To be a Hilltop Youth is to first disaffiliate with all establishments in Israel. Especially the settlements. These young Hasidic-looking men and women make their homes out of trucks, cars, trailers, caves—anything suitable for a makeshift shelter—atop the hills of Judea and Samaria. They see themselves as connected to the Land of Israel, not to any of the institutions of the Israeli state. The very violent group among them consists of no more than a few dozen core members and a few hundred more who support them in public demonstrations and on social media. Some in Israel refer to them in disgust and horror as “Jewish ISIS,” and while there’s a great distance between Al Baghdadi’s practice of beheading, burning alive, and massacring thousands of people and the violence of extreme members of Hilltop Youth, there is indeed a deep connection between the two phenomena.

ISIS is not just a state—it’s an idea, and a powerful one: throwing away modern norms and acting to revive the golden age of the Islamic Caliphate. And just like the Caliphate, the methods to achieve it are pre-modern: “Din Muhammad Bissayf,” the religion of Muhammad is [enforced, spread] by the sword. The success of such cruel methods within the blurry borders of Iraq and Syria has drawn young enthusiastic Muslims from around the world to Syria. Similarly, ideas of reviving the thousands-of-years-old Kingdom of Judea draw young enthusiastic men and women to the hilltops, where the leaders and idea-men of the Hilltop Youth promise their followers a sense of authenticity in a post-modern world. As with ISIS, this authenticity is predicated on destroying all institutions of the State of Israel, which is undeserving of recognition.

Hilltop Youth abandon the communities in which they were raised to live in trucks in uninhabited regions of the Judean Hills. In their nativist ideology, they are the real Jews upholding the “true” Jewish way, and they encourage each other to strive with violence and terror against non-Jews in order to retaliate against Arab terrorism and to establish a pure Jewish existence on the land of Israel. The State of Israel is evil, and the religious communities and ideologies that support it are misguided, they believe. Their nativism perceives the State of Israel and its supporters as “Erev Rav,” a Kabbalistic term that refers to people who look like Jews but have the souls of enemy gentiles.

The first inclination of many observers is to label young people who seek out nativist causes like ISIS or the Hilltop Youth as “crazy,” “lunatics,” or “hormone-laden kids.” But behind this perceived lunacy is a certain philosophy, or a general tendency, that we can trace back to leaders who either taught fundamentalist and nativist philosophies or whose teachings have been interpreted to support violence and terror.

One such leader purports to affiliate with the Chabad movement in Israel. His name is Rabbi Yitzchak Ginsburgh, and many Hilltop Youth attended the yeshiva Od Yosef Chai where he serves as president in the settlement of Yitzhar, a community that is home to some of Israel’s most extremist settlers. Chabad scholars have long dismissed his teachings, considering them to be eccentric and at times even in direct contradiction to Chabad’s scholarly approach. In a famous lecture during his protest of Israel’s disengagement from Gaza and removal of the Gush Katif community on its banks, Rabbi Ginsburgh poetically interwove Chabad and Kabbalistic writings to promote the delegitimizing of the State institutions. Known as “The shell and the fruit,” Ginsburgh’s speech used mystical metaphors to encourage the destruction of “shells” around the Jewish people. The sages compared the people of Israel, said Rabbi Ginsburgh, to a nut, and the nut has three shells. The shells, according to him, are Zionism, the Israeli courts, and the government. Now, said Rabbi Ginsburgh, the time has come to break the shells, overthrow Zionism, disobey the courts, and oppose the government—every government—until a true Jewish regime is reborn.

