The Best New Kids’ Books—About Death

A slew of new picture books will help parents explain the hardest subject of all

In the past 12 months alone, I’ve counted 14 new picture books about death—and I’m sure I missed some. Why so many? I suspect that they’re part of a trend of not whitewashing and overpolishing the world for kids.

In the past, we adults had a tendency to silence children’s uncomfortable questions, to whisk them out of the room during Yizkor services, to drop our voices when we talked of loss.

But perhaps as we’ve become more sensitized to the grieving process—and as our awareness of the persistence of terrorism, prejudice, and violence has increased—we’ve also become more inclined to talk to our offspring about our world’s unsettling, distressing qualities. Perky, shiny, all-surface picture books like The Poky Little Puppy (my own childhood favorite, which my bubbe read to me over and over) aren’t disappearing; there will always be a need for books that soothe without challenging—and not just for kids! But literature also has a responsibility to help us wrestle with the hard stuff.

Middle-grade and young-adult books in recent years have become more honest and wide-ranging, dealing with themes of loss, anger, poverty, racism, disability, and identity in ways that would have shocked my bubbe. This trend toward authenticity and openness has, I think, trickled down to picture books … and that’s a good thing.

Here’s a selection of some of the new kiddie death lit worth checking out.

I adored Ida, Always, by Caron Levis and Charles Santoso, a gorgeous story based on the lives of two polar bears at the Central Park Zoo, Gus and Ida. It’s a superb look at death and grief that holds its own as a deceptively simple story about friendship. It never names “the big park in the middle of an even bigger city” that’s home to the two ursine friends—Gus doesn’t know its name, but he wishes he could see everything outside his enclosure. Ida teaches him to listen, to feel the city’s heartbeat, to appreciate the mysteriousness. But eventually Ida starts sleeping too much, and zookeeper Sonia tells Gus that Ida’s body is beginning to stop working. She’s going to die. In language completely appropriate for a 3- to 7-year-old, with sweet yet lush and painterly illustrations, the book takes us gently through Ida’s decline and Gus’s grieving process. Gus mourns, but he also remembers what Ida always said about the city: “You don’t have to see it to feel it.” That’s true of his love for his friend, too. The book feels truthful without being brutal; I could see a child wanting to read it over and over again. It also feels very Jewish to me, for whatever that’s worth—there’s no talk of heaven, no anthropomorphized reaper, no metaphors of journeys or watchers. The only consolation for loss is memory. It’s lovely. (Age 3-7)

Always Remember, by Cece Meng, illustrated by Jago, takes a similar tack. Old Turtle swims his last swim and breathes his last breath, and his friends remember and celebrate his life. In layered, textured, brilliant blues and greens, otters trail bubbles and remember the way Old Turtle used to dive with them and make them laugh. Dolphins remember the way Old Turtle showed them glittery jewels from undersea wrecks. A starfish remembers being torn from her rock by a storm, and Old Turtle carrying her home. A manatee remembers Old Turtle untangling him from a fishing net. Old Turtle was clearly a mensch. The poetic text notes, “When he was done, the ocean took him back./But what he left behind was only the beginning.” This, too, feels Jewish—being remembered for doing mitzvot, engaging in tikkun olam, helping to create the kind of world one would want to leave behind. I can see how someone might object that these sea creatures don’t all live in the same habitats, and would not hang out and have anthropomorphized activity time, but you know, I’m good. (I was more horrified by the jacket flap copy, in which Old Turtle’s friends “lovingly remember how he impacted each and every one of them.” Argh. I can accept death, but I cannot accept this use of “impact.”) (Age 3-8)

