Jewish Marriage 101

‘Kallah’ classes have long taught women the basics of Jewish marital etiquette, from the mikvah to the kitchen to the birds and the bees

Before taking her place as a member of the House of Windsor, Meghan Markle was schooled in the fine points of royal court etiquette. Before taking her place as a married woman of the House of Israel, an observant Jewish bride is schooled in the fine points of traditional Jewish marital etiquette. Known in Hebrew as taharat hamishpocha, or family purity, it entails sexual abstinence as well as a monthly visit to the mikvah, a communally maintained pool of rainwater where ritual immersion takes place.

More discreet of a practice than, say, keeping kosher, it’s not something you can pick up just by hanging around the house. Taharat hamishpocha has to be carefully taught. Enter the bride, or kallah, class. (Opportunities for the groom are also available these days, but they’re far less popular and not nearly as longstanding as their female counterpart.)

Instruction in these intimate matters is conducted one-on-one, between the bride and a female teacher, or within a sisterly group setting. Digital venues such as the Jewish Bride Institute, which makes use of Facebook as well as online instructional videos, are within reach as well. Some kallah classes are taught by the rebbetzin of the community. Others are led by women—let’s call them informal educators – who have dedicated themselves to spreading the word.

Whatever their credentials, they teach their young and often inexperienced charges the ins and outs of sexual congress, what to expect when going to the mikvah, and the intricacies of Jewish law governing marital relations. For good measure, some kallah classes go well beyond the birds and the bees by providing instruction on how to run a kosher household and by offering crash courses in relationship building and financial planning, too.

Most flourish within the orbit of Orthodox Judaism, where observing the laws of family purity and immersion in a mikvah are mandatory rather than volitional activities. Of late, though, pre-nup classes are also finding a home within more liberal circles, where they’re more likely to be called “marriage preparation” and to appeal to the couple, not just to the bride.

In much the same way that the use of the mikvah has become increasingly popular across the board, or, to use the contemporary lingo, more “inclusive,” pre-nuptial classes are springing up here and there. New York’s 92nd Street Y, for instance, offers “After the Huppah: Making Marriage Work,” a 10-session course on intimacy, conflict resolution, and communication skills. Meanwhile, across town, the Marlene Meyerson JCC hosts “Sowing the Seeds of a Healthy Marriage,” where guest experts hold forth on what takes to build a loving and stable Jewish home. At Mayyim Hayyim in Newton, Massachusetts, a community-wide mikvah that seeks to “reclaim and reinvent” the ancient ritual of purification, happy couples can enroll in “Beyond the Huppah,” a five-part series that “provides strategies, insights and tools to help solidify a strong partnership and explore ways of creating a Jewish home.”

Be they Orthodox or post-denominational, latter-day champions of family purity and ritual immersion draw on, and harness, a host of familiar buzzwords to promote the practice. In hushed tones, they speak of tapping into and channeling divine energy, of celebrating femininity, of feeling special—like a princess; of transformation and renewal; of a “spa for the soul.”

Still, outside of Orthodox Jewish circles it’s a tough sell and has been ever since America’s Jews embraced modernity with relish and gusto. Little about taharat hamishpocha appealed to the aspiring, middle-class Jews of the interwar years. They found it increasingly difficult to reconcile their rising standards of personal hygiene and emotional intimacy with the mikvah whose fidelity to cleanliness and all too public nature left a lot to be desired.

The ritual’s accompanying rhetoric of “pure and impure” didn’t sit well with them either, challenging their sense of themselves as modern, sophisticated beings. By the 1920s, the mikvah appeared to be on its last legs and family purity honored more and more in the breach. Surely it’s not for nothing that its beleaguered proponents took to describing the ancient Jewish rite as the “Cinderella of Jewish rituals.”

Lest the mikvah end up the stuff of a fairy tale, a number of peppy prescriptive texts appeared in English during the interwar years to promote—and safeguard—its virtues. Sounding more like Good Housekeeping and other popular women’s magazines of the day than sober religious compendia, publications such as The Three Pillars and The Duty of the Jewish Woman called on modern American-Jewish women to retain the practice, not cast it out from their daily lives. Contemporary notions of well-being and happiness lay at the heart of their entreaties. The observance of family purity “provides a sense of renewal and fulfillment,” they wrote. It “prolongs [a woman’s] youth, beauty and attractiveness.”

And it benefited Jewish men, too. As Hillel Kauvar, a Denver rabbi and professor of rabbinic literature at the University of Denver, would have it, taharat hamishpocha was a form of “Jewish gymnastics,” a “training school in self-control.”

By far the most consistently deployed and presumably the most resonant claim on behalf of taharat hamishpocha had to do with its putative health-giving properties. Among the five reasons the Orthodox Union put forth for its retention was that “medical opinion supports it and science has proved it.” (The first reason: God had commanded it.) According to a number of widely cited scientific studies of the time, among them Hiram N. Vineberg’s “The Relative Infrequency of Cancer of the Uterus in Women of the Hebrew Race,” which appeared in the 1919 issue of Mount Sinai Hospital: Miscellaneous Writings by the Attending Staff, Jewish women who practiced sexual abstinence and ritual immersion had a much lower incidence of cervical and uterine cancers than those who did not.

Fair enough. But what if an observant Jewish woman preferred to immerse herself in a bathtub rather than the mikvah? “No, a thousand times, no,” emphatically responded Jacob Smithline, a Brooklyn physician and the author of a study titled “Scientific Aspects of Sexual Hygiene.” By his lights (and in this he was not alone), there was something in the “living waters” of the mikvah—its mineral properties, perhaps—that fully irrigated a woman’s private parts, rendering her clean, inside and out. A bath or a shower simply would not do.

