The other thing that Lyndon B. Johnson did exactly 50 years ago, in late April 1965, apart from preparing the historic and revolutionary Voting Rights Act, was invade the Dominican Republic. The invasion was a Cold War episode. In Cuba a few years earlier, the old Batista dictatorship had collapsed, and power had fallen into the hands of Fidel Castro and the Cuban Communist Party, which represented a triumph for the Soviet Union. And, in Washington, D.C., the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations worried that, under the wrong circumstances, similar developments might take place next door in the Dominican Republic. The old dictatorship there was Rafael Trujillo’s, which collapsed in 1961, when Trujillo was assassinated. A writer named Juan Bosch came to power. Bosch was a democratic socialist in the Latin American style, with big ideas about social reform, all of which seemed good, from the standpoint of the United States. John F. Kennedy received him in the White House.

Only, the Dominican army never could reconcile itself to the collapse of the old dictatorship. The Catholic Church was not too happy about the big reforms. And the army mounted a coup. Bosch’s supporters, the Constitutionalists, responded with an uprising. Fighting broke out in the streets of Santo Domingo. This was the “April War” or “April Revolution” of 1965. Gun battles on the Calle Conde. These seemed the wrong circumstances. And on April 28, President Johnson launched the invasion—which, in the United States, hardly anyone remembers, and which, in the Dominican Republic, everyone remembers.

***

What were the consequences of Johnson’s invasion, seen 50 years later? There were a million consequences, not only for the Dominicans. I point to a very tiny but splendidly illustrative one, which bears on the poetry scene in New York City—a strictly literary consequence. The English-speakers of New York sometimes forget that, in their town, literature has never been a mono-lingual affair. There was a period in the 1920s and ’30s when Yiddish was New York’s second literary language, or maybe Yiddish was the first language, judging from the grandeurs of The Penguin Book of Yiddish Verse. Arabic had its moment, back in the days when Khalil Gibran, the admirer of Whitman, presided over the Arab writers of the New York Pen League. I wonder what there has been in Dutch, German, Italian, Gaelic, Russian, Chinese, and everything else. But the longest-running of the New York literary languages, after English, has of course been Spanish, beginning in the 19th century with José Martí and advancing to the New York poems of Rubén Darío, and onward. And during this last 50 years the Spanish poetry of New York has inevitably taken a Dominican turn—nourished by the defeated Constitutionalists of 1965 in their New York exile, and then by the immigration to Upper Manhattan and other neighborhoods, and finally by a fecund intermingling of New York and Santo Domingo, in inter-latitudinal embrace.