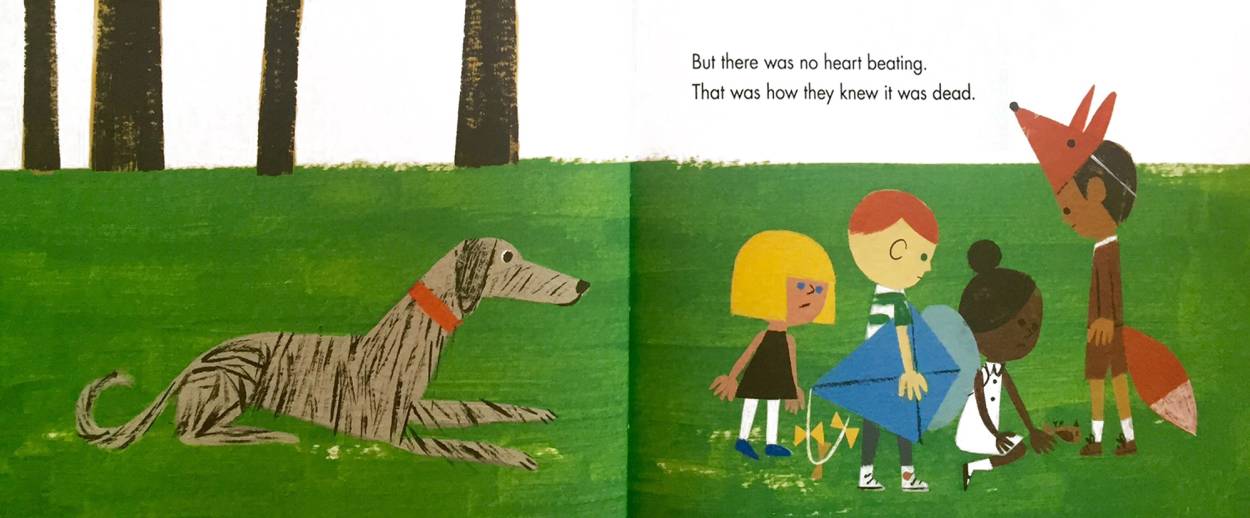

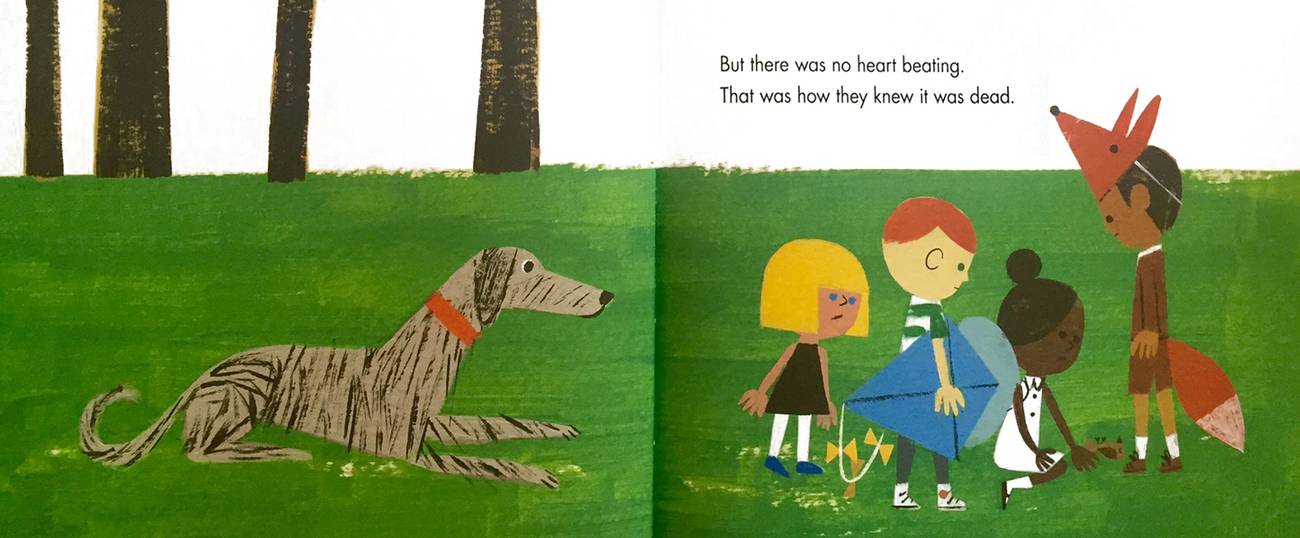

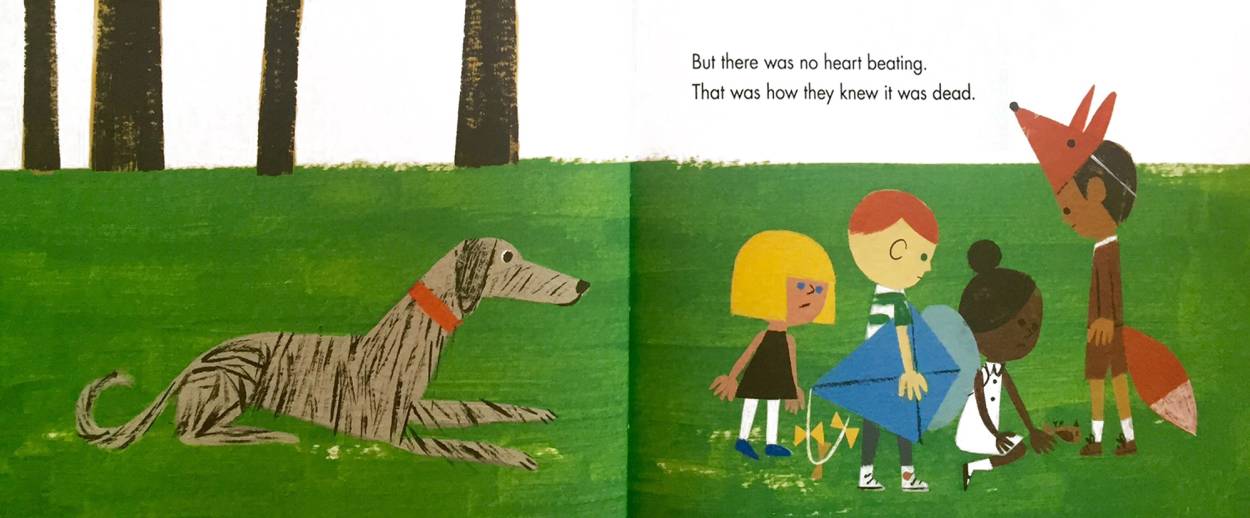

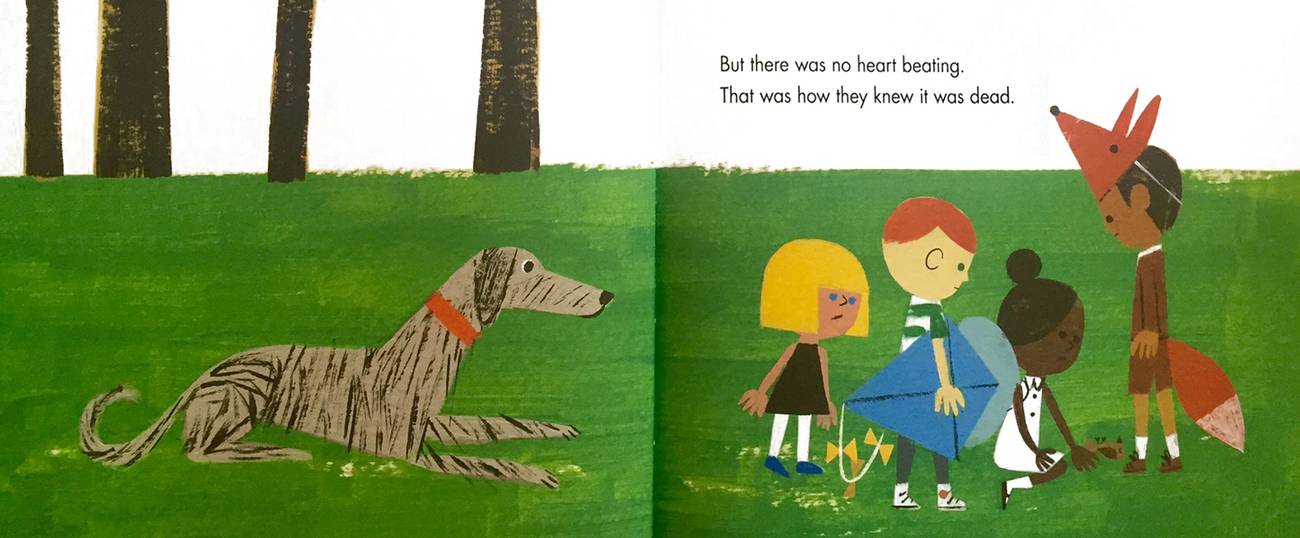

I will forever be smitten with the work of Christian Robinson. His illustrations are hip and winsome but also deep, characterized by luscious textured color and simple shapes. Now he’s illustrated a reboot of The Dead Bird, originally published by Margaret Wise Brown in 1938. His bright and sunny work is a great match for the text’s deadpan, unsentimental view of death. Unlike most children’s books published so long ago, it feels absolutely of the minute. In the story, children find a dead bird, still warm. It gradually stiffens in their hands. They’re sorry it’s dead, but glad that they can give it a funeral. They lay the bird in a hole lined with ferns and cover it with little white violets and yellow star-flowers. They sing it a song and cry for it and put up a headstone. “And every day, until they forgot, they went and sang to their little dead bird and put flowers on his grave.” This would almost be morbid, but for all the life in Robinson’s illustrations. The diverse crew of kids, one wearing a fox mask, play in a park in a city. There is green, green, so much beautiful green! You can practically smell the grass and trees. The final spread shows the kids flying kites and playing with a dog next to the little bird grave. Such a matter-of-fact approach to loss can be unnerving for grownups. (When my dad died, Josie was almost 3 and drew picture after picture of him, alternating images of him