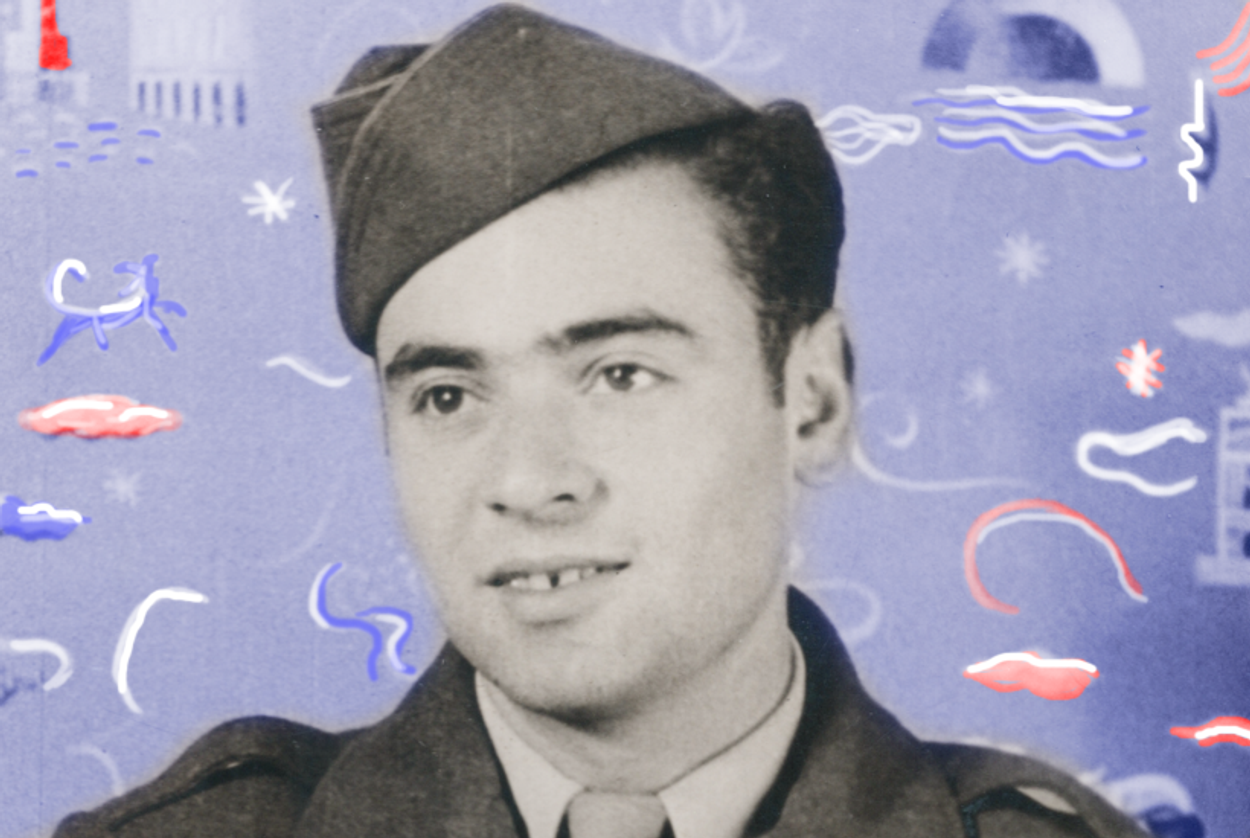

My Cousin Harry: A Jewish Story of the Greatest Generation

Through a portrait of a war vet who loved children, a glimpse of a lost Jewish-American world

My cousin Harry Krug, who died early last year at 88, was related to me only by marriage, but he couldn’t have been more braided into my mother’s extended family. This matriarchy was dominated by strong-minded women like Harry’s mother-in-law, my aunt Lily, stubborn and spiky as a Russian peasant, and Harry’s wife Pauline, a force of nature, who had crisp reactions to everyone she knew. The climate of our clan was heated, the atmosphere operatic; the men who married in had to surrender their passports and go native, as my mild-mannered father readily did, trading in his dour Polish kin for some Russian joie de vivre. Harry too jumped in with both feet. Through stormy scenes he remained as genial and unflappable as his wife was volatile. With his generous girth and dark good looks, his twinkly, mischievous smile, he seemed impossible to upset. Whatever the weather, no one was going to spoil his day.

