The candidate runs for president in a time when police violence against black people is screamingly visible, and black Americans are rising up (mostly nonviolently, sometimes violently) in righteous indignation. Vociferous protesters demand new laws to protect the rights of African Americans. The candidate responds: “No matter how we try, we cannot pass a law that will make you like me or me like you. The key to racial … tolerance lies not in laws alone but, ultimately, in the hearts of men.”

The candidate was Barry Goldwater in 1964. The civil rights movement was boiling, but Goldwater was opposed to a public accommodations law banning racial segregation, which would be, he said, “unconstitutional” and would “only hinder not help the cause of racial tolerance. Such a law could even open the door to a police-state system of enforcement.” He maintained that no new law was necessary, “the right to vote” and “to equal treatment before the law” having been “clearly guaranteed by the 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution. These rights should be rigorously enforced.” But, he added: “Unenforceable government edicts benefit no one.”

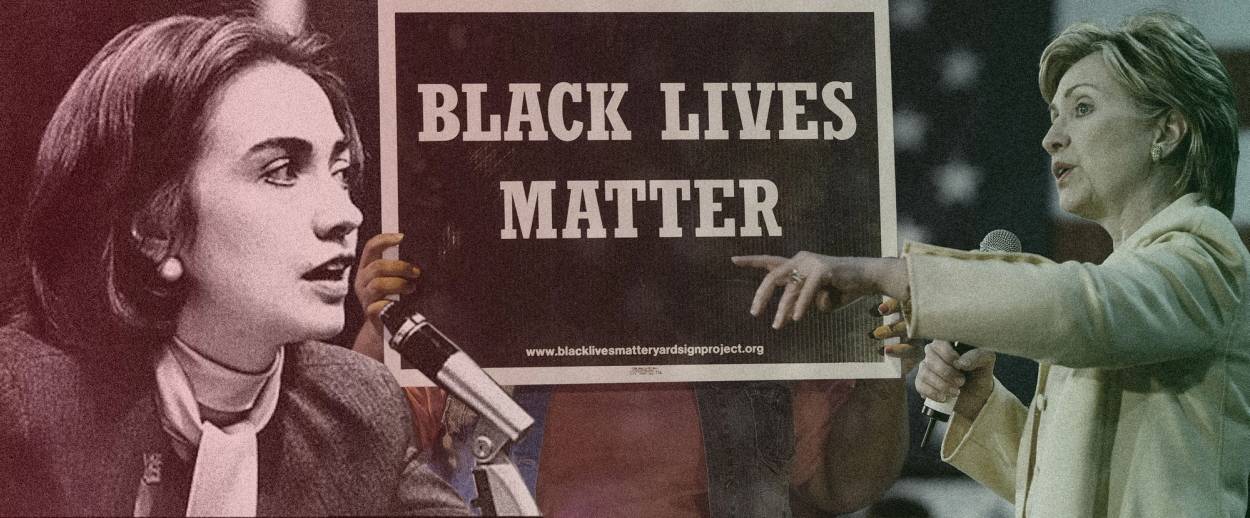

Interestingly, Barry Goldwater’s campaign was the maiden political venture of a young Illinois Republican who, by her own much later account, was “a Goldwater girl, right down to my cowgirl outfit and straw cowboy hat.” Now, 51 years later, she is the leading Democratic candidate for president. But in 2015, it is Hillary Clinton who emphasizes the importance of laws, and the leading public advocate of heart-changing is a young man named Julius Jones, a Black Lives Matter (BLM) activist from Worcester, Massachusetts, who, with others, confronted candidate Clinton at a private encounter she agreed to after a rally in Keene, New Hampshire. Thanks to ubiquitous video, the conversation later went public, and Salon published a transcript.

Jones accused Clinton of “saying what the Black Lives Matter movement needs to do to change white hearts.” In her rejoinder, Clinton said passionately:

Look, I don’t believe you change hearts. I believe you change laws, you change allocation of resources, you change the way systems operate. You’re not going to change every heart. You’re not.

Perhaps realizing that she had overpolarized the distinction between hearts and laws, Clinton went on:

But at the end of the day, we could do a whole lot to change some hearts and change some systems and create more opportunities for people who deserve to have them, to live up to their own God-given potential, to live safely without fear of violence in their own communities, to have a decent school, to have a decent house, to have a decent future.

And then she endorsed the movement while at the same time underscoring its limits:

So, we can do it one of many ways. You can keep the movement going, which you have started, and through it you may actually change some hearts. But if that’s all that happens, we’ll be back here in 10 years having the same conversation. We will not have all of the changes that you deserve to see happen in your lifetime because of your willingness to get out there and talk about this.

Clinton’s initial phrasing encouraged subsequent reports to oversimplify the argument as one between changing laws and changing hearts, with the BLM activists cast as the heart-changers. But in this polarization, the BLM activists collaborated; in no small part, they cast themselves that way. Clinton, by contrast, cast herself as the politician who learns from changing conditions and needs. Partisan of laws, she argued with the Barry Goldwater (and presumably herself) of 1964: Hearts are never enough. They may be necessary but they’re not sufficient.

Clinton acknowledged that her husband’s 1996 crime bill had produced some bad, though unintended, consequences—massive incarceration—but insisted, rightly, “that there was a different set of concerns back in the ’80s and the early ’90s.” Indeed, as Kevin Drum pointed out in Mother Jones,

in 1994, it was the [Congressional Black Caucus] that saved President Clinton’s crime bill after an unexpected loss on a procedural vote. So, was the 1994 crime bill racist in intent? No. Many black leaders, including black mayors who faced rising crime rates daily, supported it. Violent crime really was a huge problem—and it really was especially severe in black communities. Nobody at the time knew lead might be the culprit for this, so they had to address it as best they could given what they believed. So they did. The 1994 crime bill was not a white supremacist project. It was a crime bill.

