Sowing Hatred in Venezuela

A prominent challenger to President Hugo Chávez isn’t Jewish, but his roots are. That’s enough for the regime.

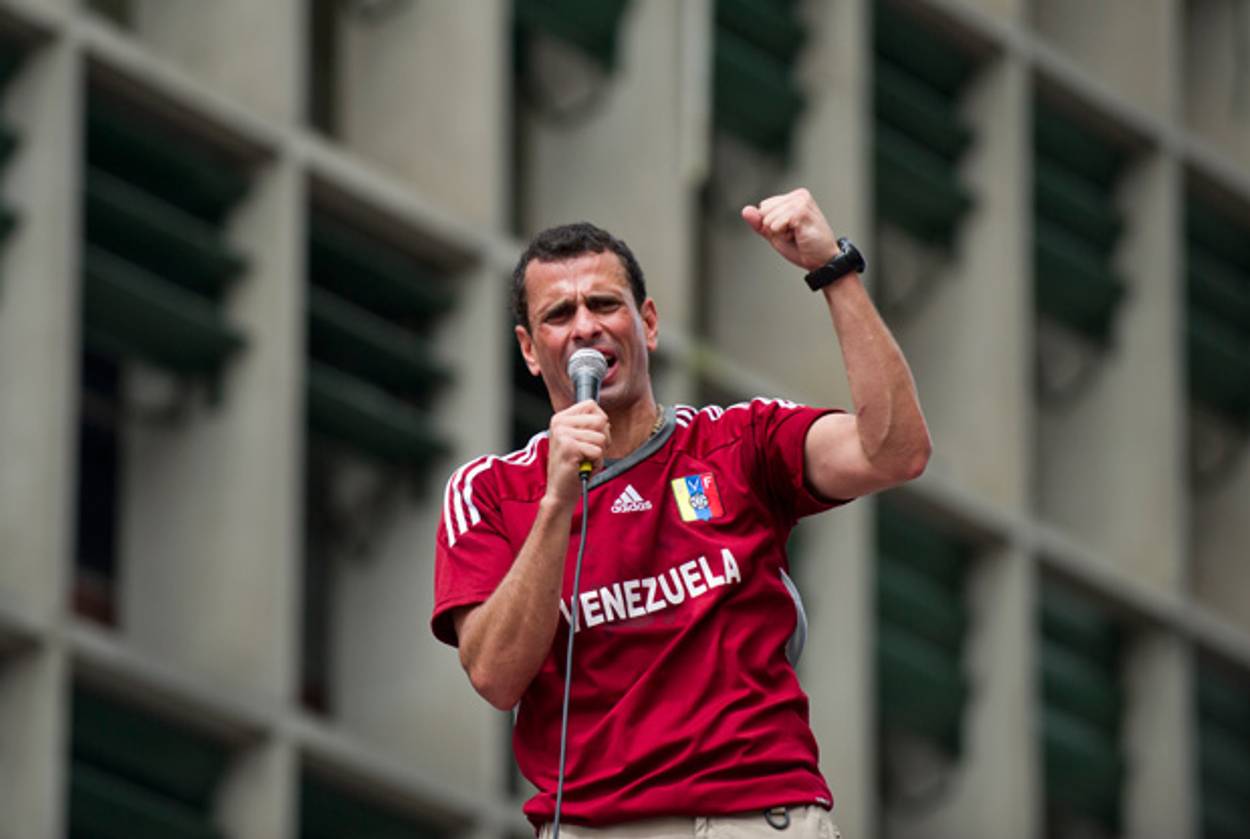

Four days ago, Henrique Capriles, the youthful governor of Miranda state in Venezuela, launched his campaign to rid the country of Hugo Chávez at the presidential election scheduled for October this year. Joined by thousands of supporters, the newly minted candidate led a six-mile procession through the capital city, Caracas. Their final destination was the office of the national election board, where Capriles formally registered his candidacy.

The march showcased Capriles, whose Jewish origins have been mercilessly attacked by the Chavistas, as the anti-Chávez—not just figuratively, but literally as well. By marching for a long distance over a short space of time, Capriles wanted his fellow Venezuelans to see him as the picture of health, in marked contrast to the ailing Chávez. For more than a year now, Chávez’s physical condition has been subjected to the sort of rolling speculation typically reserved for dictators. Until Saturday, Chávez had released virtually no information about the terminal cancer he is widely believed to be suffering from. Then, one day before the Capriles march, he summoned journalists to his presidential palace to tell them, “I feel very good.” The following day, Chávez held a buoyant election rally of his own.

The rally didn’t disguise the fact that Chávez, who is currently serving his third term as president, has never looked so vulnerable. His failing health is only part of the story; in the six years that have passed since the last election, the country has become mired in poverty, violent crime, and corruption. Fired by the high price of oil, Venezuela’s principle export, Chávez lavished cash on social spending, while the underlying economy suffered from inflation and capital flight. These days, Venezuela looks less like a socialist version of Singapore and more like the Latin American equivalent of Zimbabwe. According to Sammy Eppel, the head of the Human Rights Commission of the Venezuelan Bna’i Brith and a frequent commentator on Venezuelan affairs, not even the 8 million beneficiaries of Chávez’s grandiose social justice programs, who combined make up nearly half of the electorate, can be relied upon to cast their votes for the commandante. Capriles, a moderate leftist who leads a coalition of 30 opposition parties, plans to capitalize on this uncertainty.

Yet in a country like Venezuela, where infrequent elections are the only glimmer of democratic hope in the face of a regime that has acquired the core features of a dictatorship, no opposition candidate can be considered a shoo-in. Most polls show Chávez comfortably in front; nonetheless, the regime has several options up its sleeve in the event of a Capriles victory.

There is the prospect of Chavismo without Chávez, whereby a handpicked successor continues the path of the revolution; Chávez’s daughter and brother are spoken of as possible candidates, as is current Foreign Minister Nicolás Maduro. There is the constantly swirling talk of a military coup, a measure that the country’s generals, who are immersed in drug trafficking worth hundreds of millions of dollars, might decide is a preferable alternative to being arrested and imprisoned by a democratic government. In addition, Chávez could follow the example of his close ally Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and simply steal the election. “We do not have an electoral arbiter,” I was told by Diego Arria, a leading opposition figure and former Venezuelan U.N. ambassador. “We have what I call the ‘Ministry of Elections of Mr. Chávez.’ And they will do whatever they have to in order to prevent a defeat.”

Lastly, and arguably most importantly, Chávez can marshal his extraordinary media and propaganda resources to pound away at Capriles’ reputation. Central to that effort is the demonization of Capriles as an agent of capitalism, gringoism, imperialism, and—critically—a concoction of conspiratorial tropes that point to the greatest lurking danger of all: “Zionism,” which for many is interchangeable with “Judaism.” As a recent headline in the weekly pro-Chávez rag Kikiriki so elegantly put it, “We are fucked if the Jews come to power.”

***

Henrique Capriles may be a devout Catholic, but he comes from Jewish stock. His mother’s family, the Radonskis, were Jewish émigrés from Poland; his great-grandparents were exterminated in the Treblinka concentration camp; and his grandmother spent nearly two years in the beleaguered Warsaw Ghetto. His father, meanwhile, is descended from the long-established Sephardic community on the Caribbean island of Curaçao. Although Capriles has expressed pride in his background, his family never considered themselves part of Venezuela’s diminutive Jewish community. For the purposes of the regime’s propaganda operation, that brooks no difference.

“The best opposition candidate for Chávez is Capriles,” said Sammy Eppel. “Any other candidate, like Diego Arria, would be different—they couldn’t call him a Zionist. But Capriles fits the bill perfectly.” Eppel points out that the cartoons lampooning Capriles in the Chávez-controlled press invariably feature him wearing a Star of David. And because Capriles is unmarried, the Chavistas can’t resist a homophobic swipe either; in many of these same cartoons, he wears a pair of pink shorts.

“There is no anti-Semitic tradition in Venezuelan culture,” asserts Daniel Duquenal, one of the few dissident bloggers in Venezuela. “But Chávez has been systematically developing anti-Semitism in Venezuela.” All of which is eerily reminiscent of “anti-Semitism without Jews,” a phenomenon that emerged in the eastern bloc and in certain Arab countries following the Second World War. Absent a numerically significant Jewish community, anti-Semitism becomes a largely ideological weapon, designed to stoke fears of shadowy outside forces hatching conspiracies.

