The New One-State Solution

On the cusp of this month’s Israeli election, powerful Likud politicians push for annexation of the West Bank

Three years ago, when Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu gave a speech at Bar Ilan University calling for “a demilitarized Palestinian state” alongside the Jewish state, it was hailed as a historic moment for the newly elected leader: For the first time ever, one of the Oslo Accords’ harshest critics publicly affirmed his belief in two states for two nations. Whether or not that conviction is sincere has been called into question ever since. Bibi’s detractors say he has done little to pursue such a vision and question the wisdom of his decision to build in the E1 area east of Jerusalem, a retaliatory move following the Palestinians’ U.N. bid—and one that some say would not allow for the creation of a territorially contiguous Palestinian state.

But never before have Netanyahu and his Likud Party seemed less serious about a two-state solution than they have in the run-up to this month’s election.

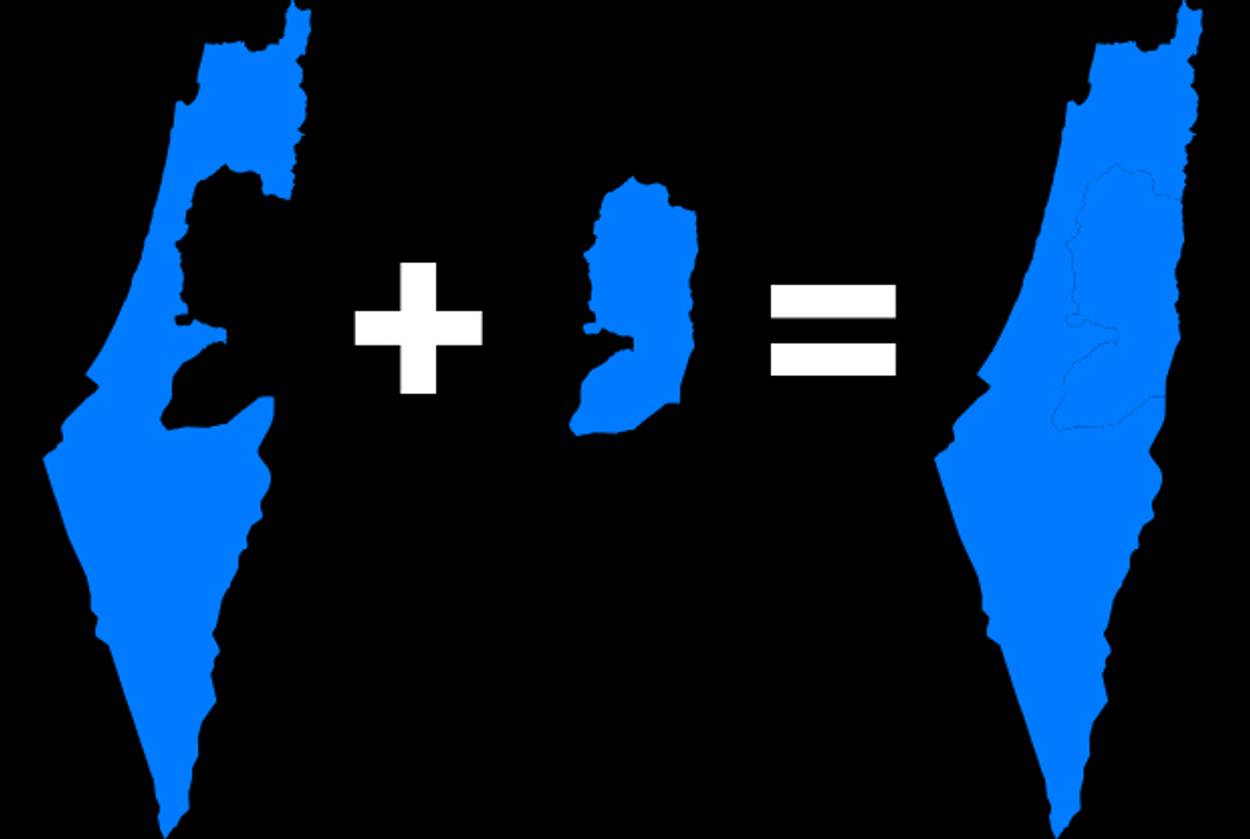

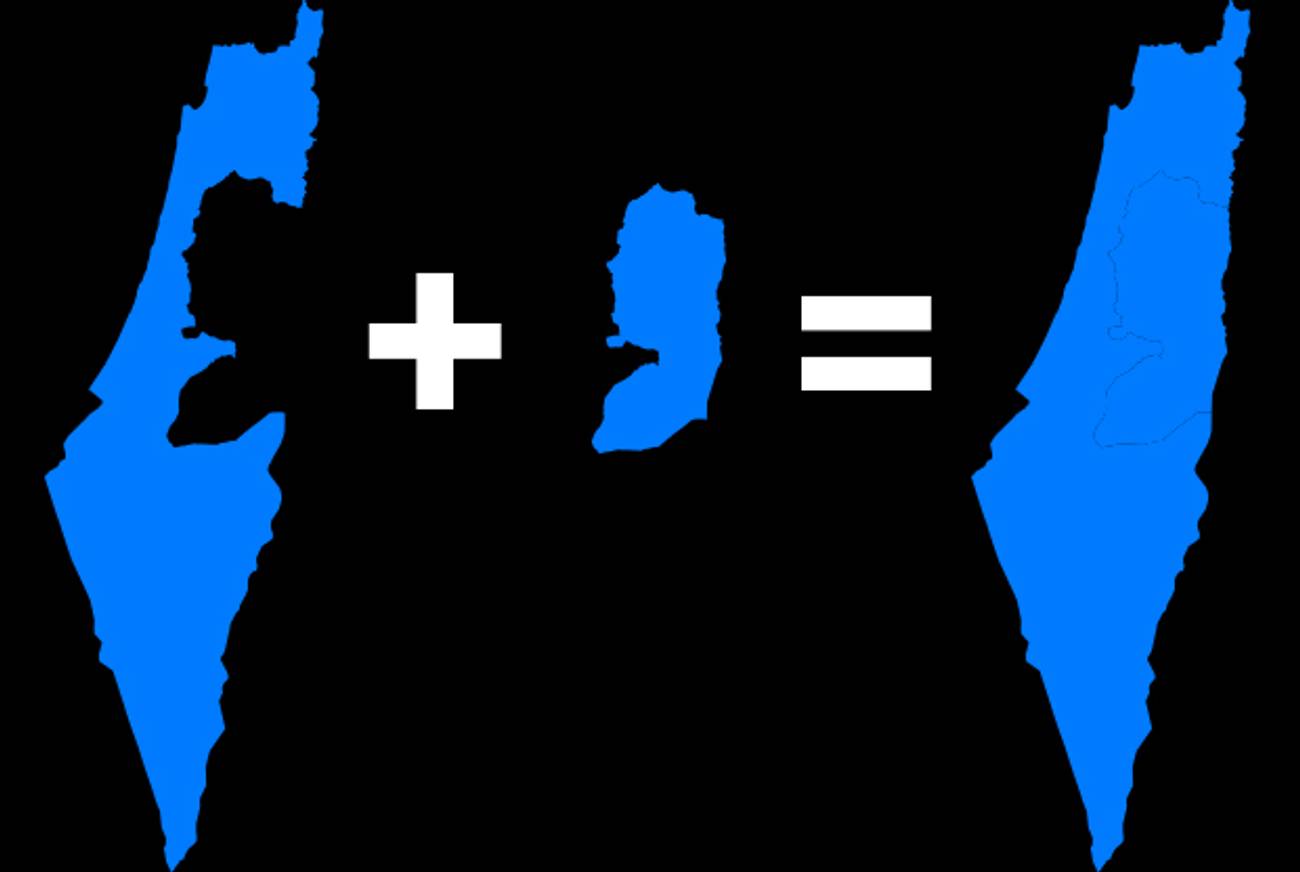

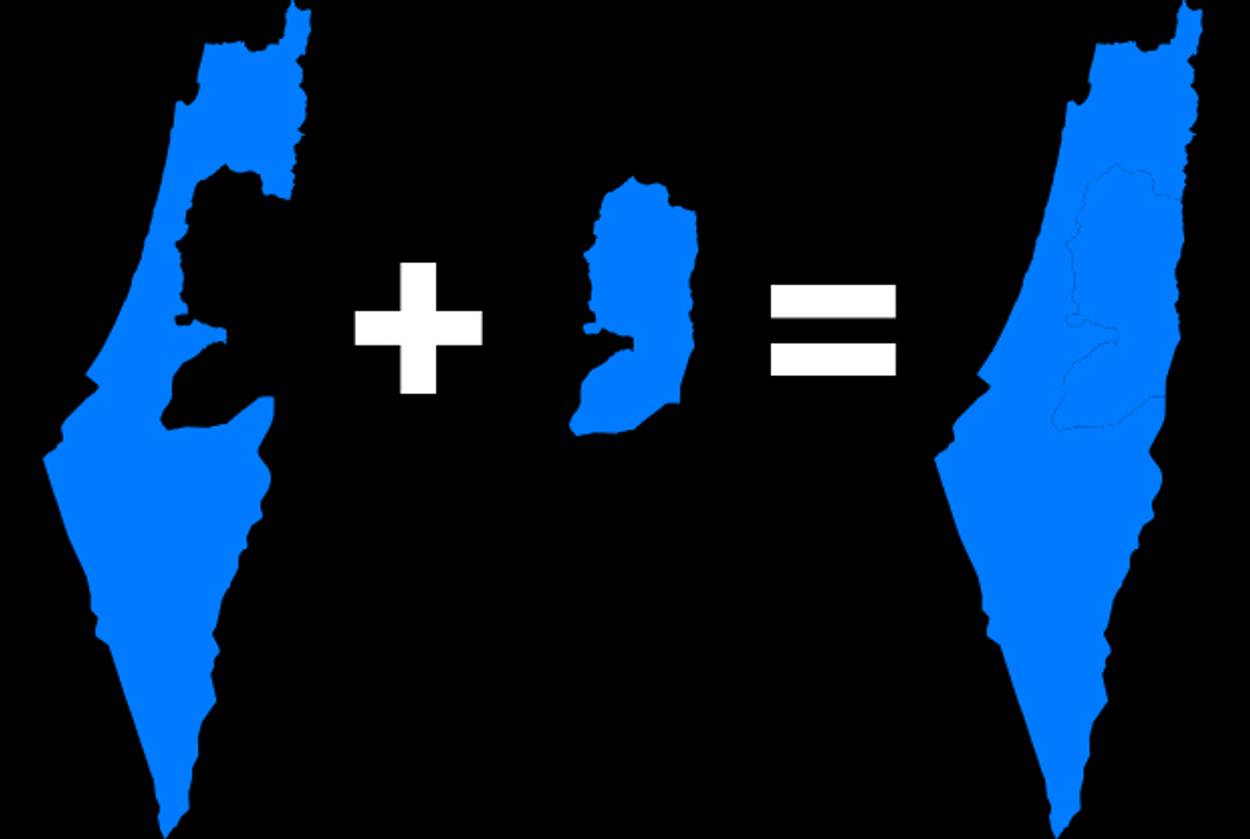

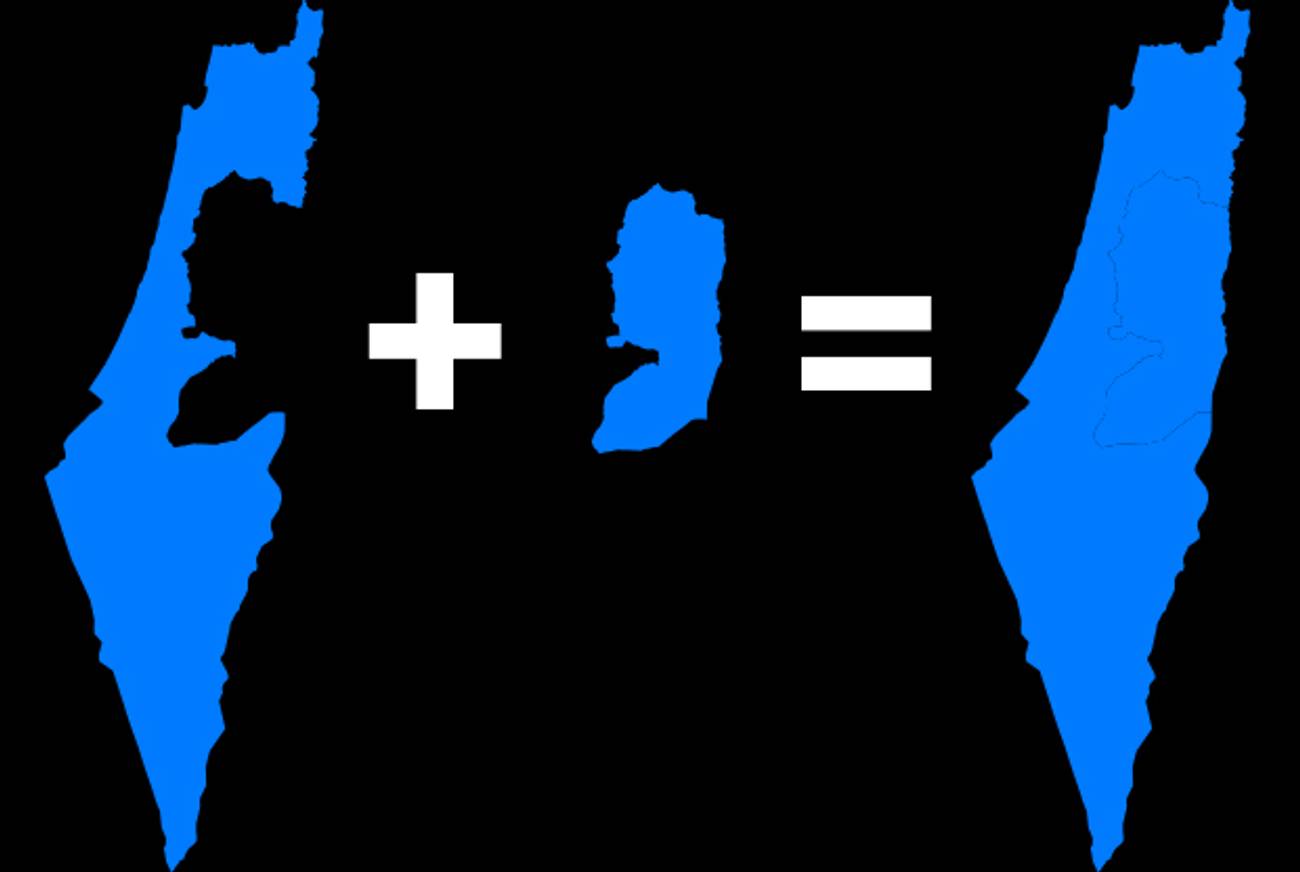

Not five years ago, annexation of the West Bank—the expansion of Israeli sovereignty that would ensure a Jewish state on both sides of the 1967 “green line”—was a radical idea even among the Israeli right. The conventional wisdom was that the continued occupation of the West Bank would quickly result in Jews outnumbered by Arabs between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River, and Israel would be forced to choose between being a democratic state or a Jewish one. No longer. Annexation is quickly gaining steam among powerful precincts of the Israeli right, including high-ranking members of the Knesset who see no contradiction between Israel formally applying its sovereignty over millions of Arabs and remaining a democracy.