Last week, without retracting her 1994 view, Clinton read out of the standard politician’s playbook: Look forward, not back. “And now I believe that we have to look at the world as it is today and try and figure out what will work now.” Or as Keynes put it more pithily, responding to a charge that he had changed his views on monetary policy over the years: “When my information changes, I alter my conclusions. What do you do, sir?”

Challenging Clinton’s law talk, Jones returned to heart talk:

You know, I genuinely want to know, you, Hillary Clinton, have been in no uncertain way, partially responsible for this. More than most. There may have been unintended consequences. But now that you understand the consequences, what in your heart has changed that’s going to change the direction of this country?

Jones wanted to know if Clinton could be trusted to act on her perception—an accurate one—that over the past two decades a crime bill that once had constructive aspects is now overwhelmed by its negative consequences. If he wanted her to subscribe to his view that the 1994 act was motivated by white violence, she could not be expected to go along. Indeed, it’s hard to make a case for his view. But she could say bluntly that what’s changed in her heart is that she sees the overwhelming social pain caused by massive over-incarceration, however arguably well-motivated at the time, and is deeply committed to intelligent remedies.

It’s important not to overpolarize this debate. To change laws, office-holders have to change hearts—their own hearts, the hearts of other office-holders, and often enough the hearts of their supporters as well. This is especially true when newly proposed laws run ahead of public opinion (which was certainly the case in 1964). To get their own hearts stirred, the office-holders often enough have to listen to the clamor of movements of outsiders. And, as Clinton recognized, hearts do not change unless minds also change. The polarities are artifacts of a stiff, starchy, weak understanding of the interconnections of hearts and minds.

The Hillary Clinton who understands this is the Hillary Clinton whose only authentic-sounding passages, in her book Living History, are the ones where she speaks as a devotedly church-going Methodist—a moralist with a mission. This is the Hillary Clinton who, as she sought to remind her interlocutors in Keene, is a longtime, fervent partisan of the Children’s Defense Fund. When she speaks and writes in that voice, she does not sound like a cut-and-paste machine.

But it’s striking also that Jones too spoke not only to hearts but also to minds. His reply to Clinton preached in behalf of an analysis. “America’s first drug is black slave labor … and until someone takes that message and speaks that truth to white people in this country so that we can actually take on anti-blackness as a founding problem in this country, I don’t believe that there is going to be a solution.”

Clinton the righteous Methodist spoke up in behalf of a wrenching national reeducation, though she said so almost in passing: “I think that there has to be a reckoning.” Then she segued, as she must, into the mind of the politician:

I also think there has to be some positive vision and plan that you can move people toward. Once you say, I mean, this country has still not recovered from its original sin—which is true—once you say that, then the next question, by people who are on the sidelines—which is the vast majority of Americans—the next question is, “Well, what do you want me to do about it? What am I supposed to do about it?” That’s what I’m trying to put together in a way that I can explain and I can sell it. Because in politics, if you can’t explain it and you can’t sell it, it stays on its shelf.

About this, she’s dead right.

“In your heart,” went a pro-Goldwater slogan of 1964, “you know he’s right.”(The unofficial Democratic rebuttal was: “In your guts, you know he’s nuts.”) But in 1964, Goldwater was not the lone Republican to care about hearts more than laws. George H. W. Bush, running for the Senate from Texas, did so as well. And it wasn’t only Republicans who were so heart-friendly. Establishment views of the time leaned heavily on hearts. But hearts, coupled with minds, were Democratic favorites as well. Twenty-eight times Lyndon Johnson famously used some version of that phrase—it was what he wanted to “win” in Vietnam. (The hawkish riposte, from some unknown wag, was: “When you’ve got them by the balls, their hearts and minds will follow.”)

Black Lives Matter is admirably riding, and stirring, a current that could move forward desperately needed reforms, top to bottom, in the criminal justice system. Clinton did rather well at accepting their contribution. But Clinton is not the only player groping toward some understanding of the symbiosis between insider and outsider politics. As Russell Berman pointed out in The Atlantic, a few days after the encounter in Keene, some activists, at least, were ready and waiting with precisely the kind of plan she was calling for. Their program, available at a website called Campaign Zero, represents, in their own words, a coalition of “activists, protesters, and researchers.” Black Lives Matter and its supporters need to wrangle about the particulars—as do Clinton and her advisers. They would be well-advised to consider seriously Campaign Zero’s agenda, which rejects “broken windows” policing, advocates limits to force, better training, more body cameras, demilitarization, and fair police contracts.

What Black Lives Matter well understands, as neither Barry Goldwater nor today’s gaggle of Republican candidates did, is that neither hearts nor minds nor laws change without protest in the streets. In 1964, Goldwater made another stern pronouncement: “Our people must not be herded into the streets for the redress of their grievances.” The later Goldwater, a born-again partisan of civil liberties, would have known better. He would have paid closer attention to the First Amendment, the part about “the right of the people peaceably to assemble, to petition the government for redress of grievances.”

Black Lives Matter’s assemblies are the fuel for long overdue reform. It will be interesting to see how the 17 current Republican presidential candidates respond. How do they feel about hearts, minds, and laws that pertain to equal treatment of American citizens?

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.