The Enemies of Our Enemies

The Salafis, Sunni Islamic extremists, are at least opposed to the most dangerous U.S. adversaries, the Shiites

The upheavals of the Arab Spring have given rise to more Sunni extremists than Osama Bin Laden could have hoped for: The Muslim Brotherhood has enjoyed electoral victories in Egypt and Tunisia, and the black flag of al-Qaida flies over parts of Libya. Throughout the Middle East, the Salafis—a Saudi-funded extremist strain of Sunni Islam—are one of the region’s fastest growing movements.

How did we get here? After all, the U.S. war against Saddam Hussein was supposed to jolt Sunni triumphalists—from Saddam’s Baath party to Bin Laden’s jihadis—and the freedom agenda was meant to make moderates out of extremists. But almost 10 years on, Arab democracy has largely empowered those very men in Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, and perhaps eventually Syria, who want to see the world return to 7th-century Arabian society.

Sunni extremists are truly backwards. On the question of basic human values (women’s rights, freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and so on) they could not be more opposed to our worldview. But given the strategic circumstances the United States currently faces, there’s no question they’re less of a threat than Iran and its allies operating under the protection of a nuclear weapons program.

As President Obama demonstrated with his June 2009 Cairo speech, he hoped to have one policy—from his perspective, to put America back on track with Islam—for the entire Muslim world. But that’s not how the Middle East works. It’s a region naturally divided against itself (between Sunni and Shiite, Arab and Kurd, Christian and Muslim) and most dangerous when some demagogue (from Gamal abdel Nasser to Hassan Nasrallah) tries to unify it, since that usually comes at the expense of the United States and its allies—whether that’s Israel or states like Saudi Arabia and Jordan.

We actually need two policies for the Muslim world, one for the Sunnis and one for the Shiites. In other words, we need to distinguish between the various dangers the region presents and choose the lesser of two evils. Right now, that means siding with the Sunnis—even those of the extremist variety.