What, if any, are the potential gains of such a strategy for Chávez? Diego Arria is adamant that while the regime is unambiguously anti-Semitic, its deployment of anti-Semitic discourse will yield few concrete advantages. “Capriles says, ‘I am a mariano, a follower of the Virgin Mary,’ ” says Arria, who attended school with Capriles’ father. “People in Venezuela do not see him as a Jew. I don’t believe that an anti-Semitic campaign will have much impact on the Venezuelan population.”

Contrastingly, Duquenal argues that the value of anti-Semitism lies outside the domestic arena, pointing to Chávez’s geopolitical calculations. Chávez has actively promoted a close commercial and political relationship with the mullahs in Iran. He has established himself as a loyal ally of Syrian dictator Bashar al Assad going so far as to dispatch 300,000 tons of diesel, which arrived on a Venezuelan freighter, La Negra Hipolita, two days before the gruesome massacre in the town of Houla. Last week, Chávez ended another long period out of public view by publicly welcoming a delegation from Belarus sent by that country’s dictator, Alexander Lukashenko, who plans to visit Caracas personally in a few weeks from now.

“Anti-Semitism has been created artificially because Chávez wants to align himself with radical regimes against the United States,” Duquenal said. “That’s the only logical explanation I can find for why Chavismo has deliberately decided to become an anti-Semitic political movement.”

Both Duquenal and Sammy Eppel point to the enduring influence over Chávez of Norberto Ceresole, the late Argentinian fascist intellectual with whom he struck up a friendship. “Ceresole was like the parrot on Chávez’s shoulder,” Eppel says. “He wanted bring the far left and the far right together, and he persuaded Chávez that he was the man to do that.” Once Chávez, following Ceresole, aligned the dregs of fascism with those of communism, anti-Semitism became the ideological glue binding the Chavismo model of government, in which the relationship between the leader and his people is central, unencumbered by pesky interferences like an independent judiciary. It is no accident, Eppel believes, that the first chapter of a book by Ceresole extolling this model was titled “The Jewish Problem.”

Occasionally, the vulgar rhetoric of Venezuelan anti-Semitism has strayed into physical attacks. In January 2009, an armed gang stormed the Tiferet Israel synagogue in Caracas, spraying choice slogans like “Damned Israel, Death!” on its walls. This particular theme echoed a speech that Chávez delivered in China in 2006, in which he claimed that Israel had “done something similar to what Hitler did, possibly worse, against half the world.”

In a monograph published in April, “Chávez, The Left and The Jews,” the academics Claudio Lomnitz and Rafael Sanchez contend that in Chávez’s Venezuela, “politics and political life represent a kind of hand-to-hand combat between the ‘people,’ united by ‘love,’ and its enemies, united by hatred—the ‘ire’ that Ceresole imputes to the Jews.” Such cloyingly emotional, anti-rational politics are the perfect breeding ground for the fantasies about Jewish power that Chávez has actively promoted and that will doubtless be wheeled out against Capriles as the election approaches.

***

For Venezuela’s remaining Jews, these anti-Semitic fantasies underline their own harsh reality. Diego Arria describes the community as having been “decimated”; under Chávez, its numbers have declined from a height of 30,000 to just 9,000. Moreover, the Chavista bureaucracy seemingly delights in placing obstacles in the community’s way. Just before Passover this year, the interior ministry announced that extra sanitary permits would be needed if the importation of matzo, the unleavened bread consumed during the festival, was to be approved. And when the Jewish community needs to make official representations, its leaders are directed to the Foreign Ministry—proof, Sammy Eppel asserts, that the regime fundamentally regards Jews as aliens, not Venezuelan citizens.

All the indicators are that Venezuelan Jews will continue to leave the country, heading for more benign destinations like Colombia, Mexico, and Miami. “They are an integrated Latin community, so they go where there is a Latin culture,” says Eppel. “This isn’t a Polish shtetl.” It is possible that a Capriles victory will stem the tide of emigration, but even then, the years of destruction wrought by Chávez will remain a powerful push factor for Jews and non-Jews alike.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Ben Cohen, a former BBC producer, is a writer based in New York who publishes frequently on Jewish and international affairs. His Twitter feed is @BenCohenOpinion.

Ben Cohen, a former BBC producer, is a writer based in New York who publishes frequently on Jewish and international affairs. His Twitter feed is @BenCohenOpinion.