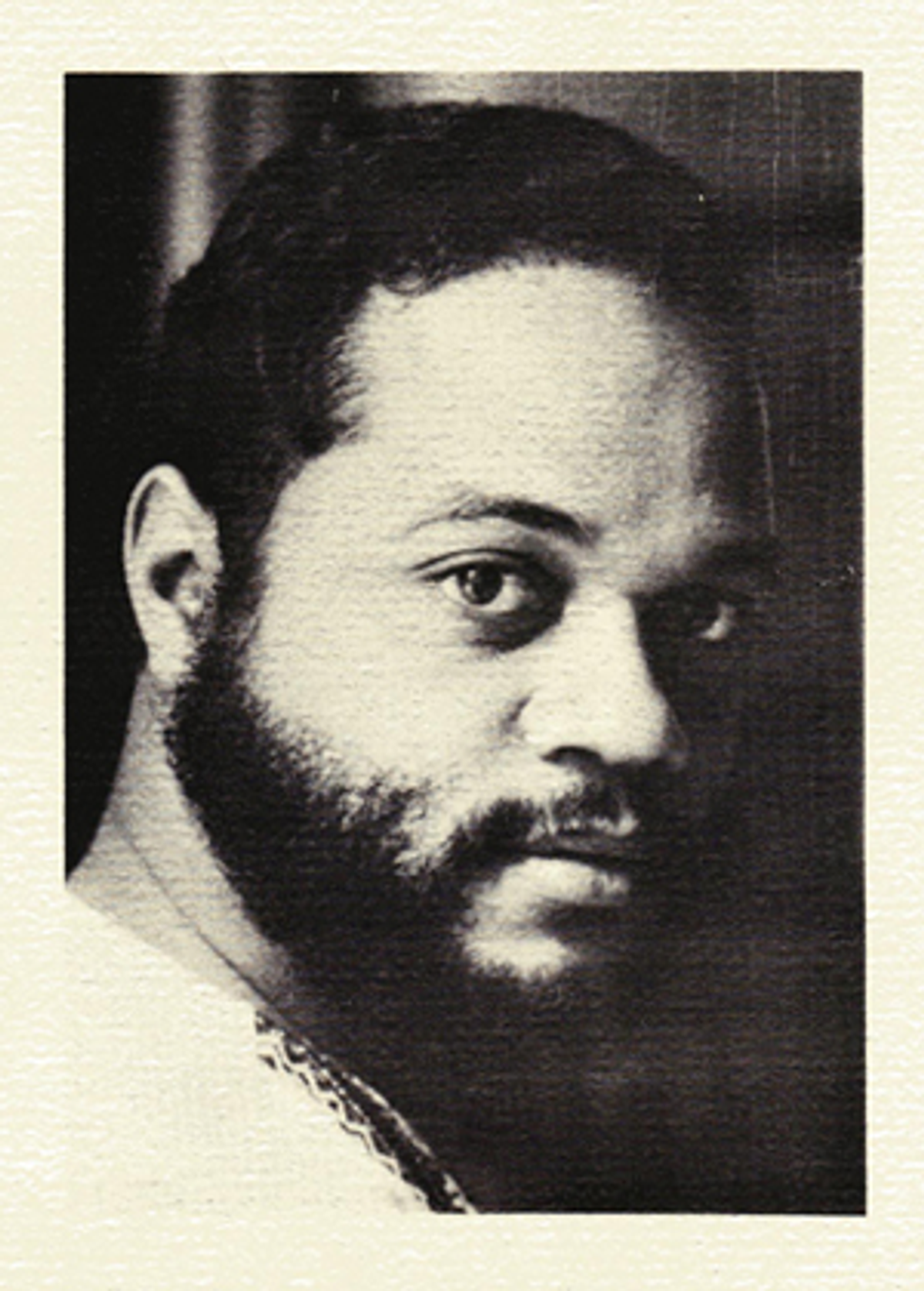

You can see a hint of these developments in Mario Vargas Llosa’s novel about the assassination of Trujillo, The Feast of the Goat, with its landscape that floats back and forth from one city to the other. You could point to the writings of the Dominican-American novelists. But I cite another example, not too well-known in the United States, which is another Feast, or El Festín: (s)obras completas, by the poet Alexis Gómez Rosa. This is a curious volume the size and shape of a shoebox, 1,500 pages long, published in Santo Domingo in 2011, containing hundreds of poems on all kinds of themes. Yet if any single one among those many poems can be regarded as central to the larger work, it would have to be a 30-page epic called “Truce of the Mammals,” from 1977, the longest of his poems. Here is the 1965 invasion and the April War, seen from a standpoint of someone who in those days was 14 years old and maybe not too political at the time but who, even so, feels the experience keenly.

The poem is halfway a surrealist delirium in a style that reminds me of Octavio Paz. And it is halfway a “testimonial” or documentary poem in the left-wing Latin American style of the 1970s—with the two styles rendered into one by a terse rhythm. And at the center of this central poem stands a shocking image, which is the incongruity of the invasion. The Nicaraguan poet Pablo Antonio Cuadra composed a famous poem about the U.S. Marines intervention in Nicaragua in the 1920s, called “Poem of the Foreigners’ Moment in Our Jungle,” which contains these lines:

In the heart of the jungle,

500 North Americans!

in which the exclamation mark says it all. And Gómez Rosa’s poem expresses the identical shock, except on a bigger scale, and with disdain instead of an exclamation:

42,000 Marines climb down from gray aircraft carriers

and helicopters.

The pineapple is sour, sir.

And Gómez Rosa goes on to invoke bitterly the names of Dominicans who fought in the war, and some of those who died. A footnote attached to the poem in The Feast explains that, on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the invasion, in 2005, the Dominican government brought out a special edition of the poem, and this makes sense, given that, by then, the heirs of the old Constitutionalist movement had come to power (and remain in power today and seem to be doing fairly well). But I do not mean to suggest that Gómez Rosa is a political militant.

Mostly he attends to rhythms and cadences. A poem called “Nature of the Surprised Eye” in its entirety (if the poet and my readers will forgive my translation, here and elsewhere):

— The River —

White its curls

in the water braided, white its long

fingers, without ending

in fingernails.

Leaping over the rocks, white

its fabulous fish.

which I like because, bobbing beneath the short lines, the word “white” surges ever forward, as in the motion of a ripple or a wave.

He composes haikus:

To dream is easy.

