An Air Force Chaplain’s Unforgettable Passover, 50 Years Ago

How a week of military leave created one rabbi’s unlikely connections to Menachem Begin and Ted Kennedy, on the eve of the Six-Day War

For Rabbi Barry Dov Schwartz, April 1967 was filled with anticipation.

Between running services at the synagogue he founded on Westover Air Reserve Base, Massachusetts, he conscientiously checked his mailbox for the inevitable Temporary Duty Order, which would advise where he’d be spending the upcoming holiday. The prior year’s order appeared only six days before Passover—along with a winter parka, because he was being sent to run the Seder at Goose Bay Air Force Base in northern Canada. Schwartz wound up asking “What Makes This Night Different?” before hundreds of soldiers and military brass in a frozen wasteland where the lone Jewish civilians were the mayor of nearby Happy Valley and his daughter.

In 1967, Schwartz was still hoping for the best (Hawaii) but prepared for the worst (Vietnam). What he did not expect was to receive no orders at all—but that’s precisely what happened: After nearly two years of service and a promotion to first lieutenant, Schwartz would be on leave for a Jewish holiday.

Though home-cooked matzo brei would be waiting less than two hours away in Brookline, Schwartz instead contacted Lt. Col. Rabbi Mordechai Piron, deputy chaplain of the Israel Defense Forces, whom Schwartz had met at a chaplain’s conference a few months earlier in Lakewood, New Jersey. At that conference, Piron had extended an invitation (whether in passing or otherwise) to visit with him in Israel “anytime.” Certainly, thought Schwartz, Passover was “anytime.” The response from Piron was warm and enthusiastic; after all, Schwartz was a decorated officer serving in the military of Israel’s most essential ally. Within a few days, accommodation arrangements were made and Schwartz was scheduled to be Piron’s guest at a massive public Seder for Israeli soldiers. Schwartz would later tell his congregants in Westover that, though he was sorry to leave them, he was honored and thrilled to spend Passover with “modern-day Maccabees.”

All that remained was getting to Israel on time. It was April 19, and the Seder was less than five days away. Schwartz checked the base’s outbound-flight log for the day and found a KC-135 Stratotanker leaving for Terrajon Air Force Base in Spain. Without determining the balance of his travel itinerary—but figuring it couldn’t hurt to get halfway to Israel—Schwartz hopped aboard.

Despite the tight schedule, once he arrived in Spain, the chaplain was unable to restrain his overarching life objective: connecting with fellow Jews. He was soon put in contact with Capt. Marshal Cohen, the lay leader of the Jewish community on Terrajon Base. Schwartz would record their initial conversation in a May 1967 memo to his Westover community titled Passover Postscript:

Schwartz: Capt. Cohen, this is Rabbi Schwartz from Westover, and I’m just passing through, and…

Cohen: CHAPLAIN Schwartz!? How wonderful! We knew you’d come! We have a Seder for 200 people and no rabbi. We were sure God would send someone.

Schwartz: But, but, you don’t understand, I’m only…

Cohen: Wonderful, don’t move. I’ll be right down and pick you up at the passenger terminal. Shalom!

“I tried,” Schwartz told me recently, from his home in North Woodmere, New York. “After a while—he kept on persisting—I realized I couldn’t leave a congregation like that, a community that needs a rabbi, for many reasons. One reason, I remember, they were having a lot of non-Jews. Maybe that’s where I got my concept of always having non-Jews at my Seder. The Seder on base, it’s an official event, all look forward to it, very fancy, you dress formally, and the food was delicious. Although Cohen and others were intelligent Jews, they weren’t well-versed to conduct a Seder. The message would be mixed. And I didn’t want non-Jews to have a bad impression.”

Schwartz reported the event in his Passover Postscript:

So—a funny thing happened on the way to Israel. I never got there for the Seder. I “volunteered” to remain at Terrajon. The truth is, I was so impressed with Capt. Cohen and his colleagues and their devotion to Jewish observances, I felt it an honor to be in their midst. How inspiring it was to see these young men so concerned about Judaism. Indeed, a heart-warming experience for a rabbi!

“I always try to make a Seder lively and relevant,” Schwartz told me. “In Terrajon, I was on a microphone because it was a huge room and I wanted to be heard. I gave out parts, as if at home. I canvassed the crowd in advance to see if anyone could read Hebrew.”

Schwartz described the Seder itself as “beautiful,” including tourists, exchange students from the University of Madrid, local Spanish Jews, and even two military servicemen who recognized the chaplain from Passover 1966 when they were stationed at Goose Bay. Even though he didn’t make it to the Seder in Israel, Schwartz raised his four cups of wine that night with an overwhelming sense of appreciation and clarity, realizing that he was exactly where he was meant to be.

