Poi Story

Eating this traditional dish made from taro root is a perfect way to express what it means to be a Jew in Hawai‘i. Plus, it’s kosher for Passover.

Jewish food is hard to get in Hawai‘i, especially during Passover. It’s hard to find a can of macaroons, or a bottle of kosher-for-Passover wine, or even a box of matzo. There’s a reason that the charity cookbook put out by my shul—Sof Ma’arav, a Conservative congregation of about 60 families in Honolulu—is called The When You Live in Hawai‘i You Get Very Creative During Passover Cookbook.

Our islands are far from centers of Jewish life on the mainland, and this distance is not just physical. It is also cultural and, in a sense, existential. Our lives are different from Jewish lives on the mainland. Anti-Semitism is largely absent in Hawai‘i, because many people have no idea what Judaism is. One recent bar mitzvah featured a taiko ensemble (because, you know, it’s not a bar mitzvah without Japanese drumming). As a result, keeping kosher for Passover in the Pacific isn’t just about finding the right foods. It is also about asking how the Passover story speaks to us, what it means to be a Jew in the Pacific, and what form of Jewish practice feels authentic here.

My answer to these questions—both existential and culinary—is the same: poi. A paste made of pounded taro root, poi means different things to different people. To tourists, poi is a novelty for the adventurous. To Native Hawaiians, it’s a food central to their identity and heritage. For Jews who live in Hawai‘i, poi is delicious, healthy, filling—and kosher l’pesach.

