Responsive Reading

Two gay congregations publish non-traditional prayer books

For Gay Pride Shabbat, which begins this evening at sundown, two of the most influential gay synagogues in the country will be using new prayer books, or siddurim, each of which, the congregations’ rabbis believe, will revolutionize the liturgical landscape.

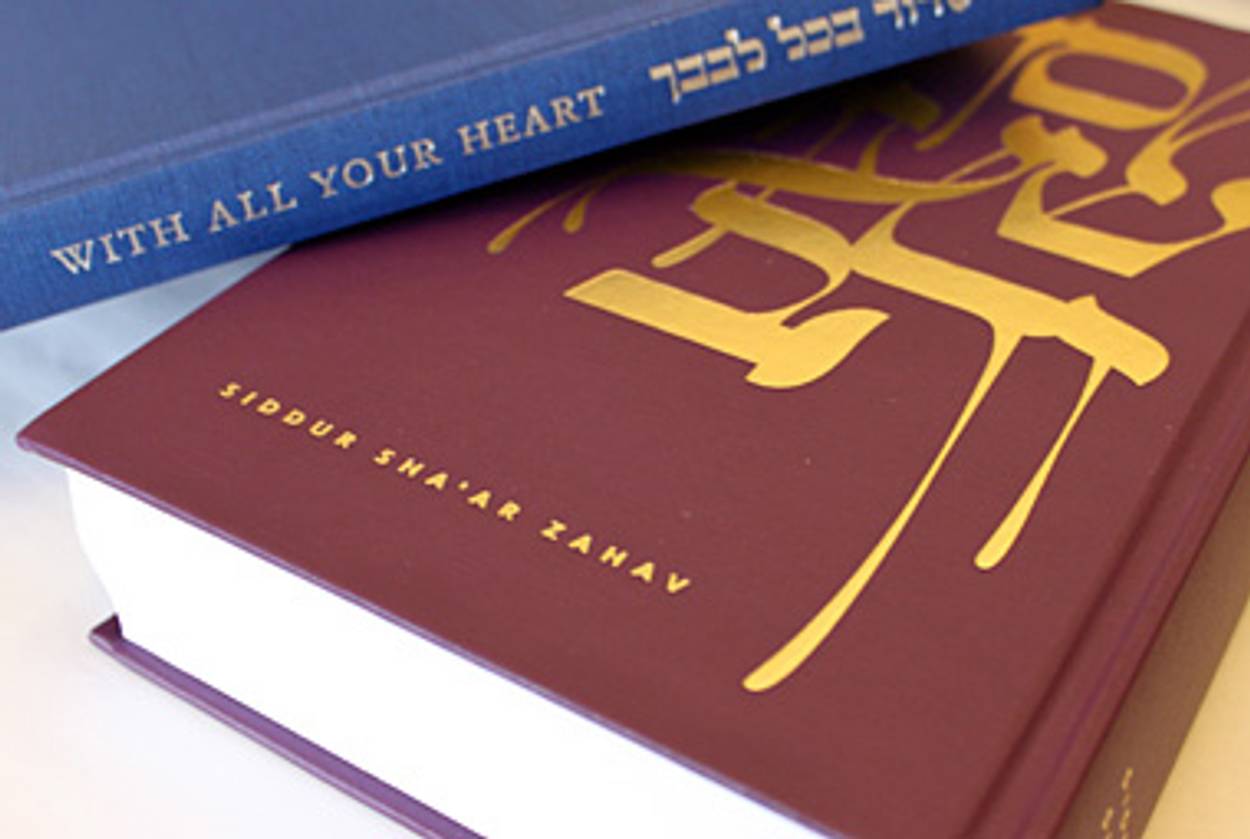

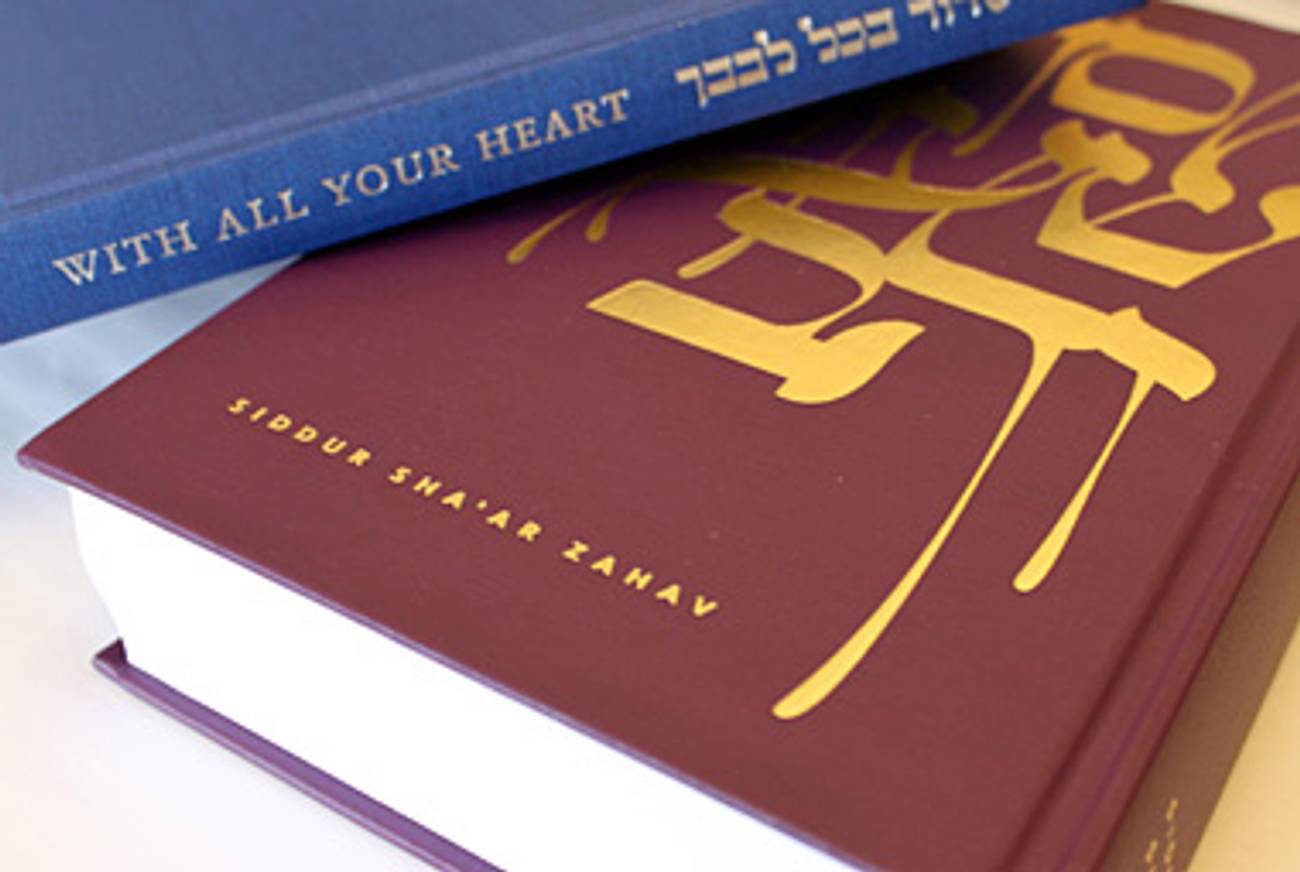

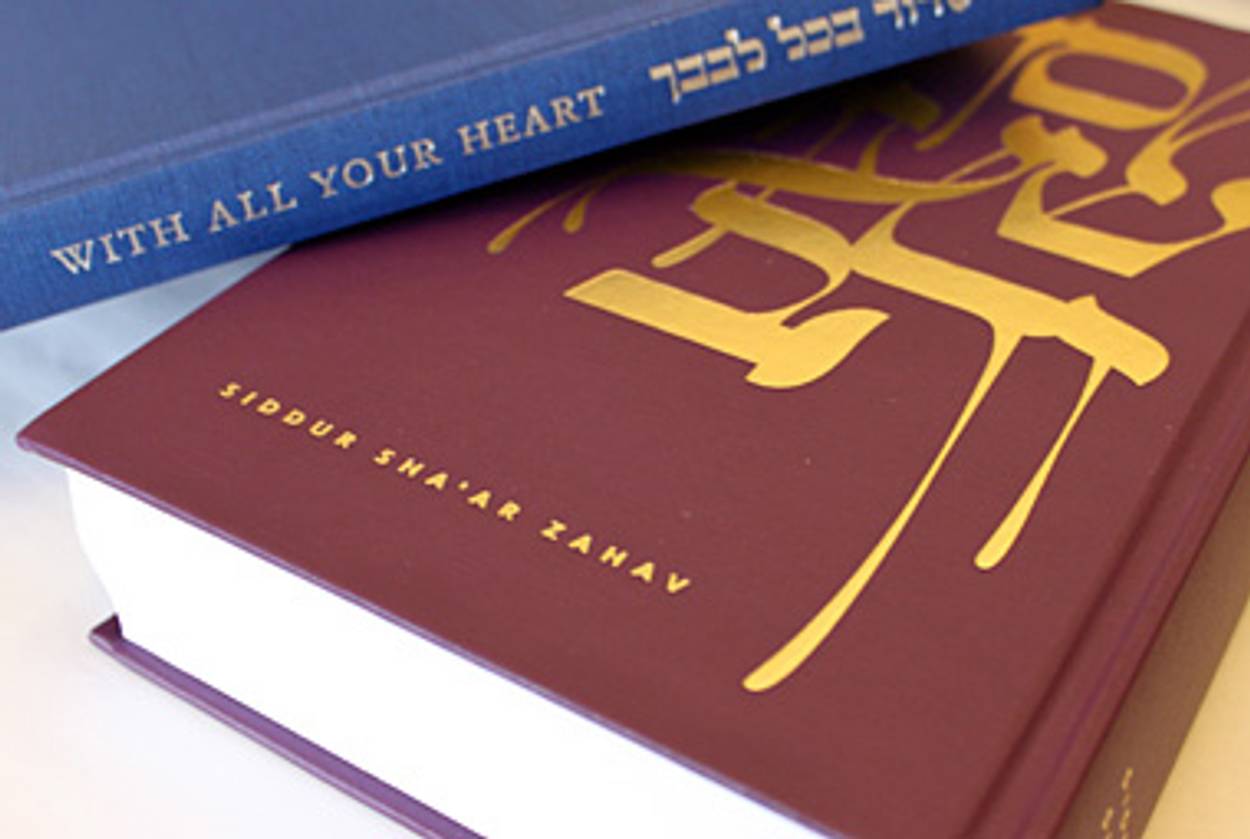