***

Over the next 50 years, Schwartz would lead Conservative synagogues in Perth Amboy, New Jersey, and Rockville Centre, New York. And he became “personal rabbi” to numerous politicians, priests, and even a movie star. Staunch halachic integrity, open-mindedness, and heaping doses of mazal have keyed Schwartz’s unprecedented access to and revered status in Long Island’s Catholic community and local government.

Seven years after he retired as a congregational rabbi, Schwartz—now 76—is still active as police chaplain in Nassau County, and the longest-serving board member of the very Catholic Mercy Medical Center. He continues to focus on supporting Israel through his strong political connections in New York and building bridges between the Jewish and non-Jewish community. He is still close with Bishop William Murphy of Rockville Centre, who himself recently retired.

The lessons Schwartz learned at the 1967 Seder in Spain remain with him today: “I know some Jews won’t have non-Jews at their Seder, but I make it a point,” said Schwartz, whose Seders have included such guests as Bishop Murphy; Nassau County’s then-police, chief Steven Skrynecki; and former New York Sen. Dean Skelos. “I think this comes from my experiences in the military—the necessary interaction and the value of understanding one another.”

***

“I didn’t know I wanted to be a rabbi,” Schwartz told me with his signature wit, “until I turned 6. And the urge—I am not saying I am a prophet—but the urge came from my stomach, like it says in Jeremiah.”

While other boys his age played in the streets and parks of 1940s Boston, he was at home practicing sermons. His father was a trained cantor, whom Schwartz credits as a lamed-vavnik and one of his two great role models. The other larger-than-life figure he emulated was Rabbi Joe Shubow, known as “The Fighting Rabbi” because of his bombastic style and propensity to pound the pulpit of Schwartz’s Conservative synagogue in Brighton. Growing up, Schwartz was called the “little man” by his neighbors because he attended synagogue so consistently—and because he wore a fashionable hat before his 9th birthday. When adolescence ended, Schwartz moved to New York after being accepted to the Jewish Theological Seminary, where he studied under such luminaries of Conservative Jewish thought and Torah scholarship as Abraham Joshua Heschel, Saul Lieberman, and Robert Gordis.

As the recipient of the Cyrus Adler Award for outstanding JTS graduate in 1965, Schwartz needed only to choose which large and prosperous community suited him. Then Vice Chancellor David Kogan came into the classroom, with an announcement:

As clergy, you cannot be drafted into the military. Chaplains must volunteer. As representatives of JTS, we feel it is very important you serve and we will not be placing anyone in a community synagogue who does not volunteer. So … Army, Navy, or Air Force?

In lieu of his trusted compass, Schwartz called his mother. You look good in blue, she told him. Join the Air Force. And so Schwartz took the first of many unexpected detours and headed off to basic training that summer.

