Congressional Candidate Sean S. Eldridge Wants You To Know the ‘S’ Stands for ‘Simcha’

The husband of ‘New Republic’ owner Chris Hughes is putting a decade-old plan to run for office into action

Wealthy progressives have been hanging their hats in New York’s Hudson Valley for almost as long as they’ve existed in this country, starting with Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, who both grew up in Dutchess County and routinely repaired to the family estate in Hyde Park. In 1960, Gore Vidal made a run at a House seat that included the county seat of Poughkeepsie as well as a handful of surrounding towns, a campaign that touched off accusations of carpetbagging.

Now another idealistic, wealthy young liberal is vying to represent what today is the state’s 19th congressional district, a horseshoe-shaped entity that runs on both sides of the river all the way up toward Albany and Schenectady. Like Roosevelt and Vidal, Sean Eldridge has the luxury of being independently wealthy: His husband, Chris Hughes, the owner of The New Republic, was a Harvard roommate of Mark Zuckerberg’s and helped launch Facebook, affording them the ability to buy an estate worth nearly $2 million in the district to facilitate the run—after very publicly buying a $5 million spread an hour or so south in Garrison, in 2012.

But unlike his progressive predecessors, Eldridge has a Hebrew middle name—Simcha—and a family story that stretches from central Europe to Montreal, where he was born, and then to Ohio, where he was raised. His Jewish background isn’t something he hides, but neither is it something the candidate emphasizes; on the ballot, he uses a middle initial. “The name Sean Eldridge somehow doesn’t jump out at people,” he acknowledged, when we met for lunch in Rhinebeck in early May.

It only adds to the air of opacity surrounding the 27-year-old, who also runs a venture capital firm, Hudson River Ventures, based in Kingston, right in the middle of the district, and at least until recently was a regular sight in New York City and Washington, where The New Republic is based. The Republican incumbent, Chris Gibson—a local who served multiple combat tours in the U.S. Army and taught politics at West Point—has worked to make Eldridge’s recent arrival into both the district and public life the main issue in the race. “This is about him and his political aspirations, and I think that’s going to be a problem for him. He married well, he married into money,” Gibson told Politico recently. “But there are some things money can’t buy.”

Yet Eldridge clearly thinks of himself as a disruptor, like his husband and Zuckerberg. He points to his involvement in the marriage-equality campaign in New York and an array of other progressive issues as evidence that his priorities are better in touch with those of the district’s voters. Whereas he was previously content to work on politics “from the outside,” serving on the boards of local groups like Planned Parenthood and Scenic Hudson—and has been involved in the progressive power donor club Democracy Alliance—Eldridge has clearly decided that role isn’t for him. “The most important thing I could do is step up and run, and hopefully move our country in a better direction,” he says. “There’s such a lack of urgency. I think we need more urgency, more impatience.”

***

As recently as December 2012, Hughes was insisting to reporters that his husband had no immediate plans to get into public life. “No, no, no,” Hughes told his New York profiler Carl Swanson. “He’s 26. He’s going to do all kinds of things in politics, but I don’t think there’s any rush.” In truth, Eldridge has been openly planning his political career since he was a teenager. The winter 2005 newsletter of his alma mater, Deep Springs College, a kind of ranch-commune for hyper-intellectual young men in rural California, just north of Death Valley, includes the following entry: “Sean Eldridge comes from Toledo, Ohio, where he studied flute and starred in numerous high-school musicals. Sean is a citizen of Israel and Canada and will soon become an American to pursue a political career in this country.”

His mother, Sarah Taub, a family physician, was born in Petah Tikva, Israel. Her father, Zwi, is a former Hungarian soldier who survived the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp and met Eldridge’s grandmother, Gitta, a survivor of Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, at a refugee camp in Italy after the war. The family made its way to Canada, settling in Montreal, where Zwi worked as a tailor and Gitta as a hairdresser, raising their daughter in the Orthodox tradition. “My mother learned how to speak English by watching cartoons on television,” Eldridge wrote in a Mother’s Day post on his campaign website.

Taub insisted Sean’s father, Stephen, convert before they got married in Montreal. Eldridge was born there and spent his childhood going to a Conservative shul in Toledo—where his mother, now divorced, still lives, with her practice in nearby rural Milan, Michigan—after a brief stint in Ann Arbor. He went for one summer to Jewish summer camp outside Cleveland but spent a few more years at Michigan’s Interlochen arts camp.

