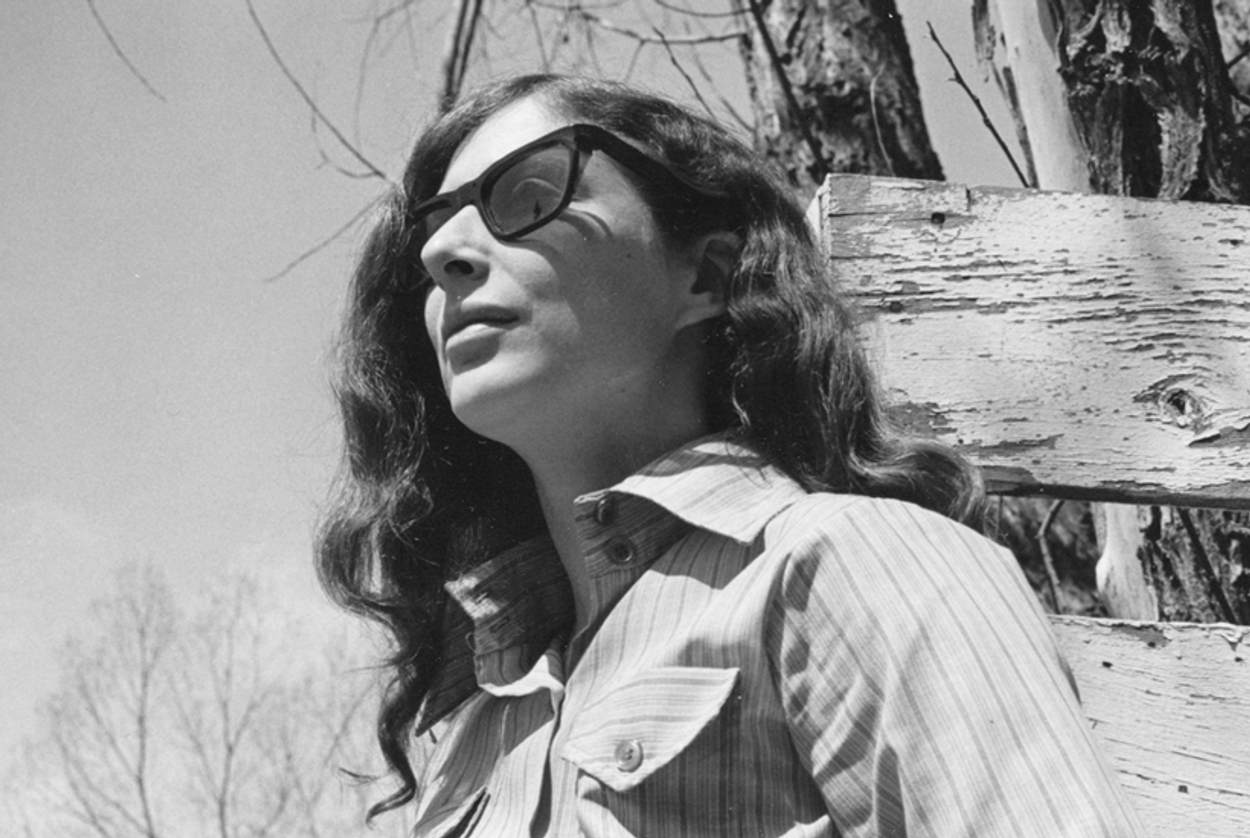

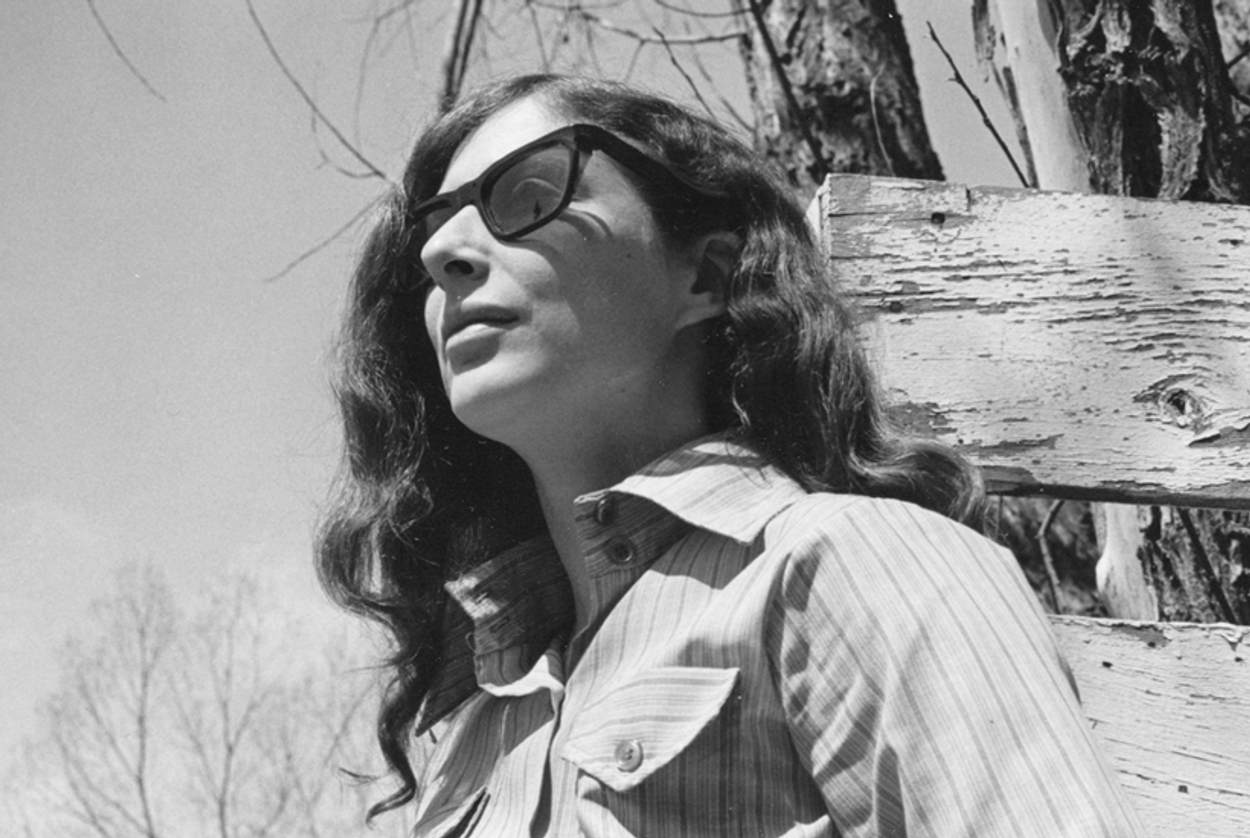

Ellen Willis’ Radical Jewish Sex-Positive Rock ’n’ Roll Politics of the Future

A new collection of essays by the late, great cultural critic affirms her standing as an icon of liberation and pleasure

In the introduction to The Essential Ellen Willis, a new collection containing 50 essays by the beloved critic, her daughter, Nona Willis Aronowitz describes the focus of her mother’s work as a “personal Venn diagram [of] rock music, woman’s lib, and grand, deliberately non-Washington politics.”

The book opens with an autobiographical essay describing Willis’ coming-out as a radical feminist writer and moves deftly through her archive, touching on everything from her nuanced appraisal of rocker Patti Smith whose androgynous image, she feels, plays into punk rock’s misogyny (“Beginning To See the Light”) to the war on drugs (“The Drug War: From Vision to Vice”), which she sees as a symptom of the confusion that has pushed American politics to the right and inspired large numbers of people to vote against their economic and social interests. The book brings together Willis’ essays on liberation and pleasure, Judaism, and gender, class, culture, and politics in a single sprawling volume organized chronologically by decade (1960s to the aughts).

Quite appropriately, it’s a wild ride. But what made Willis—who died in 2006 at the age of 64—truly unique was her dedication to steering clear of easy or prescriptive solutions and often ending her essays with questions rather than answers.

