Still Terrible

Why the Germans are right to prosecute 89-year-old John Demjanjuk

This May, American immigration agents arrived at the suburban Cleveland home of Ivan “John” Demjanjuk to deliver him to a jail cell in Bavaria. A widely published Associated Press photo caught the 89-year-old Demjanjuk being lifted into an Immigration Services van, eyes closed and mouth agape—an expression of either affected bewilderment or honest despondency. His son protested to assembled journalists that the proceedings were “inhuman.”

Pangs of sympathy for an enfeebled octogenarian, wheelchair-bound and encircled by weeping family members, are understandable. But for those familiar with the story of Demjanjuk, it should be a fleeting emotion. Born in the Ukraine and a former member of the Trawniki SS, Demjanjuk stands accused of complicity in the murder of 29,000 Jews at the Nazi death camp in Sobibor, Poland. Last week, a team of German doctors determined that, despite his advanced age, Demjanjuk was fit to stand trial for war crimes, and yesterday he was formally charged.

Demjanjuk, convicted in an Israeli court of being the notoriously sadistic Treblinka guard “Ivan the Terrible,” saw that conviction overturned by the Israeli Supreme Court in 1993. So why try him again, in a different country? The evidence collected two decades ago strongly suggests that prosecutors in that case had a Nazi guard, just not the one they thought they did.

