Talmud: We Don’t Negotiate With Terrorists

This week’s ‘Daf Yomi’ features captives, kidnappers, and extortionists; ransom, escape, and stonings—and black magic

Literary critic Adam Kirsch is reading a page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

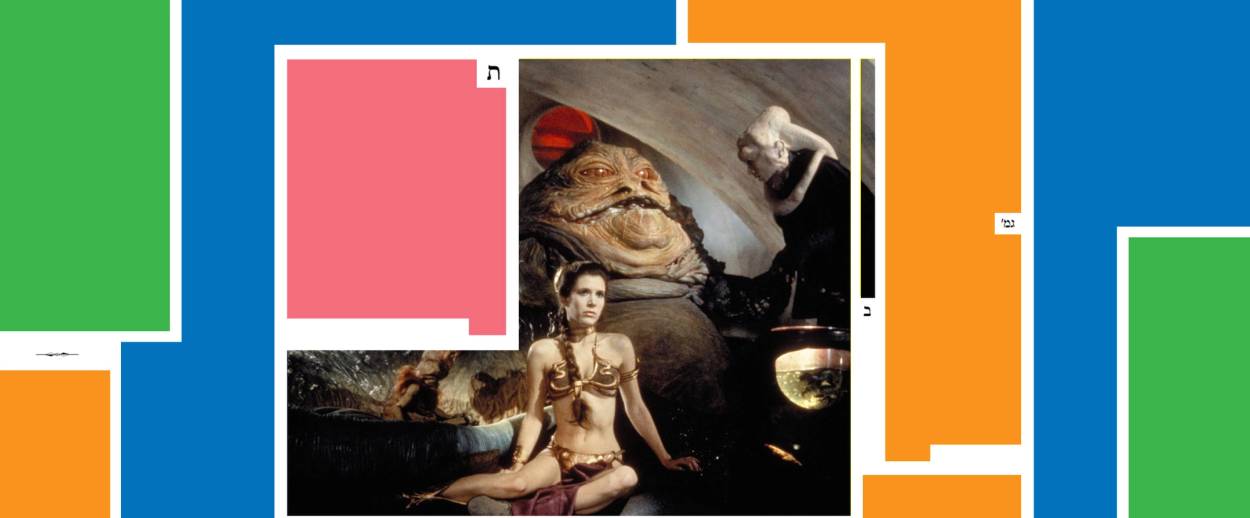

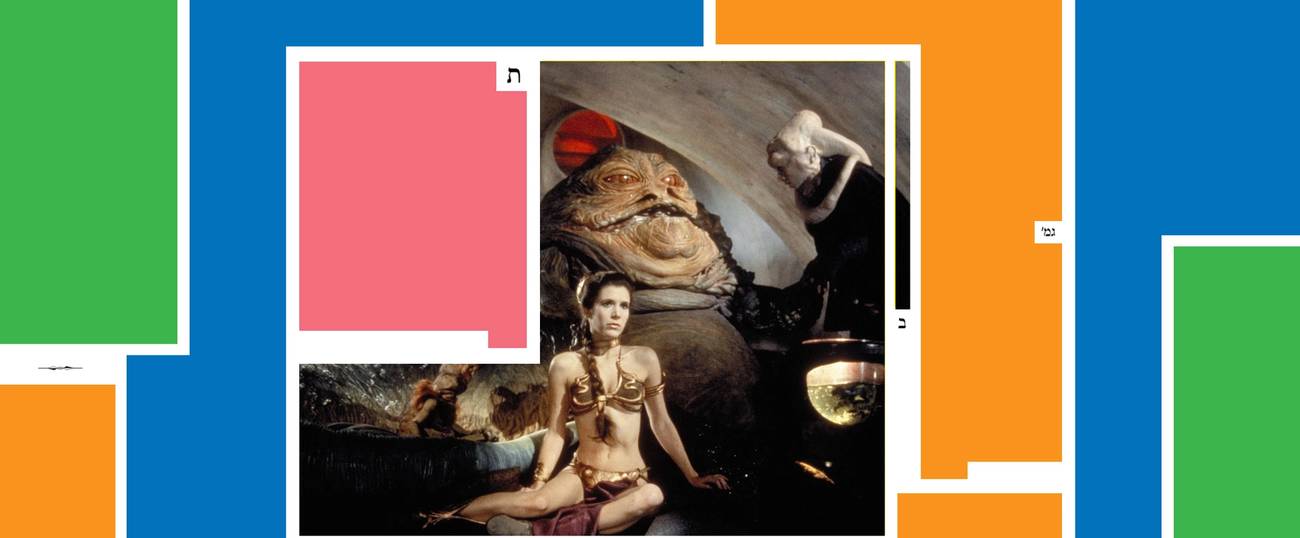

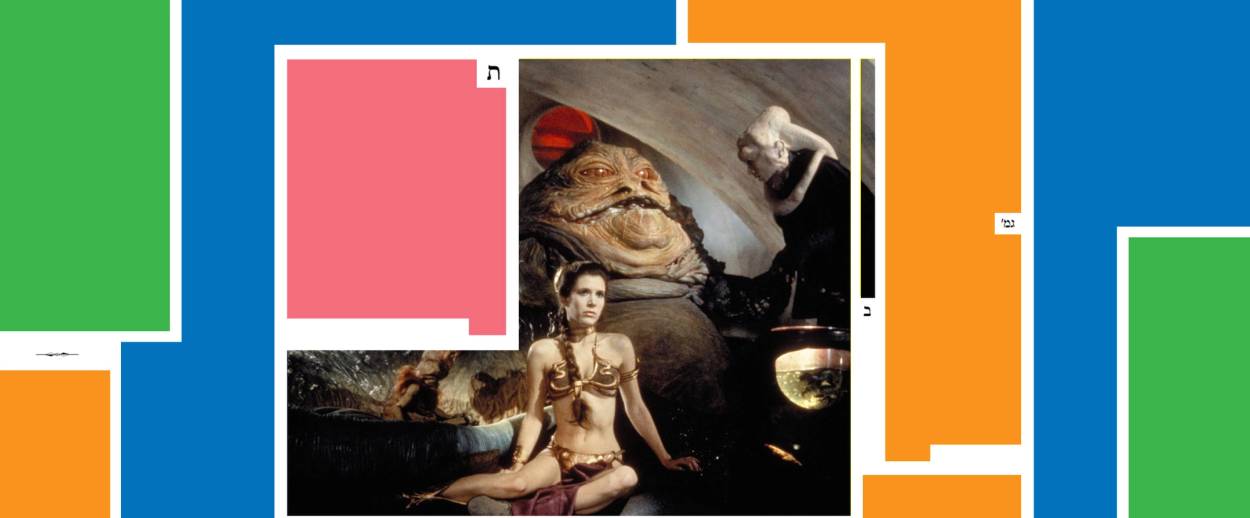

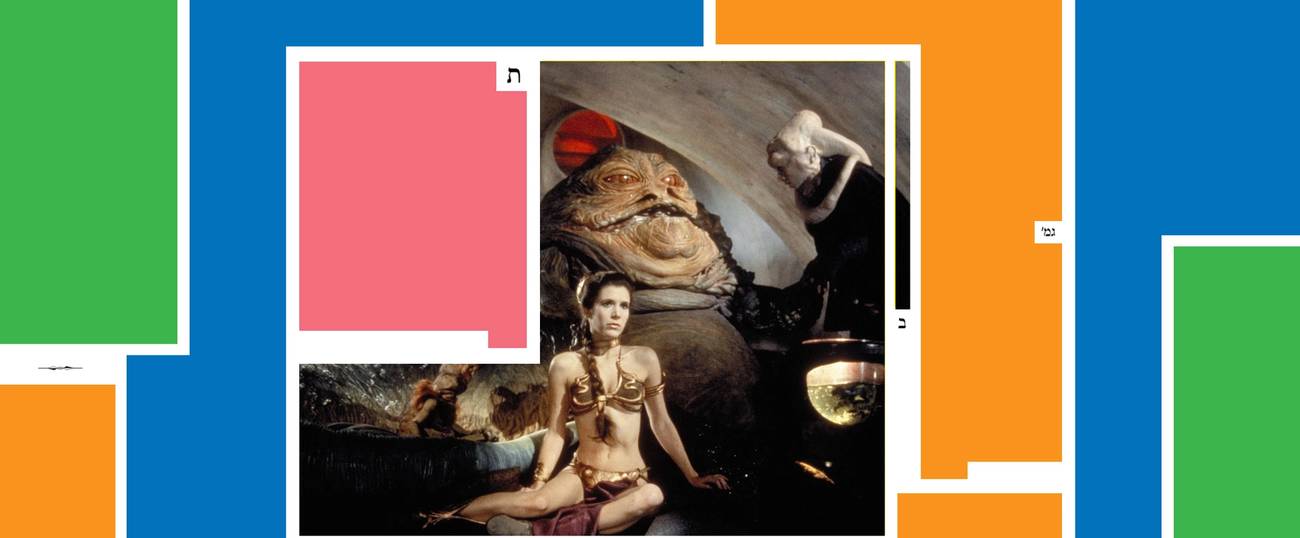

If you were to make a movie about the Talmud, the hero would have to be Reish Lakish. Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish, usually referred to as Reish Lakish, had a biography more typical of an action hero than a sage. His first career was as a gladiator in the Roman circus, before Rabbi Yochanan convinced him to devote his life to Torah. In this week’s Daf Yomi reading, in Gittin 47a, there was a story about Reish Lakish that testified to his combination of strength and cunning. Apparently, there was a tradition among gladiators that before one was put to death, he was granted any wish he asked for. When Reish Lakish was about to be killed, then, he asked he asked his captors, “I want to tie you up and have you sit, and I will strike each of you one and a half times.”