***

Willis came of age in the 1960s. Unlike many of her peers, she never traded in the cultural radicalism of her youth for the neo-liberalism that gave the Clinton family a political franchise and President Barack Obama a reputation as a lefty even while he bailed out investment banks rather than homeowners. And this book is, above all else, a compelling argument for a new political movement, a movement for liberation that takes cultural demands as seriously as economic ones and “recognizes equality and freedom, class and culture as ineluctably linked.”

Reading it in no particular order, as I did, underlined the consistency of Willis’ urge to see humanity reckon with its messiest, wildest parts and do it kindly—and in public. She wanted us to stop hiding behind prudish standards and voice our true desires, sexual, social, occupational, or otherwise. In her mind, the pursuit of pleasure is not a distraction from political movement but a powerful motivator for it. Willis blamed the ascendance of the Christian Right on the left’s failure to accept, embrace, and welcome our desires as legitimate: “What if the left had consistently argued that the point of life is to live and enjoy it fully; that genuine virtue is the overflow of happiness, not the bitter fruit of self denial; that sexual freedom and pleasure are basic human rights?”

It’s a fascinating idea to consider. What if our politicians asked us to show our patriotism through dancing joyously, not shopping the sale racks? How about if public debates over discriminatory sodomy laws argued that anal sex should be legal not only because the opposite is homophobic but also because anal sex feels good? If we didn’t see self-denial as a moral imperative would we have more love for fellow people, more empathy? Would we be less anxious about our own spending habits? Happier?