sitting at a table covered with hot dogs with images of him lying dead in a bed or in the dirt, which distressed my mom when Josie kept handing them to her.) But I love the depiction of community ritual—the need to mourn together and also laugh together. That’s what shiva is; that’s what the traditions surrounding Jewish death (shoveling dirt with the shovel upside down, laying rocks on a grave, tearing clothes, gradually allowing music and celebration back into one’s life) are about. A caveat: Parents may wish to inform children not to pick up dead things, or if they must pick up dead things, to scrub their hands afterward with the ferocity of Lady Macbeth. (Age 3-7)

For the goth elementary schooler in your life, check out Duck, Death and the Tulip by Wolf Erlbruch, a newly translated and darkly funny German (of course) book. It begins, “For a while now, Duck had a feeling.” (Of course.) Duck finds that Death is following her, and she is initially freaked out. The illustrations are beige and dark gray; Duck is an elongated Egon Schiele (but cute!) creation; Death has an actual skull head (but cute!) and a long beige-and-gray-checked gown. For a while, Death just hangs around, and he and Duck become almost friends. Duck asks what will happen to her, and Death does not answer. “Some ducks say you become and angel and sit on a cloud,” she hints. “Some ducks say that deep in the earth there’s a place where you’ll be roasted if you haven’t been good.” Death answers only, “You ducks come up with some amazing stories, but who knows?” One comforting(ish) thing that Death