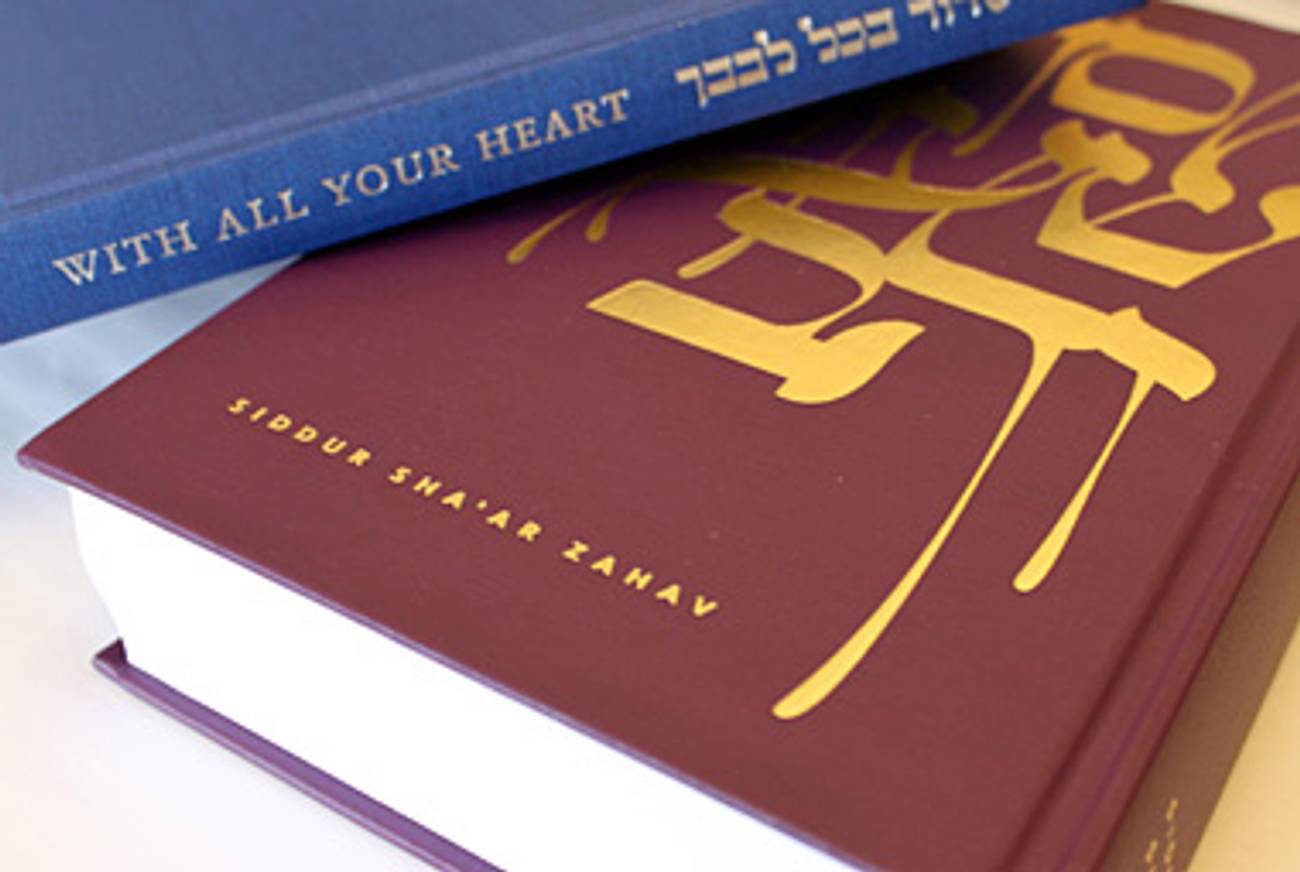

Sha’ar Zahav, the siddur named for the San Francisco congregation that published it, and Siddur B’chol L’vavcha (“With All Your Heart”) from New York City’s Congregation Beth Simchat Torah were released this month, after 10 years of work on each, and are intended for Jews from all denominational backgrounds. What sets the two apart from each other can crudely be signified by their coastal affiliations; Sha’ar Zahav, hailing from California, has a more all-embracing hippie philosophy, while the CBST siddur is more efficient and academic in approach.

Siddur Sha’ar Zahav begins with new prayers, written by Rabbi Camille Shira Angel and her congregants, marking milestones absent from traditional prayer books. There are meditations “For the Partner of Someone in Gender Transition,” “For Letting Go of Having a Biological Child,” “For Taking an HIV Test,” and “For Questioning Sexuality.” Traditional prayers are edited to include both “masculine” and “feminine” language, and a few offer “feminist” language (referring to God as the “Well of life,” rather than “Ruler of the Universe,” which some see as patriarchal). It provides refreshingly metaphorical interpretations of prayers with controversial literal meanings, such as the Shema, which, the siddur notes, “articulates a theology of divine reward and punishment that many Jews do not accept,” and which the siddur suggests might be an ecological warning.

