Iran To Investigate JCC Bombing

Why is Argentina letting Iran examine the 1994 AMIA bombing in Buenos Aires, a crime Hezbollah surely committed?

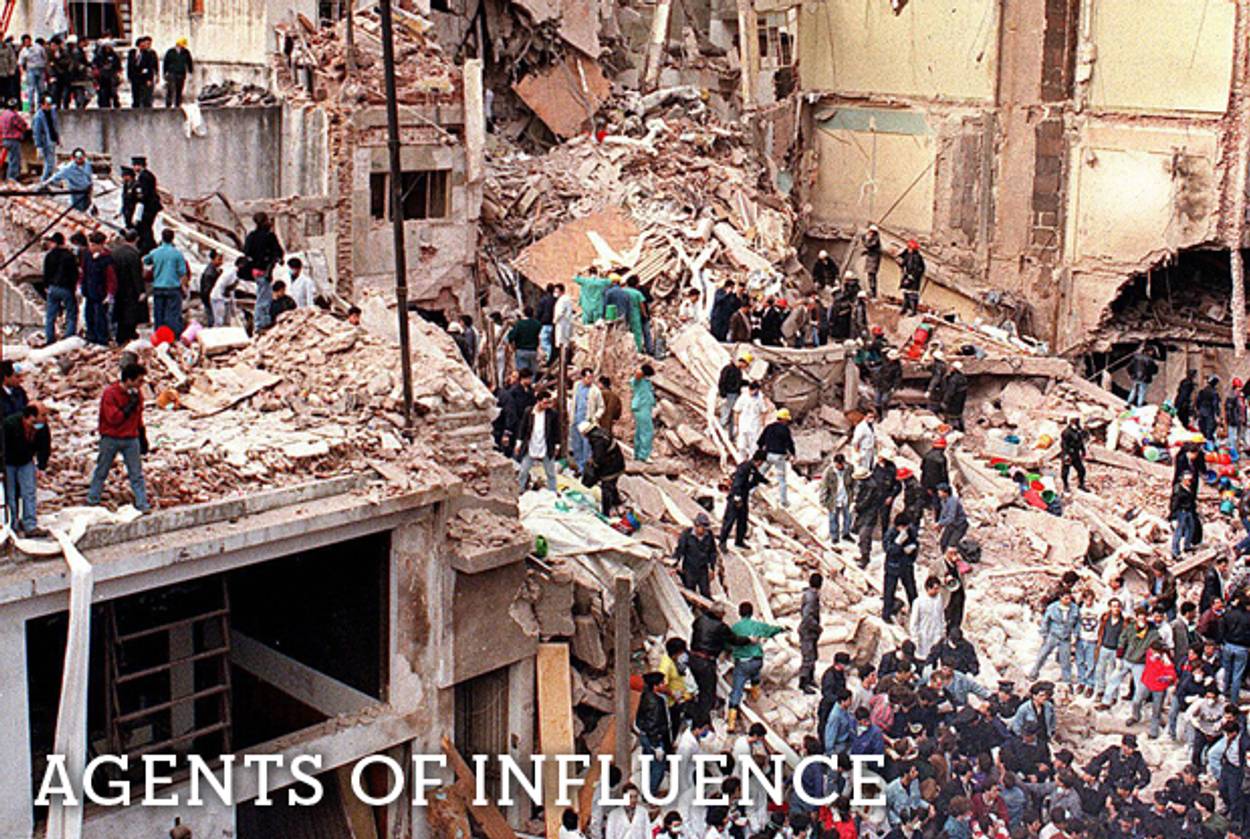

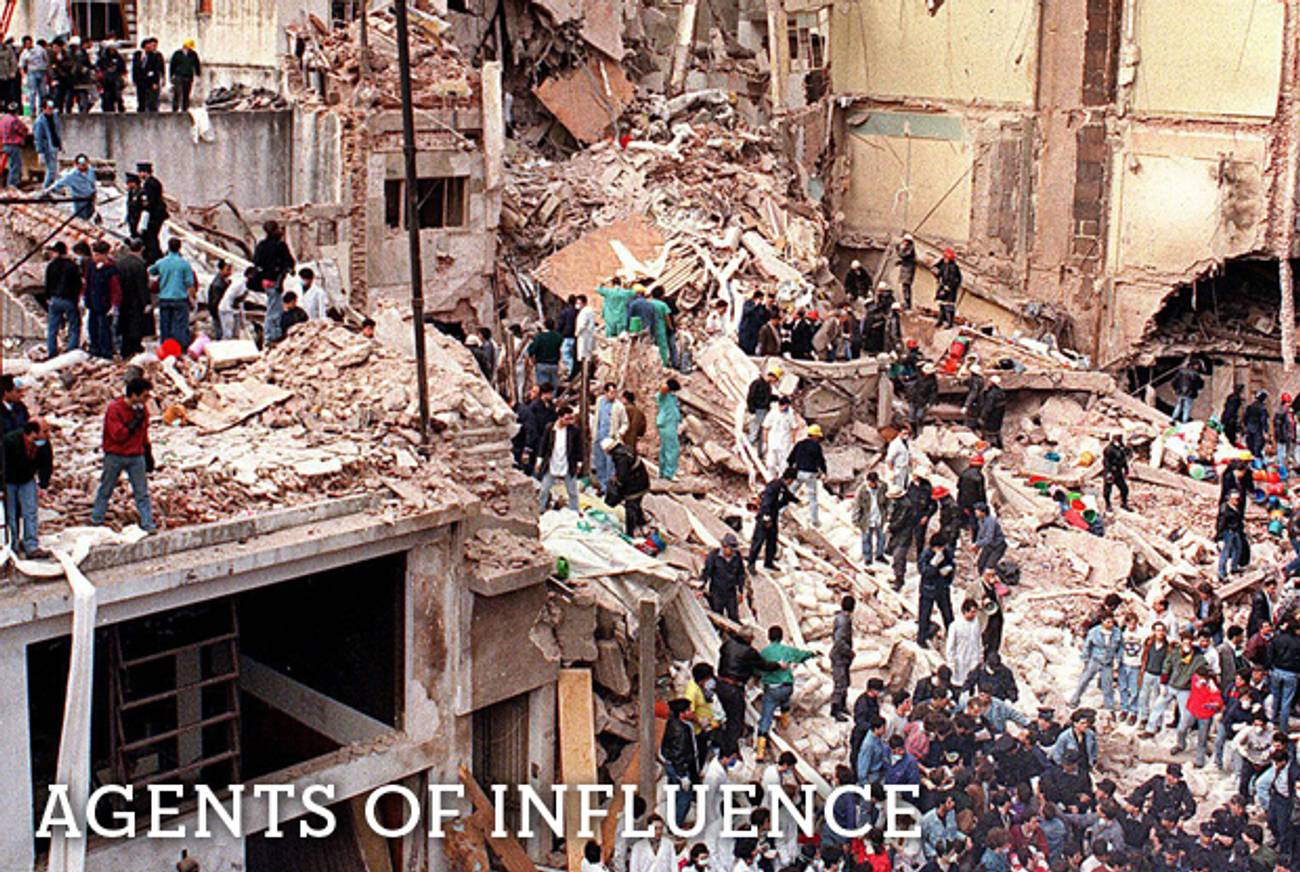

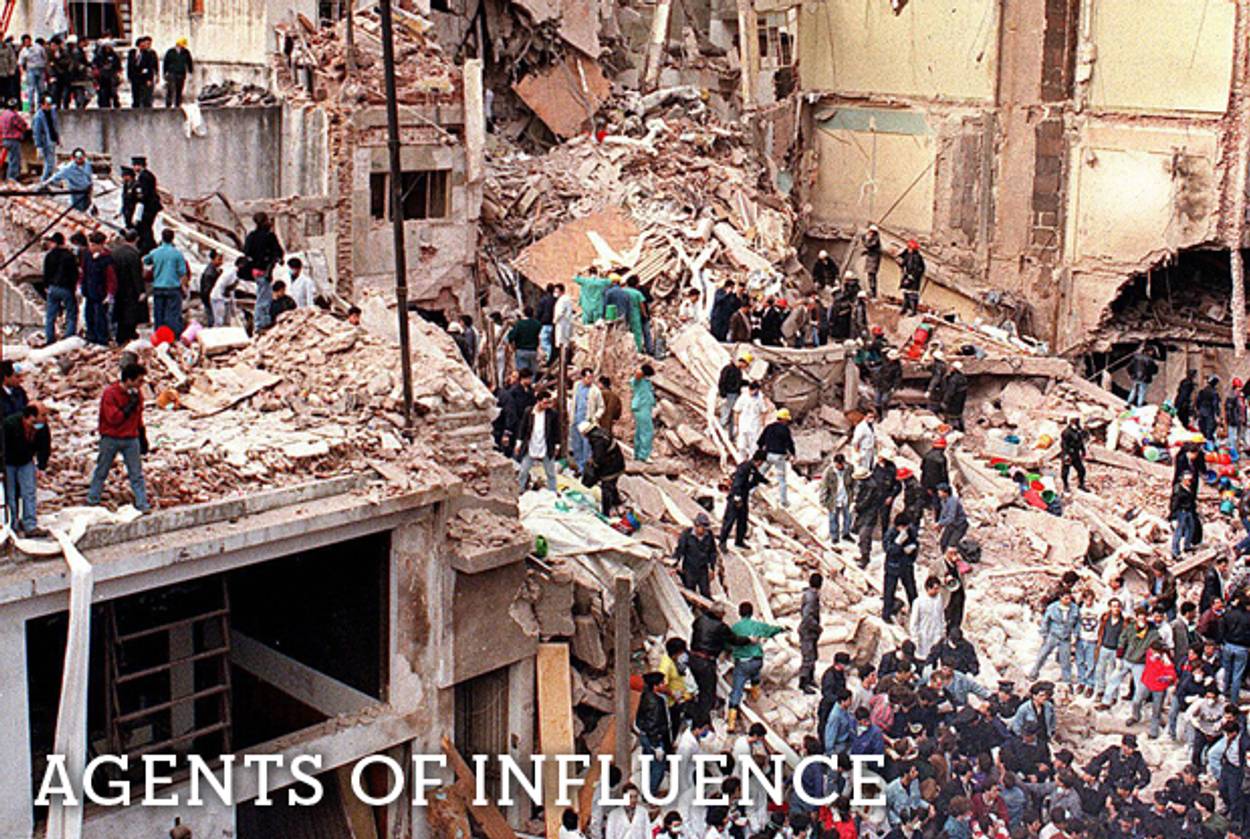

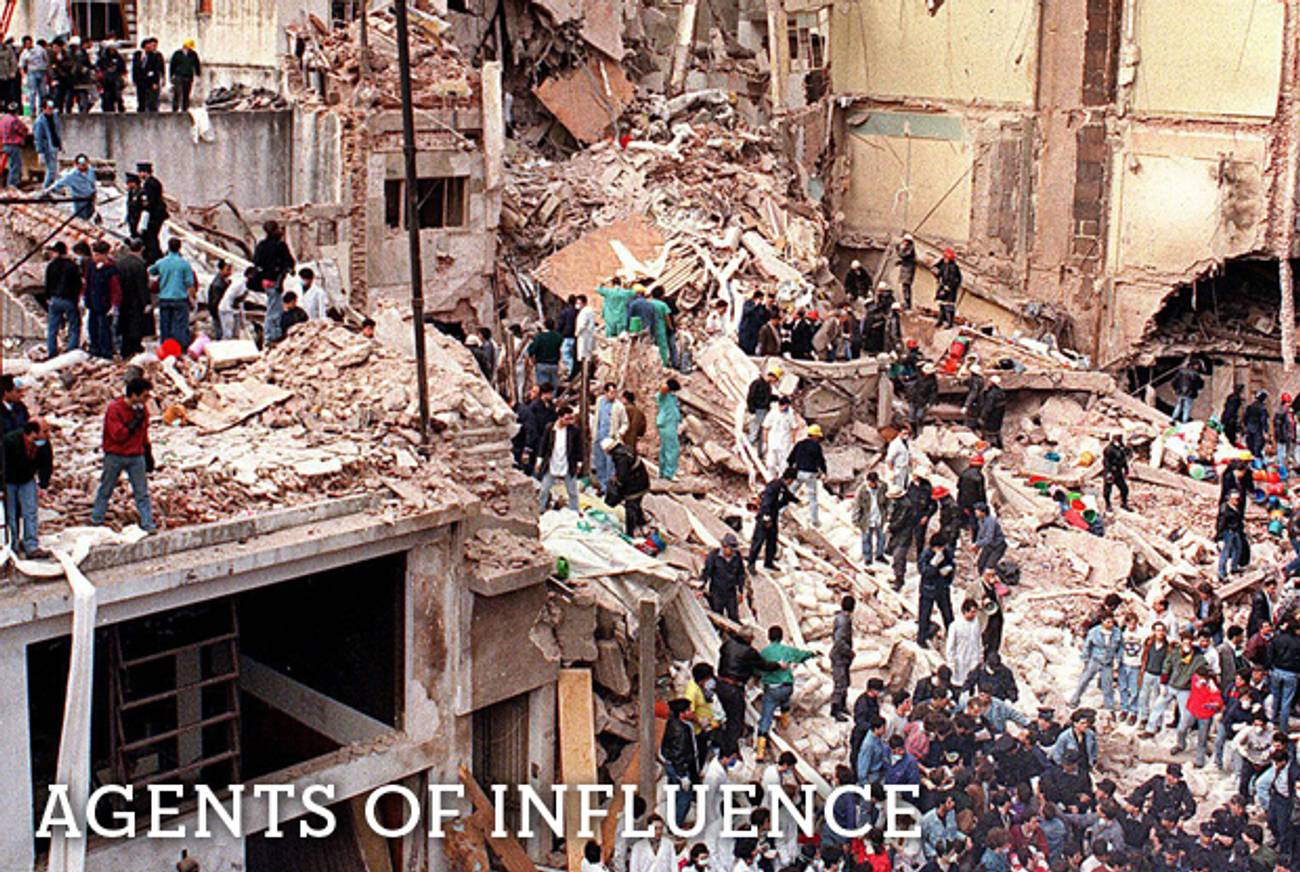

On July 18, 1994, a massive car bombing leveled the Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina in Buenos Aires, killing 85 people and wounding hundreds. That there have been no arrests after almost 20 years, that the initial investigations foundered and were marred by incompetence and corruption, is what led Argentina’s former president, the late Nestor Kirchner, to call the case a “national disgrace.” Apparently that message didn’t get through to his widow, current President Cristina Kirchner, who late last month announced that Argentina was partnering with the Islamic Republic of Iran—the country allegedly responsible for the attack, and one in the business of murdering Jews— to establish an independent international “truth commission” tasked with examining evidence and recommending how to proceed “based on the laws and regulations of both countries.”

