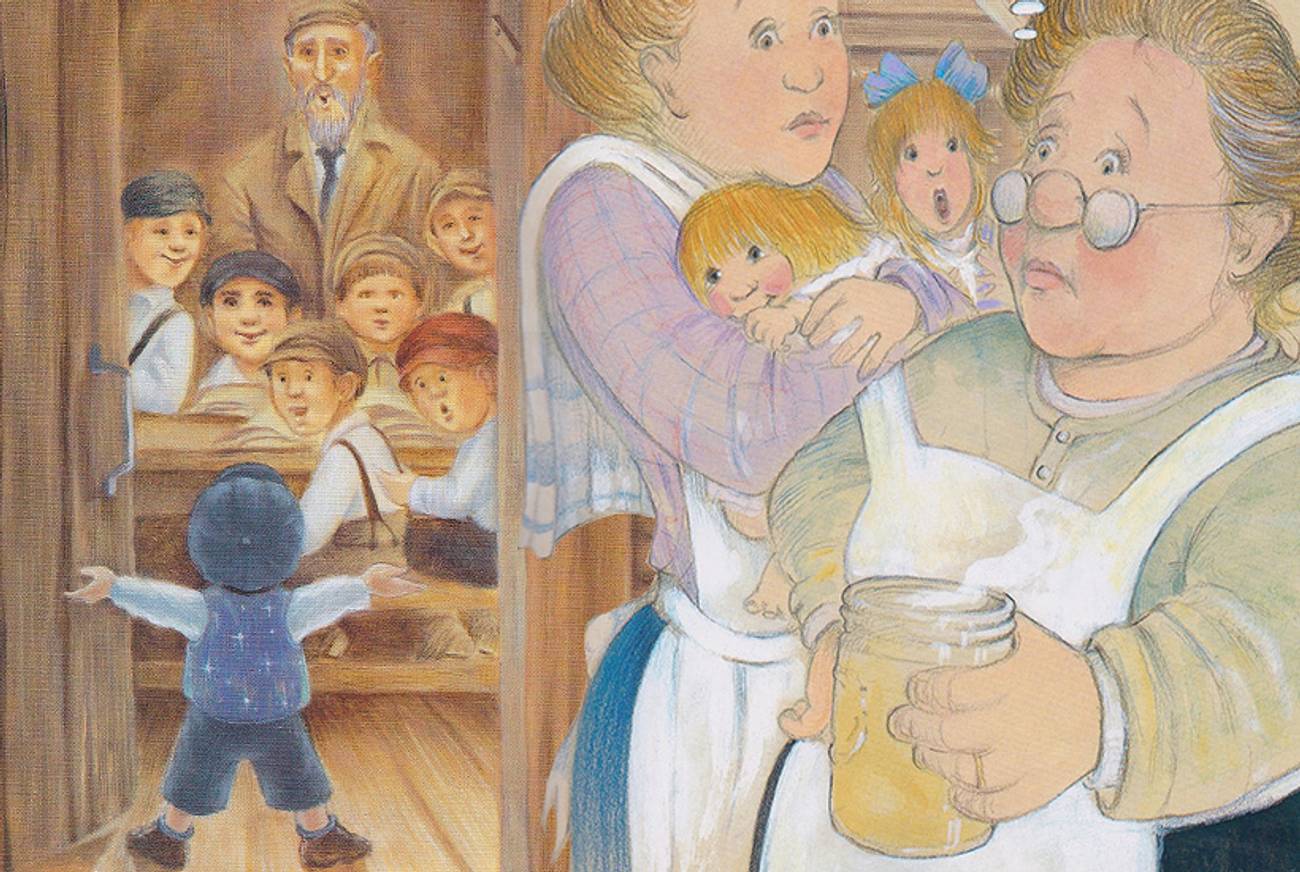

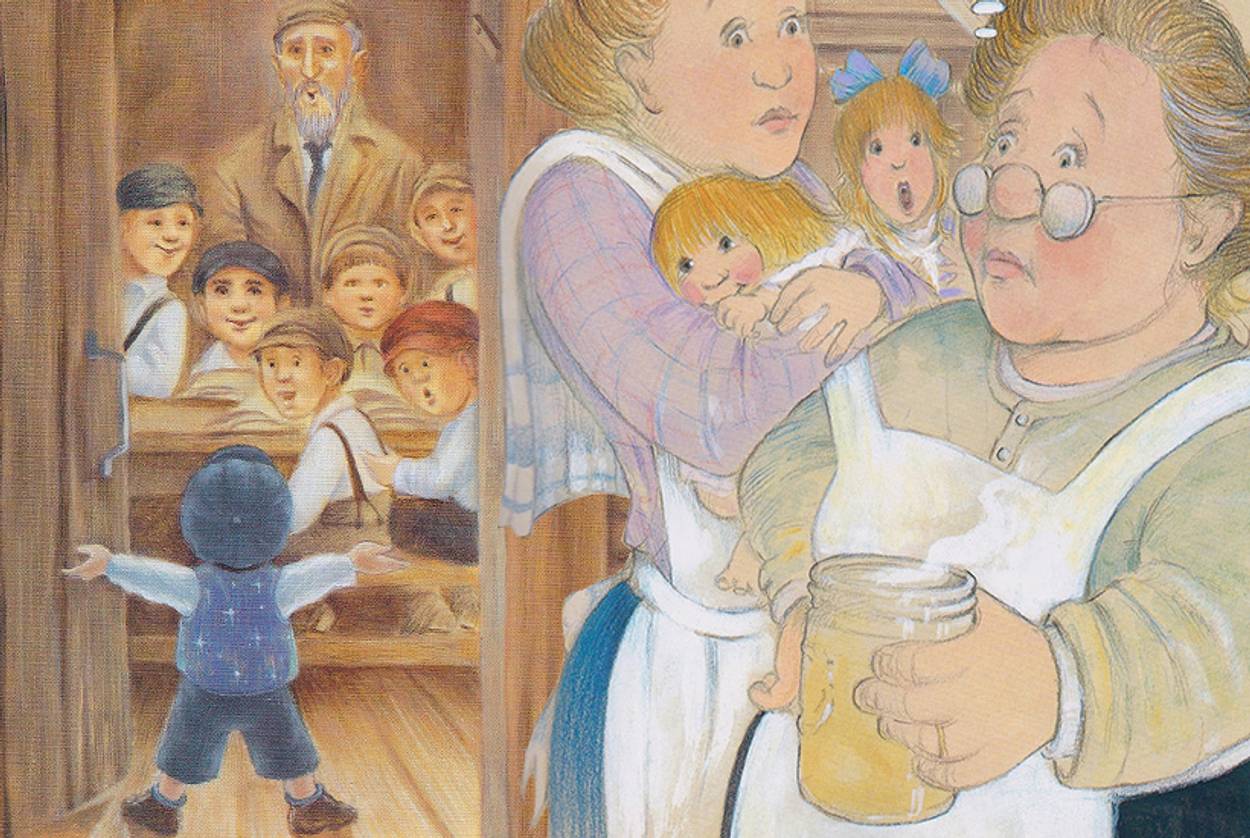

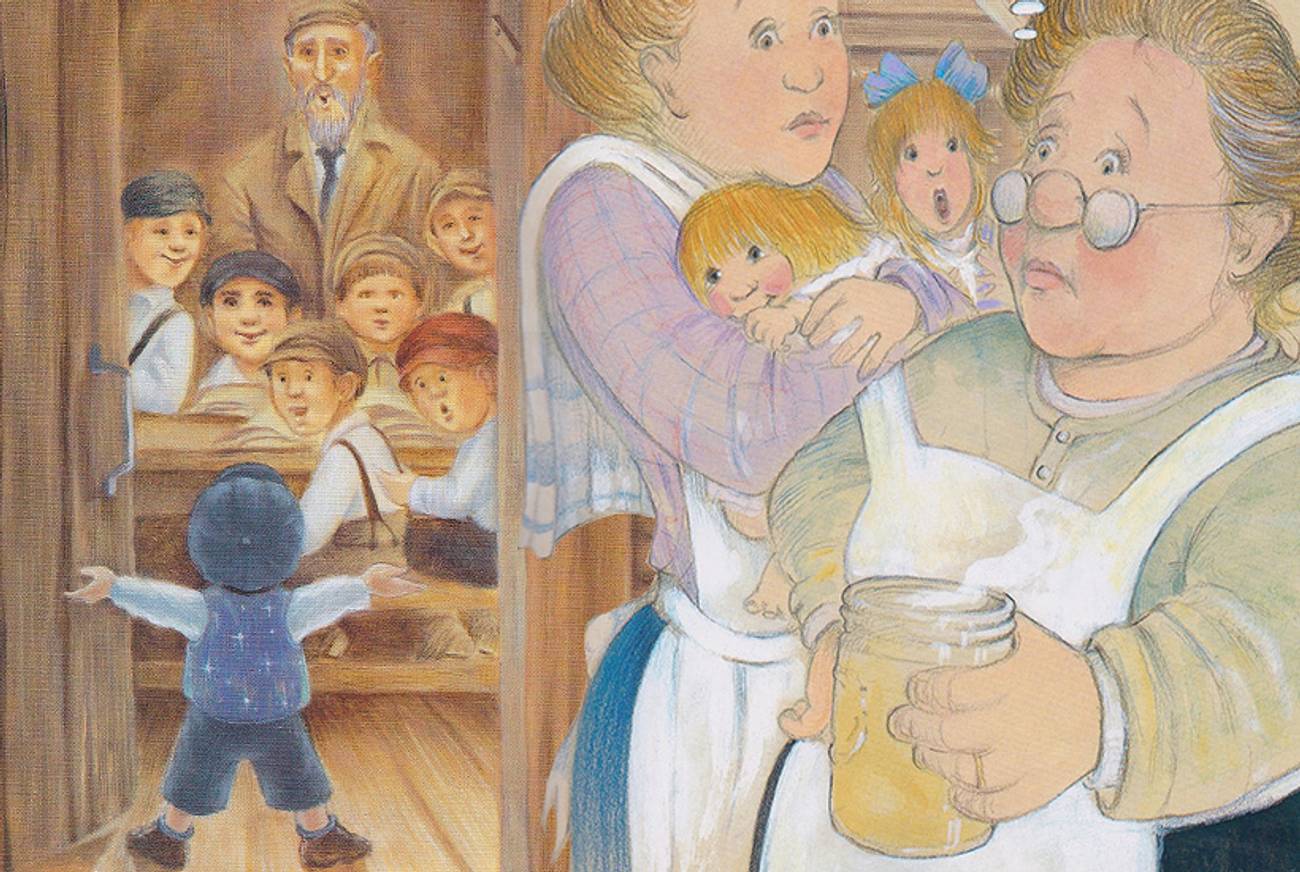

I first started thinking about the gender and Jewish children’s literature one evening in 2011. As part of our nighttime ritual, I read a book with my young daughter before tucking her into her bed: Something From Nothing, which won the 1992 Sydney Taylor Award. An endearing adaptation of a Jewish folktale, it’s about the love between a little boy named Joseph and his grandfather, a tailor. The book begins when Joseph was a baby and his grandfather sewed him a blanket to keep him warm. Over the years, the blanket grew ragged, and Joseph’s grandfather turned it “round and round” with his scissors and sewing needles and eventually transformed the blanket into a jacket, and then a vest, then a tie, a handkerchief, and finally a button. The only female character is Joseph’s stony mother, whose refrain is: “It is time to throw it [the blanket/jacket/vest/tie/handkerchief] out!”

I started wondering what types of stories were written about and for Jewish girls and what other images of the Jewish mother were promoted in Jewish children’s literature. I joined forces with my colleague Nicole Fox of Brandeis University, and together we examined the representations of gender and family life in all the young-reader winners of the Sydney Taylor Award from 1980 to 2011—a total of 30 books. We analyzed the illustrations and texts in these books, wrote descriptive summaries, and kept track of male and female visibility, parent-child interactions, division of household and occupational labor, religious practices and rituals, and other measures of gender and family life. Our findings, forthcoming in the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, paint a troubling picture for those committed to gender equality in the Jewish community.

