Turning Religion Into a Theme Park

While Bible-themed venues have proved popular with American—mostly Christian—tourists, Israel’s Shtetl Museum had trouble getting off the ground

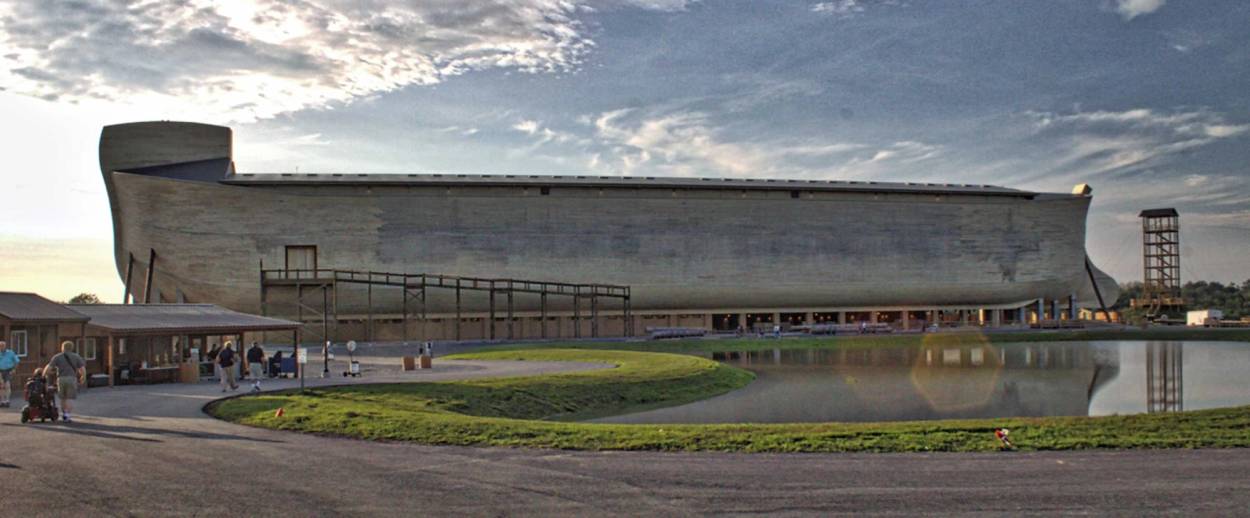

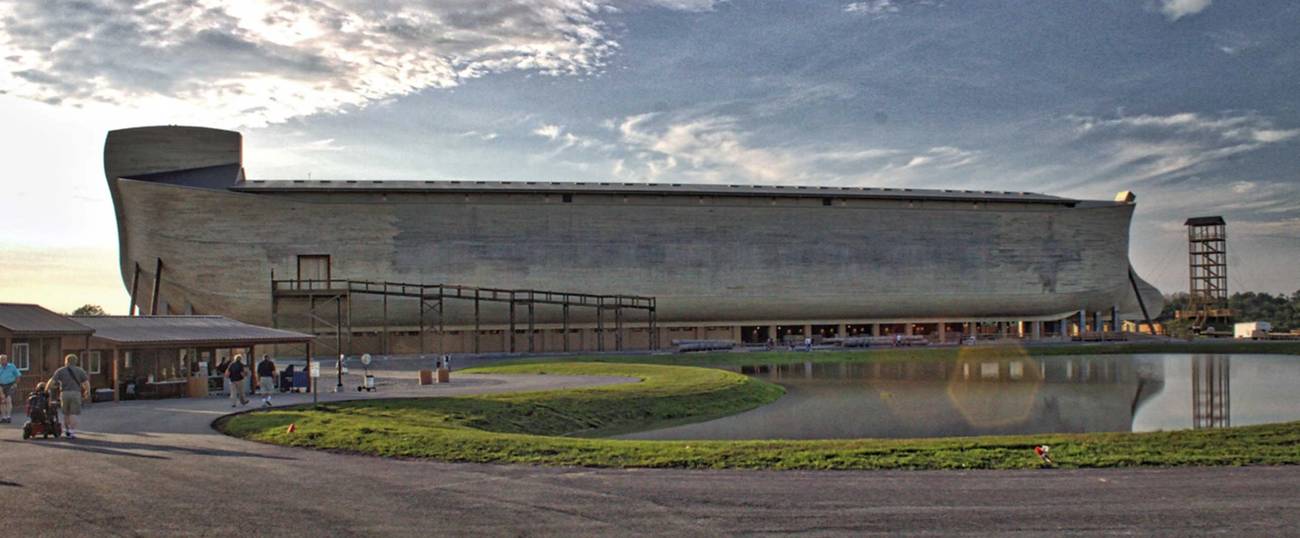

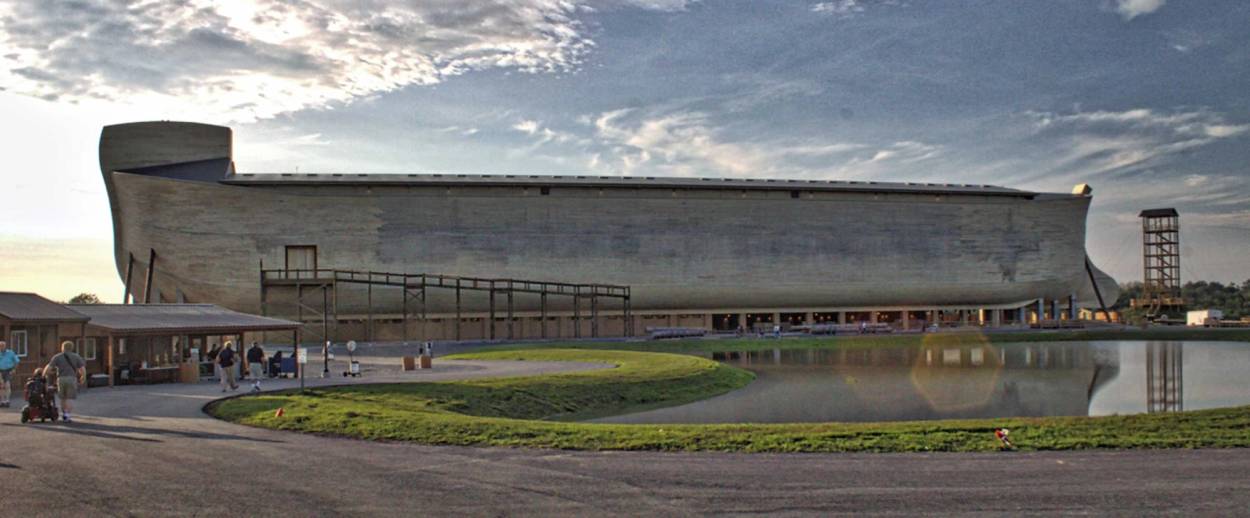

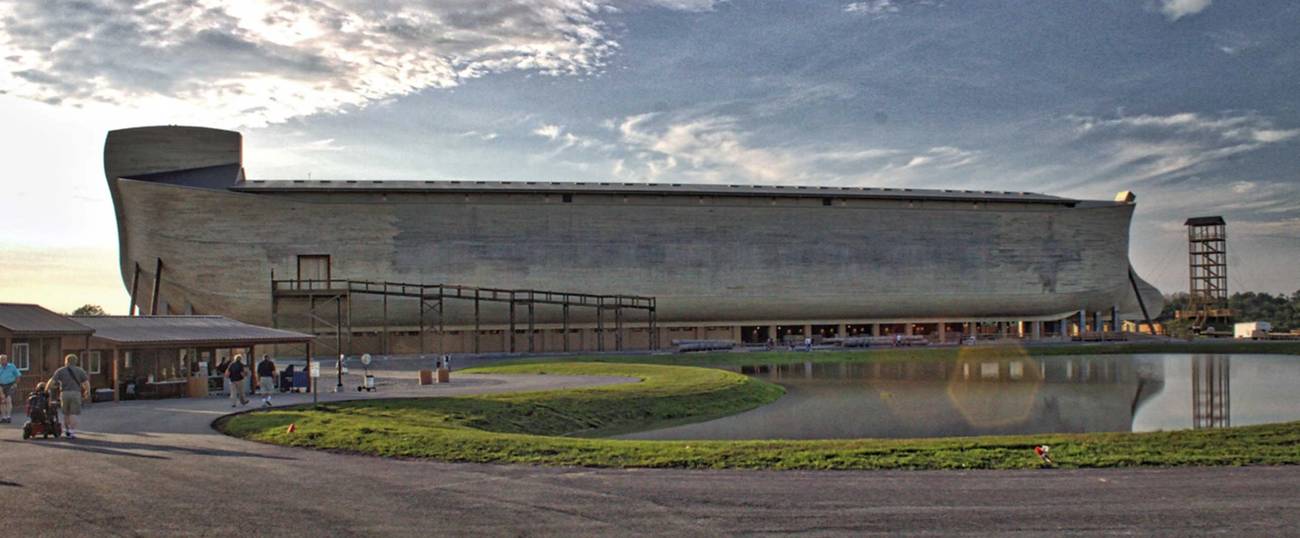

Are you looking for something to do with the kids on a summer afternoon? If you lived in northern Kentucky, you could make a beeline for Noah’s Ark, which recently washed up in the Bluegrass State. A football-field-and-a-half in length and a striking five stories tall, this latest iteration of the fabled wooden boat is breathtaking, or, as its promoters would have it, “mind-blowing.”

If a biblical nautical adventure doesn’t suit your fancy or pocketbook (adults pay a whopping $40 admission fee), how about the Holy Land Experience in Orlando, Florida? You could easily while away an entire weekend at this “living biblical