Last week, hundreds of Israelis gathered at a conference center in Jerusalem’s religious Bayit Ve’gan neighborhood for the Third Annual Conference for the Application of Israeli Sovereignty over Judea and Samaria, which included appearances by prominent Likud politicians. Annexation is not part of the official Likud-Beiteinu party platform, of course—but neither is any other clear alternative. And the fact that senior members of Israel’s ruling party would go on the record three weeks before the election in support of such a revolutionary plan says much about the traction that these ideas are gaining.

***

Virtually all of the attendees at last week’s conference were Orthodox Jews of the national-religious stream; many of them native English speakers. The evening was organized by Women in Green, a group established in 1993 to protest the Oslo Accords (and whose name is a play on the anti-occupation Women in Black). Women in Green has long advocated for Israeli sovereignty over the West Bank, but they are no longer part of the political avant garde. The Levy report, published last summer and named for former Supreme Court Justice Edmund Levy, who headed its committee, concluded that the Jews, as the indigenous people of the biblical land of Israel, have clear historical rights there. According to the report, but contrary to what most experts believe, the Israeli presence in the West Bank—settlements included—is legal under international law. Thus Israel, its commitments to the peace process notwithstanding, is free to annex the territory. While the government has yet to officially adopt the report’s more radical recommendations—Netanyahu has preferred to implement sections dealing with planning and building procedures—the conference was dedicated to bringing them to life.