We found a clear disparity in the representation of female versus male characters in these award-winning books. Males were represented nearly three times as often in the titles and central roles. And, of those books that included children, 1.6 times as many books featured more male children than female children. Although we paid careful attention to change over time, we did not find that patterns or trends varied appreciably by decade. The implications of our findings for the Jewish community seem clear: These books transmit the message that Jewish female characters are less valuable than their male counterparts, which has the potential to contribute to a general sense of unimportance among Jewish girls and privilege among boys.

Perhaps more troubling than the dearth of central female characters in these books, however, is how women are presented when they do appear. We found that these books, when taken together, promote the image of the domestic Jewish woman—and no other. The lives of the women in these award-winning books revolved around raising children, keeping house, and quietly performing Jewish rituals, particularly Sabbath mitzvot (lighting candles and baking challah) within the confines of the home. Jewish women did not engage in any ritual text or Hebrew study (men certainly did), nor did they attend synagogue on the Sabbath, though they did occasionally attend with their families on holidays or for funerals. Women were always represented as wives or mothers (while men were shown occasionally as single or childless), and Jewish mothers engaged in cooking, cleaning, and nurturing behavior far more often than the fathers. Women, both mothers and grandmothers, were not portrayed as working outside of the home or having a career in any of these books, with the exception of one woman who sold baked goods during the holidays.

The opening-scene in Rivka’s First Thanksgiving, which won the gold medal in the young reader category in 2001, illustrates some of the domestic activities of Jewish women in our sample. Set in the Lower East Side of Manhattan in 1910, the book tells the story of a determined young girl, Rivka, and her quest to convince her Orthodox rabbi, Rabbi Yoshe Preminger, to allow Jews to celebrate Thanksgiving. In the first scene, Rivka’s grandmother (Bubbeh) and mother, both in aprons and housedresses with their hair pulled back loosely in buns, dote on Rivka and her baby sister. Bubbeh leans over Rivka as she colors at the kitchen table, helping to guide her crayon. Standing behind them, Rivka’s mother cuddles her baby sister and watches on. All four female characters are gathered together in the kitchen with laundry drying on the clothesline behind them, soup simmering on the stove at their side, and baking supplies and a recipe box resting prominently on the kitchen counter in front of them.

Fathers in these award-winning books, on the other hand, were never shown cooking, cleaning, or otherwise engaging in domestic labor. Rather, men were frequently shown holding public positions of power and religious leadership. The presentation of men in the book As Good as Anybody: Martin Luther King Jr. and Abraham Joshua Heschel’s Amazing March Toward Freedom, which won the gold medal in the young reader category in 2009, provides a clear contrast to the presentation of women in Rivka’s First Thanksgiving. As Good as Anybody chronicles the life stories of two inspirational men, Martin Luther King Jr. and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. The book draws a parallel between these men’s experiences with discrimination and persecution, their commitment to learning and righteousness instilled by their fathers, and their rise to positions of leadership. The book closes with their famous walk together in the 1965 civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Ala. Rivka’s First Thanksgiving conveys the message that the lives of Jewish women revolve around domestic work; As Good as Anybody transmits the message that Jewish men are and can be learned, powerful, and prominent leaders.

The characterization of men in As Good as Anybody is consistent with their depiction in other award-winning books. We found that 13 books showed men as religious leaders versus one book that showed a woman as a religious leader. Men were routinely shown leading religious services as a prayer leader or rabbi, blowing the shofar on Rosh Hashanah, teaching children Jewish texts, or performing Jewish rituals like conferring upon a boy his status as a bar mitzvah or leading a funeral service. Despite the fact that women constitute a significant percentage of American rabbis, the rabbis in these award-winning books were talked about and shown as men in every instance.