***

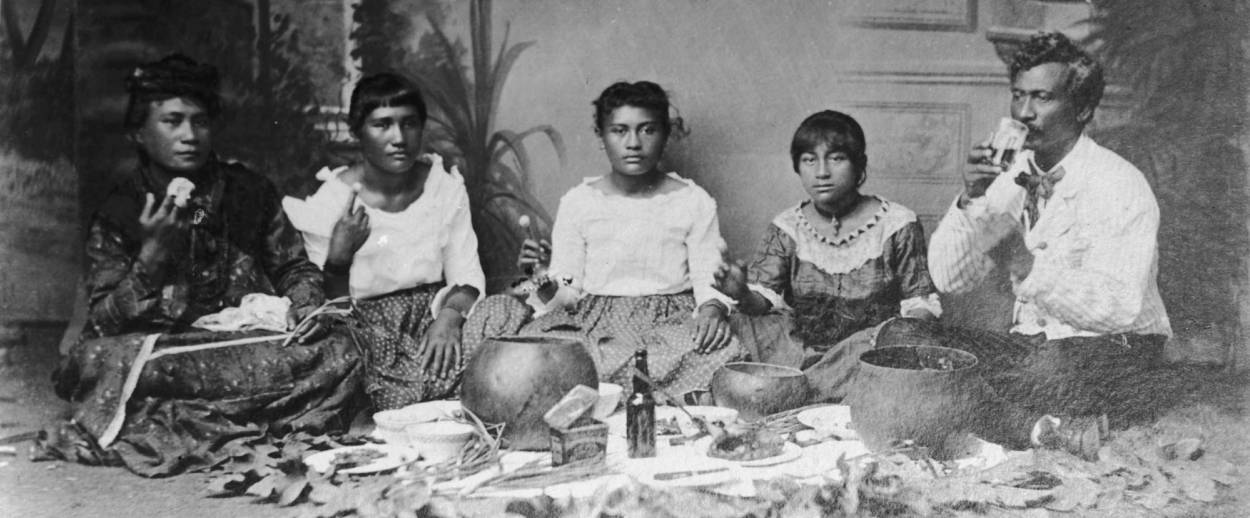

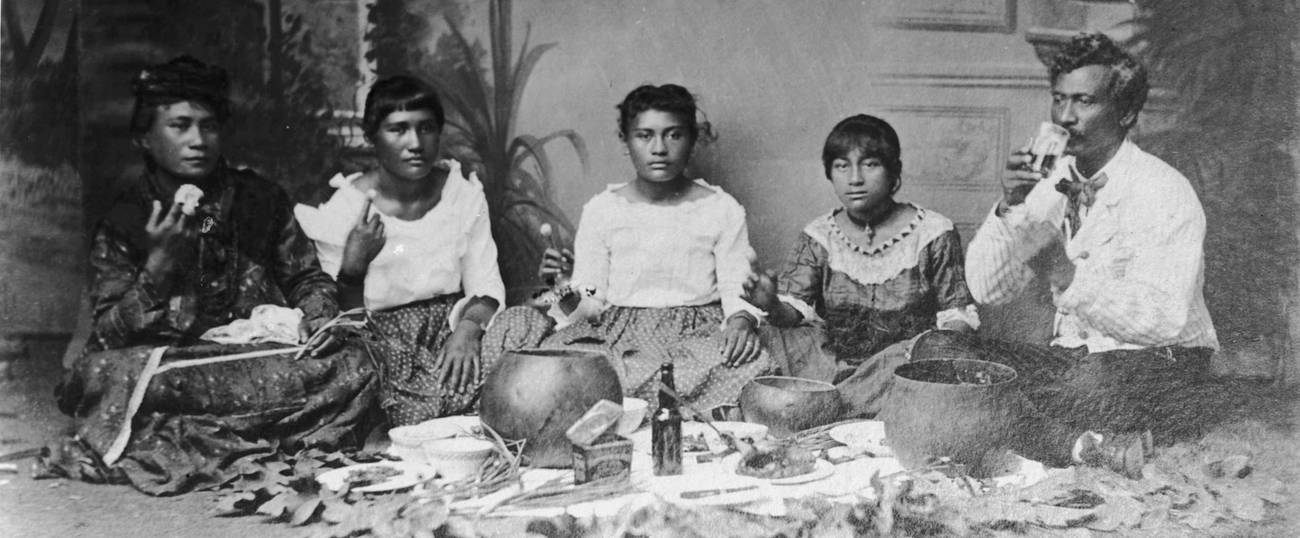

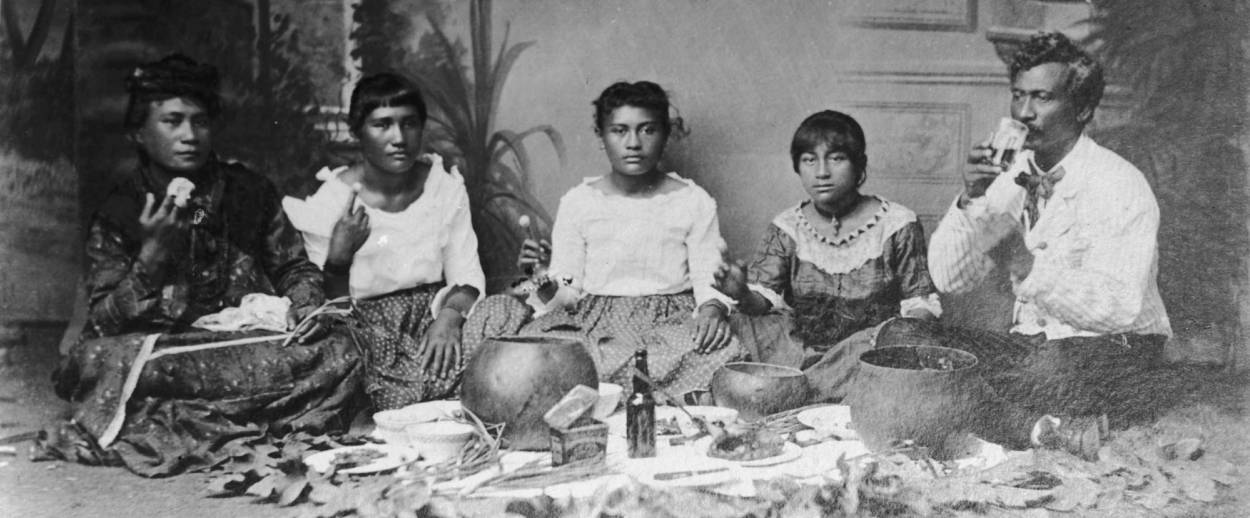

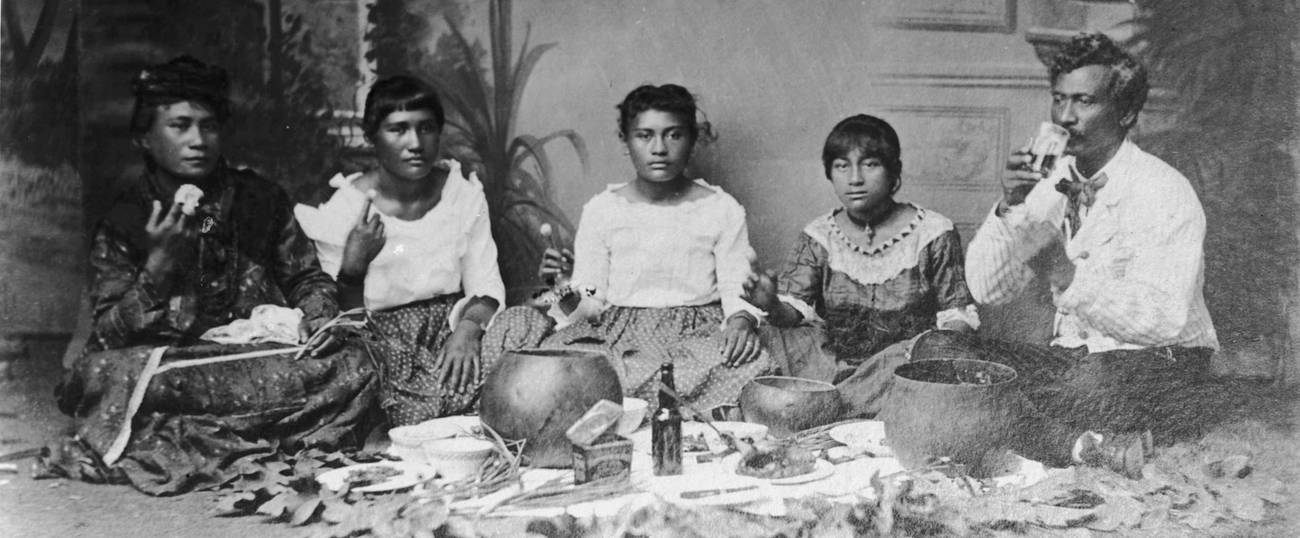

Making poi is straightforward: You boil the corm, or stem, of a taro plant in water until it is soft, then peel it, break it into pieces, and pound it on a board using a stone pounder. As you add water, the beaten taro slowly gains the consistency of a pudding. That’s poi. Some people like poi with more water, some with less. Some prefer older poi, which has fermented slightly, while others like it fresh.

Poi is the perfect food for Passover. A lot of Jews struggle to find Passover recipes that leave them feeling filled without overloading on fat or protein. That’s never a problem with poi—a little bit goes a long way. It’s also convenient. Although you could hand-pound it, most people today buy poi ready-made. As with staple starches everywhere, people have concocted different ways to serve it, but basically you simply eat it. If you are burned out after two nights of Seders, it’s incredibly convenient to know that the only thing you have to do to eat poi is open the lid and get a spoon.

There are other Hawaiian specialties I reach for regularly on Passover (I’ll name check Pau Maui Pineapple Vodka here), and grocery stores here do a good job making matzo available more or less when our lunar calendar demands. But poi is special because of the way it speaks not just to Jewish nutritional needs, but to our need to find an appropriate way to live in Diaspora in the islands.

Poi should matter to Jews because it matters to Hawaiians. Hawaiian legend tells us that Wākea, the sky, and Ho‘ohōkūkalani, whose wonderful name means something like “to cause stars to be in the sky,” had a child. That child, Hāloa, was stillborn. The first taro plant emerged from his grave. It was from their second child that humanity descended. Thus, taro is humanity’s older brother.