***

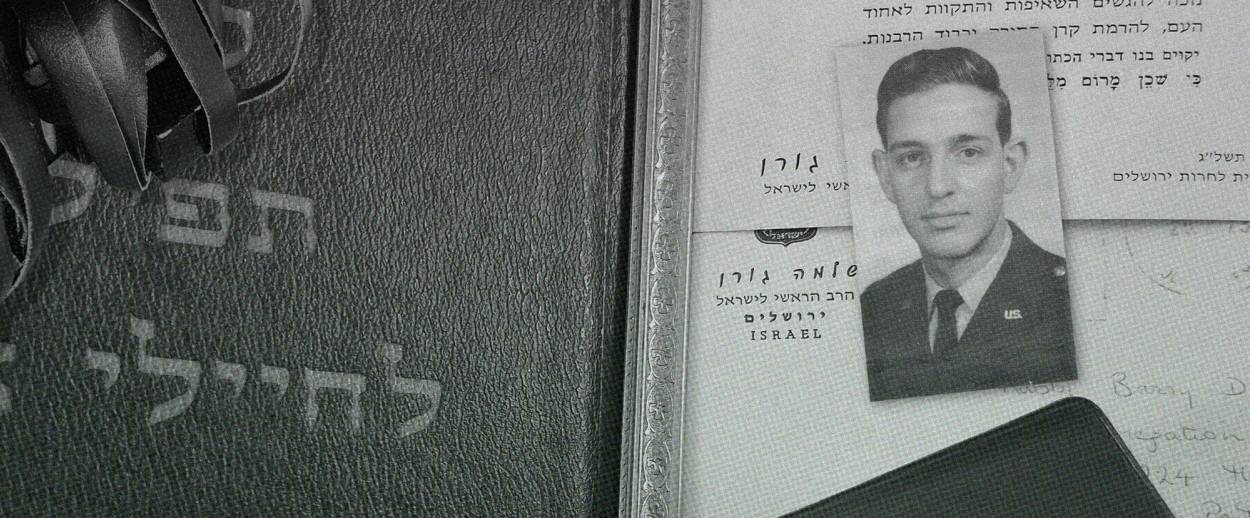

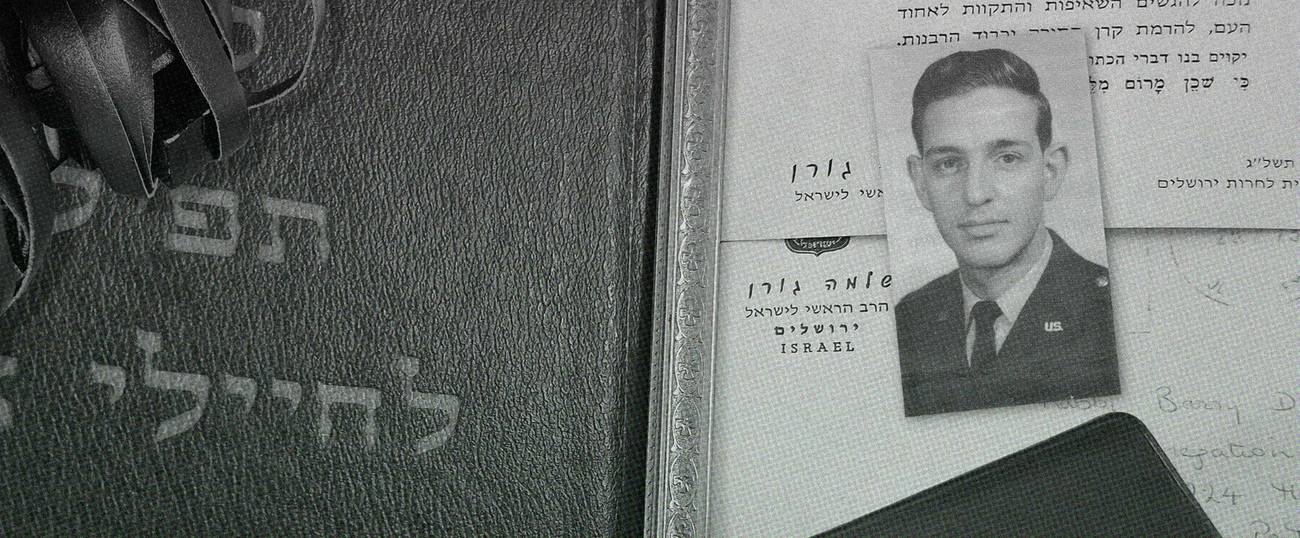

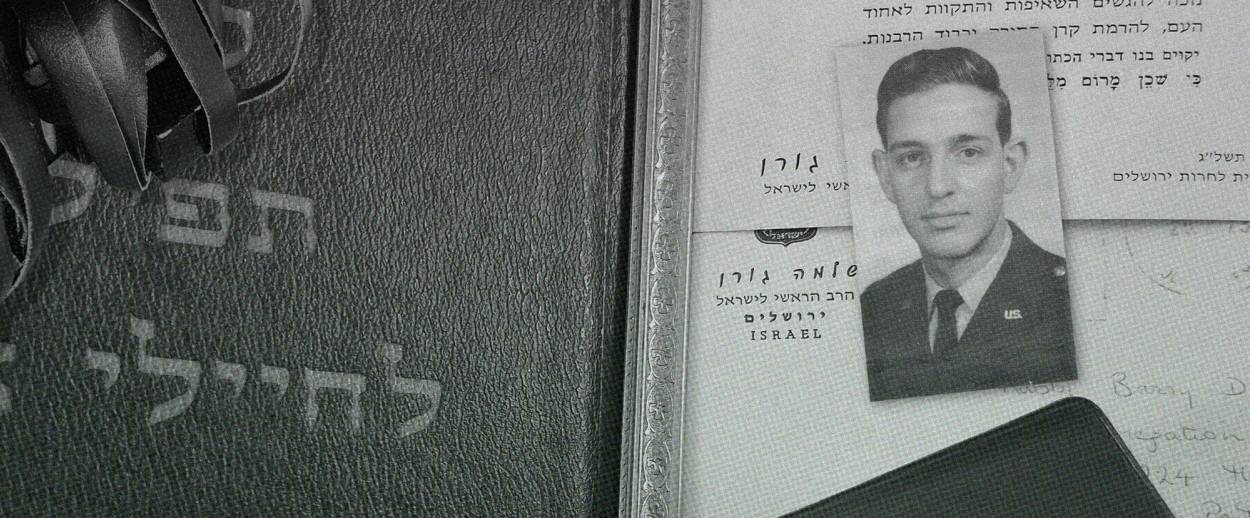

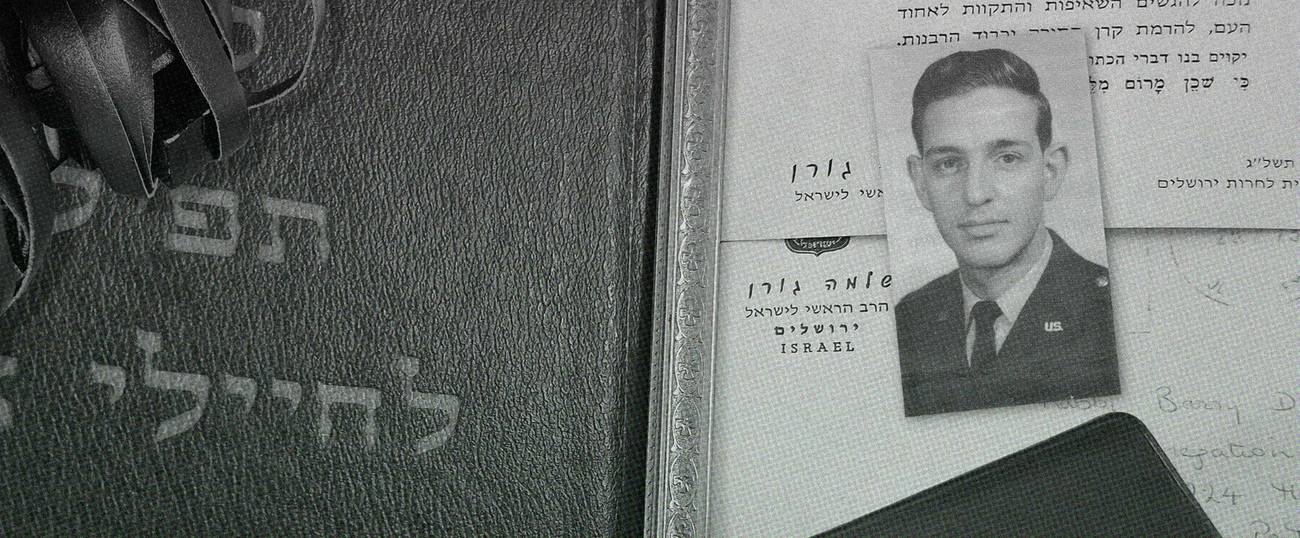

Schwartz did finally make it to Israel for the second half of Passover in 1967, as soon as he was finished with his Seder duties in Spain. He was welcomed at Lod Airport in Tel Aviv on the second day of chol hamoed by representatives of General Rabbi Shlomo Goren, chief rabbi of the IDF. To his dismay—at first—Schwartz was taken to what felt like the small attic of the Savoy Hotel and shown a bed. Later, he would learn that this was the famed “Room 17,” where Menachem Begin hid during the British occupation and the Irgun made plans to liberate Israel; to be quartered there was the highest honor. Schwartz spent Shabbat chol hamoed with Goren and his family—the same rabbi who would be blowing a shofar at the liberated Western Wall only one month later.

Before he returned to America, Schwartz was escorted as a guest of Piron and Goren to the ceremony swearing in the newest units of Israeli soldiers. “During that trip, I heard the tanks rumbling throughout the land,” Schwartz recalled. “Always the sound of tanks. You could sense that something was about to happen. There was a noticeable dread in the air.” At the ceremony, Schwartz was given a package including a siddur, a pair of tefillin, and an inscribed Tanakh—the same items given to Israeli soldiers at the time.

“I knew I would keep them forever,” Schwartz said. “And close to me forever, which I did.” He still dons those tefillin.

His first day back at Westover, Schwartz sent two letters: one to Piron, expressing gratitude for the experience (along with a check for $18), and one to Sen. Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts, encouraging solidarity with Israel.

On June 5, 1967—the first day of the Six-Day War—Kennedy wrote back to Schwartz personally:

The next few days will be crucial for the Middle East, and, indeed, for the whole world. I assure you of my concern and deep personal commitment to the continued existence of a free and independent Israel.

“The American non-Jewish soldiers loved Israel,” Schwartz recalled. “They loved the bravado that the country showed. I never bumped into any anti-Israel statement or sentiment in the military. Anti-Jewish, yes. Not anti-Israel. I remember the expression they used about Israel: Kick ass, they used to say. I was embarrassed by that phrase, but they wanted Israel to do that.”

In one of his earliest examples of bridge-building, the soldiers at Westover—both Jew and non-Jew—came together to joke that Schwartz, their affable chaplain, had been in Israel for only one week and managed to start a war.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Jordan Hiller wrote film reviews for 10 years at Bangitout.com and is author of an almost published novel, The Midnight Ride of Solomon Engle.