Pauline and Harry, both born in 1924, met when they were 12 and became high-school sweethearts on the Lower East Side. They always planned to marry, but the war intervened and he was tapped for what would one day be dubbed the Greatest Generation. A year or so before he died I called him as part of my research for a memoir—he was one of the few people still around who had vivid memories of my childhood. Instead we spoke for an hour about his army experiences, none of which I had heard before, since he rarely talked about himself. Conversations with Harry usually focused on your life, about which he was endlessly curious, joshing, and funny. Unlike New York’s late, voluble mayor, he always wanted to know how you were doing.

When he was drafted at 18, he told me, he was a complete innocent, totally unworldly. He had never been out of New York, had barely left the Lower East Side, never smoked or drank (not even coffee, he recalled with amazement), and never knowingly strayed from kosher food. In the army at first he abstained from eating meat, only to find he couldn’t keep going on such a meager diet. Then, on his father’s advice, he tried simply to avoid pork. But after consuming what seemed like a veal chop, he found instead that he’d eaten a pork chop. This became part of his ongoing education.

At boot camp in Louisiana, Camp Claiborne, he was thrown together with even more clueless men from the South and Midwest who habitually razzed him as a Jewboy, a kike. They were shipped overseas on the Queen Mary, 4,000 men in a single rocky, rainy sailing, then stationed in London preparing for the invasion of France. I had seen Saving Private Ryan but Harry’s description of the D-Day landing went beyond those gory images, with men falling all around him and corpses littering the beach. They remained pinned down on the beach for a full week. To me such a life-and-death situation was difficult to imagine, as hellish as being thrown into a concentration camp. Eventually he was sent to the deep-water port of Cherbourg, which had been liberated three weeks after D-Day. “The men around me had more brawn than brains,” he told me. “Even the officers made fun of Jews, but they found I was good with numbers and set me to work.” He survived the next months to fight in the Battle of the Bulge, a near disaster for the Allies, then learned that back home his mother had died. She was never told he had been sent overseas.

Emerging from the war penniless and ambitious, Harry followed a path for his generation: He married the girl he left behind, and they began having children almost immediately. He moved from company to company, from sales to management; they relocated from one gilded suburb to another. Eventually he became a well-paid executive, the father of four growing children on whom he doted extravagantly. Their married life had begun in a walk-up apartment on Roosevelt Avenue in Jackson Heights, where the elevated train roared in their ears, but they moved on to towns on Long Island, then to St. Louis, Cleveland, and finally to New Jersey. Family and child-rearing were the one constant, for no one loved children more than Harry, and no one I knew was so good with them—easy, natural, and ingratiating. I felt this as a child, 16 years his junior, and I saw it again in the ways he effortlessly engaged with my own kids and his grandchildren, who all got to spend time with him. “He had a large personality, he was funny, and he really seemed to like talking to you,” my daughter told me the other day. “He remembered everything you’d said, so you felt acknowledged by him. Most people don’t really like to talk to kids. You could tell he did.”

Never at a loss for words, he took kids seriously, quizzed them about their lives. There was something irrepressibly childlike about him, a sense of wonder he never gave up. Any project, any excursion was worthwhile if children came along. He teased them, tickled them with his banter, took them fishing; he was someone really interested in what they had to say. But he was just as gregarious with strangers, flirting harmlessly with waitresses, tipping generously, showering them with compliments and mock complaints until he set them giggling.

