Thou Shalt Not Covet Thy Brother’s Wife. Unless He Dies. Then—Well, Here’s the Thing…

In this week’s ‘Daf Yomi,’ questions of obligation in matters of levirate marriage, and how values change with time

Literary critic Adam Kirsch is reading a page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

In my last column, I discussed the rabbis’ edict that converting to Judaism in order to marry a Jew is forbidden. The principle behind the rabbis’ thinking was that, if you are going to take up the considerable responsibility of following Jewish law and sharing the Jewish fate, you must do so only out of a desire to serve God and not to obtain any personal benefit—even one as altruistic as marrying someone you love. In this week’s Daf Yomireading, this same principle was invoked in a different context, when the rabbis considered the possible motives that might lead a man to contract a levirate marriage with his yevama, his deceased brother’s wife.

Since the beginning of Tractate Yevamot, we have been dealing with questions of obligation. If a man is married but childless and he dies, his brother is obligated to the widow: He must either marry her, in order to continue the dead man’s family line, or else he must release her by performing the ceremony of chalitza. The assumption underlying the discussion is that this is a rather burdensome duty, which the brother might well want to escape. Thus, in Yevamot 39a, the mishna outlines a situation in which the oldest surviving brother refuses to consummate the levirate marriage. In that case, the duty passes to each of the dead man’s younger surviving brothers, in order of age. If they all refuse to marry the widow, then the oldest brother is compelled either to perform chalitza or to go through with the marriage. The rabbis even envision the responsible brother making excuses to put off this obligation. He might try to fob off the widow on another brother who is absent on a journey, saying that she should wait until he returns; or he might turn her over to a brother who is a deaf-mute, urging her to wait until he recovers from his affliction. Such excuses, the rabbis rule, are invalid. But the very idea that the oldest brother would go to such lengths to escape his yevama suggests that levirate marriage was an irksome responsibility.