It is important to note here that our study is not centrally concerned with whether or not the stories in these books are historically accurate (an important but different project), but with the fact that children’s book authors emphasize the same themes and stories over others when history, and certainly children’s stories, can be told from various perspectives. At issue here then is not whether women in the Lower East Side of Manhattan at the turn of the 20th century were homemakers (many were) or whether Heschel was a prominent and inspirational leader (he was), but rather that children’s book authors make choices when they select stories. And these choices tend to paint an image of the pious, domestic woman and the public, learned man. These gender stereotypes have the potential to shape the way boys and girls relate to themselves, each other, and to Judaism more generally.

The one book that is the stark exception to the rule is New Year at the Pier (2009). The story centers on a young boy, Izzy, and his readying for the tashlich service on Rosh Hashanah by reflecting on his behavior and apologizing for his wrongdoings. The story concludes when Izzy and his family (which includes his mother and sister Miriam) gather with the community at the pier to symbolically cast away their sins by throwing bread into the water. The book has a very clear egalitarian and progressive bent: The cantor is a woman, she plays the guitar on Rosh Hashanah, only some men wear kippot, many women wear pants, the rabbi and cantor are called by their first names (Rabbi Neil and Cantor Livia), and Izzy’s mother seems to be a single parent.

I recently spoke to April Halprin Wayland, the author of the book, and she told me that her secular Jewish background shaped her thinking about the plot and cast of the story. Although Wayland deliberately sought out a secular publishing house for this book—Dial Press—rather than a Jewish publishing house, she did take measures to try to make the book appeal to more observant Jews: She changed the language (synagogue rather than temple); changed the timing so that the main characters were not writing on Rosh Hashanah; and deliberately left out the word God.

When I asked Wayland if she was aware of the gender imbalance in Jewish children’s literature, she told me that it was on her radar. She had originally planned to write the book from the perspective of Miriam, Izzy’s older sister, but her publisher wanted the book written from a younger point of view, so young Izzy took center stage. Wayland told me that in the past, “the unstated or sometimes stated wisdom is that girls will read books that star boys but boys will not read books that star girls.” She continued, “Books that feature boys are easier to sell … we [authors] try to work in the framework of market. Compromise is so painful.”

One arena where compromise—or even dialogue—was not allowed was between author and illustrator. A highly regarded, non-Jewish Canadian illustrator, Jorsich had complete autonomy over his drawings. And he drew Izzy’s mother as a thin, smartly dressed woman with straight, jet-black hair and dark eyes, a look staggeringly different from that of all the other mothers in our sample of award-winning books. We assumed that Izzy’s mother was Asian—a fair assumption according to Wayland, who herself thinks that Izzy’s mother looks Japanese. Of all the books in our sample, this was the only instance where a Jewish woman (or man, for that matter) looked possibly non-white. Although not the topic of our study, it is worth noting that none of the books in the sample contained any diversity in terms of race, ethnicity (no books featured a non-Ashkenazi family, for example), or sexual orientation (no books featured a same-sex couple or gay family member).

When I asked Aimee Lurie, the chair of the Sydney Taylor Award committee, if she was surprised about the gender imbalance in Jewish children’s literature, she told me many of the recent Sydney Taylor Award honorable mention and notable books, which were not included in our sample of gold medalists, do include “positive depictions of women.” She explained that the award committee is committed “to recognizing outstanding literature with Jewish content for children and teens. … The selection of winners and honor books is based solely on the pool of titles submitted during the calendar year. We [the committee] do not compare the style, content, subject matter, illustrations, or character gender of current submissions against past year winners.”

In the future, Lurie told me, she hopes that “publishers and authors will create stories that not only reflect the Jewish experience and resonate with all readers but also include depictions of women that reflect current standards of gender roles. It is my sincere hope that books like Hannah’s Way (2011) and the other [honorable mention and notable books] are proof that publishers and authors are moving in the right direction.”

If The Longest Night is any indication, the next 30 years of Jewish children’s books may look different from the past 30.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Emily Sigalow is a doctoral candidate in the departments of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies and Sociology (joint program) at Brandeis University.

Emily Sigalow is a doctoral candidate in the departments of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies and Sociology (joint program) at Brandeis University.