The timing of the announcement (International Holocaust Day) and the manner of its delivery (Kirchner’s Facebook page and Twitter feed) has only added insult to injury. “Historic,” Kirchner called the agreement, “because never will we allow the AMIA tragedy to be used as a chess piece in a game of faraway geopolitical interests,” she added with no apparent sense of irony. The reality is that the purpose of the agreement is to bury the case entirely. It’s not a truth commission, but a deal: In exchange for Buenos Aires handing Tehran a diplomatic coup, the Iranians will do their part to help rescue a moribund Argentinian economy through investment and trade.

Israel’s Deputy Foreign Minister Danny Ayalon likened the formation of the truth committee to “inviting the murderer to participate in the murder investigation.” It’s a fair assessment. From the outset, the Iranian regime was believed to have been responsible for the AMIA Jewish community center attack, as well as the 1992 bombing of the Israeli embassy in Buenos Aires, which killed 29 and injured 242.

But it wasn’t until October 2006, when Argentinian special prosecutors officially charged that it had been carried out by a team of Hezbollah operatives, including the late head of the terrorist group’s external operations unit, Imad Mughniyeh, under the direction of the highest authorities in Tehran. An Argentinian court issued arrest warrants for Mughniyeh as well as six senior Iranian figures, among them former President Ali Rafsanjani and current Defense Minister Ahmad Vahidi. According to the report that the special prosecutors presented the judge in the case, a group called the Special Affairs Committee, which includes Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and Rafsanjani, convened in the Iranian city of Mashad on Aug. 14, 1993, to approve the attack.

Iran, of course, has long denied any involvement in the AMIA attack, and its intense diplomatic efforts to shirk responsibility seem to have finally paid off. Mutual commercial interests and shared ideological sympathies have brought Argentina and Iran closer than ever before—and this so-called truth committee is only the latest evidence of the increasingly close alliance.

***

First, there’s the pragmatic reason for the Iran-Argentina relationship. The Argentinian economy is foundering. Outstanding World Bank and Paris Club debts have cut off Argentina’s access to international credit markets, and Iran, under heavy U.S. and E.U. sanctions, needs trading partners. “The Argentinian government is desperate for money,” Pablo Kleinman, a Latin America policy analyst, told me. And with the value of Iran’s currency plummeting due to sanctions, it is coming to rely more heavily on Argentina’s agricultural exports, which help keep food prices down within Iran. “Argentina is making overtures to a number of third-world countries besides Iran,” Kleinman said, “especially energy rich-dictatorships, like Angola and Algeria, to get them to invest.”

In addition to economic cooperation, the Iran-Argentina agreement also represents the intersection of ideological convictions. Where anti-Semitism was once a prominent feature of Argentina’s right-wing politics, now it’s a part of the left. And the Argentinian left, like much of Latin America, interprets Iran’s shadow war against the United States and Israel as a pillar of left-wing resistance to neo-imperialist hegemony. In other words: Terrorist attacks on Jews are a necessary, if sometimes regrettable, phase in the progressive struggle against the West.

Tilting to the left has proved to be a very astute political move by the Kirchners. “They had a very small support base when they got to power in 2003,” Kleinman told me over the phone from Buenos Aires. “They figured out if they catered to the left they had a base ready to support them, even though they have no history of supporting leftist causes before they won the presidency. But now, the hard left is a pillar of support for this government, and it backs this deal with Iran.”

What’s more, the growing alliance reportedly enjoys the patronage of high-level figures, most notably Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez and Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. “It was Chávez who advised Kirchner to patch up relations with Iran, if she wanted to pave the way for Iranian investment,” said Kleinman. Indeed, Cristina Kirchner is also personally indebted to Chávez, Tehran’s premier interlocutor in Latin America, since he is believed to have donated large sums bankrolling her election campaigns.

***

But one of the most disturbing elements of these latest developments is that Buenos Aires’ point-man in these negotiations with Iran is a Jew who carries a name famous in human rights circles: Foreign Minister Héctor Timerman, son of the respected journalist Jacobo Timerman, who was imprisoned and tortured by Argentina’s military junta during the late 1970s for his criticism of the regime’s human rights violations during the so-called Dirty War against its opponents.

His 59-year-old son Héctor has an impressive résumé: Timerman, also a human rights activist, started his career as a journalist and then served as Argentina’s consul general in New York from 2004-2007. Later, he was ambassador to Washington. He was chosen for those posts, argued veteran Argentine reporter Pepe Eliaschev, “because as a Jew he was thought to be exactly the right person who would open doors with the Jewish community and business circles in the United States.”

In December, a month before the truth commission was announced, Timerman was reaching out to Argentina’s Jewish community, explaining the ostensible purpose of meeting with his Iranian counterpart Ali Akbar Salehi at the United Nations in September. “The only business that we have in this case is for Iran to deliver the accused to justice,” said Timerman. “There isn’t any other interest. The government and the relatives are on the same path, which is to find those responsible [for the attack] and obtain an Argentine judiciary sentence against them.”

According to the journalist Eliaschev, Timerman planted the seeds for the deal three years ago, when, shortly after he was named foreign minister, he visited Aleppo, Syria, to meet with Salehi, in consultations sponsored by Assad. Eliaschev based his report for the Argentinian newspaper Perfil on what he described as a leaked Iranian document. Timerman denied the story and called Eliaschev a “pseudojournalist.” “He denounced me because he got caught,” Eliaschev told me in a phone interview. Eliaschev knew Timerman’s father, Jacobo, who had even been his editor for a time, and like his father, Héctor Timerman “is a well-known advocate of human rights and progressivism.”

It is curious to imagine what his father might have thought of a human rights advocate who is negotiating over corpses with a regime every bit as bloody as Argentina’s military junta. In a Tablet profile of Timerman in 2010, he explained that his father “strongly disapproved of those Jews who stayed quiet in order not to draw the regime’s wrath.”

His son, however, was tasked with the job of selling the deal with Iran to the Jewish community, including families of the victims of the AMIA bombing. Polls show that more than 80 percent of Argentina’s 200,000-strong Jewish community is against the deal. Last week, Timerman held a meeting in Buenos Aires where he made promises to the community, explaining that the commission would not replace the ongoing investigation by the Argentinian government.

“We are trying to find a way to advance the cause, which has gone 19 years without being resolved,” Timerman said in a press conference after his meeting with the community and relatives of the AMIA victims. “We’ve made significant progress, where for the first time the Iranian suspects will be brought before an Argentine judge.” Of course they won’t—not Rafsanjani, not Vahidi, nor any of the others. The Iranians have managed to dodge justice for the AMIA bombing for almost 18 years. Now, thanks to the Argentinian government, they can breathe easily.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Lee Smith is the author of The Consequences of Syria.

Lee Smith is the author of The Permanent Coup: How Enemies Foreign and Domestic Targeted the American President (2020).