The idea sounds simple on paper: The West Bank has been under Israeli military rule for over 45 years, complicating life for both Israeli settlers and Palestinians. For starters, Israeli legal jurisdiction applies only to the Israeli citizens living there, and its application is entirely subject to the discretion of the IDF Central Command. (For example, the IDF had to recognize the Ariel College’s transformation into a university for that change to actually take effect.) Right now, Palestinians are subject to both Israeli military law and to the law of the Palestinian authority; applying full Israeli sovereignty would subject Palestinians to Israeli civilian law. But most important for some on the Israeli right, the West Bank is an integral part of the historic Land of Israel: For it to become a Palestinian state is unthinkable for both religious and defense reasons. Therefore, Israel must apply its sovereignty there, formally annexing the West Bank as it did both East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights and affording the Palestinians something between full citizenship and limited residency.

Netanyahu didn’t attend the conference in Bayit Ve’gan, but there was a strong contingent of Likud Party members, with Information and Diaspora Minister Yuli Edelstein, and MKs Yariv Levin and Zeev Elkin, the outgoing coalition whip, all prominently featured. The three are wildly popular politicians in their party and ranked highly in the recent primaries. In their speeches, Elkin and Levin both advocated use of what they called the “salami technique”—a plan to affect Israeli sovereignty on the ground gradually—slice-by-slice, starting with current Israeli settlements and expanding later on to include areas densely populated by Palestinians, the Jordan river valley, and even Gaza. Elkin even offered a tip of the hat to the late Palestine Liberation Organization Chairman Yasser Arafat, who stated that the Oslo Accords were just another step in his phased plan to bring about Israel’s eventual destruction. “It’s time,” Elkin said, “that Israel takes the same tack. Stop conceding and go on the offensive, step by step.”

These three are not the only Likud politicians with these views. MKs Tzipi Hotovely and Miri Regev, the highest-ranking women in the party, are both ardent supporters of the cause. Regev unsuccessfully attempted to pass an annexation law last year; Hotovely recently insisted that Netanyahu’s support of a two-state solution was pure tactics and that he didn’t mean a word. But the most prominent supporter of annexation is Knesset Speaker Reuven Rivlin. A front-runner for Israel’s presidency when Shimon Peres steps down, the longtime Likud MK has publicly advocated a one-state solution numerous times.

Likud’s right-ward shift, evidenced by the ouster of its more moderate MKs and subsequent merger with Avigdor Lieberman’s Yisrael Beiteinu party, has also been accelerated by the rising popularity of Naftali Bennett’s HaBayit HaYehudi party, the new reincarnation of the historic National Religious Orthodox party. Bennett—a young, successful high-tech entrepreneur who was a major in the IDF’s special forces—has managed to revive a decaying party by making it an attractive option for nonreligious people who would traditionally vote Likud. Bennett’s party stands a fair chance of becoming second-largest in the next Knesset—and annexation figures prominently on his platform.

Bennett’s “partial annexation” plan calls for Israeli sovereignty over Area C, which comprises 60 percent of the West Bank and includes all of the Jewish settlements and their environs. Whereas Areas A and B are Palestinian-run, C is currently under full Israeli control. Bennett’s annexation plan is attractive to many because it focuses exclusively not on messianic ideology, but on security and paints a rosy picture of a comfortable Palestinian autonomy after the annexation. (Elyakim Haetzni, a former member of Knesset and one of the pioneers of the settlement movement, advocates a similar plan but admitted at the conference that it would place the Palestinians in a choke hold, effectively allowing only for limited self-administration.)

Rabbi Eli Ben Dahan, however, No. 4 on Bennett’s ticket and until recently the head of Israel’s rabbinical courts, used very different rhetoric while describing his own vision. Gone was the focus on security; in came the numerous biblical decrees affording the Promised Land to the people of Israel and forbidding concessions. “That there are minorities in this land, Arabs who call themselves Palestinians, is nothing new,” he said. When Joshua led the Israelites into Canaan, he too encountered minorities—and they were allowed to stay, Ben Dahan summarized, if they accepted Jewish rule and quit idolatry. “That should be the policy towards the Palestinians,” he argued.