Probably they should have smelled a rat, but they agreed; whereupon Reish Lakish took a bag in which he had hidden a heavy stone and proceeded to smash them all to death. He even took the precaution of shouting at his first victim, “Are you laughing at me?” as if he were still alive—a trick to convince the others that nothing was awry. When he returned home, the story continues, Reish Lakish lived a life of pleasure, full of “sitting, eating, and drinking,” even though he didn’t own so much as a pillow to sleep on. When his daughter asked him if he didn’t need one, he replied, “My daughter, my belly is my pillow.” All in all, he sounds more like a figure from a legend—Odysseus, or Samson—than the typical amora.

Reish Lakish’s story came up in Gittin because, for a long stretch, the Gemara leaves behind divorce, the main subject of the tractate, and takes up the laws of slavery. As we saw last week, chapter 4 of Gittin brings up a number of laws that were instituted mi’pnei tikkun olam, “for the sake of the betterment of the world.” One of these has to do with the ransoming of captives, which is a major mitzvah: Jews who are enslaved or imprisoned must be redeemed by the community. (The prevalence of laws on this subject suggests how common slave-raiding and kidnapping were in the ancient world.) However, the mishna in Gittin 45a warns that “captives are not redeemed for more than their value, for the betterment of the world.”

Captives cannot be ransomed for an extortionate price; but how is this for the good of the world? The Gemara offers two alternative explanations. One possibility is “due to the pressure of the community”: If a Jewish community were required to pay any price to rescue a captive, it could be bankrupted by kidnappers. (However, it seems to be permitted for private individuals to pay any amount of ransom: The Gemara mentions Levi ben Darga, who paid 13,000 gold dinars as ransom for his daughter.) The other justification for the rule is that, if it becomes known that kidnapping Jews is a lucrative business, “they will … seize and bring additional captives.”

This is the same logic used by FBI agents in cop shows, or indeed by presidents when they refuse to negotiate with terrorists: While it is tempting to do a deal to save an individual, the common good demands that kidnapping not become a profitable industry. Reading this passage, I thought about the Israeli government’s 2011 decision to exchange 1,000 Palestinian prisoners for the captive Gilad Shalit. This sounds like it would not meet the Talmudic standard—though perhaps things are different for prisoners of war, or captives who face torture.

The mishna goes on to state a further restriction. Not only is it not permitted to pay an extortionate ransom, it is also against the law to “aid the captives to escape.” This sounds unfair—why shouldn’t people who have been enslaved or kidnapped be helped to regain their freedom? Just this debate raged in the United States in the 1850s, after the Fugitive Slave Act required Northerners to assist in returning escaped slaves to the South. But this law too, the mishna says, is “for the betterment of the world.” In the Gemara, Shimon ben Gamliel clarifies that this really means “for the betterment of the captives.” Presumably, captives would be treated more harshly—maybe confined or kept in chains—if their captors believed that they would try to escape. To avoid this, rescue attempts are forbidden.

Reish Lakish is not the only famous captive we hear about in this passage. The Gemara in Gittin 45a also tells about the daughters of Rav Nachman, who were famous for a peculiar reason: They “would stir a boiling pot with their bare hands,” without getting burned. This was generally taken to be a sign of their exceptional virtue: God protected them from harm because they were so good. But Rav Ilish was suspicious of this claim. After all, the book of Ecclesiastes disparages the virtue of women, saying, “One man among a thousand have I found; but a woman among all those have I not found.” So, how could Rav Nachman’s daughters be as good as all that?

Rav Ilish got a chance to test his suspicion when he and the daughters were all taken captive together. Ilish was given supernatural encouragement to escape—first by a raven, whose message he ignored, and then by a dove, which he trusted because “the Congregation of Israel is compared to a dove.” Before escaping, he decided to spy on Rav Nachman’s daughters: If they had remained virtuous in captivity, he would take them with him, but if they had sinned, he would leave them behind. Since, as Ilish knew, “women tell all of their matters to each other in the bathroom,” he hid out in the bathroom to eavesdrop. There he heard the women saying that they hoped they would not be redeemed, since they preferred the company of their captors to that of their husbands! Disgusted, Rav Ilish escaped without them. Now it was clear that “they would stir the pot with witchcraft”: It wasn’t holiness but black magic that allowed them to stir a boiling pot with their hands. This would be another good scene for the Talmud wide-screen epic, where some CGI would in handy. Paging Steven Spielberg?

***

To read Tablet’s complete archive of Daf Yomi Talmud study, click here.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.