I’ll Miss You, Madiba: One Jewish South African on the Moment Mandela Walked Free

The country and the world came to a standstill then. Can his death inspire a similar momentum for change?

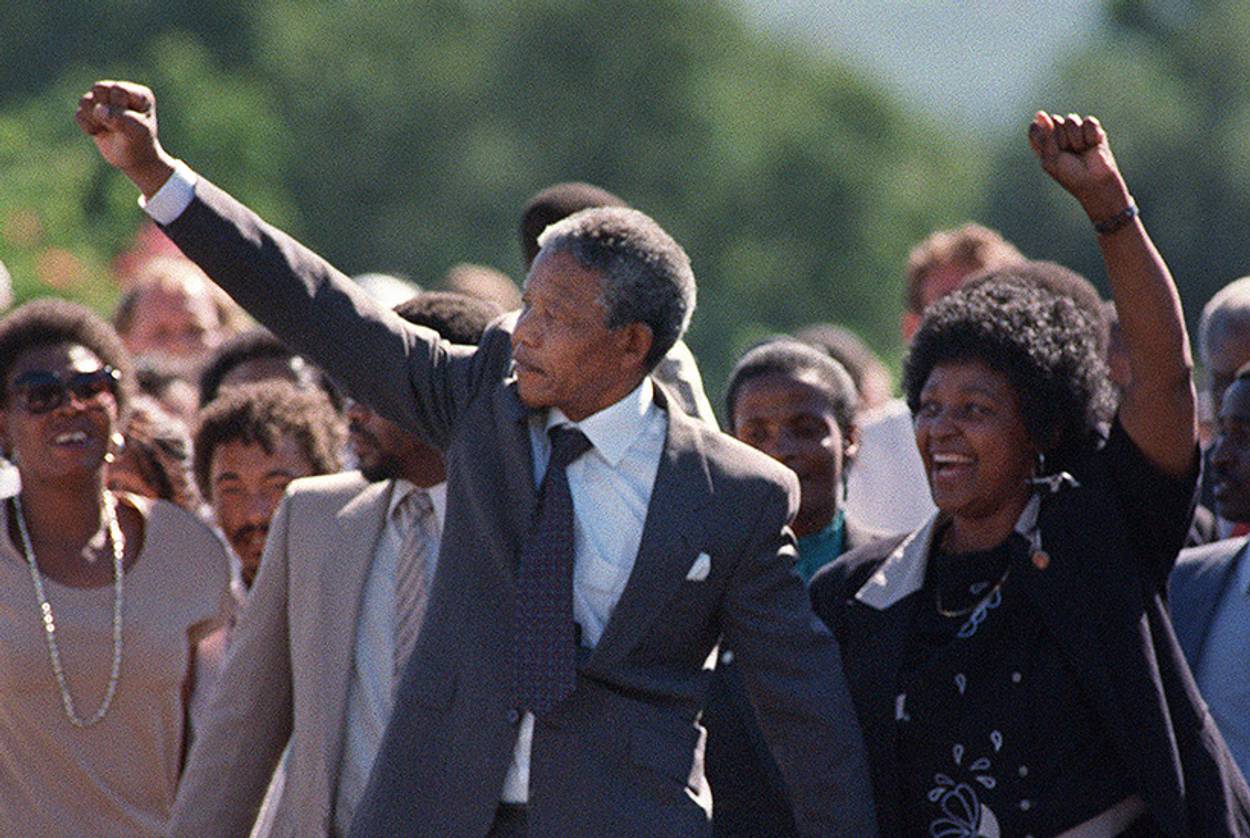

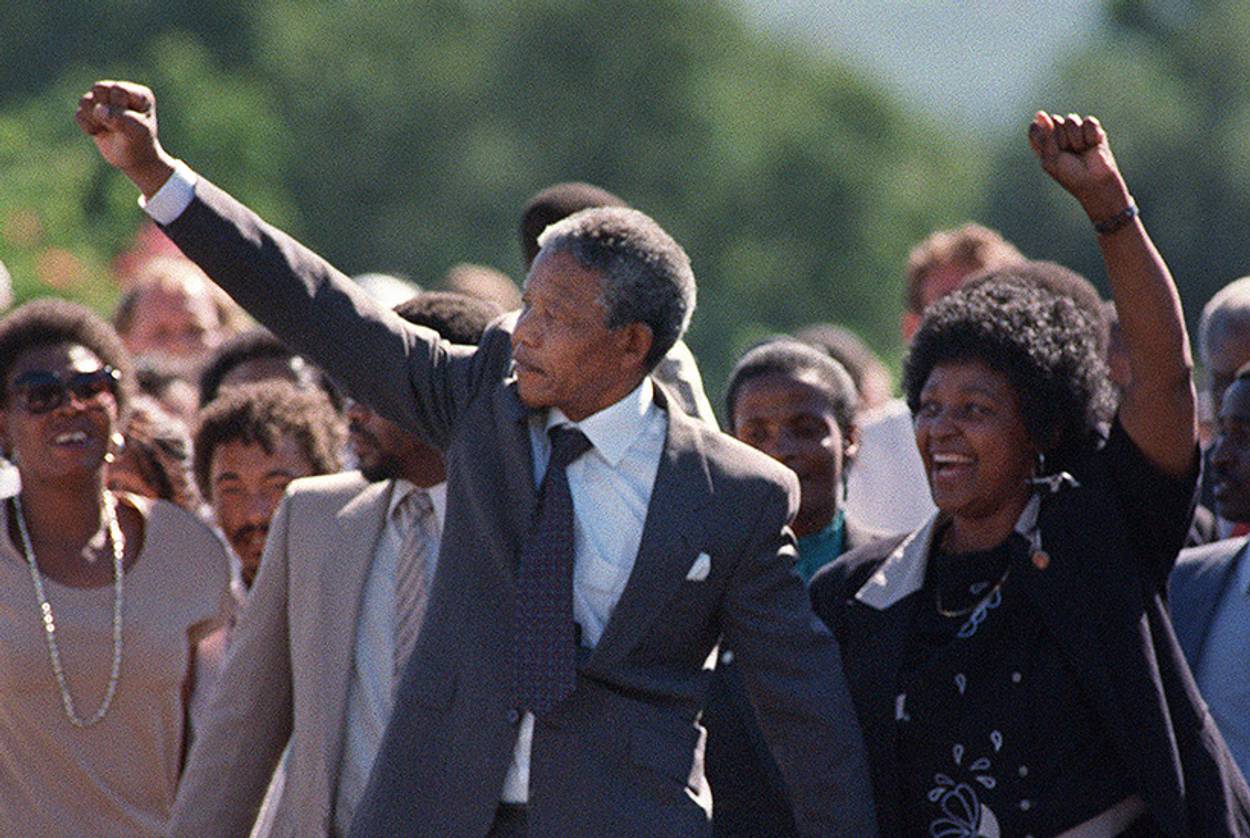

I was a 15-year-old white Jewish schoolboy in the middle of Nowheresville, South Africa, when Nelson Mandela took his long walk to freedom on Feb. 11, 1990. He’d spent 27 years in prison, but I didn’t really know much about what he did to get himself into jail for that long. He certainly wasn’t as famous in my small town as, say, Naas Botha, rugby captain of South Africa’s Springboks. Yet, from his isolated cell on Robben Island, Mandela had come to represent tens of millions of people in South Africa about whom I knew equally little. He was one of the most famous people in the world, and certainly the most powerful man in South Africa. As Mandela left Victor Verster Prison, an event broadcast live around the world, everyone around me watched the TV, waiting to hear what his first words would be. The country, the world, and my little town came to a standstill.

It was probably the first time in the history of South Africa that blacks and whites all stopped what they were doing and did the same thing together: stare at their TV sets, listen to their radios. Perhaps this was the actual historic moment, the silent break in history when masters and slaves alike dropped their tools and lifted their heads to a flickering screen, watching their longstanding power relationship be upended. As I watched Mandela on TV, I wondered if it meant that black kids were going to be allowed into our whites-only school. I wondered what they would be like. Would they play rugby with us, or would they want to play soccer? Could they run faster than us? A more mature version of me would ask if this was, finally, the beginning of South Africa’s redemption.

There was a feeling of change in the air. But not everyone was excited. For some, it was history in the unmaking. A door had been opened into the unknown, and for some, especially in my hometown, it felt like the end of their future, and the sky was about to fall, like the sudden and violent Highveld storms that could break out through a sunny day. The barbarians—I won’t use the K-word tossed around so lightly back then—would be at our gates soon, I heard Afrikaner neighbors in my hometown say.