***

None of the speakers at the conference seemed particularly perturbed by what the global response to such actions might be. In fact, many argued that this would be the least of Israel’s problems. “The real problem,” said Moshe Feiglin, who ran the Zu Artzeinu (“This Is Our Land”) group that violently protested the peace process in the ’90s and is set to win a Likud Knesset seat later this month, “is with those Israelis who just don’t understand that this land belongs to us—and only to us. Once they do, applying sovereignty will be easy.”

Edelstein, the diaspora minister, went so far as to suggest that applying sovereignty would strengthen Israel’s standing abroad by depriving foreign diplomats of the ability to suggest that Israel doesn’t seriously believe it will stay in the West Bank in the long term. He also proposed using different terminology: not the “West Bank” or the “territories” but Judea and Samaria to emphasize the biblical connection. “ ‘Settlements’ sounds colonial. We should say ‘Jewish communities,’ ” he said. “Then no one would say ‘Jewish communities’ should be evacuated—it sounds anti-Semitic.”

All concede that the problem is, at its core, one of demography, and the conference’s closing panel discussion was devoted to the status of the Arabs after sovereignty. When the application of sovereignty started gaining headway on the right several years ago, its original proponents, such as Rivlin and former Minister of Defense Moshe Arens, favored bestowing Israeli citizenship unto the entire Palestine population. They accused the left—with its constant talk of the demographic threat and good fences making good neighbors—of segregationist racism along the lines of Avigdor Lieberman’s plan for land swaps that would leave Israel free of Arabs and Palestine free of Jews. The humane thing to do, these early proponents asserted, would be to annex the entire territory, with Arabs remaining in place and receiving full citizenship rights. As a result, the sovereignty movement was often accused of post-Zionism, favoring the sanctification of the land while sacrificing Israel’s Jewish character. (The movement, frequently relying on the work of contrarian researchers, claimed that there was no real demographic threat to speak of, and that the numbers floated by the left were wildly exaggerated.)

But now it seems that the idealistic belief, held by Rivlin and others, that there could be a Jewish liberal democracy on both sides of the green line has taken a dark turn. Indeed, a strain of casual racism pervaded the discussions at last week’s conference. Haetzni, the pioneer of the settler movement, said he would be willing to allow for a limited Palestinian autonomy, but stressed the need for clear separation, so as “not to let them mix with us, not to let them debase us.” MK Aryeh Eldad of Otzma LeYisrael (“Strong Israel”) spoke optimistically of the Hashemite Kingdom’s coming collapse as part of the Arab Spring. Once that happens, a Palestinian government in Jordan is guaranteed, and the Arab population in the West Bank is welcome to stay in their villages but vote only for the Jordanian parliament. Or, better yet, to move there.

While the Kahanist idea of forcibly “transferring” out the Arab population was never mentioned, both Dr. Martin Sherman of the Israel Institute for Strategic Studies and Moshe Feiglin argued that, with generous enough offers, the vast majority of Palestinians would be perfectly content to leave voluntarily. Feiglin pointed out that the money that Israel currently spends on the separation fence, policing the local population in the West Bank, and stocking up on Iron Dome missiles (“the costs of the peace process,” he called such expenses) could be used instead for “evacuation encouragement grants”—half a million dollars each—to be awarded to Palestinian families who would then leave to other countries. There’s no other way around this, Sherman, who grew up in South Africa, said. Two states in such a small geographical territory are simply not feasible.

Is this alliance between messianic ideology and secular nationalism—expressed as annexation—gaining the same traction in the public sphere as it has among political elites? Despite the popularity of HaBayit HaYehudi and Likud-Beiteinu, recent polls show that two thirds of Israelis still support a two-state solution with strong security measures, despite skepticism regarding its prospects, while only 20 percent oppose it. Even among right-wing voters, a majority say they would support such a plan. That disparity between public sentiment and electoral prospects could be explained by the classic Israeli maxim that only the right wing can pull off a peace deal. But on the cusp of such an important election, it seems odd—and therefore telling—that these ideas should be getting such an unprecedented airing in the Israeli mainstream.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Tal Kra-Oz is a writer based in Tel Aviv.

Tal Kra-Oz is a writer based in Tel Aviv.