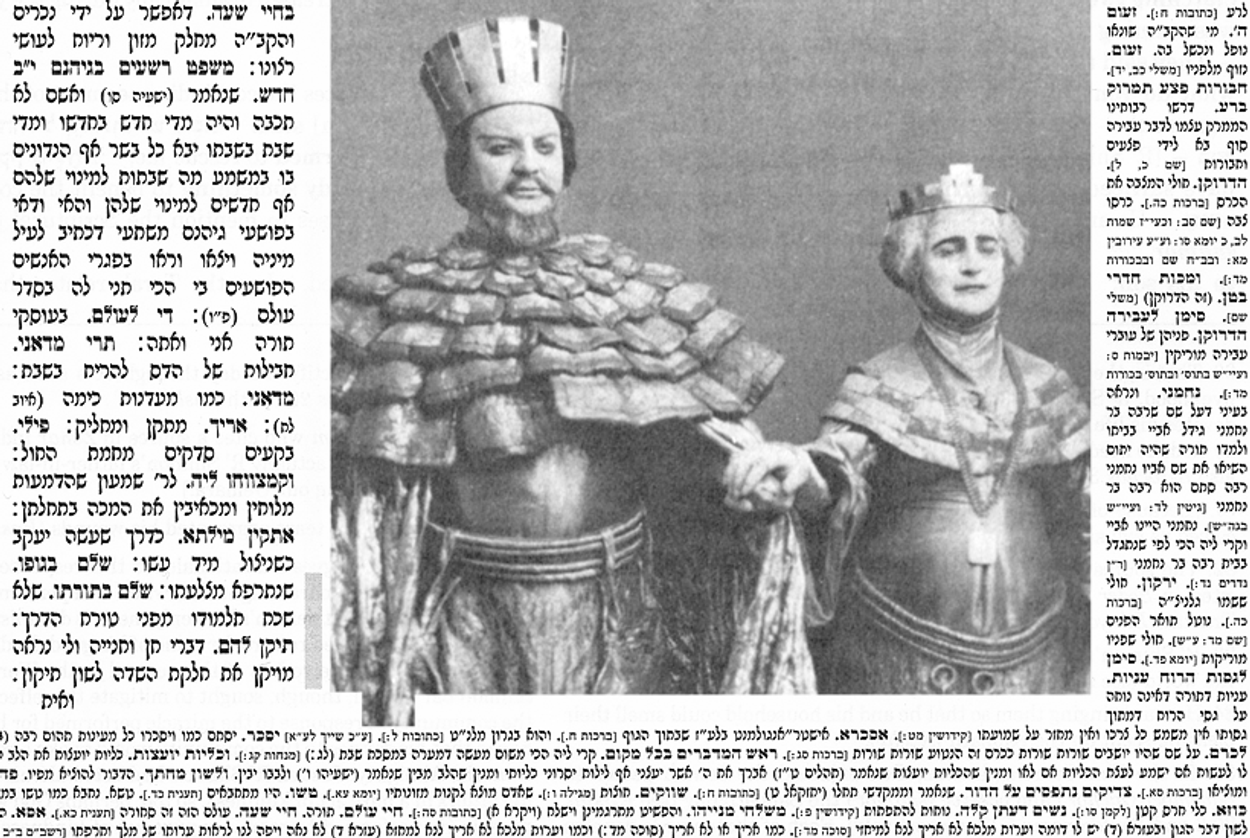

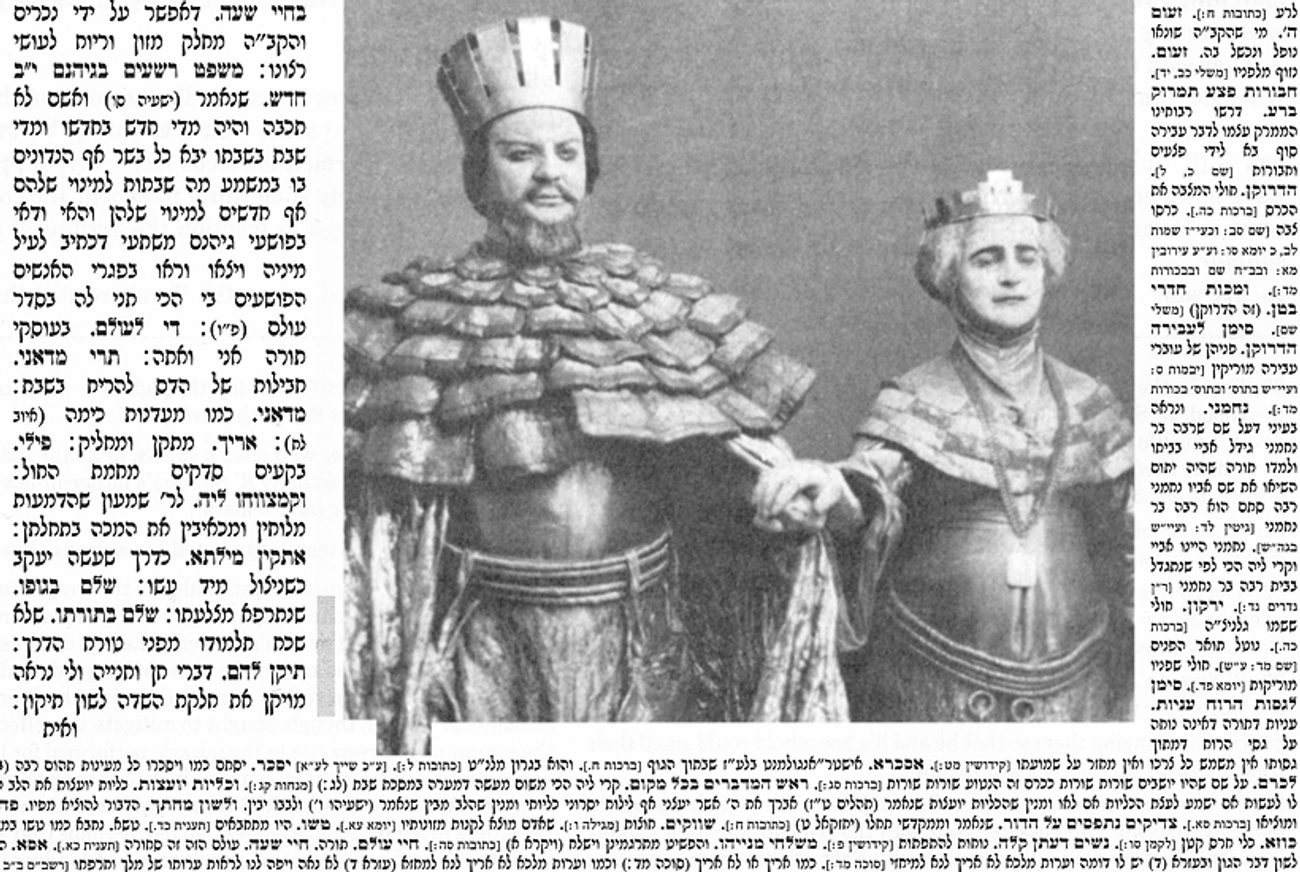

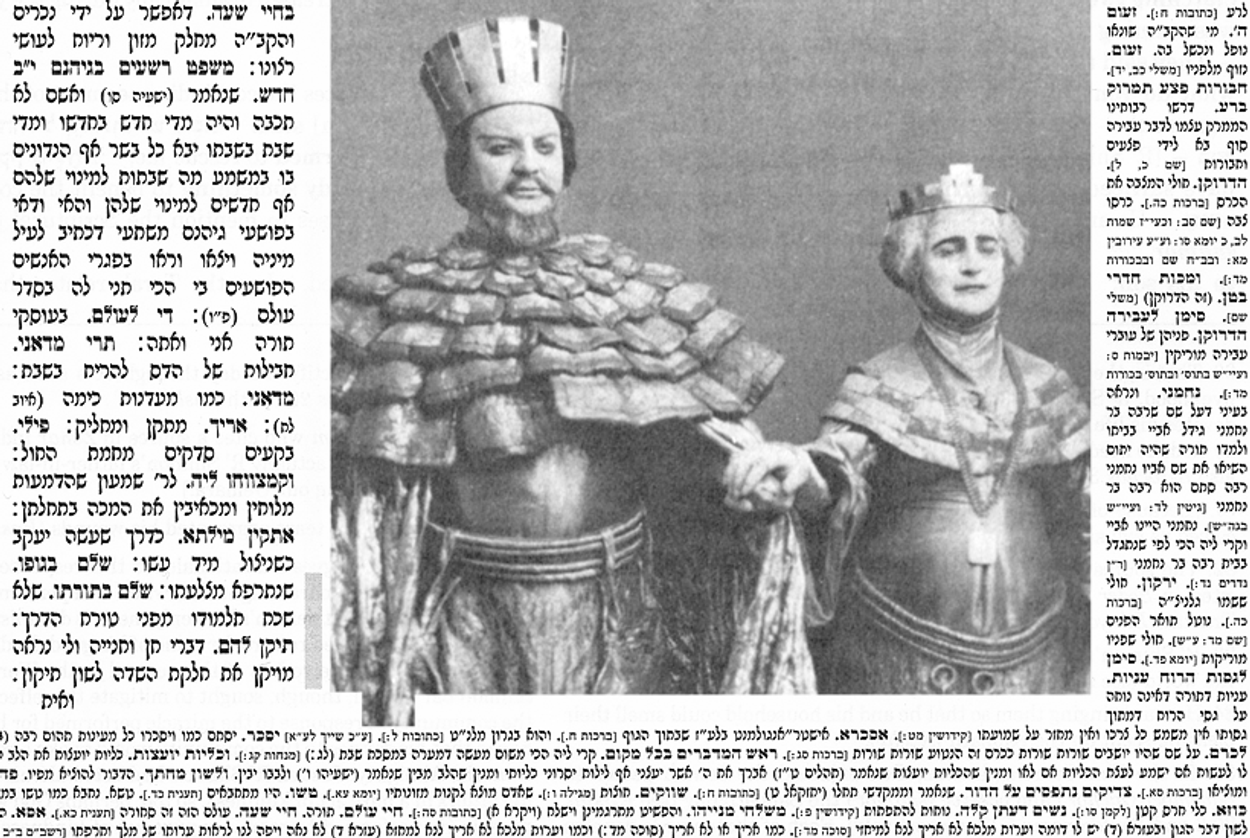

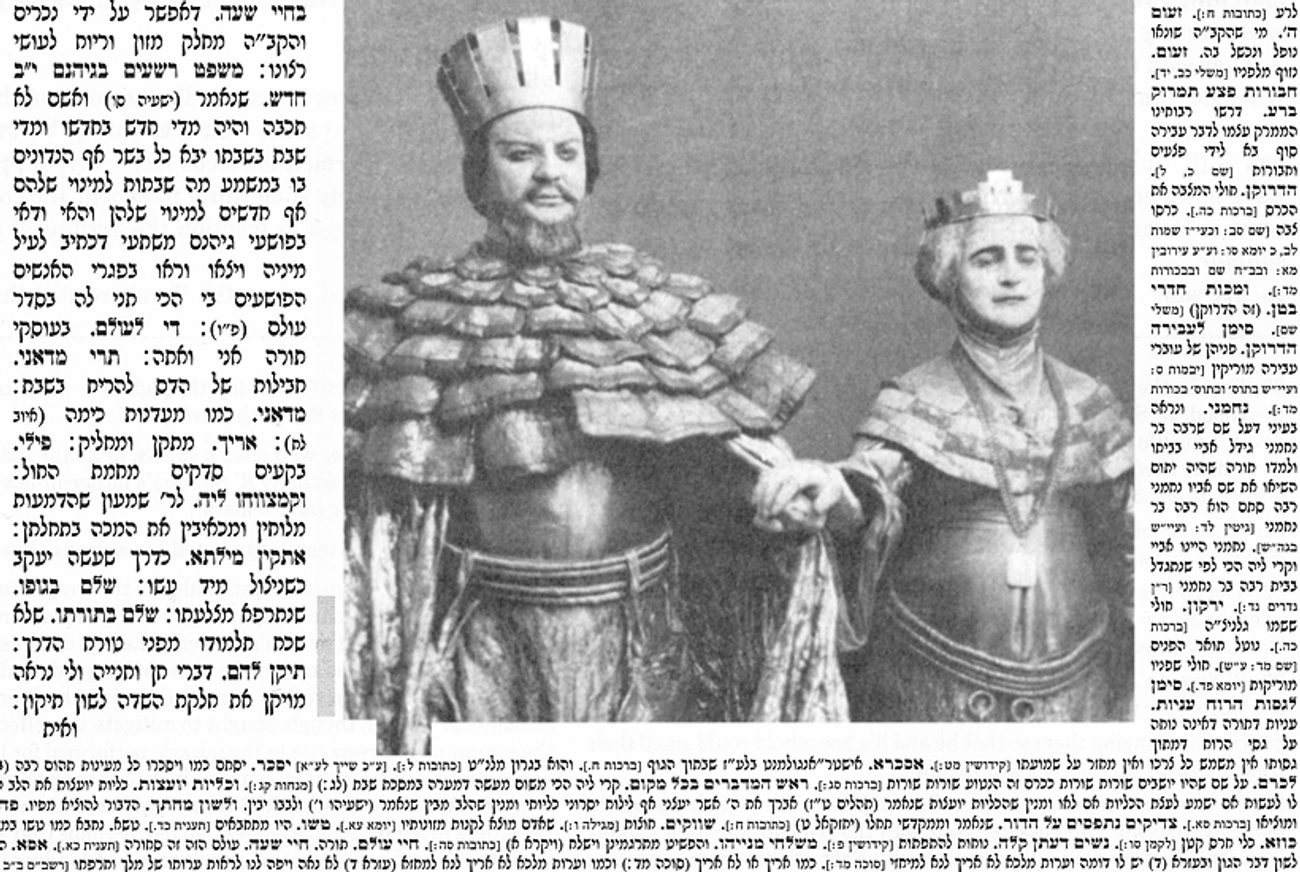

It’s possible to imagine a situation, however, in which a brother would quite like to marry his dead brother’s widow. Perhaps he had always been attracted to her and now sees a chance to get his hands on her; or perhaps he is merely interested in getting his hands on the dead brother’s property. Here we are once again faced with the question of whether it is permitted to perform a mitzvah for selfish reasons. According to Abba Shaul, the amora quoted in Yevamot 39b, the answer is a definite no: “Abba Shaul says that one who consummates a levirate marriage with his yevama for the sake of her beauty, or for the sake of marital relations, or for the sake of another motive [e.g., he wishes to inherit her husband’s estate], it is considered as though he encountered a forbidden relation.”