My hometown. I grew up in Krugersdorp, about an hour west of Johannesburg in what is called the West Rand. For years it was a rough-and-tumble Afrikaner town built on top of deep-level gold, iron, asbestos, and platinum mines. The black townships were on the outskirts, and whites never went anywhere near them. Most of the men in Krugersdorp were either mine bosses, electricians, engineers, plumbers, welders, builders, car mechanics and panel beaters, or they owned hardware stores. Quite a few were ex-military Parabats—members of the 44th Parachute Brigade Special Forces unit, which operated in Angola and South West Africa, now known as Namibia.

It was a hard town: anti-black, anti-Semitic, anti-gay, anti-Greek, anti-Portuguese, anti-anyone who wasn’t a “genuine” Afrikaner. They liked to throw that word around a lot: “Genuine.” They liked Israel—“You guys know how to fight, genuine”—but they hated Jews. It was a town of hard, unhappy men, whose sons played hard, bone-crunching rugby. Krugersdorp folk were into bitterness, boerewors, and brandy—a triple shot of each. Guys would go driving around at night, cruising for a bruising, and God help you if you were at the wrong place at the wrong time.

It was a strange town for a young Jewboy born to Russian parents in Tel Aviv to end up in. My parents left the Soviet Union for Israel in 1969. After 11 years in the Promised Land, my father decided he’d had enough of promises and packed us all up to the next Promised Land—Apartheid South Africa. Perhaps the irony of leaving Jewish persecution in Soviet Russia only to opt for white persecution in South Africa was lost on my father. I don’t know; we never spoke about it. But that’s where I ended up.

Krugersdorp was named after Paul Kruger, the Afrikaner nationalist who led his “Volk” to freedom from the British and established the Transvaal. He was the leader of the Boer resistance against the British in the First Boer War and was president of the South African Republic from 1883 to 1900. Krugersdorp was where Afrikaner commandos gathered to make a blood oath to fight to the bitter end against the British “Rooineks”—rednecks, which was what the Afrikaners called the British, ironically, because anyone else in the world would have called the Afrikaners rednecks, in the American sense of the word. I felt Paul Kruger’s spirit on my bones and knuckles mostly at school; and around town his stern statue stared down at me.

Kruger carved an Afrikaner nation out of the British Empire—a nation that wanted to live separately from the indigenous blacks from whom they took their land. “Separate but equal,” was how they called it, while the rest of the world called it by another name: apartheid. The same Afrikaners then took their freedom and wasted it on establishing a country whose foundations were plunged deep in the thick bile of white superiority—and drenched in rivers of black-red blood. It was a police state where black men would disappear never to be seen or heard from again; or they would “commit suicide” in prison. A country where it was illegal for whites to marry blacks; where a grown black man would call a small white child “master”; and where men like Nelson Mandela were left with no choice but to take up armed struggle against their oppressors. Paul Kruger wanted his people to be free of the British, but he imprisoned the blacks. In time, South Africa became the world’s most reviled pariah state, and Kruger’s people were portrayed in movies like Lethal Weapon just as they were: racist bad guys.

Mandela existed on the complete opposite end of the spectrum of history and myth. He led South Africa’s blacks to freedom from the Afrikaners whom Kruger had liberated from the British. Nelson Mandela wanted South Africa to be free of racism—a Rainbow Nation for all the world to behold and emulate. He knew that for this miracle to work, he could not imprison the whites that had imprisoned the blacks, and him among them. But in Krugersdorp, there were many who didn’t believe Mandela’s message of reconciliation then; and there are still many—whites, blacks, and “coloreds,” as mixed-race South Africans are still known—who have now lost faith in the hope that he offered. South Africa may not have racist legislation anymore, but that doesn’t mean there’s no racism in South Africa today. There is. In all directions.

***

When Mandela walked free, in Krugersdorp and other places like it, there were many “bitter-enders”—those who vowed to fight to the end to keep Afrikaner national aspirations alive. They were spiritually, and physically, prepared for war—a racial bloodbath, Armageddon, a wave of mutilation that was to wash over every white man’s house as revenge for centuries of oppression. A new Battle of Blood River. In those days, like today, South Africa was awash with guns. Everyone had a gun, and even very young boys knew how to point and shoot a .22 rifle with expert skill. There was extreme trepidation and anxiety in my hometown—nobody knew what to expect, and many expected the worst. I think some even welcomed it. These people knew this day would always come, when there would be a final reckoning. Folks were stocking up on guns and ammo. Praise God and pass the ammunition.