“Perhaps the definition of an authoritarian society is one in which people won’t stand up for or stand behind what they do, and prefer to think about the contradictions as little as possible,” Willis wrote in the 1986 essay “The Drug War: From Vision to Vice,” originally published in the Village Voice. For Willis, America’s failure to reconcile human desires with our tacitly agreed-upon narrative of national character is to blame for the “cultural schizophrenia” that haunts this country. And that schizophrenia, she argues, has vast consequences from criminalizing a person’s choice to smoke pot even though millions of people enjoy doing so, to preventing a woman from having an abortion despite overwhelming evidence that the procedure is common among all sectors of the American public.

As revolutions swept Eastern Europe in 1989, Willis wrote, “Tyranny is joyless. Freedom is pleasurable. Liberation from tyranny is ecstatic.” They are optimistic words, and at first read one may think the author was attempting to pass on a bit of American wisdom to the Czech and German protesters in the streets. But continue on into Willis’ essay “To Emma With Love,” and it is clear that her message was far from easy self-congratulation. “Revolution is contagious,” she writes. “Why not me? Why not us?” The implicit takeaway is that we Americans are not as free as we think we are; that our own liberation has not yet been realized.

Willis’ call for sexual freedom without punishment is all too relevant to the digital age. Think back to last month when a 19-year-old woman committed suicide after her former classmates found out that she starred in an amateur porn film and began harassing her online, calling her a slut, a prostitute, and related other things I am not going to pain myself to type.

Willis was a restless thinker with an uncanny ability to make decades-old ideas feel new. Her questions about the left’s tendency to follow the right’s lead on the tired tropes of bootstraps and sacrifice read like they could have been asked yesterday. No doubt we’ve made important progress in the realm of marriage equality and sexual freedom, yet the point is no less relevant. The gay marriage question has only moved toward resolution as it becomes increasingly framed as a question of family values; don’t gay people have the right to live in nuclear families like the rest of us? As for our right to pleasure, surely Willis would be horrified by the fact that progressives cloak in the armor of cost-benefit analyses arguments for things like the rights of inmates to have conjugal visits. (The argument goes that conjugal visits save the state money in medical care by reducing the chances that the inmate will harm himself or another inmate.) I would love to read her take on Michael Bloomberg’s attempt to ban people from using food stamps to buy sugary drinks, or on charter-school regulations that require children to walk in straight lines because their homes lives are chaotic, as is the policy at many urban charter schools.

One Willis essay I personally return to again and again is the 1977 essay, “Next Year in Jerusalem,” originally published in Rolling Stone. One of the longest pieces in the new collection, it tells the story of her secular brother Mike’s conversion to Orthodox Judaism and her trip to Israel to witness his faith and test her own lack thereof. “For the first time I faced a choice that was truly absolute, that included no tacit right to be wrong—the spiritual equivalent of a life-or-death decision in war,” she wrote. She flies to Israel to study Judaism in yeshiva like Mike, to discover if her brother—“what I might have become had I been a man”—was right about God.

Imbuing the quest with a panicky urgency is her question of whether this alleged God could be punishing her for refusing her “ordained role as wife and mother” by saddling her with a “prickliness” with men that undermines her ability to achieve happiness. “It was the message one would expect from a cranky, conservative-Freudian God, out to show me that feminism was the problem rather than the solution, that all this emancipation claptrap violated my true nature and would deny me the feminine fulfillment I really craved.”

It’s a humiliating fear for a feminist atheist to harbor. Yet Willis can’t fully discard the thought until she fully engages with it, talking with rabbis, living within her brother’s Orthodox community, and on the long walks alone, thinking about God. Considering the energy she puts into urging others to confront desire, it’s interesting to consider how she reconciles her own conflicting desires—the urge to find a male partner and the desire to continue life as an autonomous feminist; her desire to resist Judaism’s conservative social order and the wanting to be part of her ancestral community; the pull of atheism and the push of the God of the Torah.

Again, she confronts the contradictions and charts her own course within.

“For Jews like me, it was different,” she wrote. Instead of the 613 mitzvot, “we pursued utopian politics, utopian sex, utopian innocence.”

Indeed, in the end, Willis discovered that her brother’s faith and her own were not the same. Nor was their process of self-actualization. She returns to New York and its glittering skyline, which suddenly feels holy to her. The essay ends with a Bob Dylan lyric:

How does it feel

To be on your own

With no direction home,

Like a complete unknown?

But revolution is contagious and, thanks to this new collection, Ellen Willis will—and should—continue to be read.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Ariella Cohen is a writer and the executive editor of Next City, an online magazine about cities and urban policy.

Ariella Cohen is a writer and the executive editor of Next City, an online magazine about cities and urban policy.