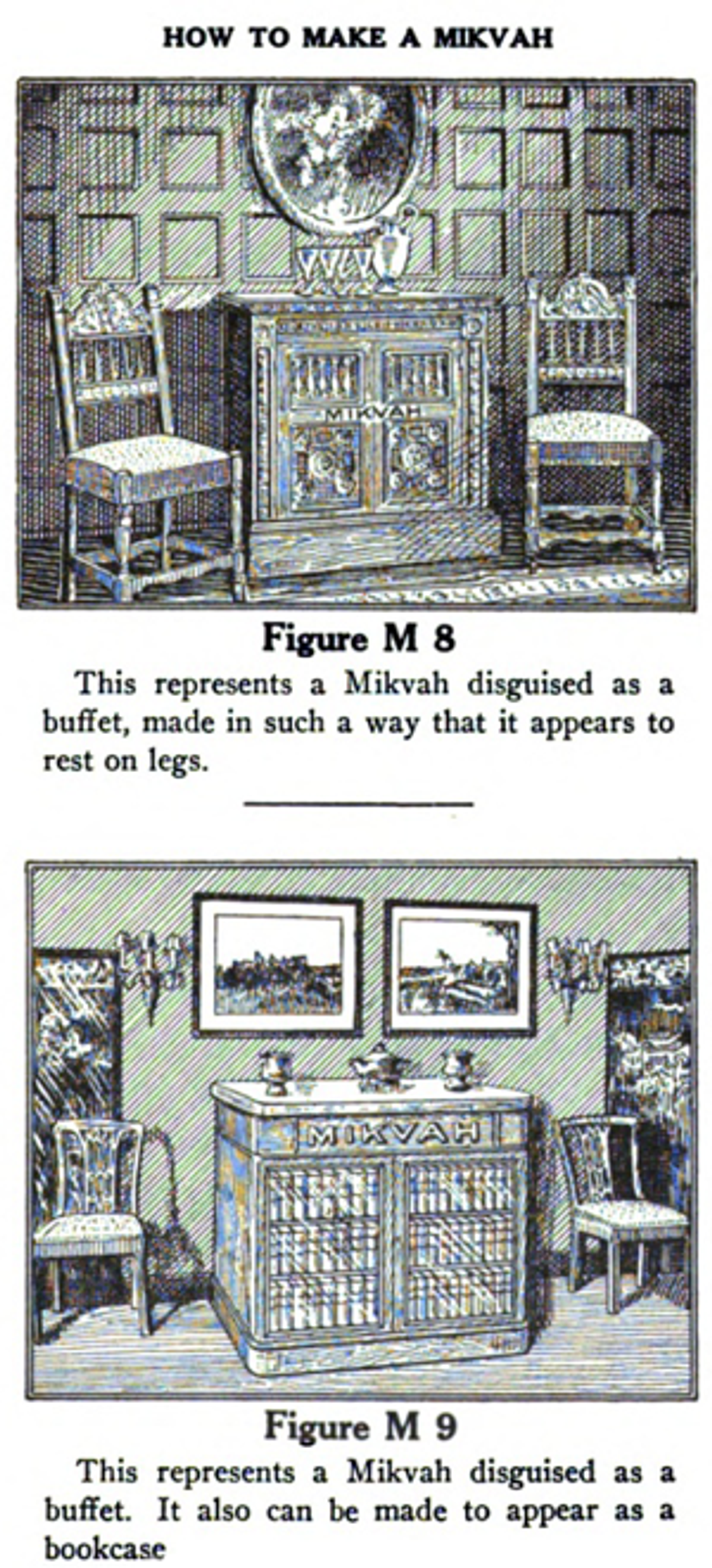

In an imaginative attempt to overcome that hurdle, a California rabbi by the name of David Miller, the author of a privately published, 500-page text from 1930 with an equally lengthy title, The Secret of the Jew, His Life, His Family: A Marriage Guide—How to Stay Married; What a Married Daughter of Israel Must Know, proposed to privatize the mikvah. If he had his druthers, every American Jewish household would have a ritual pool all its very own—and not any old ritual pool, but one that was “deluxe.”

A spacious, well-appointed bathroom where the mikvah was integrated into the design of a shower stall was one sensible setting Miller proposed. A modern living room, where the doors to a handsome wooden cabinet would open—abracadabra! —to reveal a ritual pool, was another, far less practical proposition. (Wouldn’t water drip on and ruin the rug?) Detailed architectural plans as well as drawings for those who might have trouble conjuring up the kinds of fanciful facilities the rabbi had in mind accompanied the text.

In seeking to accommodate his middle-class readers, Miller gets points for trying. But he missed the boat. The notion of a private mikvah did not take hold, a failure that had little to do with finances or with some of his arguably daffy ideas and everything to do with the larger matrix in which taharat hamishpocha was embedded: the communal nature of married life. Kallah classes might speak of “Judaism’s refreshing view on womanhood” and salutes to the mikvah might extol its benefits, but in the end what was, and continues to be, at stake is the union between the individual and the collective. Maintaining the family purity laws is Judaism’s way of keeping the Jewish people afloat, one couple at a time.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Jenna Weissman Joselit, the Charles E. Smith Professor of Judaic Studies & Professor of History at the George Washington University, is currently at work on a biography of Mordecai M. Kaplan.