***

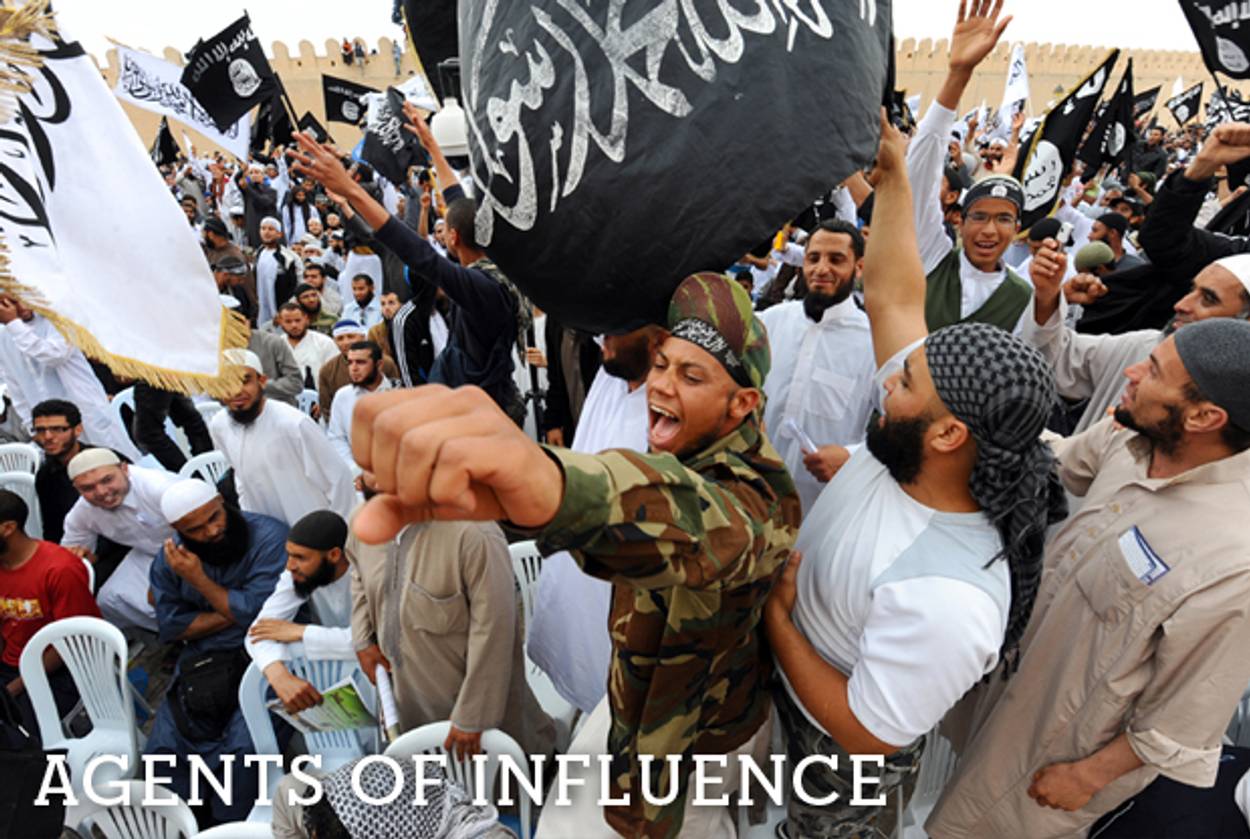

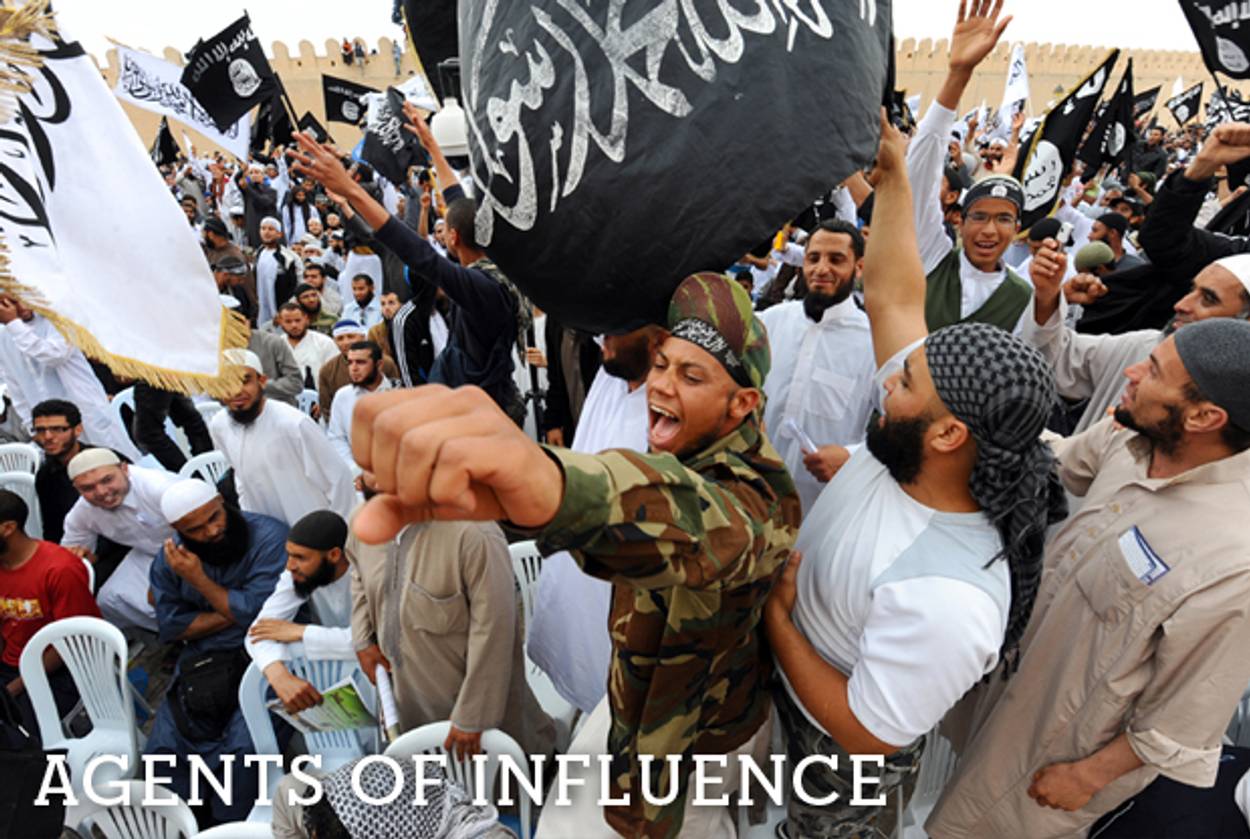

It’s hard to think of a less appealing ally than the Salafis. If there was ever a group that identified themselves as ready to be called to their heavenly reward, it’s this gang of bearded medieval misfits. Recently, thousands of them gathered in the middle of the Tunisian capital to wave black al-Qaida flags and solicit the attention of the president of the United States with the chant, “Obama, Obama, we are all Osama.” It’s no wonder Obama has proudly advertised the crowning achievement of his foreign policy as killing Sunni extremists—including the former emir of al-Qaida, Osama Bin Laden, as well as a host of his subordinates.

Indeed, in the immediate aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks it was difficult not to conclude that Sunni extremists represented the most serious threat to vital American interests, from the security of U.S. citizens to the free flow of Persian Gulf oil. The Bush Administration invaded Iraq to bring down a Sunni regime and thereby send a message that would reverberate throughout the region: The Sunnis, including allied regimes like Saudi Arabia, were on notice.

But a funny thing happened during the course of the Iraq War. It wasn’t just that Washington learned it couldn’t do without the Saudis and their oil. Bush Administration officials also learned that the Sunnis were, compared to the Iranians, the lesser of two evils. U.S. military and civilian officials knew it was the Iranians who were responsible for the preponderance of violence against Americans in Iraq. The Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps had camps on the other side of the border where they instructed their Iraqi assets how to manufacture and use the improvised explosive devices that caused so many American deaths and injuries.

To implement the surge in 2007, the United States managed to turn around plenty of Iraqi Sunnis with cash payments and arms. Not all of those Sunnis were simply from the much-vaunted nationalist cadre called the Sons of Iraq, nobly defending their homeland. Some of those Iraqi Sunnis were full-on Islamists, and yet the United States found a way to work with them. So, why not now, say, in Syria?

