Turkey Hawks Bird as Israeli Mossad Spy Beacon, Ruffles Feathers

Bird-brained conspiracy theories keep a tenacious foothold in the Arab Middle East, where science lags behind the West

Last week, Turkish authorities released a kestrel after a thorough investigation showed it was not spying for Israel. It’s a good thing the Turks were 100 percent sure because, to hear Israel’s neighbors tell it, the Mossad often employs birds to do its dirty work. One vulture believed to be spying for Israel was detained in Saudi Arabia in 2011, another was apprehended in Sudan in December 2012, and the Turks believed they were also targeted previously, in May 2012, by a European bee-eater.

Like the kestrel, the other birds were all tagged with markers identifying them as research subjects, such as the study of migratory patterns. The very signs then that should have made plain they were part of scientific studies were instead taken as evidence that they had been enchanted by some secret Israeli spell.

The Mossad kestrel is only the latest creature to walk out of the Israeli bestiary, a compendium of God’s creatures lifted from nature and, the story goes, put to work by Jews against Muslims and Arabs. Perhaps the most famous of all Israel’s animal operatives was the shark who attacked German tourists off the coast of Sinai in the winter of 2010, presumably for the purpose of damaging the Egyptian tourism industry—a feat the Egyptians accomplished over the last two and a half years on their own, thanks to the chaos that they’ve unleashed on their now bloody streets, and without any animal collaborators.

If these shaggy dog conspiracy tales are sure to get a laugh from Western readers, it’s worth keeping in mind that magical fantasies seeing Jews as uncanny manipulators of the natural world partake of the same paranoid and sinister narrative structure that authored the blood libel.

There’s nothing funny about it for the Turks, either. Once upon a time, Turkey and Israel enjoyed a strategic relationship. Among other benefits that came from this alliance, Turkey purchased arms from Israel, including drones, of which Israel is the world’s largest exporter. Ankara wanted the unmanned aerial vehicles, among other reasons, to gather intelligence on and then target the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, which has waged a bloody insurgency against Turkey since 1984. After Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan cashiered the alliance as well as the defense contracts with Israel, the Turks turned to their own domestic industry for unmanned aerial vehicles. The problem, however, was that Turkish drones were unable to beat the nasty habit of crashing.

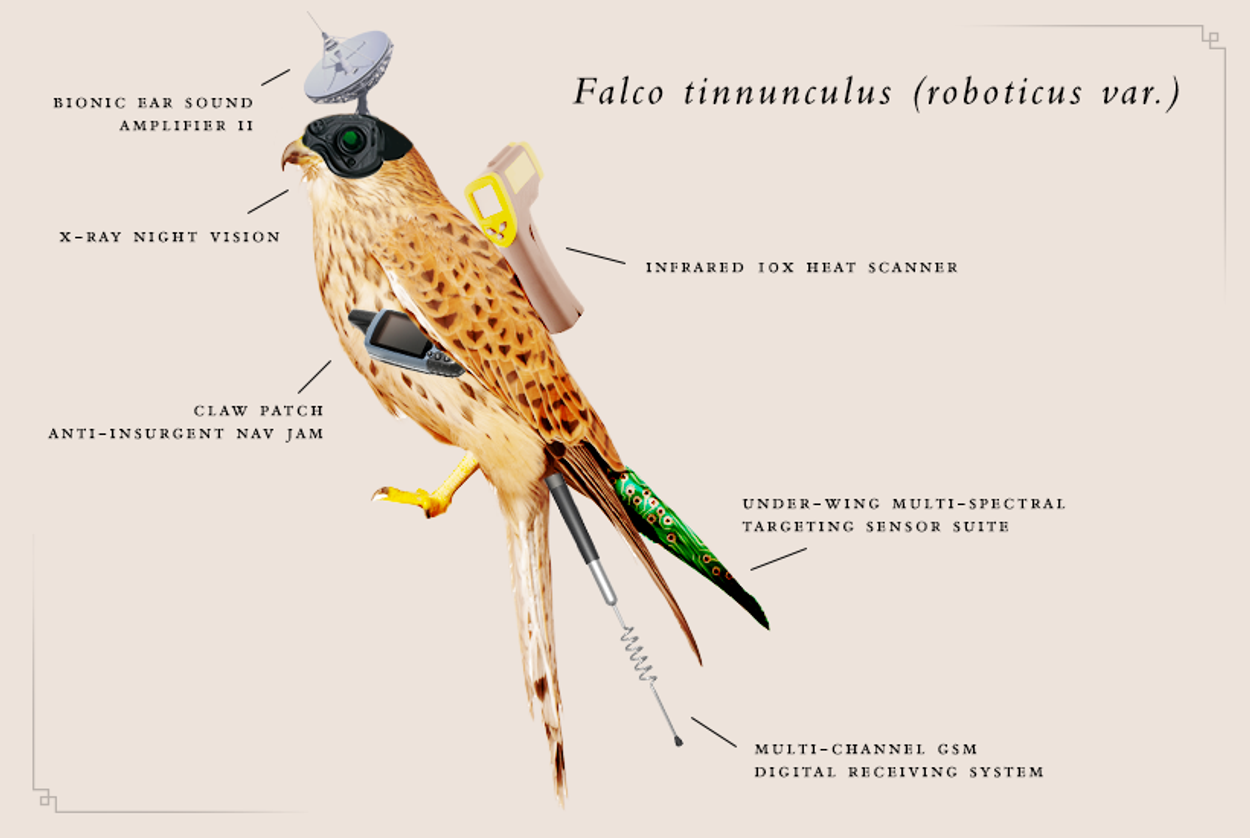

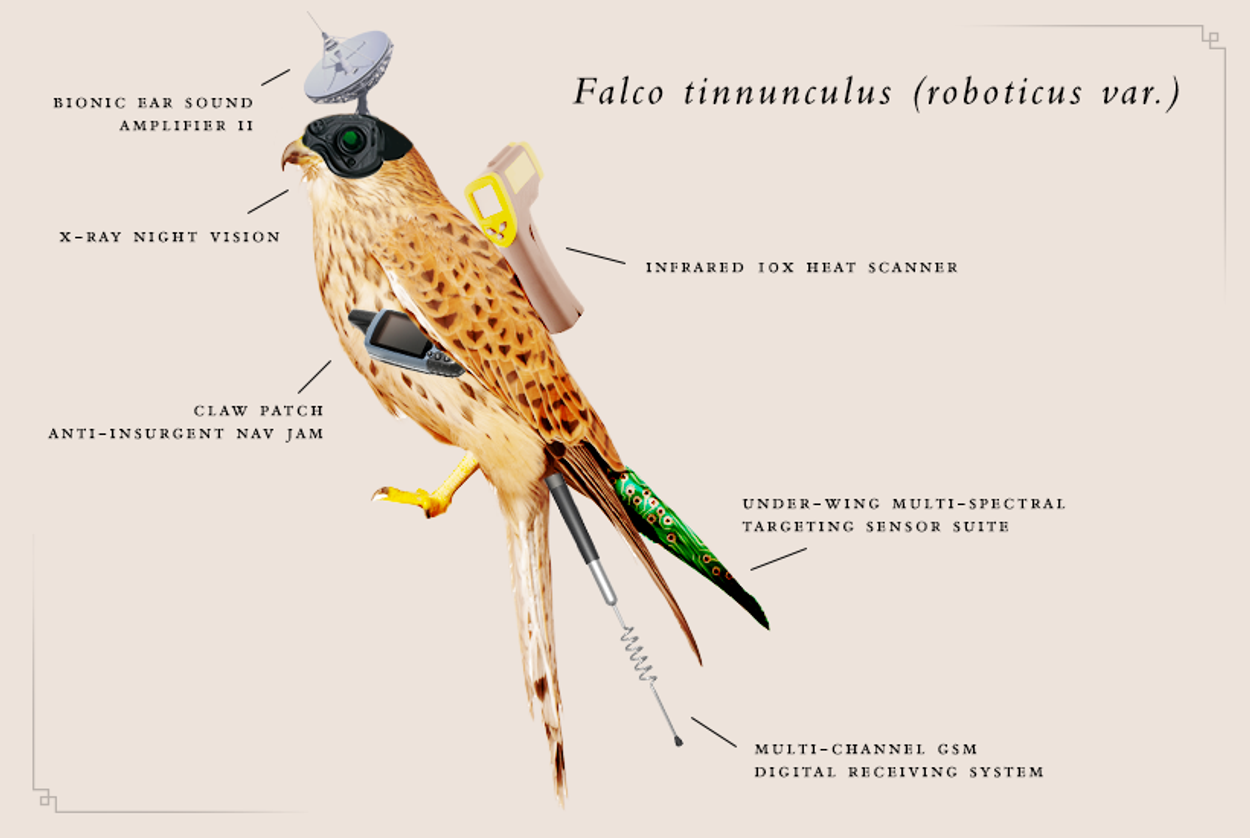

To say that Ankara has failed to master the science of flight is an understatement. The fact that Turkish authorities believed the bird last week was effectively a new kind of Israeli drone and only released it back into the wild after an X-ray showed it was carrying no surveillance equipment suggests that some in Turkey are incapable of distinguishing science from magic.

Of course some commentators reason that, even accounting for the appetite many Arabs and Muslims have for pre-scientific conspiracy theories, Israeli spies really do pull off some fantastic stunts. However, it’s useful to remember that if Israel, for instance, blew up Imad Mughniyeh in the middle of Damascus, the Mossad’s assassination of Hamas commander Mahmoud al-Mabhouh was captured on video cameras in Dubai. That is, the Israelis also make mistakes—they’re talented and proficient, but they’re people, not supermen, or warlocks and witches.