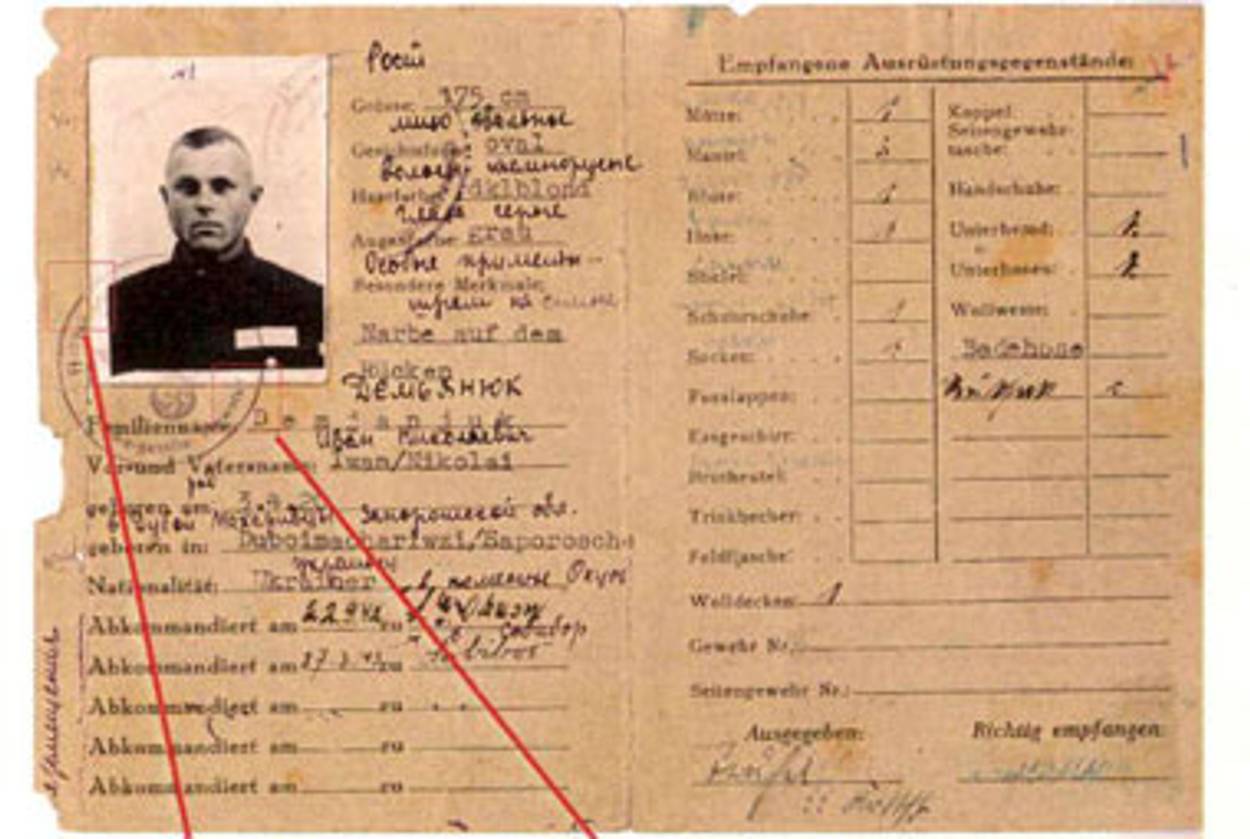

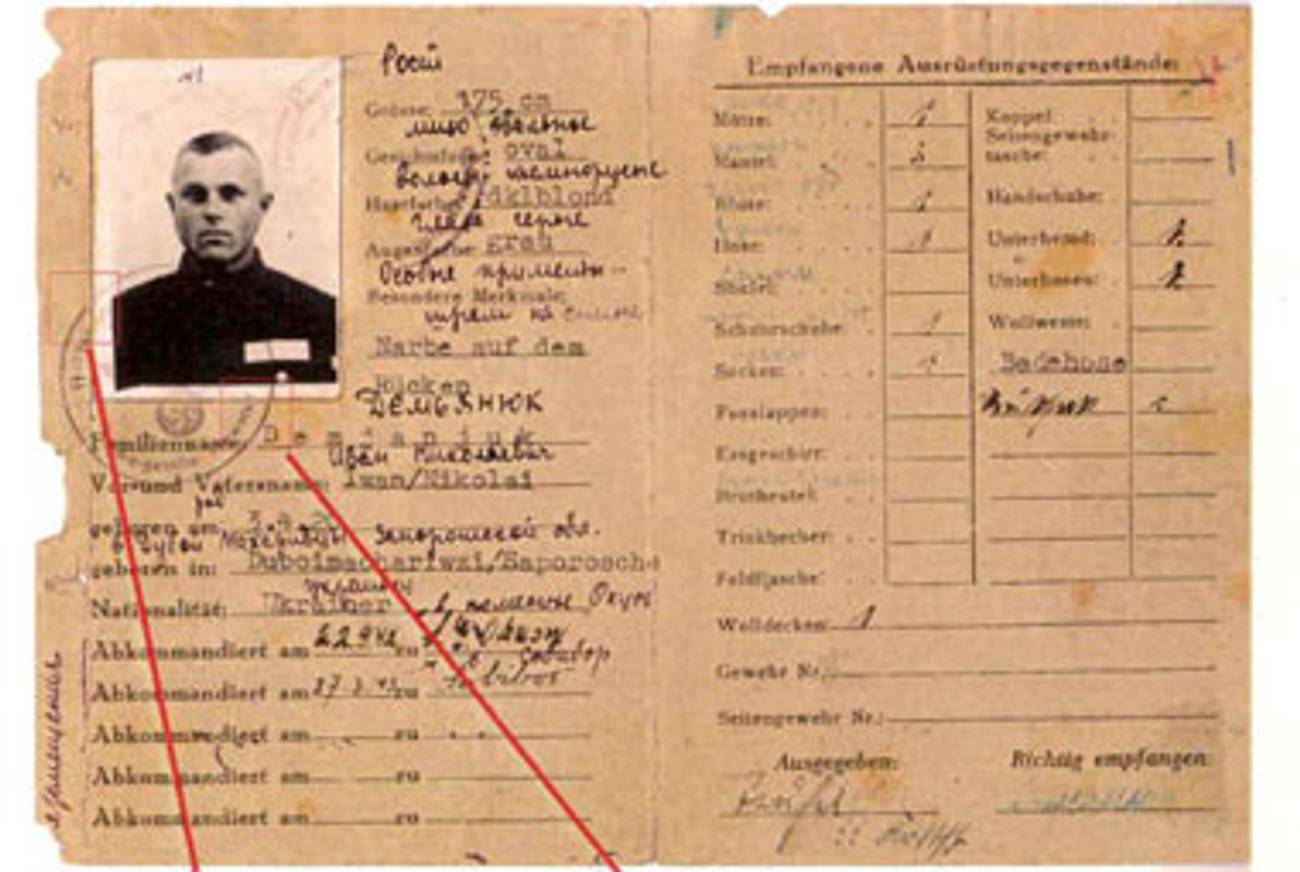

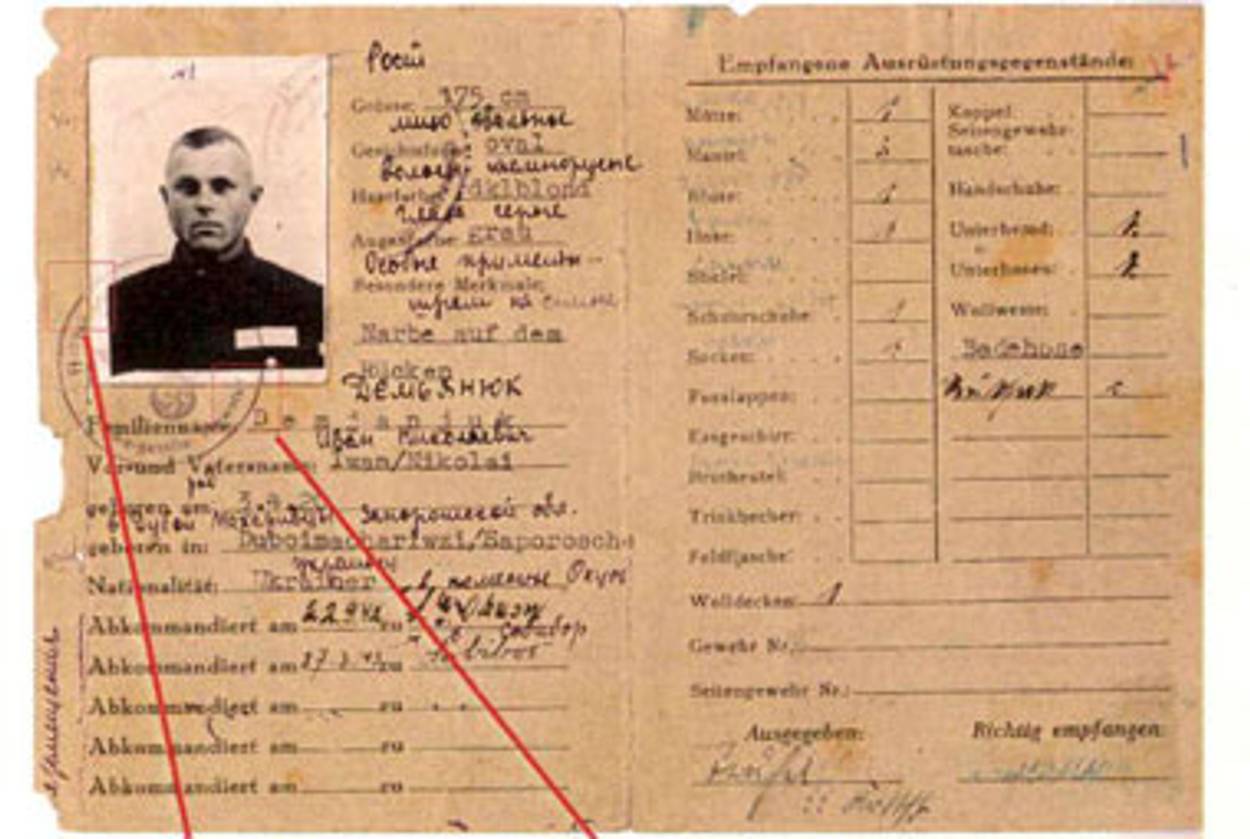

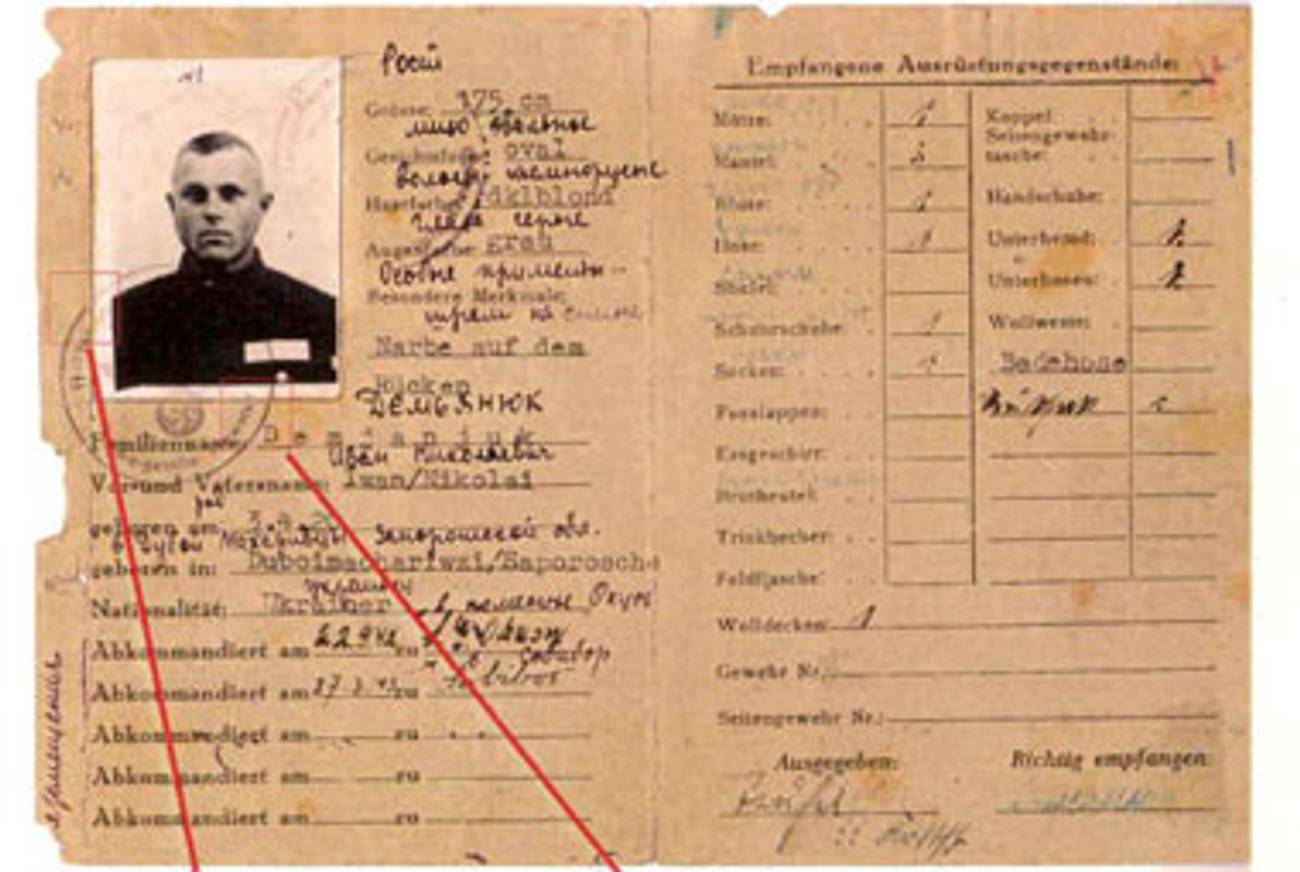

During investigations leading up to his first trial, American investigators obtained—and withheld—an identity card placing Demjanjuk at an SS training facility in Trawniki, Poland, at the death camp at Sobibor, where approximately 250,000 Jews were killed, and at a concentration camp in Flossenburg, Germany. His defenders have long claimed that the document, delivered to prosecutors by the Soviet Union, was a KGB forgery. But that argument has become impossible to sustain: prosecutors later uncovered corroborating documents in the German Federal Archives in Koblenz confirming both Demjanjuk’s military ID number and the timeline of his service in occupied Poland.

When entering the United States in 1952, Demjanjuk listed Sobibor as his primary residence between the years of 1937 to 1943. When questioned on this, Demjanjuk, who admitted that his timeline was a fabrication, claimed to have spotted the name on a nearby map when filling in immigration paperwork, though he later changed his testimony, claiming that a fellow refugee provided him with the town name. But as historian Gitta Sereny notes in her book The German Trauma, Sobibor was “little more than a railway halt in the forest [that] hardly appeared on pre-war Polish maps.” So, asked investigators, if Sobibor was nothing more than a unknown railroad junction—a fact the defense never convincingly challenged—how did Demjanjuk come to choose it as his alleged pre-war home?