Remember that, ordinarily, a man is strictly forbidden sexual contact with his sister-in-law; this prohibition is suspended only in the case of levirate marriage. And the reason for levirate marriage is not to gratify the surviving brother’s desires, but to provide a service for the dead brother and to satisfy a divine commandment. Turning levirate marriage into a selfish act is just as bad as violating the original prohibition, according to Abba Shaul’s strict view. Indeed, he goes so far as to say that the offspring of such a compromised union should be considered illegitimate, a mamzer. The rabbis, however, take a more lenient view. They look at the actual letter of the law in Deuteronomy, which simply states, “Her brother-in-law will have intercourse with her.” Thus they conclude that the action, not its motive, is what matters: A levirate marriage contracted for pleasure or gain is just as valid as one carried out for duty’s sake.

Looking at the issue from this point of view, however, raises another question. The surviving brother has two courses of action open to him: He can either marry his sister-in-law or perform chalitza to release her. But are these, in fact, equally desirable and legally equivalent options, or is one course of action preferable to the other? After all, Deuteronomy explicitly commands the surviving brother to have intercourse with his sister-in-law, in order to extend the dead man’s lineage. Chalitza could be seen as a way of evading this obligation, rather than a way of fulfilling it.

As Rava explains, there are three stages in a woman’s relationship to her brother-in-law. Initially, before she is married at all, any of the brothers in a family is permitted to marry her, but none is obligated to do so. Then, once she marries one of the brothers, all of the others are barred to her; this is the second stage, when the incest prohibition renders her brothers-in-law forbidden. If her husband dies, however, she now enters a third stage, in which she is no longer merely permitted to her brother-in-law, but positively required to marry him. The point Rava is making is that the third and first stages are not equivalent: A dead man’s brother is not merely allowed to marry his widow, but required to marry her. By this logic, carrying out the levirate marriage would seem to be preferable to chalitza.

To clarify the matter, the Gemara engages in one of its favorite moves, drawing an analogy with a distant area of law. In this case, the rabbis look to the practice of the priests in the Temple with regard to eating the meal offering. (The comparison of eating flour to getting married feels slightly comic, but it’s certainly not intended that way.) Here, too, the priest goes through three stages in relation to the meal-offering. Before it is consecrated as a sacrifice, when it is just some meal in a dish, the priest can eat or not, as he pleases. Then, once it is designated a meal-offering, it is forbidden to him and he can’t eat it at all. Only in the third stage, when the meal is actually burned on the altar, does it become a mitzvah for the priest conducting the sacrifice to eat a portion of it. If the parallel with levirate marriage is allowed, then, just as eating the meal at the right time is a positive duty, so marrying the widow at the right time should be a positive duty.

In fact, the Gemara never comes to a definite conclusion about whether marriage is preferable to chalitza. Rather, this appears to be one of those areas of Jewish practice that changed over time, and the rabbis generally honor the legitimacy of the popular consensus. “Initially,” the rabbis explain, men “would have intent for the sake of fulfilling the mitzvah.” The Talmud frequently suggests that standards of holiness and piety have declined over the generations, and so it is here. In the good old days, men never married their widowed yevamot for impure, selfish reasons, only for the sake of the law. When that was the case, levirate marriage was indeed preferable to chalitza. But “now that they do not have intent for the sake of fulfilling the mitzvah,” things are different, and “the mitzvah of chalitza takes precedence over the mitzvah of consummating levirate marriage.” Indeed, in Ashkenazi tradition, chalitza became mandatory, and marrying a dead brother’s widow was de facto banned—just one example of the way Jewish law evolved away from the letter of the Torah, in obedience to the values of the Jews who lived under it.

**

To read Tablet’s complete archive of two years of Daf Yomi Talmud study, click here.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.