says is: “When you’re dead, the pond will be gone, too—at least for you.” Too existential? Not for me. Picture books are a conversation; this is a good opening for talking about how we don’t know what happens after death—again, very Jewish. (Also, I appreciate the brave decision not to use an Oxford comma in the title.) (Age 6-9)

Cry Heart, But Never Break by Glenn Ringtved, illustrated by Charlotte Pardi, offers up another anthropomorphized Death—this one sallow, black-cloaked, and with an Ingmar Bergman realness. In gentle, very European, wavery-lined acrylic illustration gentled with washes of watercolor, four children try to protect their very ill grandmother from Death, who is sitting in their kitchen. But after chatting with him, they come to understand that death is inevitable … and also a way to find meaning in existence. “What would life be worth if there were not death?” Death asks them. “Who would enjoy the sun if it never rained? Who would yearn for day if there were no night?” For me, this book was perhaps too literal—when a goofy duck copes with the actual figure of death, it seems more fairy-tale-ish than when human children do. But I loved the final lines: “Ever after, whenever the children opened a window, they would think of their grandmother. And when the breeze caressed their faces, they could feel her touch.” The last spread is lovely, showing a boy looking out an open window framed by billowing curtains, while a shadow behind him, unseen, shows the silhouette of the grandmother looking fondly down at him, her hand on his shoulder. (Age 6-9)