It was during the early summers of his marriage (and my childhood) that I got to know him best. We all called him Poogie, his wife’s nickname for him; “Harry” was reserved for formal occasions. Wherever he and his family were living then, once school let out they would return each year to Rocky Point, then a small blue-collar town on the Long Island Sound. There my mother and three of her brothers and sisters had built or bought rude cottages—bungalows, we always called them. There I grew up in a boisterous crowd of aunts, uncles, and cousins, some with histrionic personalities reminiscent of the Yiddish theater. For the sake of their children, but also out of attachment to the family, especially her feisty, widowed mother, Pauline and Harry would move their kids from a comfortable suburban ranch house to the equivalent of a railroad flat filled with beds, lacking every amenity imaginable. Well into the 1950s the house, built room by room with help from relatives and friends, had neither running water (instead, a hand-pump in the back yard) nor an indoor toilet (only a one-seater outhouse far back on the small lot). The bungalow also came equipped with a difficult mother-in-law. Yet he loved to return to this poor-people’s paradise, where he taught himself carpentry and put his working life out of mind, since this was where he and the kids felt most at home.

During the day this tribe of cousins frolicked in sun, sea, and sand on pebbly beaches that dotted the pristine surf of the Sound. Then, as twilight descended, with no television for distraction, the men played cards on screened-in porches while the women gathered on the lawn for a never-ending stream of gossip, seasoned with ancient family feuds. So, I grew up amid a gaggle of surrogate parents, Pauline and Poogie my favorites among them, for they were younger, bolder, less anxiety-ridden than my own folks. “I’m cold, go put on a sweater,” my mother would say to us, no matter how warm the evening. This amused Pauline so much she loved repeating it.

These summers ended when I turned 15 and went off to jobs in Catskills hotels and in summer camps in the Poconos. I saw Harry, Pauline, and their kids less frequently, but the early bond never weakened. They were among the few who welcomed my blunt, plain-speaking wife—born of German-Jewish, not East European extraction—into the family, and she took to them as much as I did. Harry appreciated forceful women, appreciated women in general, while Pauline took pleasure in a kindred spirit, prone to speak her mind, who was treated like an outsider by my mother and her two sisters. Pauline was a fountain of vitality, a seemingly unstoppable force, but to everyone’s dismay she fell ill and died of breast cancer, the family curse, in the mid-1990s. At her funeral Harry seemed, for the only time in his life, completely blighted. He eventually married again, luckily to a woman as warm and sociable as he was. Still full of family feeling, he became almost as involved with her children and grandchildren as with his own. “We thought we might have five good years together,” Shirley told me later. “We had 13.” He was grateful for the second chance.

Through all these changes we never lost contact. I would always be something of a kid to him, and as I grew older, after my parents died, my friendship with this last surviving throwback to my youth gave me a rare pleasure. Our phone conversations would always begin in the same way, “Hi, this is your favorite cousin,” to which the response would be, “Well, this is your favorite cousin.” He kept track of everyone’s birthday, and I mean everyone, children, grandchildren, cousins, spouses, no doubt many friends as well. He called partly with good wishes but mostly just to keep up. In later years he tried email and Facebook, convenient for posting pictures, but the telephone was his medium as he grew older. He typically wanted to know if I had published anything and would scold me if I hadn’t sent it to him, not necessarily to read but at least to put it on display, if only as a conversation piece, some grist for the daily mill.

Now that he is gone I’ve lost not only a warm friend but one of the few remaining links with my own past. A chunk of generational history was writ large in his journey, a circuit from the depths of Depression and bloody warfare to unexpected peacetime prosperity, from a miserably poor immigrant ghetto to handsome suburban comfort and, finally, to busy retirement in a warmer climate, in his case a gated community in Florida. Not all the war veterans prospered in the world that followed, the thriving economy, a postwar golden age for the nuclear family, but Harry was fortunate as well as canny and cautious. Like most children of the Depression he was careful about money, even frugal, but open-handed with those close to him. When my son became a junior stock broker, directly out of college, Harry was one of his first clients, not venturing much money but eager to show him the ropes, not afraid to be demanding, unpredictable, as if tutoring him with tough love while keeping an eye cocked for his own investment opportunities. An optimist to the last, he felt there was always something that might turn up, a stock tip, a mutual fund, and it made him quite happy to keep it all in the family.

Morris Dickstein, distinguished professor emeritus of English and theater at the Graduate Center of the City University in New York, is the author, most recently, of Dancing in the Dark: A Cultural History of the Great Depression. His memoir, Why Not Say What Happened: A Sentimental Education, will be published by Liveright in February.