Sha’ar Zahav’s prayer for those who don’t believe in a traditional idea of God declares, “I invent my own religion”—a religion that honors “bones of calcium phosphate,” Albert Einstein, and composting. “I’m a believer, but the ‘Contemplation for the Nonbeliever’ is gorgeous,” Rabbi Angel said in an interview. “If someone can access these words because it says ‘this is for you,’ it doesn’t profane the religion as we’ve inherited it.” The siddur’s “Queer Amidah,” which remarks to God, “How queer of You to have created anything at all,” is intended more as a preparatory group reading, rather than a replacement for the traditional silent meditation, Angel said.

For the blessing recited before aliyot (when individuals are called up to sanctify the chanting of a portion of the Torah reading) , Sha’ar Zahav offers both masculine, plural, and non-gendered language for the honorees. (Because the CBST siddur offers only a Friday night service, it does not include any of the prayers surrounding the Torah reading, which takes place on Saturday mornings.)

Sha’ar also focuses on sexuality in its prayers, a result, Rabbi Angel said, of feminism’s embrace of the physical. “Whoever was the original male editorial board missed the opportunity to lift up bodies and different shapes and different abilities,” she said. “To only refer to the body [in ways like] ‘the blind shall not stumble,’ it’s like, lets honor the ripening of our bodies,” she says, referring to a prayer for the onset of puberty in Sha’ar Zahav. Angel sees the creation of the siddur in terms of childbirth. “Whatever the struggles were during pregnancy and delivery,” she says, “I’m like, lets start working on a machzor [high holiday prayer book].”

CBST’s B’chol L’vavcha, on the other hand is peppered with poems by Tony Kushner, Muriel Rukeyser, and Adrienne Rich, few of which directly address gay issues. The prayers switch between masculine and feminine language for God, aiming for balance. Its margins offer interesting factoids and notes—the KKK forbade members from singing “God Bless America” because it was written by the Jewish Irving Berlin and there’s a connection between the gay-pride flag, the Stonewall Riots, and the story of Noah, for whom God created a rainbow as a way to say “I will never destroy you again, and it’s now up to you to create a universe you can be proud of,” according to the siddur.

Where Sha’ar Zahav offers a separate women’s Amidah, CBST has made a subtler change, adding to the list of matriarchs the names of Bilhah and Zilpah, concubines of Jacob who gave birth to several of the men that would go on to form the tribes of Israel. “In our community there are so many parents who don’t have legal protections, but are loving parents of children,” explained Ayelet Cohen, the congregation’s associate rabbi.

CBST has modified “Lecha Dodi,” a traditional song comparing God’s love to the love of a groom for his bride, to say instead “as a heart rejoices in love.” “It was very important to us that it fits the music,” said Cohen. Their siddur also modifies the prayer “Ma Tovu,” which celebrates the coming together of a community and traditionally only mentions brothers. “We already see versions that include women, but even that assumes a binary concept of gender,” Cohen said. “So we include a third line, that we are all gathered together.”

In addition to the Friday night service, B’chol L’vavcha also includes liturgy for the holiday cycle. There are also prayers for events like comings out, baby namings, and the formation of committed relationships. But the siddur is “conscious not to suggest a particular order that these things should happen in life,” Cohen said.

While both siddurim focus on inclusiveness, Sha’ar Zahav does so by including prayers to suit every variety of gender identity and every aspect of the gay experience. By contrast, B’chol L’vavcha by and large contains one version of each prayer, designed to suit as many people as possible. They both include sections honoring World AIDS Day and the Transgender Day of Remembrance, but while CBST marks these days with poems and readings by celebrated authors, Sha’ar Zahav creates traditionally formatted liturgy for the occasions.

Rabbis from both congregations reject the idea that there is anything divisive about having more than one gay-friendly siddur. “I don’t think that reflects anything new,” said Sharon Kleinbaum, the senior rabbi at CBST. “Synagogues throughout Jewish history have created siddurim that reflect their communities.”

Hadara Graubart was formerly a writer and editor for Tablet Magazine.

Hadara Graubart was formerly a writer and editor for Tablet Magazine.