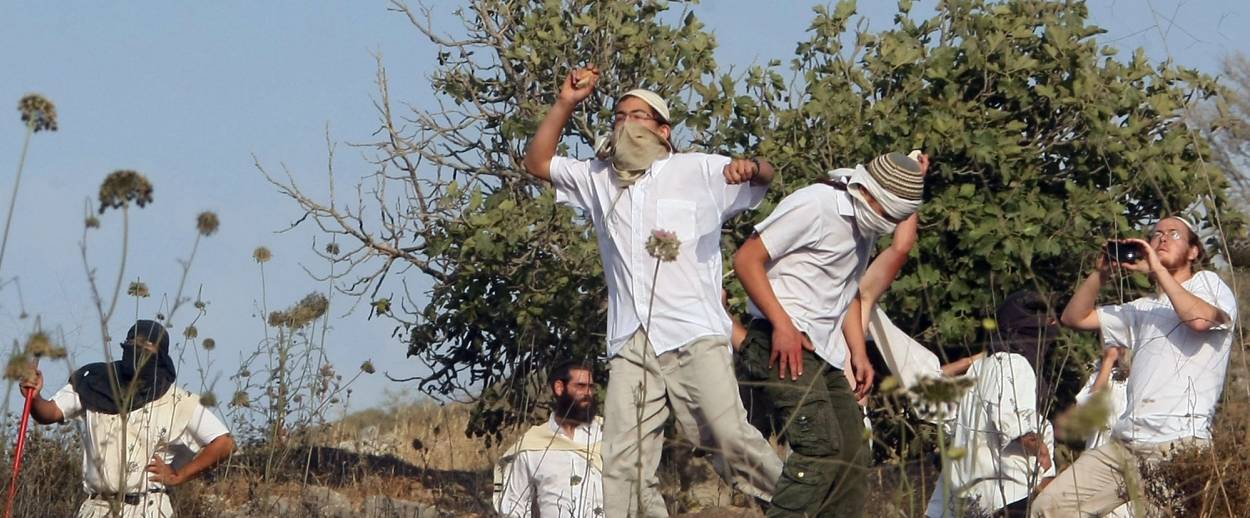

Although now shunned by Rabbi Ginsburgh himself, his pupils started and continue to carry out “Price Tag” terrorism, or as they called it initially, “Mutual Responsibility,” or Arvut Hadadit in Hebrew. They burn Palestinian fields or mosques out of revenge for terror attacks, or just for spite. Outlaws attacked IDF vehicles to disrupt state-mandated evacuations of illegally built communities and to deter Israeli forces from policing Jewish terrorists on hilltops.

A few of them took it one step further. A key figure here is Meir Ettinger, a grandson of Rabbi Meir Kahane, who has been in administrative detention by the State of Israel for six months, and who is a disciple of Rabbi Ginsburgh. He was even once a member of Rabbi Ginsburgh’s “Derech Chayim” movement, but abandoned it for its non-violent approach and adopted the “rebellion manifesto,” which called for violent acts in order to shake the foundations of the State of Israel.

Another player in this scene is Rabbi Shmuel Tal, whose disciples are probably not in the core of the violent group, but who share the same hatred toward the State and its establishment. Rabbi Tal changed his view regarding the State of Israel during the disengagement from Gaza Strip, saying that it’s no longer a part of the Redemption process but it disrupts it. One of Rabbi Tal’s students published a manifesto after the alleged torture of suspects in the Duma murders, stating that the Shin Bet is doing this because it is afraid of these young men, who intend to establish what they see as a real Jewish state in place of the current corrupted one. Rabbi Tal himself, like Rabbi Ginsburgh, does not encourage violent acts and in fact preaches against them, focusing on building alternatives to the secular institutes of the state instead. Nevertheless, understanding these rabbis’ philosophy is crucial to understanding the few who do not follow their pragmatic non-violent line.

The main characteristics of these different perceptions of sovereignty are the same: longing to go “back to the roots” and resenting the current State of Israel. This view is also shared by many ultra-Orthodox, or Haredi, people in Israel, but with one crucial difference: Whereas the ultra-Orthodox do not believe that the Jewish people is in the middle of a positive ongoing process of geula (national redemption), the rabbis behind the Hilltop Youth do—and also believe, significantly, that it is a religious duty to “act with God” and help advance geula by earthly acts, not just by committing good deeds and waiting for the Messiah to come.

Combining the two ideas—that we should help the process of geula and that the State of Israel is not a part of that process, but rather an enemy—can be very volatile. The good news here is that unlike ISIS, we are dealing here with a very small group—not tens of thousands of enthusiasts, but a few activists and a few hundred supporters. But the main rabbinic authorities have no influence on them, since their theological understanding of the role of the Israeli State is so radically different. And as the history of ISIS shows, fevered doctrines that preach a literal return to an ancient and glorious past do not seem to strike their adherents as crazy.

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.