history museum,” taking in Herod’s Temple and the Qumran caves; poring over facsimiles of ancient texts in the Scriptorium; encountering a laser show in which the Ten Commandments are etched in fire; seeking refuge from the crowds in the Oasis Palm Café; or shopping for souvenirs in the old Scroll Shop.

For all their razzle-dazzle, these two sites stand on the shoulders of and take their cue from earlier generations of biblically inspired attractions, from Palestine Park in upstate New York to Fields of the Wood in North Carolina.

Situated on the shores of Lake Chautauqua, Palestine Park was established in the late 19th century to heighten visitors’ relationship to the Bible. Dotted with miniature plaster models of Jerusalem and other cities mentioned in the Old and New Testaments, the park’s contours echoed the topography of the promised land. Strolling the grounds of Palestine Park, it was said, was “almost equivalent to an actual tour of the Holy Land.”

Much farther south, several miles outside the town of Murphy, North Carolina, lies what many believe to be the world’s largest Ten Commandments. Since the 1940s, concrete letters, each measuring a whopping 5 feet tall and 4 feet wide, spell out every word of the ancient text in English. Nestled in a grassy slope, they beckon visitors, challenging them to climb 350 steps to reach the top. Fields of the Wood renders the Ten Commandments an exercise in both spiritual faith and physical stamina.

Then, as now, the audiences for these exemplars of religious tourism didn’t seem to find it the least bit odd or in any way disjunctive that Lake Chautauqua stood in for the Mediterranean or that Noah’s Ark came to rest in the American heartland. Immersive environments all, these latter-day biblical redoubts aligned literalness with scale. Whatever doubts one might have brought along for the ride were dispelled, or, better yet, subsumed, by the spectacular nature of the experience.