Death Is Stupid, by Anastasia Higginbotham, is the book I’d give to a kid who is grieving and angry. It’s as much a workbook as a story, didactic but potentially very helpful. With a deliberately childlike mixed-media approach, Higginbotham (whom I know slightly from the early ’90s, when she was at Ms. magazine and I was at Sassy, right next door) uses photographs, bubble letters, handwriting that looks done in Magic Marker, and shadowbox-esque cutouts laid out on brown-paper-bag backgrounds to tell the story of a kid coping with his grandmother’s death. He’s (rightly) furious at platitudes like “she’s in a better place,” “now she can rest,” and “be grateful for the time you had with her.” He’s upset by his dad’s loud sobbing. But in the end, the boy and his father (who appear to be people of color) come together by tending Gramma’s garden and making her famous tomato sauce. An “activities” section in the back encourages kids to feel close to the one they lost by wearing something they wore, playing the games they liked, reading the books they read. There’s a place to glue a picture of your loved one, surrounded by shiny collages, sequins, and little inked hearts colored in with red pencil. Pro tip for Jews: We see an ornate coffin, and an image of the boy lighting candles in front of a stained-glass panel—neither of which are Jewish elements of funerals—but these images provide an opportunity to talk about different people’s traditions. (Age 6-11)

Similarly, The Goodbye Book by Todd Parr is probably best for a very young child who’s lost a friend, family member, or pet. It’s appropriate for kids as young as 2, since even tiny kids are familiar with Parr’s primary-colored, supersimple work and ultra-basic sentence structure. At first we see two goldfish in a bowl. But then there is only one. Through the goldfish’s confusion, we learn that “you might not know what to feel” when a loved one dies. “You might be very sad. You might be very mad. You might not feel like talking to anyone.” The goldfish thinks about the good times it had with its fishy friend, and the text says, “You’ll have days when you feel up and days when you feel down.” It concludes, in a way that’s perfect for very small kids who fear abandonment, “And you’ll remember that there will always be someone to love you and hold you tight.” A boy holds the goldfish’s bowl, surrounded by hearts. (Age 2-6)

And finally, the one book I can’t recommend, despite its fabulous art: Grandad’s Island by London-based author-illustrator Benji Davies. Syd visits his grandfather in an appealingly ramshackle home in a line of row houses in what looks like a British seaside town. Grandad shows him a mysterious steel door behind a drape in the attic. The door opens onto the deck of a ship, and suddenly the two are traveling to a wild and beautiful island. The colors are crazy-intense; the illustration style feels very Best Animated Short (not an insult). Syd helps his grandad fix up a little thatched-roof shack, while an orange ape delivers a tray of tea and delightful tropical beverages in coconuts. They swim and paint, and when it comes time to leave the island, Grandad says “You see … I’m thinking of staying.” “Oh,” said Syd. “But won’t you be lonely?” Wait, what? Kids don’t ask that. Their first question is “What about me?” Grandad says no, he won’t be lonely. He’s surrounded by psychedelic wildlife; the ape has set up a little lounge chair and a vase next to the tea and there’s a hammock and everything. Syd navigates the ship home alone (yeah, no fears of abandonment here) and goes back to Grandad’s the next day; now the big metal door in the attic is gone. Look, I’m fine with metaphors for death, but in this case the person has just chosen to leave you and live somewhere better! How is that helpful to a child? And wait! Spoiler alert! It gets worse! A tropical bird flies to the attic window with a message for Syd: a picture of Grandad and his animal pals. Great, the book has just conveyed that death isn’t really death, that our loved ones can send mail from the great beyond. I don’t think I am being too literal now: Death is final. And it sucks. And it’s very hard for little kids to understand that. This book would make it harder. Pass.

There are still more death books coming this fall, including one by Julia Alvarez of the beautiful How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents, illustrated with woodcuts. I haven’t seen it yet. But I’m feeling hopeful, and upbeat about this kid-lit trend in general … which is, admittedly, a funny thing to say about death.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.