It was at a Passover Seder in Montreal that Hughes first met the Eldridge clan. The young couple had been introduced by a mutual friend at a brunch in Cambridge in 2005, when Eldridge was working as a customer service rep at a moving company and Hughes was finishing at Harvard. Hughes went on to run the online organizing operation for Barack Obama’s first presidential campaign, while Eldridge finished his undergraduate degree, in philosophy, at Brown. He then enrolled at Columbia Law, but dropped out to join Evan Wolfson’s marriage-equality group, Freedom to Marry, after the New York State Senate voted against legalizing same-sex marriage in December 2009. By the fall of 2010, he had become the group’s political director, and the next year he made the New York Observer’s list of “power gays.”

Of course, the relationship with Hughes helped grease the wheels along the way. “There is nobody in the movement that is not going to take a call from Sean Eldridge, donor, advocate, what have you,” said one strategist at a leading New York LGBT organization, who insisted on anonymity for fear of compromising his relationships with donors. As a congressional candidate, Eldridge has benefited from the same dynamic, attracting the vocal support of everyone from Gov. Andrew Cuomo to Albany Mayor Kathy Sheehan to billionaire environmentalist Tom Steyer, scaring off potential Democratic primary challengers in the process.

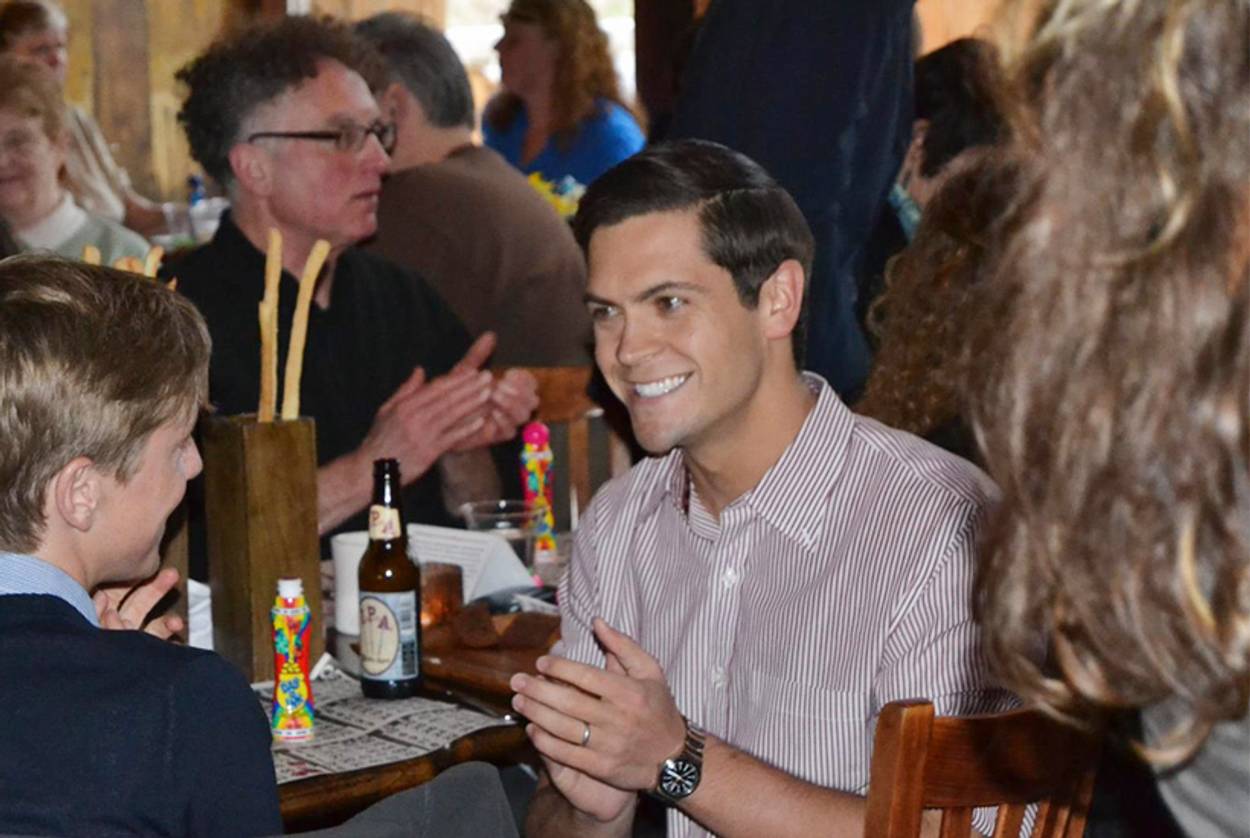

Except the thing that makes Eldridge a viable candidate isn’t his friends, per se; rather, it’s Hughes’ money looming over Gibson’s head like an anvil. It is somewhat ironic, then, that Eldridge is a fierce advocate for campaign finance reform, though he rejects the idea that being wealthy and channeling his personal fortune toward a campaign is inconsistent with wanting corporate cash to be less central to our democratic process. “When you’re in a position where you see how the system actually works and you see the amount of money in our political system, then you get a first-hand perspective of how broken it all is,” he told me when we met for lunch at Bread Alone, one of Hudson River Ventures’ pet projects, on a warm Saturday afternoon. “I’m blessed to be able to run and be independent and invest in my own race.”