Still, hundreds of millions of Middle Eastern, African, and Asian Muslims can only understand the world as a large Harry Potter set in which they will never be among the initiates, the spell-casters. Paradoxically, the reason that this horrifying recognition boils to the surface only occasionally is the stunning success and availability of Western science and technology. It is because cell phones, for instance, are so cheap that even the tens of millions of Egyptians who, without government subsidies and foreign aid, couldn’t afford to put food on their plate can purchase technology designed in Palo Alto and Herzilya. Otherwise, the divide between a society that makes and one that simply consumes would be clear for all to see.

You can say that there is no such thing as Western science and technology, but that’s just a Western perspective based on hard-won Western values, like empiricism—either F=MA or it doesn’t. What is verifiable is true not just for so-called Westerners but is true for all men in all times. But this may not be how the vast majority of the Muslim world understands reality.

The 19th-century Muslim reform movement that arose after Napoleon’s 1798 conquest of Egypt was impressed with Western science—specifically the military technology that allowed French troops to overrun the lands of Islam so easily. The reformers counseled Muslims to make use of the science, medicine, and technology that the Westerners brought—but at all costs to avoid the Western values, like free thought, that had made those technological advances possible. In other words, Muslims were forever condemned to the role of eternal consumer, end-user, and never a producer. Perhaps their consolation is that, like servants, Westerners will make it for them anyway.

Two hundred years later, the United Nations’ 2003 Human Development Report on the Arab World, “Building a Knowledge Society,” delivered the bill. “Despite the presence of significant human capital in the region,” the paper explains, “disabling constraints hamper the acquisition, diffusion, and production of knowledge in Arab societies.”

“Between 1980 and 2000,” writes Hillel Ofek in The New Atlantis, “Korea granted 16,328 patents, while nine Arab countries, including Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the U.A.E., granted a combined total of only 370, many of them registered by foreigners. A study in 1989 found that in one year, the United States published 10,481 scientific papers that were frequently cited, while the entire Arab world published only four.”

According to Pakistani physics professor Pervez Amirali Hoodbhoy, the 57 Organization of Islamic Congress “countries have 8.5 scientists, engineers, and technicians per 1,000 population, compared with a world average of 40.7, and 139.3 for countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Forty-six Muslim countries contributed 1.17 percent of the world’s science literature, whereas 1.66 percent came from India alone and 1.48 percent from Spain. Twenty Arab countries contributed 0.55 percent, compared with 0.89 percent by Israel alone.”

Typically, commentators note that since the Muslim world used to excel in science and technology, there is no reason that it can’t catch up today. The problem is that it’s slipping further behind—and fast. Fifty years ago the gap was costly, but today the price for not understanding science and innovation has increased exponentially. Consider, for instance, the favorite theme of the 19th-century Muslim reformers and rulers—military might. In June 1967, it took Israel six days to defeat the combined Arab armies, including Egypt’s. Despite more than 30 years and many billions of dollars of U.S. military aid, Egypt has fallen further behind the rest of the world, and even its benighted neighbors. Proof can be found in the country’s decision to buy the defective drones that Turkey can’t keep in the air.

Many commentators explain the popular Arab uprisings over the last two and a half years as a consequence of expectations that exceed conditions. This is what happens, Western journalists and analysts reason, when you have millions of college graduates who can only find jobs driving a taxi or pushing a food cart. The reality is that only the rarest of college graduates in Muslim countries is prepared for a Western-style profession.

Cyber-optimists claim that new information technologies will close the gap. Satellite TV, the Internet, Bluetooth will present Muslims with such a clear alternative to their pre-Copernican worldview that they’ll willingly choose to embrace open societies and free markets and become part of the West. But consider some of the ways in which those technologies are used: The Syrian regime used its cell-phone concession to enrich itself. Jihadis set up Internet websites to disseminate propaganda and plan operations. Gulf monarchies like Saudi Arabia and Qatar use their satellite networks not to promote alternative views of the world but to advance the narrow interests of the ruling family. In Egypt, tele-preachers parse passages of the Quran previously impenetrable to much of a population that has a literacy rate of 60 percent to explain why infidels should be killed.

That is, the technology gap isn’t a problem just for the Muslim world, for as the gap grows so does resentment. Consider the region’s most famous research project—the Iranian nuclear program. For decades now this oil-rich Persian Gulf power has been determined to go nuclear—to have a bomb, or as it claims, to provide nuclear energy for its people. Without taking any credit away from the Western intelligence services that have waged inventive clandestine operations to delay the program, including the alleged assassination of nuclear scientists, the reality is that if Iran hasn’t yet mastered the technology, there is something deeply wrong with the scientific culture of the Islamic Republic.

More important, there’s this: Iranians believe that the mastery of this particular field of science—rather than any other field of science, a bustling economy, and world-renowned industries and export goods, or a first-class educational system—will pave the way for Iran’s triumphant re-entry into the community of nations. Not a new microchip, or the cure for cancer, but a nuclear bomb—a weapon of mass destruction, meant to kill tens of thousands of people. A wise man once said never judge a man by his mistakes, but rather by his dreams. In the case of the Muslim Middle East, it is hard not to shudder.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Lee Smith is the author of The Consequences of Syria.

Lee Smith is the author of The Permanent Coup: How Enemies Foreign and Domestic Targeted the American President (2020).