But taro is more than that. It is a key connection between people and the land. Working lo‘i (taro fields) is central to Hawaiian culture. Growing taro promotes sustainability. Pounding it promotes health. Eating it reaffirms identity. Today there is a widespread campaign to bring “a board in every home.” For many Hawaiians, poi is about self-sufficiency, sovereignty, sustainability, cultural identity, and an end to economic dependence.

This is why eating poi is a way of connecting with something central to life in the islands. It’s a way of asserting your Jewishness by avoiding chametz, even as you recognize your place as a Jew living in a place that has traditionally belonged to others.

How different this is from the image of American Jewry that we saw at Thanksgivukkah, the improbable cross of Thanksgiving and Hanukkah that occurred in 2013. Jews loved this holiday because of the way it merged the American experience and the Jewish experience. It told us about our place in America—no longer alien immigrants, but citizens directly connected to the founding narrative of our home country. But let’s face it: That Thanksgiving story of WASP and Native American unity glosses over the shoddy treatment the latter received—and still receive—at the hands of settlers. Thanksgivukkah was a holiday where Jews got to be American by painting over what was done to Native Americans.

More often at Passover, American Jews stress our solidarity with African Americans: The story of Passover, our holiday about social justice, has become an important part of the black religious tradition, while Martin Luther King’s words have found their way into many of our Haggadahs. But this connection is weaker in Hawai‘i, where just three percent of the population is African American. Racism works differently here as well. For instance, while African Americans are over-incarcerated in Hawai‘i as they are on the mainland, Native Hawaiians are incarcerated at even higher rates. This is just part of a long history of American colonialism that has too often handed Native Hawaiians the short end of the stick. In Hawai‘i, Jews interested in social justice must learn to respect Native Hawaiian culture, and understand Native Hawaiian experiences of oppression, even as we create a diasporic community with an authentic regional culture specific to the islands.

Hawai‘i was originally a kingdom ruled by the Kamehameha and Kalākaua dynasties, until they were illegally overthrown in 1893 by the American businessmen who controlled the sugar (and later pineapple) plantations at the heart of the islands’ economy. Hawai‘i became a territory of the United States until plantation laborers imported from Japan, China, the Philippines, and elsewhere unionized and took control of the government, leading Hawai‘i into statehood in 1959. Today the island’s ethnic breakdown reflects this history: About one-quarter of the state identifies as white, 20 percent as Hawaiian, and 37 percent as Asian. While estimates vary wildly, there are probably around 7,000 Jews in Hawai‘i today—just 0.5 percent of the population.

Hawaiian Jews have adopted several pieces of local culture: They eat malasadas on Hanukkah, have “shaloha” (shalom + aloha) for one another, take off their shoes before entering someone’s home, and eat poi. In fact, one of the dangers of eating poi for Passover is cultural appropriation. The line between respect and appropriation is a fine one. But we can find ways to connect with our Hawaiian hosts in respectful ways. I, for one, avoid dumping Hawaiian phrases into our family Haggadah, or (even worse) decorating our Haggadah with Polynesian tattoo motifs. The danger here is that Hawaiian culture becomes a party theme, and our engagement with it is superficial. This kind of thing over-eager, under-thought syncretism has the potential to cheapen both Hawaiian culture and Jewish tradition.

That’s why I like poi for Passover. It’s a Hawaiian food eaten to observe Jewish law. It’s a step toward recognizing the uniqueness of the place where I live while recognizing that I am not, in a deep sense, from that place. It’s a way of asserting my Jewish identity in a place without a lot of Jewish infrastructure. It’s how I can connect the Torah’s message of social justice with the islands’ contemporary political dilemmas.

That’s a lot to ask of a small bowl of thick purple pudding. But I think poi can do it.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Alex Golub is an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa and a member of Congregation Sof Ma’arav, the westernmost member of the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism.