Grandparents were like mythical beings, like hobbits or unicorns, when I was growing up in Melbourne, Australia.

At my late brother Marvin’s bar mitzvah in 1960, the oldest people present were my parents and their peers: I had one uncle on my mother’s side, and three aunts on my father’s side. (We called all older people—meaning anyone our parents’ age—“Auntie” and “Uncle,” but they weren’t actually blood relatives.) My mother’s parents died young (heart disease, cancer) and I never knew them. My father came from Poland, and everyone in his family, apart from two sisters and one half sister, was murdered by the Nazis.

It wasn’t just that I never had any grandparents. It’s that most people I knew didn’t have any, either. My entire peer group at my small Jewish school were descendants of Holocaust survivors, mostly—unlike me—both parents; Melbourne had the largest population of survivors outside Israel. So most of my friends, like me, did not have grandparents, and while bar mitzvahs were the cause of tremendous celebration—as well as a way to spit on Hitler’s grave—they were often similarly lacking any guests over a certain age.

At the first wedding I went to, when I was 13, the parents of the bride were the oldest people there. I cannot over-emphasize the sense of joy in the air, to be alive, to have survived; every baby born was a victory, vengeance on the Nazi murderers. But alongside the joy there was also the memorializing of the grandparents’ generation that was there only in spirit, not in person.

I remember the first time I met an “old” person: He was, as it happens, the grandfather of my future husband, but I had no way of knowing that at the time. I was about 5, and Reb Zalman, as he was known, had come from Russia via Samarkand and Tashkent and Paris, with his wife and three children (the youngest of whom was destined to become my mother-in-law) as an emissary of the previous Lubavitcher Rebbe, with the mission of establishing Jewish centers of learning in Melbourne. (He talked my dad into sending my brothers and me to the newly established schools, and with me, the religion thing stuck.) Reb Zalman wasn’t even that old at the time, not yet 60, not much older than my father, who was 44 when I was born. But he had a gray beard and twinkling blue eyes and he smiled at me and spoke English and Yiddish (although different from my father’s Poilishe Yiddish) and he gave me a candy. If you could imagine meeting, lehavdil, Santa, or the Tooth Fairy, it couldn’t have made more of an impression.

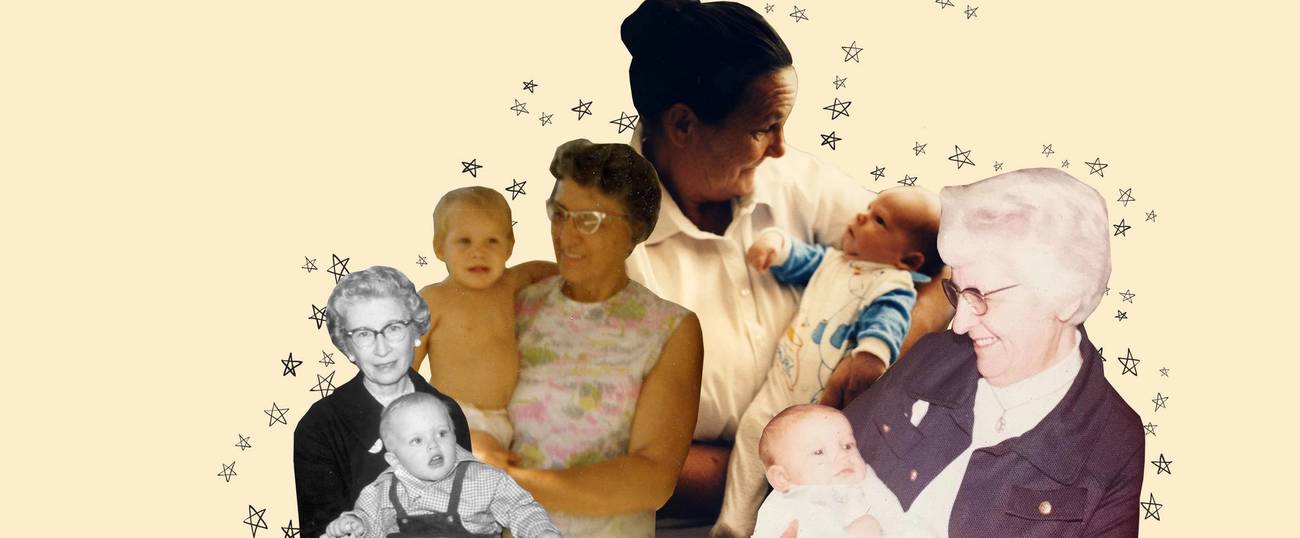

I might have been less impressed if I’d ever had grandparents of my own. But I grew up without the experience of having that older generation in my life. In Jewish Melbourne at the time, this wasn’t unusual. But I never appreciated how that affected me until, decades later, I had grandchildren of my own and had to figure out what being a grandmother meant.

I had seven kids. But my own mother died young, when my eldest, twins, were 4, before she could herself learn to become a grandmother—and be a role model for my later years. And so, it turns out, I never learned how to be a grandmother.

Now I have 17 grandchildren, and I’m still not sure how to be a grandmother. Am I supposed to be there for them all the time, part of the everyday fabric of their lives? Three of my kids, who have seven children between them, live overseas, so clearly I can’t be there all the time. But what of the four who live locally, with 10 children between them? I can’t be there all the time for them, either, babysitting or picking up from school or helping with homework or whatever; if I were constantly available to even just 10 of my grandchildren, I would not have a moment of freedom. I would be swamped.

I’m there for any emergency if I’m in town (because I do travel, largely to visit the overseas kids); I’m always at the end of the phone or the WhatsApp chat whenever there is a medical issue (I’m “Doctor Booba”—the doctor the kids want to come to—but it blurs boundaries and can be confusing for the little ones for me to offer both medical attention and grandmotherly love; pizza one day, an ear and throat exam the next. But I know my limits and I don’t give shots, only stickers and praise.) I have them all over for dinner once a week, and I often do Sunday brunch, apart from Shabbat and festivals. I’ve had grandchildren move in while their parents are visiting with family overseas (all of my kids married Americans, which also means that I am the sole go-to Granny in Melbourne). But as far as a regular spot for babysitting when Mum goes back to work, or scheduled pickups from school? No. I drew the line with that.

My friends—ditto grandparentless—are in similar situations, learning how to be grandparents in real time. I have one friend who looks after a toddler grandchild two full days a week, to enable her daughter to return to paid work. The child is sweet but my friend sometimes feels trapped. I have several friends whose involvement in raising their grandchildren is so extensive that I question the competence of their children, who, as far as I know are compos mentis and not drug addicts or anything. I marvel, but in a rather critical and judgmental way, at this de facto parenting of grandchildren. They seem to enjoy it, so good for them. But: Not for me. Nisht far mir. NFM.

I did the hard yards already in Mummyland, as a largely motherless mother, raising my brood and to tell the truth, by the time I had No. 7, I was already kind of over it all. I can’t go back there.

So what I do now do is what I like to do, and that is feeding them (what happens at Booba’s, stays at Booba’s) reading to them, and taking the older kids to movies and shows. I’m not much for parks and jumping on trampolines and such. I’ll leave that to the Active Grannies. I try not to undermine parents and I insist on “please” and “thank you” and good manners, but I aim to indulge them, while still learning what that actually means.

That’s how I’m doing it; maybe the friends who take over the parenting from their own children have swung too much the other way. Same problem, I guess: no role models.

So now here I am; an un-grandparented and barely mothered grandmother, with a penchant for self-criticism and a strong sense of duty, not to mention capacity for hard work. I try to remember to give the hugs that I rarely got and the praise that I hardly received, and it is still pretty consciously enacted, or reactive rather than proactive. I’m not sure that I can change much more because I’m not getting any younger and my capabilities are not infinite. But I’ll never stop trying. I tried being the floury-aproned granny—Lord knows I’ve got the bosom—but it turns out I can’t stand cooking with little kids. So one fantasy already died. I’ll read with them, and draw and tell jokes and do funny dances, and give gifts, and try not to get too peeved with boisterous and annoying behavior.

This spring, our whole clan—with all seven kids, and all 17 grandchildren—celebrated Passover in Whistler, British Columbia. The logistics of bringing all those people in from around the world were pretty insane; in all, we were 33 people. That’s more people than had been at my brother’s bar mitzvah in 1960. My husband and I—and my mother-in-law—presided like royalty over the magnificent seder table. It was marvelous. “In every generation, they rise against us, to make an end to us,” the haggadah tells us, “but the Holy One, blessed be He, saves us.” And I couldn’t shake the feeling that I remembered from the celebrations of my childhood: Hitler is dead, we’re alive. And if part of being alive is figuring out exactly what it means to be a grandmother, I’ll keep making it up as I go along.

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.