To those investigating the “Ivan the Terrible” charges, these contradictions and shifting histories suggested that Demjanjuk was likely hiding a more sinister history. Indeed, an American judge called his oscillating alibis “so incredible as to legitimately raise the suspicions of his prosecutors that he lied about everything.”

While receiving significant coverage in the German media, Demjanjuk’s recent deportation hasn’t been widely debated in this country. But when the news reached conservative columnist Pat Buchanan, he compared Demjanjuk, who admitted having had an SS tattoo under his arm removed after the war, to both Alfred Dreyfus and Jesus Christ. Buchanan deploys an argument—and Google reveals its popularity elsewhere—that is at once reductionist and compelling: what good comes from prosecuting a feeble old man previously exonerated of being a guard at Treblinka? Contained within this question is an odd neutrality on the matter of Demjanjuk’s having served at a different death camp—and the implication that there’s a statute of limitations on genocide. Nor is it particularly relevant that, as is often argued, that at such an advanced age Demjanjuk is no “threat,” and thus unlikely to foment a pogrom in suburban Cleveland. The prosecutors aren’t likely motivated by a desire to reform, but to punish. Those who insist upon bringing Demjanjuk before a court, Buchanan argues, are motivated by the “same satanic brew of hate and revenge that drove another innocent Man up Calvary that first Good Friday 2,000 years ago.” (It is perhaps the one instance in which Richard Nixon is a useful character witness. In 1992, Nixon told his then-assistant Monica Crowley that Buchanan was “so extreme” that he’s “over there with the nuts.”)

Surprisingly, though, after his acquittal on charges that he served as a guard at Treblinka—significant and compelling evidence suggested that, while a member of the SS, prosecutors placed him at the wrong camp—the Israeli government expressed little interested in prosecuting Demjanjuk for his role as guard at Sobibor, arguing that too much time had passed to make a convincing case. According to Sereny, Israel only agreed to the first trial after three conditions were met: “the accused had to be healthy and reasonably young, indictable for murder, and credible witnesses had to be available.”

In Germany, newspapers across the political spectrum are broadly supportive of the new prosecution. As the left-leaning Süddeutsche Zeitung recently editorialized, “the German judicial system has been so terribly slow and forgiving” of fascist—and, it should be added, communist—war criminals and that this will likely be “the last Nazi trial.” And as such, let’s make this one count.

Does this suggest that the prosecution of a cog, a bit player like Demjanjuk, serves only to satiate a German quest for historical absolution? Buchanan argues that “[h]e is to serve as the sacrificial lamb whose blood washes away the stain of Germany’s sins.” This is undeniably a factor, though Buchanan also claims that it’s impossible for Germany to prosecute a homegrown war criminal, “[b]ecause the Germans voted an amnesty for themselves in 1969.” This would come as welcome news to the family of 90-year-old former Wehrmacht officer Josef Scheungraber, a German national currently on trial in Munich for the 1944 “reprisal” murder of 14 Italian civilians. (Buchanan, it seems, is referring to a 1968 modification of Article 50 of the German penal code requiring prosecutors prove that that defendants acted out of “base motivation”—i.e. anti-Semitism—in the commission of war crimes.)

If convicted—and simply establishing Demjanjuk’s voluntary employment in a Nazi death camp is significant—divining the motives of those who agitated for his deportation and prosecution will be interesting only to historians, who will weigh the role of “German guilt” in this final flesh-and-blood confrontation with its hideous past, and the conspiracy cranks, who will track the hidden hand of “international Jewry.”

For the victims like Thomas Blatt, a former inmate at Sobibor, such debates are inconsequential: “I don’t care if he goes to prison or not—the trial is what matters to me. I want the truth. The world should find out how it was at Sobibor.”

Michael C. Moynihan is a senior editor at Reason magazine.

Michael Moynihan, Tablet Magazine’s “Righteous Gentile” columnist, is the cultural news editor of Newsweek/The Daily Beast.