He used the word “blessed” quite often in the few hours we spent together. But the logical jujitsu of simultaneously decrying money’s influence and trading in it seemed to elude him once or twice the course of our conversation, even if he fairly draws a distinction between self-interested corporate actors like the Koch brothers and independently wealthy philanthropists like himself and his husband, whose net worth is estimated at roughly $700 million. “As a candidate, it’s the Wild West,” he told me.

It’s a distinction many on the left are keen to draw, especially as progressive groups move to take advantage of the Supreme Court’s Citizens United ruling, which lifted restrictions on spending on elections by corporations, unions, and other groups. “Sean will be unbought,” said Josh Orton, political director at former U.S. Sen. Russ Feingold’s campaign finance reform group Progressives United and a guest, along with plenty of other movers and shakers in the progressive movement, at Eldridge and Hughes’ wedding reception.“I would never have any concern that he would be controlled or bought by industry.”

Indeed, just a few days after we met, the Chamber of Commerce announced it was dumping $300,000 into local TV spots to boost Gibson—a nice chunk of change, but still less than a third of the $965,000 Eldridge has poured into his own campaign from the family kitty. “I’m proud to not take any corporate PAC support or business association support to distinguish myself a bit and I hope to have a bit more of that independence,” he told me. Yet Eldridge was practiced enough to make sure to add that he isn’t too anti-corporation. “I think the conversation can get too shrill on both sides,” he said. “Corporations are not evil. Corporations create jobs, they create good products, and they’re all different, right?” He said he’s skeptical of wealth taxes of the kind advocated by the French economist Thomas Piketty—“My husband was educating me on this!”—because it would hurt local farmers whose property is assessed at a high rate even as they struggle to pay the bills.

“They literally sit around and read a lot, not just a little bit,” said another prominent LGBT political strategist who has been active in the movement for decades and knows the couple well. “Sean is actually going to get into the substance of stuff. He is not a surface-level person.”

There’s a palpable restlessness to him, a sense of how the world ought to be mixed with irritation that it isn’t so already. He is decidedly queasy about embracing the language of all-out confrontation with American elites; Eldridge is not an Elizabeth Warren-style candidate looking to connect with regular folks by invoking the 1 percent, which makes perfect sense given that the 1 percent are now his people. But he more than once brought up Warren and her brainchild, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, mostly in order to rip his opponent Gibson for voting against funding it. “I would love to hear how that helps our district,” he said, a little snidely. Clearly, though, his preferred mode is pragmatism: “You don’t want to go there and just, you know, say controversial things that draw attention to something if you’re not getting anything done.”

***

At a meet-and-greet at a supporter’s lush modernist home after lunch, Eldridge faced a couple dozen admirers sipping cocktails from plastic cups. He was on his own; Hughes was in Washington for the annual White House Correspondents’ Association dinner, partying at the Buzzfeed suite, while Eldridge stayed home to campaign.

Half the questions from the small crowd were about how to respond to the carpetbagger issue when it inevitably surfaces. The candidate’s answer then was virtually identical to the one he had given me an hour earlier over sandwiches: “Chris and I decided to move and live here because it’s an incredible place,” he said. “Many people have chosen this region.”

After his short remarks, which centered on a stump speech of elegantly delivered boilerplate progressive fare punctuated by a harsh dig at Gibson for supporting fracking, Eldridge slowly made his way from one elderly admirer to another for some glad-handing. His facial expression alternated frequently between a polite smile and intense stare, no surprise given that steely ambition is the single quality most often impressed on those who meet him. “Maybe he can be the Bloomberg of the Hudson Valley,” Melinda Fishman Jones, a content strategist who lives primarily in New York City, told me as people started to filter outside. “I think that would bring back an era, in modern times, of vitality and entrepreneurism.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Matt Taylor is an associate editor at VICE Magazine and former staff reporter at The East Hampton Star. His political reporting has also appeared in Slate, Salon, The New Republic, The Atlantic, The American Prospect, Capital New York, and New York Magazine’s Daily Intelligencer. His Twitter feed is @matthewt_ny

Matt Taylor is an associate editor at VICE Magazine and former staff reporter at The East Hampton Star. His political reporting has also appeared in Slate, Salon, The New Republic, The Atlantic, The American Prospect, Capital New York, and New York Magazine’s Daily Intelligencer. His Twitter feed is @matthewt_ny