School Ties

Ivy League style, the quintessentially WASPy American look defined by Jewish designers a century ago, returns to the runways for Fashion Week

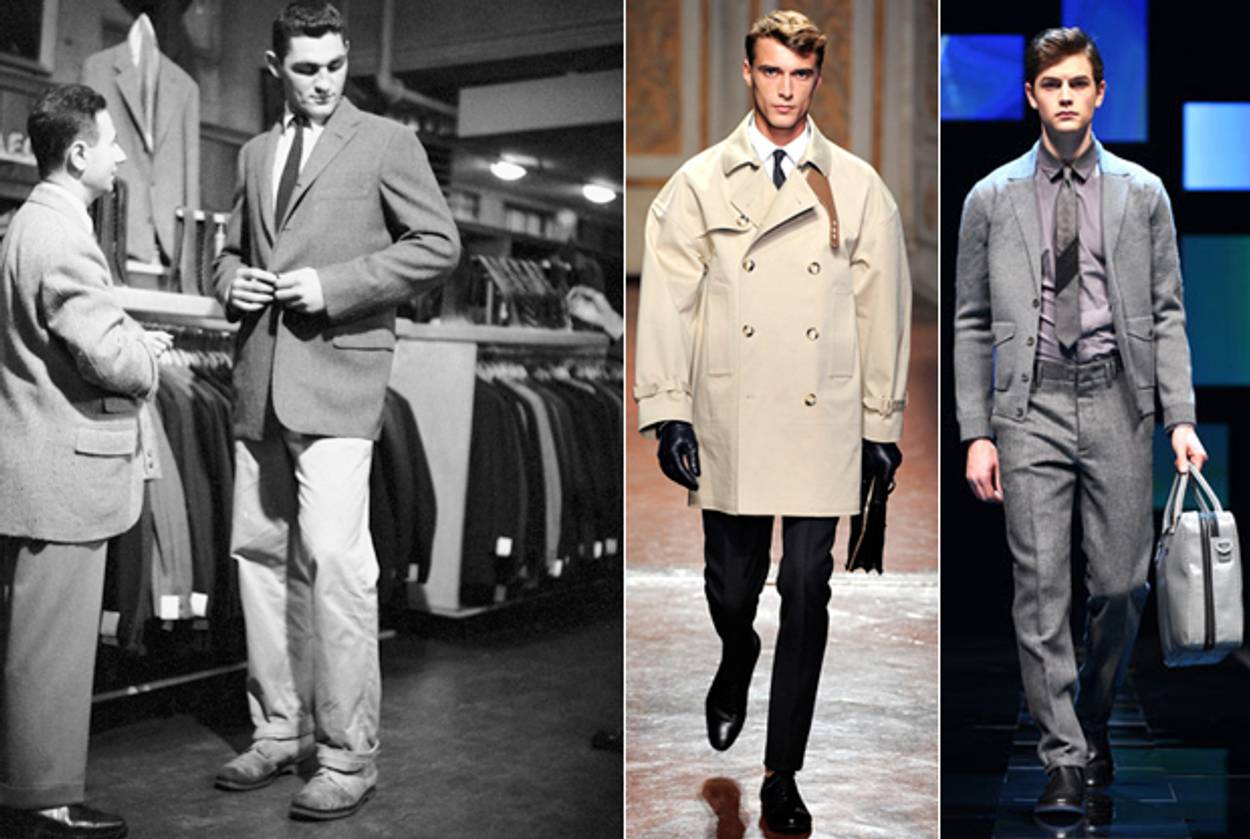

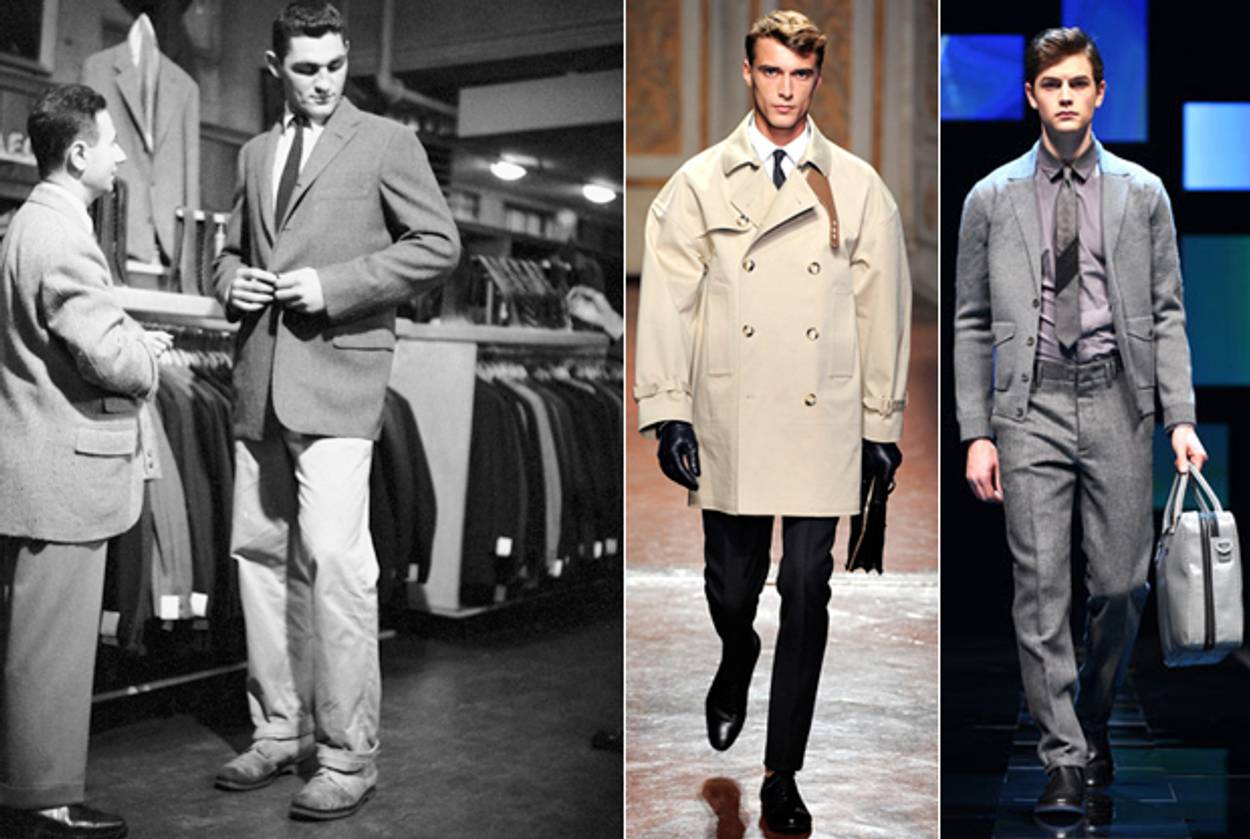

When Valentino sent models down Milan runways last month to show off the new fall collection for men, the clothes were informed not by Lisbeth Salander’s trendy gothic grunge, but by classic Ivy League aesthetics, from oversized lettermen jackets to classic trenchcoats in shiny leather. Fendi recalled similar themes in its show, finishing jackets with details pulled from cardigans and schoolboy blazers. If Milan was any indication, New York Fashion Week—starting Feb. 9—will also feature echoes of the Ivy League style made famous on the campuses of Princeton, Dartmouth, Harvard, and especially Yale, many decades ago.

Whether worn by a model or an industry insider or a chic spectator watching the fall collections come down the runway, Ivy League—also known as “trad,” a precursor to preppy style—is definitely back in vogue. Just look at the lettermen jackets going for a thousand dollars in vintage stores, or the models in J. Crew ads sporting penny loafers without socks. The only thing hidden in this resurgence of a quintessentially American style is a sense of its Jewish roots.

The Jewish influence on menswear in general is well-known, from wholesalers peddling the fabrics that make ties, shirts, and slacks, to the tailors and the retailers and the designers themselves—Marc Jacobs, Isaac Mizrahi, and of course, Ralph Lauren (né Lifshitz) continue to define modern fashion. But Jewish designers’ role in creating the Ivy League look has a distinct context, because these designers created the signature style for a world that wouldn’t admit them.

David Weinreich started the tradition in 1896 by opening Weinreich’s, a shop in New Haven, Ct., that sold custom suits. Two years later, Arthur M. Rosenberg opened Rosenberg’s, where “Rosie” would reign as the original Jewish King of the Custom Made Suits in New Haven well into the Roaring Twenties. In 1902, Jacobi Press opened his own store on Yale University’s campus, where he perfected his three-button sack suit jacket and inspired a dozen imitators that catered to the Ivy League’s finest.