The flesh all solitary,

and ravens, the mind.

And he seems pretty much obsessed with Octavio Paz—as if, for Gómez Rosa, to dream is, in fact, easy. Crazy images chase each other across the page. Still, he is not exactly Pazian. The whole point of Paz’s surrealist experiments is to make you think about the larger program that lies beyond the poems—the wild idea that dream-truths, if properly evoked in art, will open a window on the coming social revolution: the idea that poetry contains the secret of human progress. You do not have to believe this idea to read Paz: You merely have to see the excitement in it. But this idea is not Gómez Rosa’s, even if he indulges in surrealist non sequiturs. He does not appear to be in search of hidden depths. His poetry opens a window, instead, on other poetry, or on some text or another, or maybe on the encyclopedia. One of the larger poems in The Feast (though scarcely as large as the one about the American Marines in Santo Domingo) is called Octavio Paz. It begins:

Stretched out, your

nakedness

on the white

you are the black.

which is not much of a beginning, with the white and black referring to the white page and black type. A footnote is appended to the title, though, which refers us to a footnote in a different poem, which is called Carbon Copy and the Carbon Itself, which explains who was Octavio Paz , encyclopedia-style: “Mexican poet, essayist, translator and diplomat … ”. And then Carbon Copy and the Carbon Itself circles back to Paz still another time by means of a parenthetical scholarly citation, written as verse:

Your body is the shadow of my body.

(Better Octavio Paz, Pasaje, in La Centena, p. 194)

which, if you have the patience, should lead you to look up Pasaje, by Octavio Paz. Which I have done. Sure enough, Paz’s poem outdoes Gómez Rosa’s:

More than air

more than water

more than lips

light, light

Your body is the track of your body

But it is amusing to go chasing Gómez Rosa’s footnotes and citations from one poem to another. And there is a strong suggestion that, by means of his footnotes and scholarly citations, he is conjuring a program of his own, entirely different from the surrealist program. His program is to conjure into existence a vast textual universe—a universe of poems in constellation with other poems, and in constellation with the history of Dominican verse, and with still other parts of life.

He dotes on boxers:

Annotations on Fame

(Commentaries on Sugar Ray Leonard attributed to Angelo Dundee)

Pindarus in his Triumphal Odes

would have celebrated him.

Borges, the unpredictable ironist, certainly

admired him and guarded his opinion.

and so forth, to which he attaches seven footnotes, which fill the bottom half of the page with explanations of who was Angelo Dundee, Pindarus and everyone else.

And in this universe of Gómez Rosa’s, the textual universe of encyclopedic poetry and boxing and the 1965 invasion and everything else, New York appears and reappears—the New York where the poet has evidently spent some years—New York, his second city: the Dominican New York that has come into existence during this last half-century; the New York of Washington Heights and Harlem and St. Nicholas Avenue. Sometimes he strikes a grand tone in evoking this New York of his. A poem called Tiemann Place (which is a street one block long in Upper Manhattan, down the hill from Grant’s Tomb) begins:

Tall and erect, solitary and nervous,

Surged from the heart of Whitman,

borders (a cosmos) the street, which toward Tiemann

Place ends in an asphalt dome.

House of General Grant, house awaiting

its history, first circle of the trees:

early morning.

which, apart from invoking Whitman, invokes faintly the great Darío and his own salute to Whitman, from more than a century ago. Darío was a genius at presenting himself as a tragic figure—a man of heartbreak. Gómez Rosa is not so weepy. He does tell stories, though. The poem about Grant’s Tomb moves down the block to an apartment on Tiemann Place where, as the birds begin to chirp at dawn, the poet gets up to depart from a lover’s bed. “The whole of you was a pair of eyes … ” I love the poem. The romance of New York is in that poem—the New York of Whitman and Grant, a Civil War New York, as observed in a post-1965 Dominican Spanish whose memories pass through Darío.

Johnson’s invasion, then—what did it bring about? If you want to read about the immediate sufferings that resulted, you should read Gómez Rosa’s epic poem about the invasion. If you keep on reading, though, you will discover that, in the aftermath of the invasion, still larger events took place. Instead of 42,000 Marines, 600,000 immigrants. And subtler events. Apart from everything else, the poetry of New York took on new colors. Maybe Dominican poetry has likewise been enriched. A literary advance was not among President Johnson’s intentions. By mentioning it, I do not mean to sound a note in favor of the invasion and its tragedies. Still, the invasion created new circumstances, and people adapt, and life goes on, and feasts are spread, and sometimes life is good.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.