A Forgotten Gay Jewish Pioneer Rises Again

Activist Leo Skir wove together his identities in a groundbreaking essay more than 50 years ago

In the course of my research into LGBTQ Jewish history last year, I came across an essay titled “The Homosexual Ghetto,” published in 1965 in The Ladder, the magazine of the influential lesbian organization The Daughters of Bilitis. My research is part of a project to compile the first comprehensive anthology of LGBTQ Jewish history, with more than 100 primary texts ranging from late antiquity until 1969. While some of the sources might have been familiar and expected, others—like this essay—were a complete surprise.

The author draws on his background in the Zionist movement, and his experience as a first-generation American Jew, to call for solidarity among homosexuals, linking the fight for gay rights as part of the larger national and global struggle of oppressed minorities: “This essay is not written for those who have surrendered to fear, but for the others, the fighters. I think we need to constantly reaffirm our perspective in the fight for homophile rights, to realize that we are part of a broad, general movement towards a better, freer, happier world.” The author castigates his fellow homosexuals for holding themselves back in a self-declared “ghetto,” declaring that “the homophile movement is needed, as Isreal [sic] is needed, at this point in history,” and urges the readers to join him in fighting for full integration and equality.

While religion was a popular topic in gay and lesbian magazines in the 1950s and ’60s, it was almost always Christianity being discussed, and usually with negative implications. To see a self-proclaimed gay writer engaging explicitly and thoughtfully with Judaism, and declaring both Judaism and homosexuality to be central to his sense of self, was unprecedented. From this article, I began to understand that even in the early days of the Gay Liberation movement, there were people for whom religion—and Judaism specifically—was not just an obstacle to overcome, but a constitutive element of their identity.

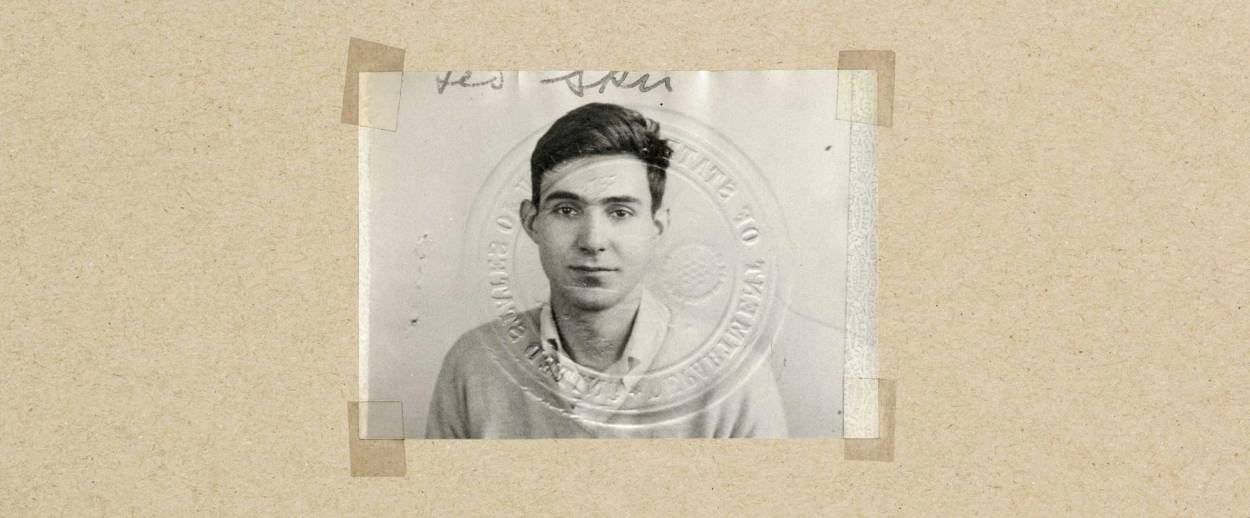

The article was attributed to “Leo Ebreo,” i.e. “Leo the Jew,” which I was certain was a pseudonym; sure enough, some weeks later, flipping through other issues of The Ladder, I came across another article with a similar theme, this time giving the author’s real name: Leo Skir, who “has appeared in The Ladder in the past as ‘Leo Ebreo.’”

Leo Joshua Skir was born in Brooklyn on May 10, 1932 (named, presumably, for his paternal grandfather, Louis Skir, a Russian-born rabbi who had died three years earlier). His father, Isaac Skir, had immigrated to the United States as a child in 1910, and gone on to study medicine; his mother, Jane Langer, was born in New York to Galician Jewish parents. Young Leo received his Jewish education at Shaare Zedek and the Brooklyn Jewish Center; in a 1971 interview with the Indiana-based newspaper The Jewish Post and Opinion, Leo recalled his home as “a Socialist political family environment whose family consider themselves Conservative Jews.”

In his teenage years, Skir joined the Zionist youth movement HeHalutz, and in 1949 spent the summer as a counselor at the movement’s havvat hakhshara, or “training farm,” in Poughkeepsie. There he met Elise Cowen, a Beat poet who would become a lifelong friend. Through Cowen, Skir befriended another iconoclastic Jewish Beat poet: Allen Ginsberg, who remained close to both Skir and Cowen for the rest of their lives. Cowen committed suicide in 1962; after her death, Leo Skir preserved the binder of her typewritten poetry that has allowed her work to become more widely known today. In what is believed to be her last poem, Cowen bids a sad farewell to her small circle of family and friends; to Skir, she writes: “Leo—Open the windows and Shalom.”

***

I was surprised to learn that Skir, who died in 2014, had lived in the Twin Cities—my current home. I immediately wondered whether he had left any trace here, but his papers had apparently disappeared; numerous inquiries to LGBTQ archivists, historians, and community activists turned up nothing. I began to worry that the records of his life—letters, drafts, manuscripts, clippings—had been lost or discarded.

This is so often the fate of the historical documentation of marginalized communities, including LGBTQ people. At the University of Minnesota, I have been working with the Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection in Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Studies, which is one of a small number of dedicated LGBTQ archives in the United States. Housing thousands of feet of material in dozens of languages, the collection includes periodicals and newspapers, pulp fiction, political pamphlets, personal papers, and the organizational records of everything from the Log Cabin Republicans to the Lesbian Feminist Organizing Committee. The existence of the Tretter Collection does not just mean the preservation of LGBTQ history; it also provides a space for scholars, activists, and community members to grapple with the past and all the challenges that it presents. I knew that if I was able to locate anything of Skir’s, the Tretter Collection would be the right place for it.

Cowen turned out to be the key to finding Skir. A professor who published a contemporary edition of her poems remembered interviewing Skir at his nursing home in Saint Paul. The nursing home was able to put me in touch with a social worker who had Skir’s case files, and she promised to pass my information on to the primary contact who had dealt with Skir’s estate after his death.

Shortly afterward, I got a call at my desk in the History Department at the University of Minnesota from this contact: one of Skir’s college friends, who had moved to the Twin Cities in 1964 to work at the university (Skir had followed him here in 1975). A month later, I found myself driving with the curator of the Tretter Collection to meet him in a quiet suburb of Saint Paul.

Now a retired professor emeritus, he was not only generous in sharing his memories of Skir but also happy to donate the seven boxes of Skir’s personal papers in his garage to the university; the Tretter Collection, in turn, was happy to expand its archive. Loading the boxes into the car, I thought of the strange circles of coincidence that had brought the quest for Leo Skir right back to my own backyard. In his 1965 article in The Ladder, Skir had ended with an allusion to the book of Matthew 7:7, an odd choice for a Jewish writer: Ask, and it shall be given you; seek, and ye shall find; knock, and it shall be opened unto you. My own knocking had opened far more to me that I had imagined.

***

Skir grew into his identity as a gay Jewish man in New York of the 1950s and ’60s. While studying at Columbia, Skir spent the summer of 1951 on a kibbutz in Israel but was disappointed to find that his burgeoning sense of his homosexual identity was not welcome in the kibbutz’s heteronormative environment. He wrote in a 1965 reflection: “In those three years [since the hakhshara farm] I had been to Israel, returned. I had grown older, discovered I was a homosexual, decided not to live in the kibbutz, which is a community of married couples. They had socialism, property was shared, but love coveted. I could not bear to be alone in that isolate community. To me the kibbutz had been the reason for going to Israel. So I was no longer a Zionist. Indeed I felt I was nothing.”

Returning to New York, Skir graduated Columbia in 1953 and began writing short stories and essays. He received his M.A. in English from NYU in 1964 and tried unsuccessfully to find a position as a college lecturer. He also became involved in emerging gay and lesbian activist groups, joining the Mattachine Society and participating in the Annual Reminder protests of the East Coast Homophile Organizations in front of Independence Hall in Philadelphia. A photograph from the second annual Reminder Day protest in 1966, now in the Barbara Gittings and Kay Tobin Lahusen Collection at the New York Public Library, shows Skir marching with a sign simply reading, “Equality.” The look on his face is complicated: a mix of determination, resignation, relief, anxiety, and quiet pride.

After the Stonewall Riots of 1969, he was among the group that founded the Gay Activists Alliance along with Arthur Bell, Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, Marty Robinson, and others, and Skir was a proud participant in the first Pride march—the Christopher Street Liberation Day parade, on June 28, 1970. In a report that he published three months later, Skir recalls meeting a friend of his, a former yeshiva student from the Lubavitcher Hasidic community, whom he had persuaded to join them:

Two weeks ago, I had said to him, “You can cure yourself. In a day, a minute, a second, with three words, with six. I’m-not-sick—three words. Three words more: I-love-myself.” And now he’s beside me (magic!) though he told me two weeks ago that he couldn’t, just couldn’t, come out in the open. And now he can and he is SO happy. He’s clutching his book of poems (Anna Akhmatova, translated), marching along. Alone now, but not for long. Now we are together.

Even now, Skir’s prescription still resonates powerfully; in his time, when the idea of a therapeutic or medical “cure” for homosexuality was widely accepted (and attempted on many, including Skir himself, who suffered through hours of therapeutic “analysis” in the 1950s), it was radical.

***

The Leo Skir Papers are being processed in the Tretter Collection archives at the University of Minnesota, where they will be conserved and made accessible to scholars in perpetuity. My preliminary inventory has revealed that the boxes contain all kinds of correspondence, article drafts, unpublished manuscripts, and other ephemera—a treasure trove of primary sources from the experience of a gay American Jewish writer in the middle of the 20th century.

Skir was certainly not the only gay activist who happened to be Jewish, but he was the only one who engaged so explicitly with his Jewishness at a time when these two identities were weaponized against each other (if connected at all). But although he was clearly adamant about his connection to Judaism, he struggled nonetheless. In 1969, he wrote in another essay for The Ladder that once he came out as gay, “I felt quite lost. My Jewish background had prepared me for a different type of exile, a different form of disapproval than that which faced me. Where were my people? Who were my people?”

His papers demonstrate his many attempts to find “his people,” both in the center and on the margins of American Jewish life. He tried out Shlomo Carlebach’s House of Love and Prayer in San Francisco, but found it too “chaste”; he was similarly disappointed with the new countercultural community of Havurat Shalom in Boston, which he satirized as “the House of Discreet Revolutionary Judaism,” writing that “the Havurah is very willing to dump the whole homosexual-Jewish thing in the lap of someone else and somewhere else.” He spent another year in Israel, but apart from a few fleeting sexual encounters, he found no lasting community there. His archive also documents his attempts to work with American Jewish institutions: For example, in 1966, Skir wrote a personal letter to Marion Magid, editor of Commentary magazine, protesting against workplace discrimination against homosexuals and urging her to speak out and make a statement; in another letter to his friend and fellow activist Dick Leitsch, he complains that he received only a lukewarm response. Luckily for us, though, copies of both these letters were preserved in his archives, so that we can trace the different strategies of gay activists in this period.

By the mid-1970s, however, Skir had lost much of his energy for activism; he moved to Minneapolis and eked out a living as a film and theater critic (he was bored by In and Out, disappointed by Rent, and loved The Full Monty). By the time he died in 2014, at the age of 82, the only acknowledgment was the brief death notice in The New York Times: “Skir, Leo. Died on October 9, in Minneapolis, MN. Formerly of New York. Graveside service: Sunday, October 26.”

It would be easy to feel bitter (as Skir himself was) about the opportunities he was denied, and to wistfully imagine what he might have done, had he lived even just a few years longer. But Skir did succeed in publishing a revolutionary, reflective essay titled “To be a Jew and a Homosexual” in 1972 in Sh’ma Journal; this is, to my knowledge, the first personal account of an openly gay Jew to appear in an American Jewish publication. Skir argued that while homosexuality was not incompatible with Jewish values, homophobia certainly was. He concluded by describing the lambda—a symbol of gay and lesbian pride used before the rainbow flag—as a sign “not for sodomy or homosexuality. It is for liberty, for pride, for justice; not for homo-sex, one-sex society, the men-all-together; but for men-and-women-together-equal. And wearing this same sign, though hidden, many Jewish women and men, through our history, lived and died. … I ask for those gays who are Jews a place in the People of Israel.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Noam Sienna is a doctoral candidate in Jewish History at the University of Minnesota; his anthology of LGBTQ Jewish History is slated for publication in 2018.