Jacobi Press had emigrated from Latvia in 1896 with every intention of continuing his rabbinical studies, but, like many Jews to arrive in America at the time, he put his religious training aside, to work for his uncle’s custom tailoring business in Middletown, Ct. Press’ grandson, Richard Press, carries on his grandfather’s legacy as the preeminent historian of the classic look: He is a contributor at the blog Ivy Style, where he dishes the old gossip and tidbits that would have been otherwise lost to history. Press—who flew the coop for Dartmouth, only to return to New Haven to work for the family company from 1959 to 1991—says his grandfather never forgot his Jewish roots, becoming the first Russian Jew to become a member of the local German Reform temple in 1902, and keeping a collection of Judaica and Talmudic studies in his personal library.

By the 1920s, J. Press had become the choice tailor for everyone from Duke Ellington to Cary Grant. Even though F. Scott Fitzgerald is said to have shown up to military training wearing a Brooks Brothers suit, Press says the man responsible for one of America’s greatest novels was, in fact, a customer of his grandfather in the 1920s, and in a 1936 letter to his then-15-year-old daughter, Scotty, Fitzgerald cautioned the teenager to “beware of the wolves in their J. Pressed tweed.”

By the 1950s, the look was inescapable. After Rosenberg retired, two former J. Press employees, Sam Kroop and Mack Dermer, acquired his brand in 1958, shortly after “The Ivy Look” began landing full-page spreads in major magazines, starting with Life magazine’s “The Ivy League Heads Across The U.S.” in 1954.

The Jewish pedigree of this quintessentially American style is undeniable. If you surveyed the Princeton campus on a spring day in 1962 and saw a student from a well-to-do Southern family strolling in a pair of madras shorts with a blue oxford shirt, there was a good chance that shirt was the product of Marty and Elliot Gant: former J. Press stock boys, and the sons of a Ukrainian-Jewish immigrant. The real Ivy League alumni Mad Men who ran the advertising world of New York City wore suits with the Chipp logo from Sidney Winston (another former J. Press employee) on the inside of the jacket. President Kennedy supposedly made the switch to exclusively wearing suits made by New Haven custom tailor Fenn-Feinstein because he admired the ones worn by then Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare Abraham Ribicoff, who would become Connecticut’s first and only Jewish governor.

Yet while Rosenberg, Press, and their ilk were free to measure out fabric, sew together, and create the suits for America’s movers and shakers, Jews were routinely denied admission to the Ivy League schools (especially Yale, the epicenter of the Ivy look) and country clubs frequented by their customers. Schools imposed quotas and restrictions to keep Jewish enrollment low. Richard Press recalls stories about Vic Frank, a Jewish football player in the late 1940s for Yale whom the athletic director tried to kick off the team, and another about a “society fellow” choosing to live in a hotel rather than share his dorm room with a Jewish student.

The quotas are gone, but the influence of those Jewish ateliers still endures today, thanks to modern designers who have once again turned the Ivy League look into a billion-dollar idea.

Ralph Lifshitz, a boy from the Bronx, started out as a salesman for Brooks Brothers (the one brand commonly associated with the Ivy look not founded or owned by Jews) and ended up climbing to the top of the fashion world with Polo Ralph Lauren by perfecting the ultimate symbol of modern trad style: his iconic polo shirt. If you walk into a J. Press store today, you will see that not much has changed since the brand’s inception; there are Yale pennants, pictures of bulldogs (Yale’s mascot), leather couches, and of course, suits. Gant has teamed up with popular young designer Michael Bastain, boosting its brand credibility with the young and chic.

But the influence that those Jewish-owned and -operated companies have is most evident when you look at a generation of Jewish undergraduates decked out in wares by Ivy imitators Steven Alan and Band of Outsiders. They don’t worry about being part of a Jewish quota, or whether or not their roommates will vacate because of their heritage; their biggest worry now is whether or not they’ll ever get back that blazer they lent out to a fraternity brother and if he’d even bother to dry clean it first.

Jason Diamond is the literary editor of Flavorwire and founder of Vol. 1 Brooklyn. His Twitter feed is @imjasondiamond.

Jason Diamond is the literary editor of Flavorwire and founder of Vol. 1 Brooklyn. His Twitter feed is @imjasondiamond.