***

Religious theme parks such as Noah’s Ark and the Holy Land Experience draw hefty crowds, but American Jews are usually not among them. Perhaps they’re too keenly aware of the Christological agenda that subtly but unmistakably fuels these ventures—or, in the case of Noah’s Ark, of its sponsor’s commitment to creationism—and stay far, far away. I suspect, too, that something in the cultural makeup of America’s Jews—a kind of built-in skepticism, a penchant for eye-rolling—presupposes them to be wary of extravagantly scaled historical fabrications, whose recherché appeal eludes them.

How else, then, to account for the absence of a Jewish version of the Holy Land Experience or of a Jewish counterpart to Plimoth Plantation and Colonial Williamsburg? Yes, the American Jewish landscape abounds in museums (that’s another story), but outdoor Jewish living-history facilities, equal parts amusement park and heritage site, are nowhere to be found in the United States, at least not in real life.

Where they do exist is on the printed page: In Dara Horn’s short story, Shtetl World, the protagonist, Leah, a graduate student in Yiddish literature, earns her keep during the summer working in an unnamed ersatz shtetl situated in a woody area of western Massachusetts. Clad in a “woolen ankle-length skirt, long sleeves and enormous plastic-pearl-brocaded headscarf,” she presides over a dry-goods store where the overture to Fiddler on the Roof is piped in continuously. In the absence of much foot traffic, Leah contemplates her fellow citizens: a milkman, a crippled beggar, a fiddler on the roof, a bride and her groom, and Mendel the bookseller who, every afternoon at 4:30, doubles as a pogromchik. Leah doesn’t take kindly to any of them, but what “really bothered her was that there were rides.”

Horn might have drawn inspiration for her sly take-down from Israel’s Shtetl Museum, a project that has been in the works for more than a decade but has yet to be realized—and probably never will be. I don’t believe any provision was made in the plans for rides, but just about every other feature of East European small town life of the early 20th century has been accounted for: a yeshiva and a shul, a market square, and a mikveh. Why, there’s even a castle, home to the local nobleman.

The inspiration of Brooklyn College professor and Holocaust scholar Yaffa Eliach, the Shtetl Museum was intended as an “open-air museum of East-European Jewish history and culture in the form of a life-size shtetl.” More simply put, the site aspired to be a “Jewish Williamsburg.” (No, not the one in Brooklyn.)

Collapsing time and space—a Lithuanian village in contemporary Rishon Le-Zion?!—the Shtetl Museum hoped both to recreate the town of Eyshishok, from which Eliach hailed, and to represent the shtetl as a quintessential Jewish phenomenon. Much like the folk villages that populated World’s Fairs in the late 19th and early 20th centuries—but better—it was designed to underscore, and celebrate, the vitality of prewar Jewish life.

The conceit behind the Shtetl Museum was for visitors not just to observe the goings-on, but to throw themselves wholeheartedly into the experience: shopping in the market square, taking a dunk in the mikveh, seeking out the sage counsel of the shtetl rabbi, and celebrating a bar or bat mitzvah on the premises. The Shtetl Museum planned to take the notions of virtuality and reproducibility, the underpinning of living-history museums everywhere, and run with them. (See Jeffrey Shandler’s essay “The Shtetl Subjunctive,” in Culture Front .)

Since it broke ground in 2003, the project has raised several million dollars in funding and generated considerable public and scholarly interest, but since then, and most especially in the wake of Eliach’s prolonged illness and subsequent death in 2016, it stalled and then came to a halt. Did the Shtetl Museum set its sights too high? Founder on the shoals of politics? Cost too much? It might have, but the proximate cause of its abbreviated shelf life had more to do with the cruelties of fate than with any of these factors. The viability of the Shtetl Museum rested entirely with Yaffa Eliach, and when her health declined, so, too, did its prospects.

These days, the only feature of the Shtetl Museum that remains alive is its website, which is independently maintained and, more curiously still, written in Thai.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Jenna Weissman Joselit, the Charles E. Smith Professor of Judaic Studies & Professor of History at the George Washington University, is currently at work on a biography of Mordecai M. Kaplan.