They were ultra-nationalists like Clive Derby-Lewis, the man who orchestrated the assassination of South African Communist Party leader Chris Hani in 1993. Derby-Lewis, who through the Hani hit tried to incite a race war and turn back the clock of history, lived down the road from me. The day Hani was shot, the police and army came out en masse and surrounded all the white schools in Krugersdorp, to make sure there were no reprisals. There was terror in the air, but no terror on the ground. The white kids were spared. That was three years after Mandela walked free.

But the day Mandela emerged, the sky didn’t fall. Instead, there was a rain of applause from around the world, a long, sustained and elegant clap, like a gentle Transkei rain, not a thundering Highveld storm. Mandela, born in the Transkei, was the anti-Kruger. His vision was racial equality, not racial purity. There would be reconciliation, but first there had to be truth. When Mandela left prison, he turned to the multitude and said that now was not the time to look back in anger. Racism would not be answered with racism, he said, thus cementing himself in the pantheon of history’s great men; men who ended slavery and exile and gave birth to nations, like Lincoln, like Gandhi, like Ben Gurion. It was the right thing to say at the right time in history, and Mandela was the right man at the right time at the right place. The country would embark on a long, painful process, and there were no guarantees. There was only Mandela’s presence.

Mandela was the first black president of the new South Africa, holding office from 1994 to 1999. But even now, 14 years after he left office, South Africa has still not reached the Promised Land—a land where race plays no part in a person’s chances for success, or where all are equal before the law. Like Moses, Mandela brought his people only as far as he could. There has been no Joshua. All are not equal before the law in the new South Africa; just ask its current president, Jacob Zuma, a man who is the antithesis to Mandela, a man whose moral corruption is only matched by his material excesses. Nothing sickens me more than seeing Zuma sit next to Mandela and smile. Nothing makes me happier than seeing Mandela’s unmoving, stern glare point in Zuma’s direction, as if he were disgusted by him and didn’t care who knew it.

When I think about Mandela’s legacy, I am once again drawn to the town where I grew up. During Kruger’s time, and all through the apartheid years, Krugersdorp was a symbol of white nationalism, of Afrikaner pride and Afrikaner prejudice. These days, Krugersdorp has become a center for poor whites—mostly Afrikaners who have fallen off the wagon, so to speak—living in caravans and white shantytowns. People who have fallen on hard times because the country has moved on without them, because they’re white. Perhaps this is justice. It’s a fact that Mandela didn’t want it to work out this way. The poor whites of Krugersdorp have joined the tens of millions of poor blacks whom the ANC has been unwilling and unable to lift out of the slavery of poverty.

Much of that has to do with the ANC itself: Instead of growing up from its days as a revolutionary resistance movement into a mature, inclusive, and responsible organization, it has monopolized and abused power and become synonymous with corruption and cronyism. Instead of creating a black middle class—the only way forward for South Africa—it has created a black elite in its own image, flush with Mercedes sedans and plush villas built with taxpayer money. Instead of delivering good governance, some of its leaders make news for eating expensive sushi off naked hostesses. Instead of providing school textbooks, they provide scandal. Instead of addressing criticism, they legislate against the press. And worst of all, the absolute worst thing, is that they continue to blame their own failures on the legacy of apartheid. They won’t accept any other argument, any other reason for South Africa’s slow progress—or, if we’re being honest, rapid regression. Instead of fighting against all racism, they nurture reverse racism.

When I was growing up, you did not want to be a black person in Krugersdorp police station. Nowadays, you don’t want to be a white person in any of the country’s police stations. In fact, you don’t want to be a person of any color who relies on the police for protection or the courts for justice. In South Africa, the police, like the ANC, are the problem, not the solution. And if a country’s health can be measured by the number of private security companies it has, South Africa is a very, very sick country indeed.

But I am still hopeful for its future. There are signs of hope; as there are examples of good governance, and good governors. But they are too few and far between. I keep searching for a Mandela among them. But there does not appear to be any leader in South Africa today to take up Mandela’s mantle. Perhaps Mandela’s passing will be another one of those moments where the entire country drops whatever it’s doing and looks in the same direction. The moment can be a reset; a reminder of the path still to be taken; an alarm bell for the ANC to stop blaming apartheid and get on with it.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Amir Mizroch is the managing editor of the English edition of Israel HaYom and the news anchor for TLV1 radio’s So Much to Say. His Twitter feed is @Amirmizroch.

Amir Mizroch is the managing editor of the English edition of Israel HaYom and the news anchor for TLV1 radio’s So Much to Say. His Twitter feed is @Amirmizroch.