The administration contends that al-Qaida may have infiltrated the Syrian opposition, though the evidence it has presented is pretty thin. Moreover, the White House seems willing to ignore that it was the Assad regime that cultivated relations with Sunni extremists to begin with. But for the sake of argument let’s say that al-Qaida is the driving part of the opposition to the Assad regime. So what? The United States cannot afford to play the role of disinterested observer. As odd as it may sound to some, it is better for U.S. interests for a gang of Sunni fanatics to defeat the ostensibly secular Assad regime than it is for a government allied with Iran to continue to wield power.

One fundamental tenet of political strategy is to sequence threats, or to decide who presents the most proximate danger to your interests. The Israelis have no problem with this concept. They recognize that Iran represents threat No. 1, even as the Israelis also see that the Salafis are looming in the near distance and promise to become a serious problem soon.

Apparently this wisdom, or the ability to distinguish between threats, is lost on the current generation of U.S. policymakers. The Obama Administration has let on through press surrogates that it believes it is capable of containing and deterring Iran, just as Washington pushed back against Moscow. However, the successful execution of this policy requires not only the credible threat of military action but the use of proxy forces. That’s why we backed, among many other proxies over the course of the Cold War, the Afghani mujahideen against the Soviets.

But it is precisely the precedent of the Cold War that unnerves many American policymakers: Supporting the mujahideen and the Afghani Arabs set the groundwork for what many call the blowback that led to 9/11. We certainly don’t want to risk anything like that again, they argue.

It’s a fair case, but when looking at the bigger picture, does anyone doubt that it was worth backing the mujahideen to help bring down the Soviet Union, or siding with Stalin to defeat the Nazis? There’s no way to predict what will happen in the future. All you can do is choose allies as situations present themselves.

The question for the Obama Administration is: Who does it want to win this round? Or, what fight can it afford to put off until another day? There is no time to spare with Iran. The day will come for the bearded men waving black flags in a Tunisian square.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Lee Smith is the author of The Consequences of Syria.

Lee Smith is the author of The Permanent Coup: How Enemies Foreign and Domestic Targeted the American President (2020).